The universal antidote

Part of a series of short Bodhisattva's Breakfast Corner talks on Langri Tangpa's Eight Verses of Thought Transformation.

- Antidotes to each of the afflictions

- The realization of emptiness as the universal antidote

- The importance of having the complete correct view

To continue with verse 8.

Without these practices being defiled by the stains of the eight worldly concerns

And by perceiving all phenomena as illusory

I will practice, without grasping, to release all beings

From the bondage of the disturbing, unsubdued mind and karma.

To keep these practices from being defiled by the stains of the eight worldly concerns we need a very powerful antidote.

There are two kinds of antidotes. There’s the one that we apply individually to different afflictions, like meditating on impermanence to counteract attachment; meditating on love or fortitude to counteract anger. And then there’s the one universal antidote that’s going to smash all of the afflictions, and that one is the realization of emptiness. That’s what this verse is bringing us into.

If we have the realization of emptiness, it counteracts all of the afflictions, and once the afflictions have keeled over and died, then the eight worldly concerns, they have no juice, because they’re the afflictions.

The first line is really indirectly hinting at realizing emptiness. When we realize emptiness, we’re understanding that things do not exist inherently, with their own self-instituting nature. We’re not saying that things are totally non-existent. This is quite important. What’s being negated is a certain kind of existence, not all existence.

When you’ve negated the kind of existence that has never existed, and will never exist, but which we believe in–inherent, or true, existence–then there’s still something left over, there’s still conventional existence left over.

In the case of the bodhisattvas, when they arise from their meditative equipoise on emptiness, these conventionalities still appear to them, but they appear differently to them than the way the conventionalities appear to us who still have very gross ignorance and self-grasping. They appear to these arya bodhisattvas as like illusions. Not AS illusions. But LIKE illusions.

There’s a difference between AS illusions and LIKE illusions. Illusions are things that appear one way but exist in another way. And when they appear, it’s very easy for them to trick us if we don’t know what they are. When we were babies and we looked in the mirror, we thought there was another baby in the mirror. We wanted to play with it. When you are riding on a ride in Disneyland, you come out of this ride (this was many decades ago, I don’t know if it’s the same), and you look across and there’s a reflection of yourself, and you see yourself sitting next to a ghost. The Haunted House. It appears like a real ghost. If you don’t know, you could think “Oh,” and look to see if there’s a ghost sitting next to you. Until you look and see there’s not a ghost.

But there are many things like that, where they appear one way and they exist in another way. We see them all the time. When we look on TV screens, we intellectually know that there are no people in the screen, but we relate to that screen as if there were real people in it. We get emotional, we scream at the screen. We say things to the people in the screen. There are no people there. But there’s the appearance of people.

In the same way, there is no inherently existent phenomena, but there’s the appearance of them. So in that way they are like illusions, because they appear one way, but they don’t exist in the way they appear.

It’s important when we negate inherent existence, to have the complete understanding, to have the complete correct view. It’s not sufficient just to realize emptiness. We have to be able to posit conventional existence afterwards and to see things as being like illusions after we come out of our meditative equipoise. Because if you don’t do that, then you’re essentially either going to say that your realization of emptiness made everything non-existent (so you can’t see anything when you come out of your equipoise), or you’re going to say “Well that was a nice trip, but actually things still inherently exist, because that’s the way they’re appearing to me and I believe that appearance.”

You have to adjust on both sides–learn to see the ultimate nature correctly and learn to see the conventional nature correctly. We need to do both of these for the correct view.

When it says, “And by perceiving all phenomena as illusory,” what we’re doing is we’re recognizing that they lack inherent existence, but they appear to be like that, but we don’t believe the appearance. That’s the way conventionalities exist. Things exist, but not inherently.

We still have to establish that conventionality. That’s quite important. Because if we don’t establish the conventionalities, then how are we going to practice, without grasping, to release all beings from the bondage of the disturbing unsubdued mind and karma, because we’ll say, “There are no sentient beings.” If we can’t establish conventionality, then you realize emptiness, you think emptiness means nothing exists, so then there are no sentient beings to have bodhicitta for. Then you’re going, “Why did I cultivate bodhicitta if there are no sentient beings? And there’s no enlightenment. And there’s not even me.” That’s why it’s so important to have the correct view of both of the truths, not just one.

Coming out of that meditation on equipoise, then perceiving sentient beings as illusory. Also perceiving their suffering as illusory. Again, that doesn’t mean that their dukkha doesn’t exist. It doesn’t mean that you look at sentient beings who are hungry and say, “Oh, that’s all just in your mind.” Or sentient beings who are sick, and say, “Well, you don’t exist,” or “Your sickness doesn’t exist.”

Those things exist, but the way you look at them, they don’t have the same charge as they used to. When we’re able to look at our own suffering, then it doesn’t have the same charge. When we look at other sentient beings’ suffering, we don’t panic and go crazy and get depressed, because we see that it’s like an illusion. We take it seriously, because it exists, but it’s like an illusion, and we can think if all those sentient beings could only see that their dukkha is like an illusion, they wouldn’t suffer so much from these different circumstances that they experience.

You begin to see that sentient beings’ suffering isn’t a given, it doesn’t have to be. It’s something that’s dependent on causes and conditions. The causes can be eradicated. Sentient beings can stop their dukkha and come out of that whole thing. So then you’re able to practice without grasping at inherently existent sentient beings, or inherently existent dukkha. Yourself not grasping. To lead these illusory-like sentient beings–that do exist–to liberation. That’s “to release them from the bondage of the disturbing unsubdued mind and karma.”

The disturbing, unsubdued mind is referring to the afflictions, the chief of which is ignorance. And karma, which is the actual thing that throws us into the next rebirth and causes the different experiences that we see.

Afflictions and karma are the second of the four truths, the true origin. We’re able to help sentient beings see the truth of nirvana by developing the true path in their mind, and in that way overcome true dukkha and true origins.

And seeing that all four of those truths are empty of inherent existence, and yet exist on the conventional level.

They say this is quite difficult. It’s easy to talk about. Oh yes, on the ultimate level they’re empty of inherent existence. On the conventional level they exist. It is very difficult to realize this. Because every time we say on the conventional level they exist, we go right back to grasping true existence. Because that’s what we’re so familiar with. It takes a while, really, to get to the correct view. His Holiness says that the correct view is difficult to understand, but once you understand it, then meditating on it and familiarizing yourself with it takes a long time, but doesn’t take that long compared to bodhicitta, which is very easy to understand, but very difficult to actually meditate on and transform the mind into that.

This was written by Langri Tampa, and it’s called The Eight Verses of Thought Transformation. Very good for us to practice this. There’s a lot in it.

Especially when you have problems. Instead of just throwing your hands up, “What do I do? I want to clobber that person!” Sit down and read this text. There’s going to be an answer in here for you if you sit down and read it. Or read the 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas. You’ll find answers in there for what to do. But if we just listen to the teachings and then when we have a problem just throw up our hands because we don’t know what to do, then we haven’t really taken the teachings into our own mind. We haven’t studied them after we’ve heard them. We write them in the notebook, put the notebook on the shelf, and don’t look at it again. And you have stacks of notebooks going up. But you never look at them again. So you don’t really think about them and apply them to your life, or meditate on them and transform your mind. It’s very important to do this. Just hearing the teachings is not sufficient. And nobody else can do the practice for us. We have to do it ourselves. You can hire somebody to do your laundry or do your dishes or mow the grass or plant the trees. But we can’t hire somebody to practice for us.

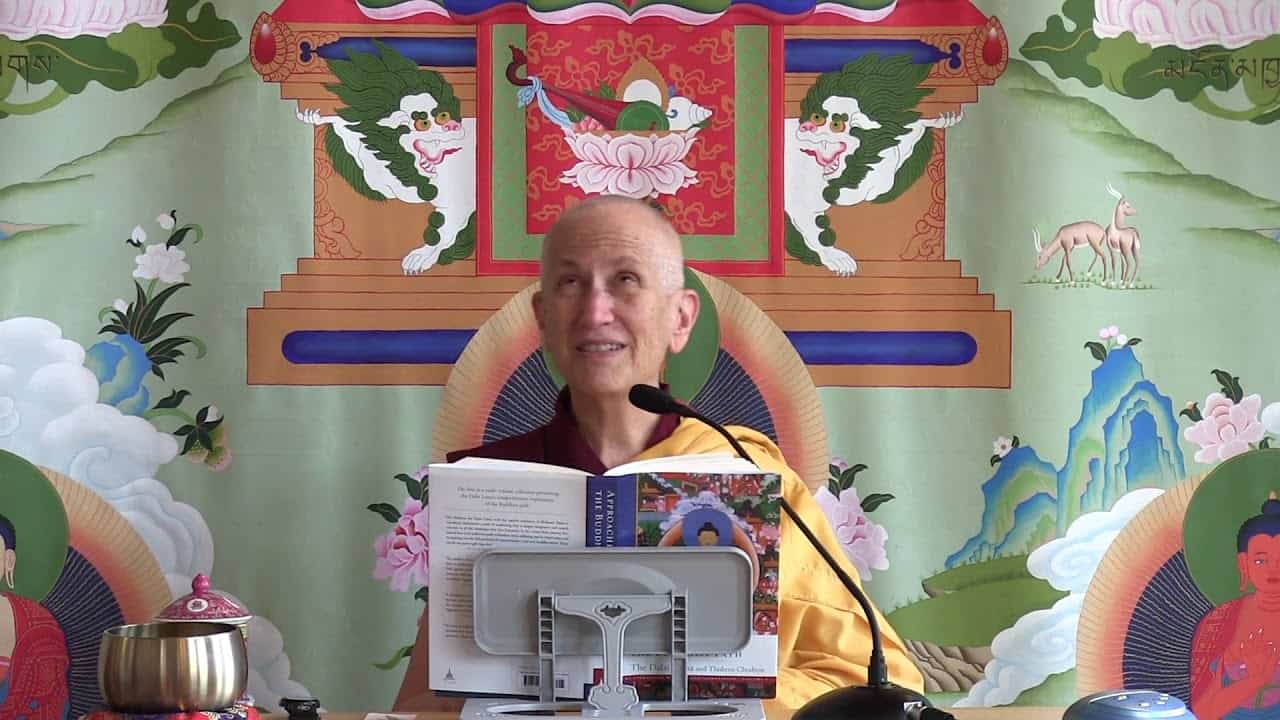

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.