Attachment endangers us

Part of a series of short Bodhisattva's Breakfast Corner talks on Langri Tangpa's Eight Verses of Thought Transformation.

- The importance of noticing the disturbing attitudes when they arise

- Realizing that the afflictions endanger ourselves and others

- Recognizing attachment as an affliction, even though it feels good

In all actions I will examine my mind

And the moment a disturbing attitude arises

Endangering myself and others

I will firmly confront and avert it.

One thing that’s important with this verse is to notice the disturbing attitudes. Lots of times they come in our mind, we don’t even notice them, they seem normal, and we just act them out. That is due to a lack of mindfulness and introspective awareness.

There’s another element here. When it says “endangering myself and others….” Another problem we have with remedying our afflictions is we don’t realize they endanger ourselves and others. So they arise in our mind, and even if we notice them, we don’t discern them as afflictions, we don’t discern them as harmful. We think that they’re beneficial and should be cultivated instead.

For example, when we have attachment in our mind—to someone or something—we feel happy, we feel close to that individual. It meets a need that we have for friendship, or for connection, or whatever it is. Even though it’s attachment, we don’t recognize it as attachment. Or even if we may say, “Well, I might be a little bit attached to this person,” we don’t think of it as anything harmful, because we feel happy. We’re connecting to somebody else, and what’s wrong with that, we always say.

There’s nothing wrong with being happy and connecting to other people. It’s the attachment to doing that that creates the problem. We’re social creatures, we have friends, we connect with people, we communicate. That brings a sense of happiness. Great. The attachment is when: “That person is really special to me, and I really want to be in touch with him. And I don’t want to jeopardize the relationship, and I don’t want to separate from him. It really meets some deep need in me and there’s no other way to meet that need except through this relationship.”

Are you seeing the difference between just enjoying the connection (and that’s it) and the attachment to the person, to the pleasant sensation. There’s a lot of it, too: “I’m important to somebody. And if I’m important to somebody, then my life is worthwhile, then it’s a good thing for me to be here.”

The attachment is very sneaky. It meets all those deep-seated things that we could say are normal human needs, but that we get attached to the feeling, or the person, or the situation that meets those (needs).

It really takes some discernment in our own mind to notice this.

There’s a practice (or a poem) from the Kadampa tradition called “The Ten Innermost Jewels of the Kadampa Tradition.” I spent some time meditating on these. It was extremely valuable because it really hits at all that sneaky kind of attachment

Maybe after we finish this poem (if we ever do) then I’ll do that,1 because it really emphasises the level of renunciation we should aim for. We’re not going to have it initially, but that we should aim for. It talks about going off where nobody knows you and living alone. And while you’re living alone, you’re not thinking about everybody you left behind and missing them. You’re not thinking about everybody down in town and how much they’re going to admire you for going off alone, and respect you, and how much they might write you letters of gratitude, and give you bags of tsampa or chocolate. You’re not thinking about any of that. You’re mind is completely in the Dharma. And it goes on and on and on. I won’t tell you the whole poem now. But it really hits at a lot of this kind of very sneaky attachment. The attachment to “I’m important to somebody. I’m needed. And wanted. I’m valued. I’m special.”

And it could be said to be a regular human need. But also, it’s a regular human need of ordinary people. I don’t think bodhisattvas get into that too much. Because a bodhisattva’s attention is focused on others, not on self. And bodhisattvas don’t need others’ admiration, or thanks, or whatever.

It’s also very interesting to watch what it is about those relationships. In Tibetan culture you become close to somebody else by helping each other with practical issues. In the West, that’s not how you become close to people. You become close by sharing your emotions. By sharing your inner secrets. That becomes the currency that makes people feel close to each other. Not going and painting a house together, or vacuuming the floor together. We get it through an emotional exchange. It’s quite different in different cultures. Very different that way. And I think it’s different in different historical times as well. For our great-grandparents, they had no time to share emotions and become close that way. They were just trying to stay alive. For them, even though it was in our culture, the thing that brought people close was helping each other out in practical elements. But it’s different now.

The point here is to really look inside and see those things. Not just to see them, but to ask ourselves, “Well, how is that harmful? How is being special in somebody else’s eyes, how is being that person’s closest friend, how is that harmful to me? Or to them?” This is something we really need to look at, because initially it doesn’t seem harmful. In a worldly way, it’s not considered harmful. In a Dharma way, that’s where the disadvantage comes in, because the attachment to somebody else, the attachment to feeling special and needed, becomes something that binds us to samsara.When they talk about the sixteen attributes of the four truths, under true cause—of course the foremost true cause of samsara is ignorance—but what is the example that is used in the sixteen attributes? Craving. It’s that kind of craving that keeps us bound to samsara.

It’s also that kind of craving that is a setup for pain. Because as soon as we’re close to people or objects, any two things that are close must separate. They’re either going to separate because something breaks, somebody dies, the friendship ends, you quarrel, or somebody goes off and has another best friend, or you get bored. But two things that come together are going to have to separate. And when we become very attached in this way it’s a direct setup for pain. For sure. 100% promised. Unless you’re the one who breaks up the relationship, in which case you feel okay, but the other person feels rotten. But then you don’t feel so good either because you blame yourself, “Oh they feel sad, I’m to blame, maybe I should go back together with him, then he’ll feel better.” We want to comfort him, even though we’re the one who broke up with them. Are we the person to comfort somebody whom we’re trying to distance ourselves from? No, we’re not the right person to comfort them.

You can see how this kind of craving and stickiness…. Craving feels so intense. Just think “sticky.” The mind is sticky. And that just creates, whenever there’s stickiness, you get stuck.

Then of course everything comes up: What do I have to do so that person is always happy? Oh, they’re becoming close to somebody else, I’m not the special one. Now I’m close to many other people, I don’t need them so much anymore. I feel guilty….

All this kind of stuff.

It’s something to really be aware of as practitioners, as people who are really interested in liberation and awakening.

For people who that’s not their aim in this life, maybe they’re practicing the Dharma because they just want to be happier, then this is not so important. But they will definitely experience pain. And that should make us wake up, too.

Not okay. I want the world to be different. I want attachment to always be fun, with no drawbacks, because attachment makes me feel so good.

Really check up if attachment makes you feel good. If attachment made the Buddha feel good, he would never have left the palace. He would have hung out with his wife and all those dancing girls and his son. He would have said, “Oh, all the people of the kingdom love me, I feel needed, I can do so much good.” Where would we be?

Audience: At the UU we’ve been talking about how you need to cultivate equanimity as the foundation of love and compassion, as the antidotes to anger. And then someone from the group came up for Sharing the Dharma Day, and he sat next to me at lunch, and he asked, “I’m having trouble with equanimity, because where does my wife fit into this picture? She has a special place in my heart, we’ve been married forty-something years. Are you telling me I should treat her like any other woman?” He was genuinely very troubled about this. So I’m quite curious what perspective you would share.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: There’s a difference between feeling equanimity and acting the same way. Clearly, you don’t treat your wife like any other woman. The thing is, reduce the attachment and replace it with equanimity, but that doesn’t mean you treat everybody the same way. You don’t treat somebody who’s two years old the same way you treat someone who’s thirty. We treat somebody we know well differently than we treat a stranger. We still have to deal with social habits and these kinds of things. But the idea is that rather than favoring some people and distancing ourselves from others—feeling close, feeling distant—we develop a feeling of equanimity and closeness with everybody. But it’s not the closeness that’s the sticky closeness. That’s the trick.

A brief discussion can be found here ↩

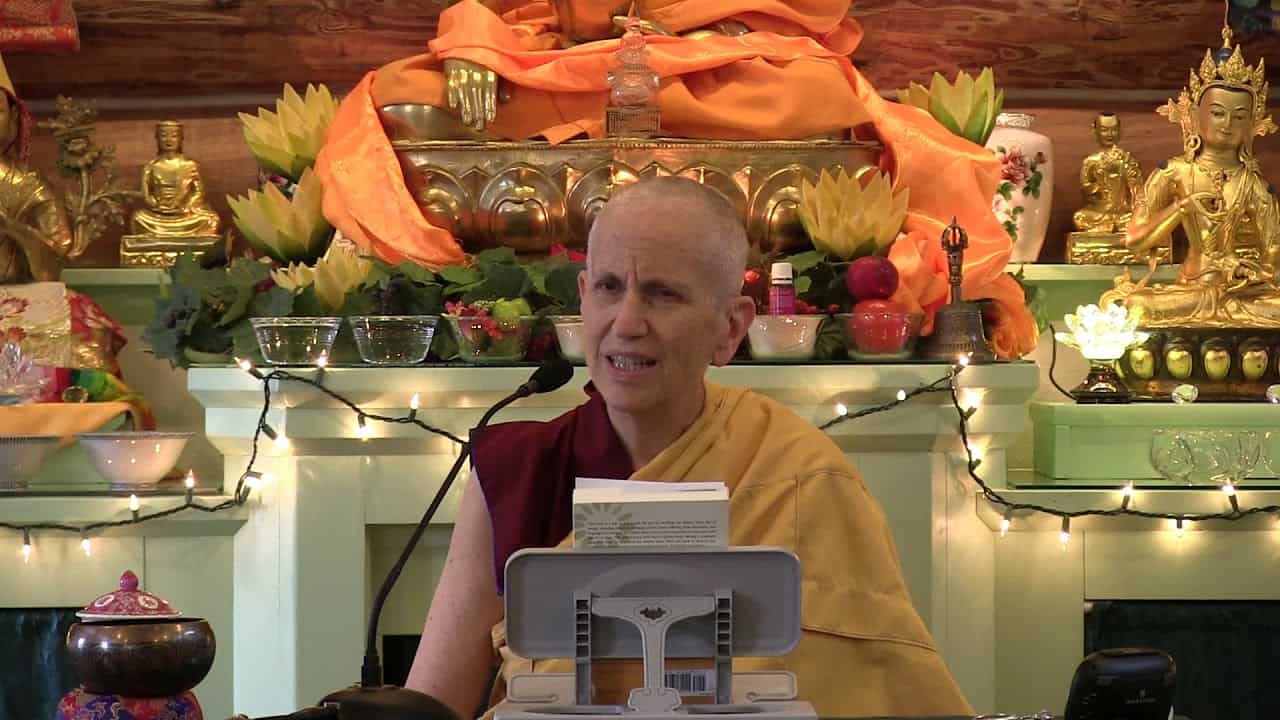

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.