Taking-and-giving meditation

The text now turns to relying on the method for happiness in future lives. Part of a series of teachings on the Gomchen Lamrim by Gomchen Ngawang Drakpa. Visit Gomchen Lamrim Study Guide for a full list of contemplation points for the series.

- The difference between self-centered thought and self-grasping ignorance

- How to meditate on the teachings

- Learning to identify our negative mental states and the antidotes needed to overcome them

- General outline for the taking-and-giving meditation

Gomchen Lamrim 77: Taking-and-giving meditation(download)

Contemplation points

- Start with yourself.

- Imagine the dukkha you might experience tomorrow (dukkha of pain, dukkha of change, and the pervasive dukkha of conditioning).

- Once you have a feel for it, take it on your present self so that the person you are tomorrow doesn’t have to experience it. You can imagine the dukkha leaving your future self in the form of pollution or black light, or whatever is useful to you.

- As you take on the dukkha in the form of pollution/black light, imagine it strikes at the self-centeredness at your own heart, like a thunderbolt, completely demolishing it (self-centeredness can appear as a black lump or dirt, etc).

- Now think about your future self next month. You’re future self as an old person and do the same exercise…

- Then consider the dukkha of those you are close to using the same points as above.

- Next, consider the dukkha of those towards whom you feel neutral.

- Next, the dukkha of those you don’t like or trust.

- Finally, consider the dukkha of beings in all the different realms (hell, preta, animal, human, demi god, and god).

- Having destroyed your own self-centeredness, you have a nice open space at your heart. From there, with love, imagine transforming, multiplying, and giving your body, possessions, and merit to these beings. Imagine them being satisfied and happy. Think that they have all the circumstances conducive to attaining awakening. Rejoice that you’ve been able to bring this about.

- Conclusion: Feel you are strong enough to take on others’ dukkha and give them your happiness. Rejoice that you can imagine doing this, practice it as you notice and experience suffering in your daily life, and offer prayers of aspiration to be able to actually do this.

Transcript

Good evening. Let’s start with our motivation and bring our mind to what our task is at this present moment. What are we supposed to be doing right now? What do we have the privilege and benefit of doing right now? Let’s bring our mind to that. We’re not thinking about what just happened, or what we want to do, or worrying about something else.

We’re paying attention to what our task is at this present moment, which is generating bodhicitta so that we can have a very expansive, extensive, noble motivation for listening to the teachings. And then we’re actually listening to the teachings and thinking about them in such a way that we can remember them and integrate them into our lives. It’s not time for distraction. It’s not time for falling asleep.

I think this can be very helpful to us throughout the day at any particular time, to check in and ask ourselves if we’re doing what needs to be done at this particular moment. With a mind reaching out to each and every living being, wanting to benefit them, to repay their kindness and to lead them to the kind of happiness that will really fulfill them, we cultivate our motivation and listen to the gomchen lamrim.

Self-grasping ignorance

There were some questions that came from our Singaporean friends that I wanted to address first of all. One of the questions they wrote, a very good question that comes up a lot, is, “What’s the difference between the self-centeredness and the self-grasping ignorance?” We kind of covered this a little bit last week, but it’s helpful to go over it again. Self-grasping ignorance is the ignorance that grasps ourselves and all phenomena as inherently existent. It’s the root of samsara, and it’s what has to be eradicated in order to attain liberation and of course to attain full awakening as well.

The antidote to the self-grasping ignorance is the wisdom that realizes emptiness. Here “self” can mean the person, so grasping the person as inherently existent, and sometimes self means inherent existence. Self-grasping ignorance becomes the ignorance grasping at inherent existence. The word self has two very different meanings. You have to figure out what it means in any particular situation. But this is an afflictive obscuration that is counteracted by wisdom and needs to be eliminated to attain either liberation or full awakening.

Self-centered mind

The self-centered mind, technically speaking, is the mind that cherishes our own liberation rather than other beings’ liberation, or more than other beings’ liberation. This is a mind that says, “I want to attain nirvana, but for myself alone. I don’t want to do the extra work that it takes to become a buddha for the benefit of sentient beings.”

This mind is counteracted by love and compassion and bodhicitta. It’s not counteracted by the wisdom realizing emptiness. And the self-centered thought is not an afflictive obscuration. You can attain liberation having that self-centered thought. That’s what the arhats have, so it’s unlike the self-grasping ignorance that’s the root of samsara and needs to be eliminated to attain liberation. But to attain full awakening, the self-centered thought definitely needs to be eliminated, because we can’t become a buddha without having the bodhicitta mind, and the bodhicitta mind is the direct counterforce to the self-centered mind.

Sometimes when we talk about self-centeredness in a very, very general way, then we include in it all of our attachment, and our anger, and all the craziness in our mind that causes us to create negative karma and keeps us in samsara. That isn’t the technical meaning of self-centeredness, but often we include everything in that because when we look at our actions created under the influence of the afflictions, they all have that self-centered backing of, “My happiness is the most important and take care of me first.” Me first. Remind you of something? We certainly need to overcome both of those minds to attain buddhahood, but they’re quite different minds, quite different states of mind.

Resources for meditation

Then the second question asked was for resources for meditation on the different themes, meditations that correspond to the teachings that we’re getting. I would recommend the “Easy Path” that we did right before this text. It was written as if it were a meditation manual, and so it has a whole paragraph or two paragraphs that you can recite and then you contemplate along with what that paragraph describes. That’s a very good way to do the meditations on these different things.

Also, if you get the book Guided Meditations on the Stages of the Path, there’s a lamrim meditation guideline with the basic meditations and all the meditation points under them in it. It’s also on the website. And in the book Guided Meditations on the Stages of the Path there’s also a CD with me leading the meditations, and for people who no longer have machines that take CDs, it’ll tell you where to download it on your tablet or iPod or whatever from the web.

What you really want to get in the habit of doing is learning how to read a passage in a book, and then from it making your own meditation outline. If whatever topic you’re reading about is well-written, then each paragraph should have either a topic sentence or a concluding sentence, or something like that, so that you should be able to pick out the important points that are following in a sequence that help you develop a certain thought.

It’s helpful to learn how to pick those points out of a passage you read, and just write them down so that you know the points to contemplate. That’s very, very helpful because it teaches you to pay attention to what you’re reading. It helps you pick out the important points, and then when you meditate, you’re able to stay on track because you’ve read something that’s an elaborate explanation, but you have the main points written down, so you remember the elaborate explanation and you contemplate that while you’re meditating on the main points.

And then, as always, it’s very helpful to make examples of the main points you’re meditating on, and from your own life, or from what you’ve seen around you. In other words, make that teaching something very personal to yourself. We’re not just contemplating dry facts or abstract principles. We’re applying them to what we’ve witnessed and experienced in life and checking to see if they’re true or not. And we’re also checking to see if we change the way we’re thinking according to those different points, or see the situation according to the different points, to see if that helps us loosen our afflicted mental states. So, you kind of try those things out, and try working with them yourself.

Group meditation on the self-centered mind

For the last two weeks, we’ve gone through a lot about the self-centered mind, and the benefits of cherishing others. So, write a list of all the disadvantages of the self-centered mind, and then look in your own life. “Self-centered mind: you’re a thief, you steal my virtue.” Well, is that true? When I’m self-centered, am I able to create virtue? Well, no, but why not? What are some examples of how my self-centeredness prevented me from creating virtue? What are some examples?

Audience: [inaudible]

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): No, I want specific, in your life examples. We’re doing a group meditation now. This is exactly how you do it when you’re doing it individually. The first point is that self-centeredness prevents me from creating virtue. So, how? You ask yourself, “How in my life has self-centeredness prevented me from creating virtue?” What are some examples?

Audience: Being asked to help out with friends or at the Dharma center, and having my own plans, and choosing to do that instead because of valuing my own plans more than helping others.

VTC: Okay, that’s a good example. What’s another example?

Audience: Being preoccupied with the outcome that I wanted, and then speaking harshly to someone who I was perceiving as getting in my way.

VTC: Yes, another good example. Self-centeredness: what’s another disadvantage of it?

Audience: Small incidences in my life that are trivial, making huge dramas out of them where I’m the center of the universe.

VTC: Okay, good. So, that’s a disadvantage. What are some personal examples of that?

Audience: Having feelings of guilt afterwards.

VTC: Okay, so you felt guilt after something you did, or something you didn’t do.

Audience: Yes, I rolled the microphone yesterday on the floor, and today I got a favor, so I’m feeling pretty guilty right now. [laughter]

Audience: Being upset about something somebody did, thinking that they did it to be disrespectful or make me angry, when they probably didn’t notice me at all, or notice that I was upset about it.

VTC: Okay, so that’s another good example—making mountains out of molehills. Do you see what I’m getting at? How to do the meditation? This is just an example. We’re not going to do the whole meditation.

Then, the benefits of cherishing others: what’s one benefit of cherishing others? Okay, you create lots of merit. What are some examples, personal examples, of how you can create merit by cherishing others? What’s something that you want to put into practice, that you want to do.

Audience: When somebody is sick, taking care of them, bringing them food and helping them out.

VTC: Okay, good. Do you see what I’m getting at? We don’t want just general ideas. We want specific things, because that will make the meditation very rich, and will show you exactly what you can do to put the meditation into practice. What’s another benefit of cherishing others?

Audience: We can rejoice in their welfare, and when good things happen to them, and we then have joy that we wouldn’t have had.

VTC: So, we can feel happy when good things come to them, when good things happen to others. That’s a benefit. What are some instances where you can do that?

Audience: You see someone being praised.

VTC: Not someone. I want to hear specifics. When I see so and so do this and that.

Audience: Helping someone to learn English, and then they go and apply for a driver’s license.

VTC: Yes, very good.

Audience: Venerable Jampa asked the community to go to Hong Kong, and the community said, “Yes, go, it’s a good experience.” And that’s a way to rejoice. That something that we knew would be helpful and beneficial.

VTC: Right. Are you getting what I’m saying? If you leave your example with helping somebody when they need help, that won’t wake you up so that you help somebody when they need help. But when you give yourself specific things that you can do to help, then it gives you some momentum there. Of course, you can see when other opportunities come to help. Do you get what I’m saying about the specific things that really make the meditation very tasty for you? For example, if we’re doing the analytical meditation on the disadvantages of cyclic existence, one of the disadvantages is that there’s no satisfaction. So, what are some examples that you can make from your own life experience that illustrate that there’s no satisfaction in cyclic existence?

Audience: I would say trying to set my dream job, my dream career, with my best friend, and setting up a practice and putting all my energy and time into it, and it didn’t really work.

VTC: That’s a very clear example. What’s another example of things being unsatisfactory in samsara.

Audience: Six chocolate chip cookies. [laughter]

VTC: Yes, and a stomachache.

Audience: And a stomachache.

VTC: But also look a little deeper than the chocolate chip cookies. Are there things that you’ve really wanted, that when you’ve gotten them have left you feeling dissatisfied at the end?

Audience: Going to a different country, thinking that it’s going to be better, and then getting a degree thinking that everything is going to be better after that. Then getting a real job, thinking everything is going to be better after that. Getting a stable relationship, thinking everything is going to be better after that. Breaking off, getting an apartment for myself, thinking everything is going to be better after that. Thinking, “I’m going to attain single-pointed concentration in three months,” and thinking everything is going to be better after that. [laughter]

VTC: Good examples!

Audience: But things might be better after the one-month retreat. [laughter]

VTC: Let’s wish him well, okay. This is an example of how to do it when you’re in silent meditation yourself. Here we were passing the microphone and doing it, but I wanted to make sure you have the idea of what you’re supposed to be doing.

Audience: So, for the act of cherishing others, someone says, “In a long line at the grocery store, let someone else go in front of you. Or get a warm cup of coffee for someone standing outside in the cold, who has no money.” And someone said for rejoicing, they’re rejoicing in those who are at the Abbey for winter retreat: “I want to be there but can’t, so I’m rejoicing that others are there.” And other people went, “Yes!” [laughter]

VTC: Okay, very good.

This explanation in Transforming Adversity of how to do the taking-and-giving meditation is the best that I’ve ever encountered. It’s the most detailed one that I’ve encountered, so I really recommend it. If you look on the website, there’s a description, and there’s a couple of articles written on how to do it, but this one in Transforming Adversity into Joy and Courage is very, very thorough in the explanation.

This meditation actually has a root in one of the sutras that is called (inaudible), so it’s a biography of somebody. In that sutra, the Buddha taught about taking on the suffering of sentient beings and giving them your happiness. Also in Precious Garland, in a verse in the fifth chapter, one of the lines reads, “May all negativities ripen upon me, and may all my happiness and virtue ripen upon other sentient beings.” So, that is seen as a root. Actually, for the equalizing and exchanging self with others practice, which culminates in taking and giving, and also Shantideva in Engaging in the Bodhisattva’s Deeds, says that if we don’t exchange self and others, taking on the suffering of others and giving them our happiness, we won’t become a Buddha. But if we do, then attaining full awakening is definitely possible.

That makes it pretty necessary to do, doesn’t it? But this meditation does not suit everybody necessarily where they’re at right now, so if this meditation doesn’t feel comfortable to you, there’s no push to do it. You have to do it when it feels comfortable, when it’s meaningful to you. Because what we’re imagining doing here is taking on the suffering of others with a feeling of great compassion, kind of saying, “I’m going to bear their pain and misery and the three kinds of dukkha so that they can be free of that. And then I want to transform and multiply my bodies, possessions and merit, and give that to all other beings so that they can have their temporal needs in samsara fulfilled, as well as their ultimate needs with their long term spiritual realizations fulfilled.”

Audience: Did the Buddha encourage everyone to be a bodhisattva, and if he didn’t, why not?

VTC: I think because the Buddha was able to see people’s individual dispositions and interests and tendencies, he taught them according to those. In the long term, he wanted everybody to become a Buddha, which means becoming a bodhisattva first, but in the short term, if he saw that some people weren’t ready for that then he taught them what they were ready for, what was meaningful to them and how to attain their personal liberation from samsara.

This gets into the discussion of, “Is there one final vehicle or three final vehicles?” Some systems say there’s three, in other words, some people will follow the hearer vehicle, become an arhat, finished. Other people will follow the solitary realizer vehicle, become that kind of arhat, finished. Other people will follow the bodhisattva vehicle, become a Buddha, finished. So, there are three final vehicles in the sense that when you complete your vehicle, you’re done with what you’re doing. But then other schools, and these are usually the higher schools, say actually there’s one final vehicle. The Buddha wants everybody to attain full awakening. That’s the final goal, but because not everybody’s initially ready to enter the bodhisattva path, he teaches them whatever they’re ready to hear and places them in whatever vehicle is most conducive for them at that particular time in their spiritual development.

Audience: So, it’s like the strength of his compassion? He really just wants to benefit people. He’s not going to say this is the one right way. He’s just going to help people in the most pragmatic way?

VTC: In the long term, this is the best thing you can do, but in the short term, do this. It’s kind of like you have a few little kids in your back seat, and you’re driving from here to New York. It’s a long drive. There’s one kid who’s really focused on, “I want to see the Statue of Liberty.” All they have in their mind is Statue of Liberty, Statue of Liberty, Statue of Liberty. Every time you see something else on the way: “Yeah, that’s nice, but I want to see the Statue of Liberty.”

Then there’s another kid in the car that says, “You know, I can’t really relate to the Statue of Liberty, but I saw a picture of the Grand Canyon, and I want to go to the Grand Canyon. The Statue of Liberty is very far away. It’s so long to sit in the car, and I don’t like sitting in the car so long, and you can only count the number of license plates from each state for so long until you get totally bored. So, I just want to go to the Grand Canyon and see the Grand Canyon, and I’ll be happy.”

Mom and Dad want to go see the Statue of Liberty, too, but they have this kid that doesn’t want to drive across the country, so what do they do? They say, “Okay, we’re going to go see the Grand Canyon.” So, they go and see the Grand Canyon, and that’s very nice, and then they say, “Oh, but you know, there’s something even better than the Grand Canyon on the way to the Statue of Liberty. Let’s go there.” Maybe they don’t even mention the Statue of Liberty, but we can go to Ohio. What’s exciting in Ohio? Who’s from Ohio? We can go to Oklahoma. What can you see in Oklahoma? [laughter]

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: Okay, let’s choose something else, let’s skip Oklahoma. Michigan? Okay, the Great Lakes. Yeah, we can go to Michigan, and on the way, we can stop in Chicago. In Chicago you can see the loop and downtown Chicago, and you can see—what else is in Chicago? The hospital where I was born in. You can go see that hospital.

So then the kid who was just at the Grand Canyon says, “Well, yeah, I’d really like to see the hospital she was born in, you know? That’s kind of nice. And Lake Michigan, yeah, that’s good, I’ve heard they have good beaches on Lake Michigan. Okay, I’ll go there, but I’m not going to the Statue of Liberty. It’s too far.” But then you get them to Chicago. Do you see how you have to be skillful?

If at the very beginning, when you’re still in Newport, you say, “Shut up kid, we’re going to see the Statue of Liberty.” Then they’re going to be screaming the whole ride. You guide them in a skillful way to get them where they’re going, and you hold out a little carrot—kind of the next thing that they can get that’s going to make them happy on the way. So, it’s in that way that the Buddha wants to lead everybody to the final goal of Buddhahood. He has to do it very skillfully. I saw a cartoon once where there were the parents and the kids in the backseat, and there was the sign, “Nirvana straight ahead,” and the kids in the backseat are going, “Are we there yet?” [laughter] That’s kind of like us.

Let’s come back here. This meditation is done to really increase our love and compassion. We’ve just been doing the seven points cause and effect instruction, developing love and compassion, meditating on equalizing and exchanging self for others, so by now, our love and compassion should be strong—somewhat. Or stronger than it was before. The way to really develop it is to think of taking on others’ misery, others’ dukkha, with the feeling of compassion and giving them our happiness with the feeling of love.

Now, some people even before starting the meditation go, “I have enough suffering already. I don’t want to even think about taking on others.” And other people say, “Well, I can think about taking on others, but I hope the meditation doesn’t really work, because I don’t really want to take on others.” Both of these people, they’re stuck. The first one is just saying, “I have enough problems of my own, I don’t want to take on others. I have too little happiness myself. I don’t want to give away my body, possessions and merit.” What would you say to that person? What would you have them meditate on?

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: Kindness of others, yes. What else? Well, what are they missing? When they think like that, what are they lacking?

Audience: They could do disadvantages of their self-centered attitude.

VTC: What are they lacking—love and compassion, aren’t they? They’re saying, “I have enough suffering already, I don’t want more,” so they don’t have compassion, wanting to alleviate others’ suffering. And, “I have too little happiness myself; I don’t want to give it away,” so their love is low also. What do they need to meditate on? The seven points of cause and effect, and equalizing self and others, and the four immeasurables. Before starting this meditation, that person needs to go back and juice up their love and compassion.

Then for the person who says, “Okay, I’ll visualize it, but I hope it doesn’t really work,” what are you going to say to that person?

Audience: One day I was doing giving and taking, taking and giving, and it became clear in my heart that when I was taking, it was destroying the resistance, whatever walls were up, and the difficulties of opening the heart to others.

VTC: That, actually, is an example of the meditation working and doing what it’s supposed to do.

Audience: Yes. It became clear in my heart that it was helping my heart to open.

VTC: Exactly. So, the person who’s afraid of doing the meditation isn’t seeing the benefits of it. They have to think of the benefits of doing the meditation, and they also have to realize that this meditation is done in your imagination, and in actual fact, we cannot take on, for example, other’s suffering or others’ negative karma. Everybody creates their own karma, experiences their own karma, but just the process of imagining that and imagining giving away our body, possessions, and virtue, just that process has the salutary effect of what you were saying—of opening our own heart and releasing our own resistance.

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: Right. It could be the fear of loving, the fear of experiencing pain. Whatever kind of fear that is there, that is actually a form of self-centeredness. It’s important to realize that they can release that self-centeredness and do the meditation, and it’s going to have good effects on them if they do it sincerely.

Audience: I was wondering in that example where they don’t want to end up with the suffering, if you would have them think about fortitude and also about emptiness.

VTC: Yes, I think meditating on fortitude and emptiness, both of those things, would strengthen their mind so they can see that suffering is not going to destroy them. And actually, if they did a little bit of the four establishments of mindfulness—especially mindfulness of feelings where you meditate on painful, pleasant and neutral feelings—if they have a little bit of that, they’ll also come to see that those feelings are not going to destroy them, and those feelings are dependent; they arise from causes. They’re impermanent; they don’t last forever.

What I’m getting at by going into this is when you run into an obstacle in your mind, when you face some resistance to doing a meditation, stop and ask yourself, “What is it that I’m thinking or feeling that is the resistance, and what is the lamrim meditation or the lamrim topic that I need to contemplate to help me get through that and release that resistance?” We have to think about this, and in this way we learn to become a doctor to our own mind. That way, when we have a problem, we know how to meditate to solve our problem. We don’t just go there, and we’ve heard years and years of teachings, and now we’re angry at somebody, and we don’t know what to do.

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: Yes, come pounding on my door: “I’m angry. What do I do?” Well, I’ve been telling you what to do for the last seven years. No, longer. So, it’s important to develop this capability ourselves, to see what we need to meditate on, and to be a doctor to our own infantile, sick mind.

Audience: I was reading something by His Holiness, and it suggested doing this meditation, and I was in a really dark space in my life, and I didn’t want to do it. I thought, “I’ve got enough suffering,” just like you’re talking about. One day when I was sick in bed, I decided to do it anyway. Doing it anyway is what I needed. That’s how I saw the benefits of it immediately, kind of like Venerable Yeshe is saying. That seemed to be a great antidote to me, just to do it anyways. I realized that I wasn’t going to actually take someone’s suffering from them.

VTC: This is an interesting thing. Your mind’s putting up some resistance, but you say, “I’m just going to do it anyway.” It’s not shoulds, have-tos, supposed-tos, guilt, and it’s not, “I’m so afraid. I’m so frozen. I clearly can’t do it. It’s going to destroy me. What do I do? I’m freaking out…da da-da-da-da.” It’s like, “Okay, there’s some fear. There’s some resistance, but I’m just going to do it anyway and see what happens.” That’s a very nice approach, isn’t it? You’re not letting the self-centered mind put you in prison and overwhelm you. You’re just saying, “Okay, I have this problem, but let’s just do it anyway and see what happens.”

But it was kind of like me. When I was a little kid, I was an extremely picky eater. Very, very picky, and I did not like salad, and I did not like pizza. Those of you who know me well know I eat salad every day, and I love pizza, so there was some transformation that happened in the middle there, but for many years I just refused to eat salad and pizza. I guess at some point, I must have said, “Well, let’s eat them anyway.” And then I realized they were okay.

Sometimes just giving ourselves the chance to try something instead of having the forgone conclusion that I’m not going to like it, so I shouldn’t even try it is what makes the difference. But I remember as a kid, there were many things I just didn’t want to do. I did get invited to go here and there to do this and that, and: “I don’t want to. I don’t want to go ice skating, I’ll just fall down. I don’t want to go horseback riding, I’ll fall off.” This, that, the other thing: ”I don’t want to, I don’t want to.” And very often my parents made me. They’d say, “Go, you’ll enjoy it.” “No, I won’t.” I was kind of bratty.

They made me go, and it was amazing because I learned many things that I did enjoy. I didn’t always want to admit it to my parents afterwards, but the next time the opportunity came to do that thing, I said okay. It’s just that thing of, “Okay, let’s give myself a chance instead of getting stuck in a foregone conclusion that I’m not going to like it, it’s not going to work, it’s not for me.” But I’ve tried some of the foods that you know I don’t like. [laughter]

Let’s get back to what we’re doing here. Yes, our skits are a wonderful opportunity of, “I don’t want to, but let’s do it anyway.” When we’re practicing the taking part, we’re taking from two things: the sentient beings and their environment—maybe it’s better to say living beings and their environment. And then within living beings, we can take from ordinary sentient beings, bodhisattvas on the path of accumulation, the path of preparation, and we can also take from aryas. So, there’s different kinds of living beings. They’re all sentient beings, actually—anybody who isn’t a Buddha is a sentient being—so, we take from sentient beings and from their environment. Even within the ordinary sentient beings that haven’t entered a path, we have the beings of the six realms: the hell realms and the hungry ghost realms, animal and human realms, and demigod and god realms. We’re taking from all of those, and we’re taking from the environment that they inhabit.

There’s three things that we want to focus on taking from sentient beings. One is their dukkha, so the three kinds of dukkha: the dukkha of pain, the dukkha of change, and the pervasive dukkha of conditioning. We want to take those three from sentient beings, the three branches of dukkha. Then the second thing we want to take from sentient beings are the causes of that dukkha—in other words, the afflictive obscurations. And the third thing we take from them are the cognitive obscurations. Those are the three things.

Of course, when you’re really meditating, when you start out with the dukkha of pain, there’s lots of different examples with that. And the dukkha of change, there are many, many examples of that. I’m just giving you the outline, but within each one there’s many examples and many things to take. So, sometimes when you do the meditation, you make big categories like, “I’m taking from all sentient beings all of their dukkha.”

And sometimes you do the meditation, and you do it in a lot of detail, like taking from the beings in the cold hells the dukkha of their cold, and giving them all the heat and warmth I can, not just from a heater but from a kind heart, from a warm heart. When I think of cold hells, to me it goes very well with somebody who has a cold heart. In cold hells you can’t move; you’re frozen. When you have a cold heart, it’s the same way. In the hot hells you’re screaming all the time, kind of like somebody who has a really bad temper. They’re overheated with a bad temper. There’s parallels here; you can see them.

Now, they say that it’s very good to start with yourself when taking from sentient beings. So, instead of starting with the hell realm—because we don’t even want to think of the hell realm, so it’s going to be really difficult to imagine taking their suffering—we start with ourselves, and we start with very simple things. If you were doing the practice today, think of the kind of dukkha you could experience tomorrow. And then you imagine taking that dukkha upon yourself now out of compassion, so that you bear it, you experience it now, so that the person you’re going to be tomorrow is free of that suffering. What are some examples of the dukkha that you could be experiencing tomorrow?

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: Illness, rotten mood, sore knees, headache, cold, death, frozen toes, falling in the snow, people not happy about what I’m serving for lunch: you think of suffering you could experience tomorrow, and then you work up your courage, and you take that suffering upon yourself right now.

There we were just talking about the suffering of pain. What’s some of the dukkha of change that you might experience tomorrow? After you were told not to think of bad and good meditation sessions, maybe having a pleasant feeling in meditation and then staying on your cushion too long, so that your body started to hurt, and you didn’t want to go back for the next session—something like that. What other dukkha of change could you experience tomorrow? Enjoying shoveling snow for the first fifteen minutes and it doesn’t continue. What else? Eating too much. And then what about the third kind of dukkha? The pervasive dukkha of conditioning, what’s some of that you could experience tomorrow?

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: Yes, just being a human being that has karma that can ripen out of the blue, and things that you didn’t expect to happen could happen. Right. Creating karma under the influence of whatever we experience tomorrow, that’s certainly dukkha.

Audience: When you’re shoveling snow and you’re actually feeling good about it, but then you start wondering how long is that going to last, is that the suffering of change or the suffering of conditioning?

VTC: I would say you have a good feeling at the beginning, and then you bring doubt on yourself, so I would say it’s the second one. You’re shifting into a bad mood.

Audience: The suffering of conditionining—would you think of your obscurations or your afflictions?

VTC: Yes, just being a living being with obscurations and afflictions and seeds of karma that are going to ripen—just that is the pervasive dukkha of conditioning.

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: Yes, the third one encompasses the first two.

Taking on the suffering of others

So then you think of this and you imagine yourself, tomorrow’s self, and you imagine taking that suffering. And when you take that suffering, there’s different ways to imagine it. You can imagine it as pollution coming out of who you’re going to be tomorrow. You can imagine it as black light that comes out your right nostril, your future self’s right nostril that you inhale through your present self’s left nostril—if you want to get really detailed about nostrils and things like that. Or you can just imagine it as pollution that you inhale.

Then you think of your self-centeredness and your self-grasping. Again, there are different ways you can think of it. You can think of it as like a pile of dirt. You can think of it as a rock, as a bunch of dust, but something in the middle of your chest that you think is the physical representation of your self-centeredness and your self-grasping. Then as you take on the pollution, or you inhale this black light, you imagine that it strikes here at the rock or the lump or the pile or whatever it is and completely demolishes it. Some people don’t find that kind of visualization appealing, so they prefer maybe to think of it as a lot of dirt in your heart and you’re inhaling some kind of special cleaning agent—non-toxic, organic—that’s not going to poison you, but is going to remove all that dirt at your heart. You can adjust the visualization according to what suits you.

It’s actually a very skillful thing if you start with tomorrow’s self, which is in the continuum of who you are now but isn’t exactly the same person you are now. So, it’s easier to take from your future self, but what you’re doing is taking what your future self doesn’t want, and using it to destroy what your present self doesn’t want. You’re taking their dukkha to destroy your self-centeredness and self-grasping ignorance. It’s not that you just take on their suffering and then it just sits inside you and you get a stomach ache and the diseases you were afraid of getting—it’s not like that.

You take it on, but it gets transformed in a very healing way so that you are completely freed of the causes of your own dukkha. So, you start with tomorrow’s self, and then you think about next month’s self and the various dukkha you could experience then, and then you think about if you live to be an old person, the dukkha that you could experience then: your body hurting, people looking at you like you’re kind of old fashioned, or you’re not with it, being forgetful, knowing your days are limited. The dukkha of death, you know—are we ready to face our death and imagine taking on the suffering of dying upon ourselves? Even if it’s our own suffering of dying, do we have the fortitude inside to imagine that?

So, you do it with yourself for a while, and then you progress to people who are close to you, friends and relatives who you feel fond of. From there, you go to neutral beings. Ffter that, you go to people that you don’t trust or don’t like, or whatever. And then, finally, you do all the different realms of living beings. You can go through the different realms one by one thinking of the different kinds of dukkha those beings experience. You take that on yourself and use it to destroy your own self-centeredness and your own self-grasping ignorance.

So then you have an open space in your heart. Within that open fresh empty space in your heart, then you can, with love, imagine giving your body, your possessions, and your merit. There are lots of detailed explanations to come about how to do all these takings and givings, but I wanted to go over the basic meditation so that each time that I talk about the details, I’m not going to say, “Do this for yourself tomorrow, and then yourself next week and yourself the rest of life and then do it for friends and then strangers and then enemies and then all sentient beings in this realm and that realm.” It’s helpful just to have you remember all of that each time I go through the details. Similarly, It’s important to pay attention to how you visualize when you take it. You don’t just sit there with all their dukkha and the causes of their dukkha inside of you festering like rotten garbage. You use it to destroy your own self-centeredness, your own self-grasping ignorance that is that dirt or rock or whatever it is at your heart, and then from that empty space, you give your body, possessions, and merit, by transforming them.

That’s the basic outline before we go into the details. Are there any questions so far?

Audience: It talked about these different kinds of dukkha—causes of dukkha and cognitive obscurations. I had the impression that you wouldn’t do this meditation for people who are your spiritual teachers.

VTC: You do it for all sentient beings.

Audience: So, it depends on how you see your spiritual teachers?

VTC: Khensur Jampa Tegchok says usually we try and see our spiritual teachers with pure view. He said when it comes to your spiritual teachers, you imagine making offerings to them when you are doing the giving part. If you don’t see your teacher in pure view then yes, do that and take on their afflictive obscurations and cognitive obscurations. You don’t have to see all of your teachers purely, and sometimes it’s hard to.

Audience: When we experience a particular kind of suffering, like knee pain for example, can we experience that we would take all of the knee pain from others, so they are free of that?

VTC: Right. This is a very good meditation to do when you have some problem. When your knees hurt, you think of all the sentient beings who have knee pain, and you imagine taking on all of their knee pain. And you think, “As long as I am going through that, may it suffice for all the different people who have pain in their knees.” There’s a whole lot of people on this planet who have pain in their knees. Some of them can barely even walk. So, it’s helpful to think, “As long as I have that pain, may I take it from others.”

This is also very good to do when you are in a bad mood. “As long as I am in a bad mood, may I take on everybody’s bad mood, and may everybody be free from their bad moods.” And then you do the visualization, and it destroys your own self-centeredness and your own self-grasping. Then you have to imagine your own bad mood being gone. Imagine that. “No, I don’t want to imagine my bad mood going. I like my bad mood. It’s so comfortable.”

This is the whole thing about remembering the teachings and going through them like I was talking about at the beginning of the session. If we go through all these outlines and do all these meditations then when we really need them, we’ll remember them, and we’ll know how to do them. But it’s very true. When we’re in a bad mood, what do we meditate on? Chocolate. “No, sorry, you can’t meditate on chocolate.” “Well then just give me some.” That’s not going to work.

You have to think of how to work with your mind in these different situations. It’s like I often say and have taught many times, what can we do to help somebody who is dying or what can we do to help an animal that’s dying? People have heard it many times, but when their animal is dying, when their neighbor is dying—[mimics dialing the phone] “Hello, what do I do? So and so is dying, what do I do?” Because it’s completely gone out of your mind. Why is it gone out of your mind when you need it? Because you didn’t go over your notes and contemplate the teachings that you heard. When you don’t do that then you’re at a total loss when something happens. “What do I do?”

Audience: Can you also do the tonglen meditation for beings in the bardo and somebody who is actually dying or someone who died some time ago?

VTC: Yes, you can do it for the dukkha of any kind of living being. If somebody is dead and you’re thinking of them in the bardo and the confusion they may be experiencing there then yes, do taking and giving for that.

Audience: Is this something that needs to be done in a formal meditation session, or is it something that as I’m laying in bed with back pain or I’m just walking down the street and thinking of someone that I can do informally, too. Because I’m always breathing.

VTC: Yes, of course. You don’t always need to do this meditation with the breath either. Sometimes when you do it with the breath, because you are breathing, you don’t have enough time to really contemplate and think about it. I really think until you’re very fluent in this meditation, go slowly and don’t do it with your breath. Or just imagine the breath after you’ve meditated for a while about what this dukkha feels like and what you’re taking on yourself and developing the courage to take it on. Really imagine what it’s going to feel like for the other person to be free of it.

Do that for some time before doing it with the breath, and like all meditation, it’s good to do in a meditation session because you have fewer distractions. But, again, like all meditation, do it wherever you are. Whenever there is an opportunity, whenever there is a situation that fits, you do it. You don’t say, “Oh, my back hurts so much I can’t even sit up in bed, so I can’t meditate. I’m just going to lie in bed and feel sorry for myself.” If you can’t sit up in bed because something hurts or because you’re really sick then you meditate lying down. But if you are well, you don’t lie down in bed and meditate. If you are well, it’s the same thing as sitting on the chairs. If you can, sit on the floor. If you really cannot sit on the floor, then sit in the chair. But don’t go to the chair as your first choice. Same thing with this—try and give yourself the best environment, but do it wherever you can and wherever it fits.

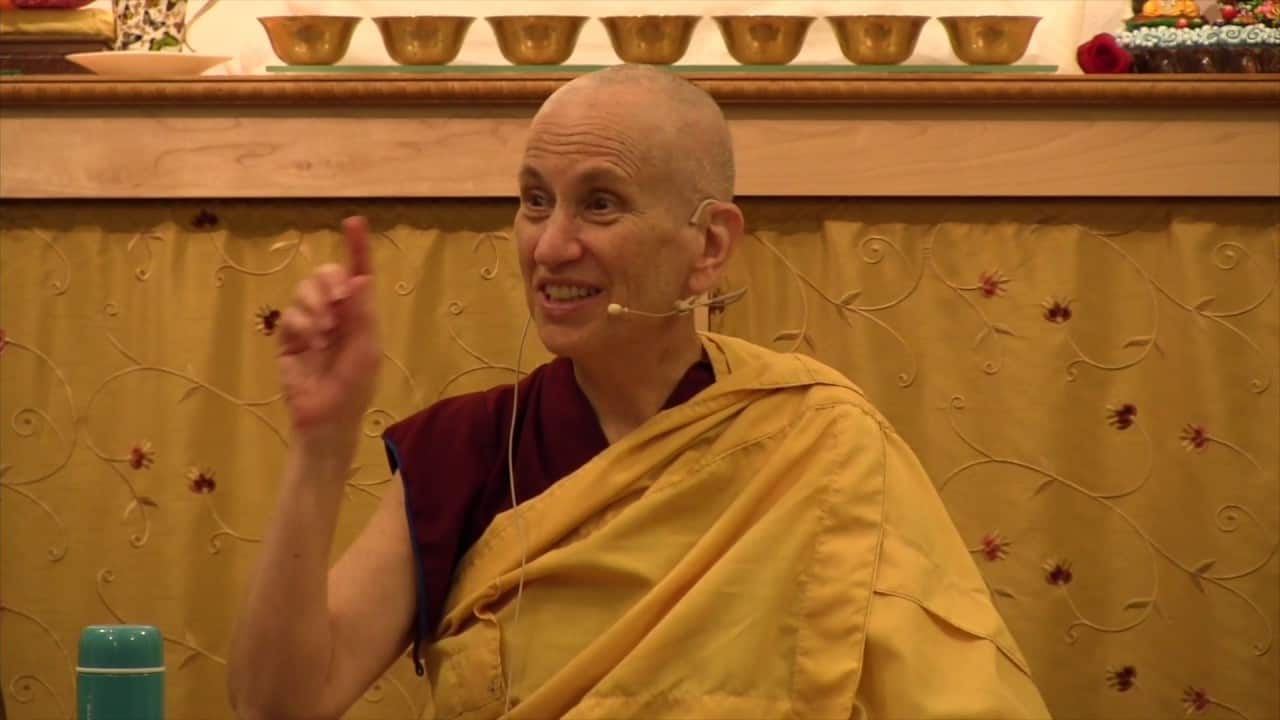

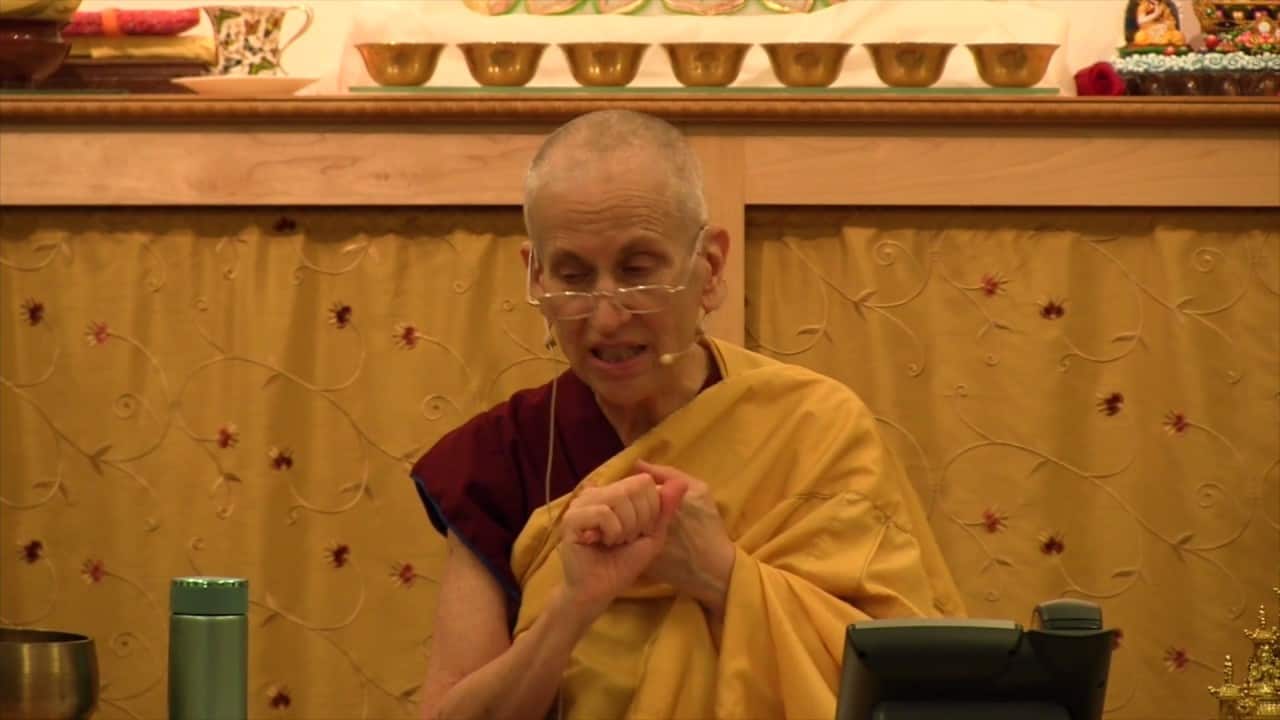

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.