Afflictions arise with a happy or angry mind

Part of a series of short Bodhisattva's Breakfast Corner talks on Langri Tangpa's Eight Verses of Thought Transformation.

- The third verse of the Eight Verses of Thought Transformation

- Encouraging us to be mindful of the afflictions playing in the background of our mind

Verse 3.

In all actions I will examine my mind,

and the moment a disturbing attitude arises,

endangering myself and others,

I will firmly confront it and divert it.

That is our daily practice. Some of the other verses, they talk about specific situations—somebody offends you, somebody betrays your trust, something like that—this verse is for all situations. It doesn’t matter if people treat you nicely or people don’t treat you nicely, afflictions can arise in either case.

Sometimes we think that when people treat us nicely, then, because there’s no anger, we think, “Okay, my mind is free of afflictions.” Wrong. Because sometimes what comes instead is attachment—we’re attached to reputation, to praise, to being important. Or arrogance may come. Something like that. We have to be just as vigilant in checking for afflictions when we’re happy as when we’re unhappy.

This was a difference—in the Mind and Life conferences when scientists were asked between positive and negative emotions, they made the difference on if you feel good, then that’s a positive mental state, and if you feel unhappy, that’s a negative mental state. But from the Buddhist perspective that’s not so. Because, like I just said, you can feel happy and have afflictions all over the place. That makes it difficult to recognize them, because you feel good, so there’s nothing to look at. We also usually think, “If I feel lousy, then then an affliction is present.”

It came out in those discussions—His Holiness pointed out—that, for example, if you’re meditating on the defects of cyclic existence, your mind might get quite sober. Not this giddy excitement, but really like [horrified], and that isn’t what we’d call a happy state of mind, but it’s a very virtuous state of mind.

Just because our mind feels sober, not just bubbling over with joy, doesn’t mean that there’s non-virtue. It could mean that it’s a certain kind of virtuous mind. Sometimes even when we have compassion for others, again, our mind may not be bubbling over with excitement, or even happy, but it’s still quite a virtuous state of mind.

We have to learn to discriminate virtue and non-virtue in a way that’s quite different than happy and unhappy, and what many people would say are virtuous and non-virtuous states of mind.

For example, in therapy the purpose is that so you can adjust to, and act in a reasonable way, and content way, in your interactions with other people. That may be one of the purposes of therapy. And you may accomplish that purpose. But you may have attachment come up in the process of it, because what therapy is trying to do, it assumes that the afflictions are normal, and that we’re going to have them, and it just tries to balance them so that you don’t get so carried away that you make a lot of problems for yourself and you’re tremendously unhappy.

What I’m getting at is in Buddhism we have specific standards for virtue and non-virtue that are quite different from what we’ve grown up with, either in our family, in therapeutic situations, or even in other religions.

I remember an example of the last one. When we lived in France, there was a group of Catholic nuns that we would go to visit. Sometimes we stayed over night there. I remember one time we were eating a meal and there was some kind of bug that crawled around, and one of the sisters just grabbed her shoe and smashed it, while the Buddhist nuns were going, “No don’t do that!” And she was so surprised by our reaction, and that led to a big discussion about why do we consider it non-virtuous to kill insects. For them, it’s very good because insects carry disease and they bother you and they bite you.

In this verse here, where it’s asking us to always examine our mind, we’re looking to discern virtue and non-virtue. So we really have to examine what those two are from a Buddhist viewpoint, not from the viewpoint of the religion we grew up with, or our therapist, or our friends, or general society.

There’s a lot to say on this verse, I’ll keep on it for a while, but I think that’s one major point to really think about, and to get an idea of how to differentiate virtue and non-virtue. That’s where studying the scriptures is really helpful.

At the beginning of Precious Garland, the first chapter, Nagarjuna talks about 16 practices to do. Ten were to abandon the ten non-virtues. The other three to abandon and the three to practice: abandon intoxicants, abandon harming others, abandon wrong livelihood. The three others to practice: generosity, respecting those worthy of respect, and love. You remember those and that helps you to discern virtue and non-virtue.

When you read the Good Karma book and root text there by Dharmaraksita, The Wheel of Sharp Weapons, that also teaches you a lot about karma—what are the causes of nonvirtue—what we’ve done, and you can tell if you abandon those, then that’s virtue, and if you do their opposite it’s virtue, too.

It’s very helpful to do these kinds of studies. Also there’s the Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish. When we study about refuge and to do the refuge ngondro, or even in taking refuge in our daily practice, there’s the explanation about negativities that we create in relationship to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, and to our spiritual teacher, so it’s very helpful to study those things too. In the 35 Buddhas it mentions some of the things to abandon. There are a lot of places where we can get information about this. Then to really think about it so we can identify virtue and non-virtue in our own experience.

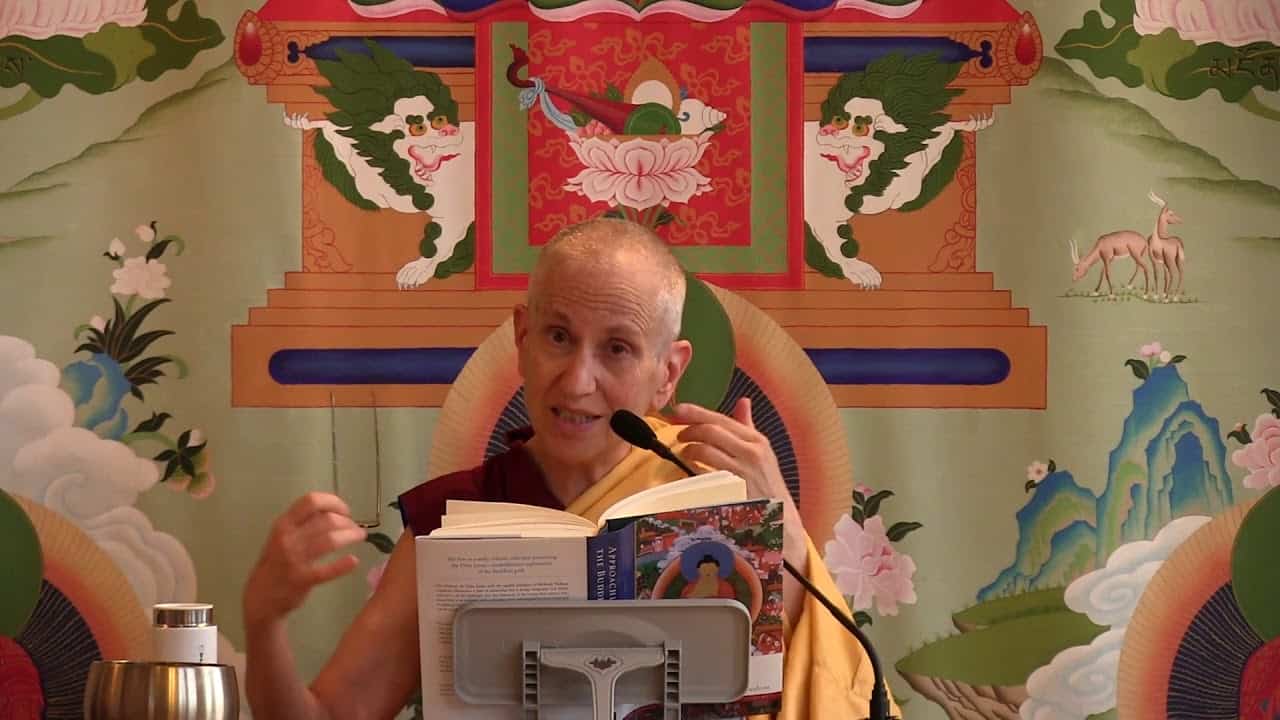

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.