Giving up grasping

Part of a series of teachings on the text The Essence of a Human Life: Words of Advice for Lay Practitioners by Je Rinpoche (Lama Tsongkhapa).

- How remembering our mortality helps us set our values—an emphasis in this text

- Importance of developing a heart of renunciation now

- Looking at the unsatisfactoriness of samsara

- How we must separate from our body, possessions, friends, and family

The Essence of a Human Life: Giving up grasping (download)

We’ve been going through Je Tsongkhapa’s The Essence of a Human Life: Words of Advice for the Lay Practitioner.

He’s talking about death. Actually he spends quite a few verses talking about death. It’s kind of a major emphasis of this piece. So he’s been saying to remember that death is certain, the time of death is uncertain, and that without remembering death we won’t create any virtue. That that’s the big thing, remembering our own mortality, that helps us set our values, it helps us set our priorities, and pulls us out of our lethargy, our complacency, our “well, everything’s great, it’s … well it’s not so shiny today, but kind of…. At least it’s not in the 90s. Life is good.” You know, that kind of complacency. So when we remember our mortality it wakes us up and asks us to question what’s the meaning of our life.

So he continues here:

Think, therefore, upon seeing and hearing of others’ deaths,

“I am no different, death will soon come,

its certainty in no doubt, but no certainty as to when.

I must say farewell to my body, wealth, and friends,

but good and bad deeds will follow like shadows.

“I must say farewell to my body, wealth, and friends.” It’s just one sentence and some people may look at it and go, “Hmm, that sounds kind of tough.” And other people may look at it and go, “Oh, no problem.” But I think it’s actually pretty tough. Because if you look at it even in our life, are we okay with giving up our body, wealth, and friends and family? No, we aren’t okay with that at all. There’s a tremendous sense of possession–“These are mine and I need them. I want them. They’re the source of happiness and pleasure for me. And I don’t want to give them up.”

This is kind of our attitude in life. And then the phenomenon of death doesn’t give us a choice. It says, “Whether you like it or not, it’s time to give things up.” So then what do we do? Do we just kind of wait until the moment of death comes and then deal with it then? Or do we practice giving things up now, and lessening our attachment now, so that when the time of death comes then it’s not going to be a problem for us.

The great masters say, “Practice now.” And develop a heart of renunciation now. And here when we’re talking about renunciation, we’re not renouncing happiness. Buddhism is not about “give up your happiness.” Buddhism is about “here’s a way to find a stable state of happiness.” So what we’re renouncing is dukkha, all the unsatisfactory things.

But so much of our problem is that we don’t realize unsatisfactory things as unsatisfactory, and instead we think of them as the cause of happiness. So we have a very limited view on things.

For example, our body. Have you ever wondered, “Why do I have a body?” It’s an interesting question. “Why do I have a body? How did I get this body? What does it mean to have a body?” Because we drag this thing around all day. And we pamper it to bits. And why do we have it in the first place? We don’t usually ask that question. And if we do, then we say, “Well, it’s who I am.” You know? “You can’t separate me from my body. I am my body.” Or, “It’s my body but I’m union-oneness with what’s mine.” And so we just assume that the body’s always here and that our whole identity is based on this body. And so at the time of death we have to separate from this body, and the mind goes, “Ahhhh! Who am I going to be if I don’t have a body?” Because the whole life we’ve spent with this body. “Who am I going to be if I don’t have this?”

And so because of this intense grasping—we want to exist—then if we’re losing this body, how to solve the problem? We cling to another one. And so that’s what ripens the karma that throws us into another rebirth. It’s like, can’t have this one anymore, let’s grab another one. Not realizing that as soon as we grab another body then we are putting ourselves in the same position that we’re in now, which is living with a thing that gets old, and sick, and dies.

Now, most people don’t look at the body that way, until they get old, and sick, and come towards death. But when you’re young your body is fun. Until it isn’t. Because there are lots of people who get sick when they’re young. And the pain that the body can cause, and the distress that the body can cause, is no joke. But we usually see the body as something just so wonderful. “Look, I can go skiing. I can do….” What do you call that? You throw the disc…. Well, yes, throw the frisbee. And the other one, that the athletes do in the Olympics…. The javelin. All those kinds of things. “Look what I can do, I can throw this thing so far. This body is fantastic.” Or, “Look, I can dance…..” And I think the latest thing you when you’re doing, you’re doing back-bends or something. “Look what I can do when I’m dancing, this body is great. And I can do all these fun things with the body and go white river rafting, and….” You know?

But really, is that so much fun? It’s stuff that lasts a short while, you can get killed in the process of doing a lot of these fun things. And people do get killed. Like, “Let’s drive a race car….”

We don’t really stop and think, “What’s my relationship with this body? And how am I going to feel when it’s time to give this body up?” And when I say to myself, “Who am I going to be without this body?” then what answer am I going to give myself in the death process? Is there any kind of experience of selflessness, of emptiness to rely on that will help us release the pain of separating from the body and from all of the identities.

Something to think about. Separating from all of our possessions, too. Again, no choice. They stay here, we go on. Doesn’t matter how many paper computers, and paper refrigerators, and paper speed boats that your relatives burn for you. And how much money from the bank of hell they send you. [laughter] None of it comes with.

It’s interesting, they burn money from the bank of hell, but they keep the real money for themselves. The friends and relatives. Which is what happens, isn’t it? You work very hard for your possessions, and then your descendents fight over them. And I used to say this just as like a matter of fact. And then it happened in my own family. Which I never expected. So it’s really true.

And then friends and relatives, same thing. There’s no choice. When death comes, we have to say farewell. And are we prepared for that? Or are we deeply attached to people? So it’s a question to ask ourselves and to look at. And the great masters say, well, in preparation for death learn to give up these attachments.

It doesn’t mean that you give away your body now, and you give away your possessions now, and you don’t have any friends or relatives from now on. It doesn’t mean that. I mean, we still live in a world with these things. But it means that we loosen the clinging, and the craving, and the grasping, and the stickiness regarding all of those things. And then, if we can do that well, then they say that dying is like going on a picnic. That it’s really pleasant. A really wonderful experience. May we create the cause for that to happen.

[In response to audience] Do we substitute spiritual mentors for objects of attachment? We often do that. You know, we look to our spiritual mentors, and they’re going to fulfill all of our emotional needs that mom and dad never did…. Until they don’t. If you have a good spiritual mentor they’re not going to fall into that hook. But often that’s what people want, is somebody who’s going to give them all the love, and attention, and encouragement that mom and dad didn’t. But that’s not the spiritual mentor’s job. The spiritual mentor’s job is to help us grow.

[In response to audience] Yes, that we haven’t learned other ways, so our automatic way of relating to anybody is [claps hands together] stick. Yes.

Actually, you know, in 1996 when we had this conference in Bodh Gaya, “Life as a Western Buddhist Nun,” there were some lay people who came to volunteer, to help out, and one of them said to me, she said, “I’m really noticing how I relate to people, because I can’t stick to any of these nuns. None of them buy into the stickiness that I’m throwing in front of them.” Interesting. She learned something quite valuable about herself.

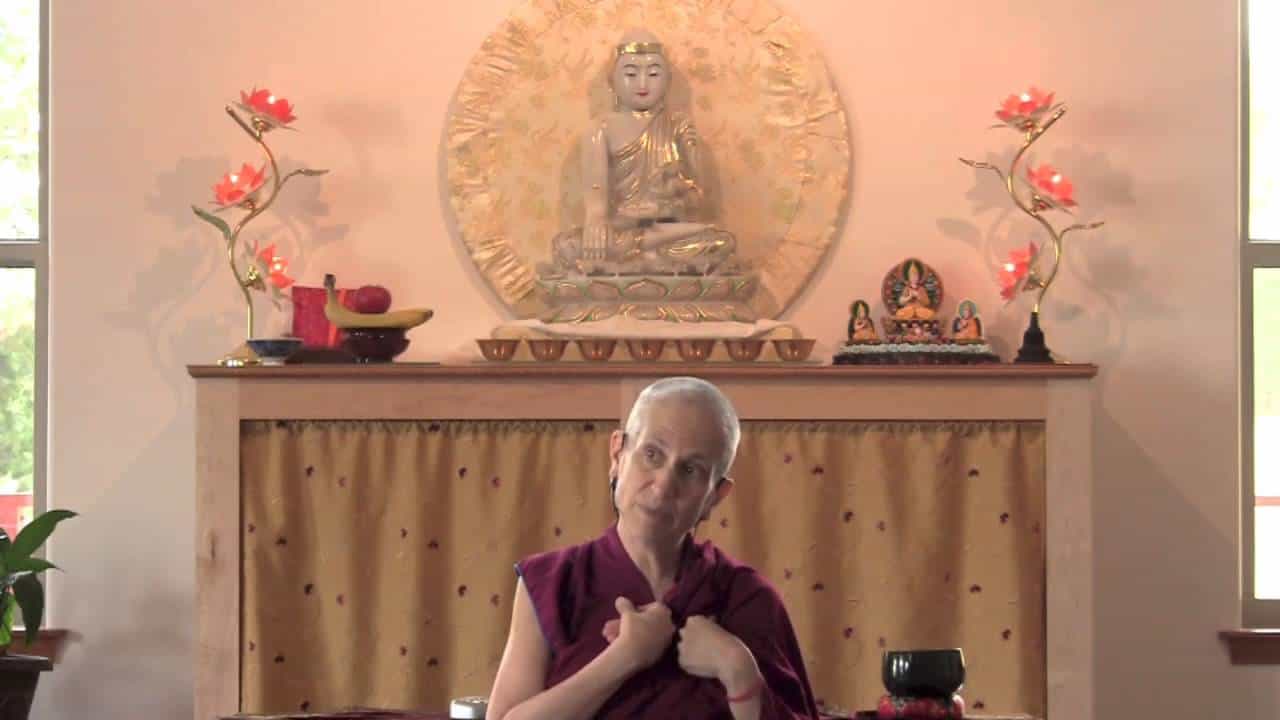

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.