Preparing for death

Part of a series of teachings on the text The Essence of a Human Life: Words of Advice for Lay Practitioners by Je Rinpoche (Lama Tsongkhapa).

- Importance of really considering that death can come at any moment

- How the Abbey community hears about the deaths of many people

- How we view aging and death

- Practicing with the deaths of others that we hear about

The Essence of a Human Life: Preparing for death (download)

Let’s move on to the next verse. The previous one he was talking about death. He continues now:

Think, therefore, upon seeing and hearing of others’ deaths,

“I am no different, death will soon come,

its certainty in no doubt, but no certainty as to when.

I must say farewell to my body, wealth, and friends,

but good and bad deeds will follow like shadows.

I’ll read the next verse, too, because it’s all one thought:

“From bad will come the long and unbearable pain

of the three lower realms;

from good the higher, happier realms

from which to swiftly enter the echelons of enlightenment.”

Know this and think upon it day after day.

Let’s go back to the first verse,

Therefore, upon seeing and hearing of others’ deaths, think

“I am no different, death will soon come,

its certainty is no doubt, but no certainty as to when.

We talked before about how the certainty of death is there, how everybody must die, and how we have no idea when. We always feel it’s going to be later. But even people who are dying today think that today they’re not going to die. Even you’re terminally ill in the hospital you always think it’s not going to be today. It’s going to be tomorrow. Or the next day. Or in a week. People don’t think, “Oh, it’s going to happen today, and by this evening I won’t be here.” Our ignorance is so thick that we can’t see that possibility.

And even when we’re well and healthy we don’t think, “Well, by this evening I won’t be here.” Because again, strokes, brain aneurysms, heart attacks, all these kinds of things, car accidents, they happen to other people. Until they happen to us.

There’s no certainty that none of those things will happen to us, because that’s exactly the way the other people they happened to felt before they happened to them. So we really don’t know.

And the beginning sentence, “upon seeing and hearing of others’ deaths….” Here at the Abbey that happens a lot because people contact us when somebody is very ill or when someone has died. Either they want counselling, or after somebody dies they want us to make prayers and offerings and so on on their loved one’s behalf. So we hear a lot of stories about how people died. Young people, old people, middle (aged) people…. It’s quite amazing.

Sometimes we hear about elderly people and we just go, “Oh, well they’re in their 80s or their 90s, so that’s kind of natural. That’s okay.” From the point of view of the person who died no, it wasn’t okay, they still want to be alive. But in our mind we say, “Oh, that makes sense.” Until we think of somebody who we care about who’s that age, and then, “Oh, 80? 90? That’s too young to die. You need to be older to die.” So strange, isn’t it?

Do you remember when you were younger? I remember so explicitly being in my early 20s and thinking 40 was just ancient. And only people like my parents turned 60. I mean, 60 is really old. You’re almost dead at 60. Until you turn 60. [laughter] And then suddenly 60 is young. And you won’t even say 70 is old anymore because you know 70 is coming soon. So then you put it out 20 years instead of 10 years, 80 is old. But 80 is going to be there soon. Because look, you turned 60. Okay, 20 more years to 80. But 20 years ago you were 40. So it’s not like you were a kid 20 years ago. So from 40 to 60 went real fast. From 60 to 80 is going to go real fast, too.

They tell the story of one disciple who said to his master, “Please give me a warning about my own death so I can prepare.” So the master said, “Sure, I’ll do that.” So then as time is going by the master gets requests to do prayers for various people who have died, and so he tells his disciple about each of those deaths and please make prayers for these persons. And then at some time the disciple gets very ill and it becomes clear that he’s terminal and he’s going to die, and he says to the master, “I thought you were going to give me some warning about when I’m going to die.” And the master said, “What do you think I was doing all those years telling you about all the other people who were dying?” It’s warning of our own death.

Here at the Abbey we hear amazing stories of how people die totally unexpectedly. There was one family that contacted us and their son was 16 years old, mom had just asked him what he wanted for dinner because she was going to a take-out. And then somehow, we don’t know how or what he died from, but by the time mom got home with the meal the kid was dead. Can you imagine how the parents felt like that?

Many, many stories like this. Two young women of one of [audience] friends were in Nepal during the earthquake. They were never heard of again even though their brothers went there and tried to find them.

So whenever we’re asked to make prayers for somebody who died, we should really take it to heart that I might die in this same manner, too. But also at some time or another people are going to be writing emails saying, “Please make prayers for me,” using our name. “Please, Thubten Chodron just died, make prayers for her.” And somebody else will go, “Oh yeah sure, put her on the prayer list.” And then in the evening sometime somebody will read out all the names, “Well, we’re dedicating this person, this person, Thubten Chodron, blah blah blah.” [yawn] [laughter] You know? That’s how meaningful it’s going to be to other people. But it’s sure going to be meaningful to us, isn’t it?

Just recently, in the last few months, two nuns who have been my Dharma sisters since 1975 have died. And both of them were practicing all those years. And yet it’s no guarantee of long life or good death or anything. One of them, she must have been in her mid- late 70s, because she was older than I am. But she suffered from Parkinson’s for many years and she was actually in a nursing home for the last few years. So I think she just…. One morning they couldn’t arouse her, and that was it. But for many years being in the nursing home. I don’t know if Dharma people were there when she was alive. I don’t know how aware she would have been if they were.

The other one just died at Chenrezig Institute. She and I, again, we were friends since ’75, and she had cancer for a number of years and was steadily going downhill. She wound up living longer than people expected, and she was in incredibly good mental state, but death came to her, too. One day there, next day gone.

When you start watching your contemporaries die, and it’s not of accidents–flukie things–but it’s of illnesses that accrue to us as we get old, then it becomes more vivid that our own death is approaching. And there’s no way to avoid it. Then our time becomes our most precious possession. Because other things come and go. But our time–what are we going to do with our time? Because it’s not an unlimited supply of time. It’s a limited supply of time. We don’t know when it’s going to run out. And it’s only with our time that we can create virtue and purify nonvirtue, and learn the Dharma, and contribute to the welfare of others. Body, possessions, all this other stuff, it comes and goes, it’s really not very important. But our time becomes very important. And how we choose to spend our time, and the motivations that we want to have when we’re doing certain activities, becomes much more important. So even if we’re doing activities that we need to do to take care of the Abbey, or just errands or whatever, it becomes more important to us that we need to generate good motivations for doing that, and not just operate on automatic. But really continuously cultivate bodhicitta motivation. And dedicate.

[In response to audience] Actually, there were two lawyers who used to come to Cloud Mountain [retreat center], and I think both of them were still working when they died. One, she had been…. Some friends were over in the evening, I think her son was also over, and they were just talking, having a good time, I don’t know, watching a movie or playing some games, and she went to sleep, everything was fine, she didn’t wake up in the morning. And her son went in and his mom was dead. Totally unexpected.

The other one got ALS and had kind of a long, very debilitating time until she died. But both were professional women, very intelligent, really wanted to put the Dharma into practice and make a difference. But all of that doesn’t stop death from coming. It can help you prepare for death, but it can’t stop death.

And one of them, the one who didn’t wake up in the morning, her friends kind of knew she was interested in Buddhism but she didn’t really speak about it very much, and so she died suddenly…. They didn’t call me for another week. If they had called me right away it would have been so much more beneficial for her. But she kept her practice very quiet. They knew her prayer book was on her bed stand and as they went through papers then they discovered things. But I really wished that they had been able to tell me right away.

Then we also hear of people who commit suicide, which is such a waste of human potential. One person who was quite wealthy, very wealth actually, left most of his estate to charity, but killed himself. Another person who was a—he was young…. I don’t know if he was in Iraq or Afghanistan, but he came back, had a substance abuse problem which completely alienated his family, and wound up jumping off a bridge in Spokane. Young person. So these are incredible tragedies. Because you have a human life, and you have the ability to learn the Dharma, but they never had the karma to actually meet the Dharma. And instead their intelligence got warped by the experiences that they had and wound up thinking that death would alleviate their pain. When it doesn’t.

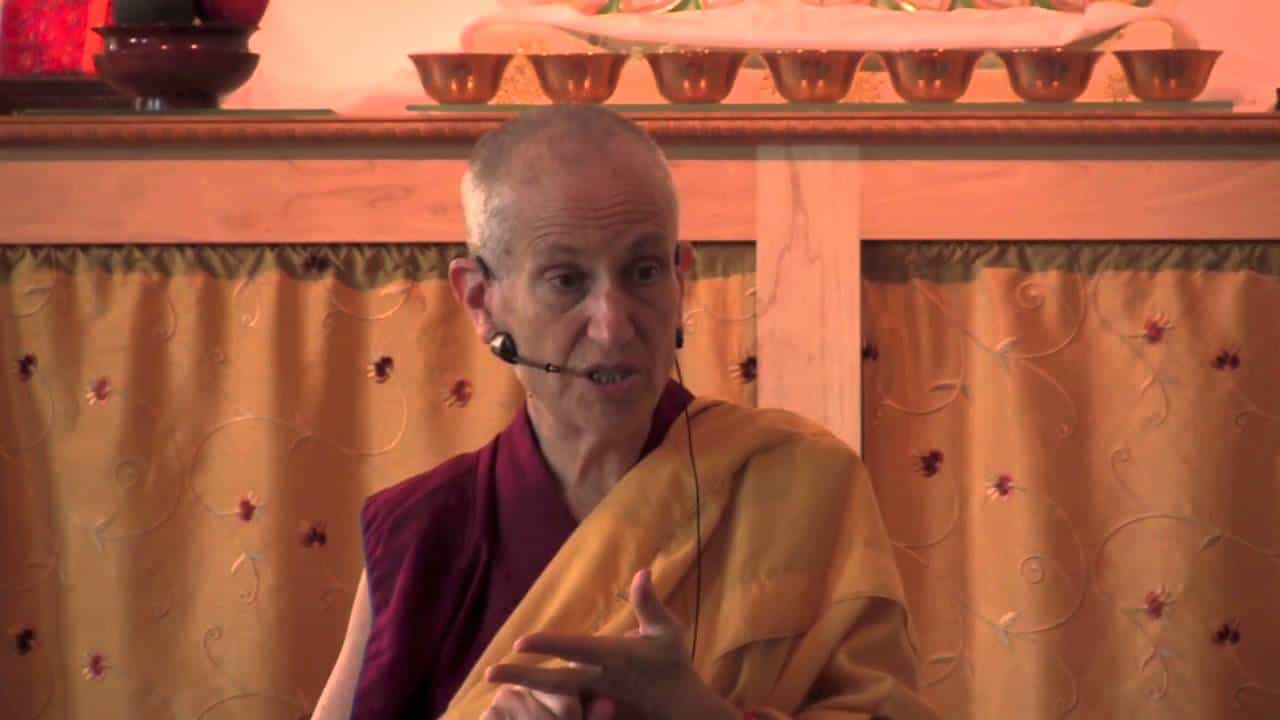

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.