Verse 71: Living an exemplary life

Part of a series of talks on Gems of Wisdom, a poem by the Seventh Dalai Lama.

- It’s not what we know, but who we are as human beings

- Cultivating a loving motivation and making that a part of us

- Ethical conduct is changing our attitude so that it changes our behavior

- Importance of pausing and reviewing our motivation throughout the day

Gems of Wisdom: Verse 71 (download)

Okay, Verse 71:

What is the loving behavior inspiring to all people in the world?

Living an exemplary life that accords with spiritual ways.

What really hits me about this is the exemplary life that accords with spiritual ways is who you are as a human being. So, what’s the loving thought that inspires everybody in the world? It’s not all the knowledge you have. It’s not all the techniques you have of how to listen to people and make them feel good. It’s not all the words of the meditation. It’s not all the books that you’ve read or written on love and compassion, and these things. It’s who you are as a human being.

And that really strikes me. Because so often we get caught up in the techniques. Let’s learn a technique how to communicate with others, but we don’t have the motivation to really care about them, we just want to communicate better with them so that we don’t have so many problems. What this is saying is that our motivation really is of key importance, and that thing of having a loving motivation and that being completely integrated with who we are as a human being.

Many people write and they ask me about doing hospice work. What do you say when you go into a home? What do you say to somebody who’s dying? What do you say to somebody who’s grieving? And I always say, you know, I don’t have a bunch of stock phrases of what to say to somebody who’s dying or somebody who’s grieving that I just pull out of the hat. Because I think that the most important thing when I go into that situation is who I am as an individual that enables me to connect (hopefully) with those people through genuinely wanting to listen to what their cares and concerns are. And I think when we have that heart that genuinely cares about others then the techniques can be very helpful, to help us overcome bad habits of how we say things, and mindless ways in which we say things. But just learning the techniques doesn’t change our attitude. And it’s really our attitude that people pick up on when we’re trying to help them. Or when we’re trying to do anything with them.

The other day we were talking about trying to be a good example to somebody, and the difference between trying to be a good example to somebody and being a good example. When you’re trying to be a good example to somebody there’s a lot of kind of false effort, expectation for some kind of ego reward, or expectation that people will, of course, appreciate our good example and follow it. And that kind of thing of trying to be a good example sabotages the whole project. Whereas when we work on ourselves and we are a good example then we’re not thinking, “Oh, am I a good example?” We just are one because our focus is on having our own introspective awareness, our own conscientiousness, our own kind and loving heart. Rather than trying to look like we are a certain way.

On the other hand, having said that it’s who you are that really matters (I think) when we bring ourselves to different situations. I remember one time, many years ago, being very frustrated with one of my Dharma brothers who thought that all you needed to do was generate bodhicitta and then automatically you could communicate well with everybody. And I was saying no, I don’t really agree with that. Yes, bodhicitta has to be your underlying motivation, but if we have a lot of old habit patterns of how we say some things, of the tone of voice we use, of our body language, of how we listen or don’t listen, or interrupt or don’t interrupt, or words we choose…. That if we don’t have some attention about these “mechanics” (for lack of a better word) of how to communicate, then we can have all the love and compassion we want but our old habits are going to get in the way.

I think, therefore, it is really helpful to learn about mediation and conflict resolution and non-violent communication, and all these things. But I don’t think those are things that are ends in themselves. We really have to work to change our mental attitude.

“What is the loving behavior inspiring to all people in the world? Living an exemplary life that accords with spiritual ways.”

What’s an exemplary life that accords with spiritual ways? I think the first thing about that is ethical conduct. That’s the basis of the whole thing. If we don’t have ethical conduct then how are we ever going to have loving behavior? Loving behavior has to be based on ethical conduct because ethical conduct is defined as not harming. So if we can’t stop harming—if we don’t have the ethical discipline that stops harming—it’s going to be hard for us to have loving behavior that wants to do something good. So a lot of this has to be really grounded on ethical conduct, which unfortunately people don’t talk very much about in society these days. I even changed the term to ethical conduct because I grew up with morality. The moral majority. Just the innuendos of morality is like something dictated to you from outside that you don’t want to do but you have to do. Whereas ethical conduct is something that comes from inside because you really see the benefit to yourself and the benefit to society and to everybody you encounter. So I think that kind of ethical conduct has to be the foundation before we can have loving behavior.

Ethical conduct is not just following rules and precepts and things like that. I know when we study the pratimoksa, the set of our monastic precepts, some people describe the pratimoksa as the world’s oldest legal system. Because it is a series of rules and there’s all sorts of commentary: “This word means this and that word means that. If you do this it’s this degree of offense, if you do that it’s that degree.” So you could read it like a legal book—and some people do, it makes it terribly boring I think. Or you can read it as a guide to training your mind. A guide to making you more aware of your own conduct and your own attitudes, in which case I think it has real purpose and can be very, very interesting, not just as a set of rules.

So ethical conduct is, like I said, not just following rules but really changing our attitude so that it changes our speech so that it changes our behavior. And if we can’t completely change our attitude all at once then at least working on the actions of our body and speech so that even if the mind may not be in a good place at least we can [covers mouth] close our mouth sometimes when we need to, and we can refrain ourselves from doing harmful actions.

Audience: Reminded me of the SAFE group that I’m responding to this week there was one of the participants that spoke about the importance to be aware of any time that we walk into a room how we affect others. If we set the motivation before we do these different actions, even just in terms of going from one place to another, how beneficial that is for ourselves and others.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Yes. So just emphasizing how much we influence each other by everything we do. And even just walking into a room. When you walk into work, or you walk into your family’s home or wherever you walk into, that we’re automatically interrelating with others and we’re going to be influencing them and affecting how they are. And that since that kind of influence is going to happen automatically we might as well make it something beneficial. So therefore I think it can be very good, before we go into situations, to pause and really come back to our motivation. Especially if we’re going to go into a room where there might be people that we have a history with. To stop that history before we walk into the room so we don’t just walk in and punch him in the nose as soon as we say hello. To really pause.

And I think also, for families, when you’re coming home from work, instead of just getting out of the car or off the bus or whatever you do, and open the door and throw yourself down and, “okay, here I am, I’m exhausted from work.” To pause before you go in the door and think, “I’m going to go in and spend time with the people that I cherish the most.” So when I go in I want to go in with a mind that cherishes them and have behavior that shows my affection for them. I’m not just going to go in and take out all my stress on the people I’m living with simply because we’re called a family so therefore they have to put up with me when I’m like this. To really pause and think, “I’m going in to the people I really care about, and let me go in with a good mental state and an attitude of kindness towards them.

That’s kind of, at the Abbey, why we have all these different parts during the day where we do these different verses, because it makes us come back to our motivation again and again.

[In response to audience] So the difference between, in monastic training, starting out looking fake and being fake, and then gradually through transformation you stop looking fake but still inside you’re fake. And then gradually you become genuine both internally and externally. Yes. It’s a process, isn’t it? We don’t get there right away.

[In response to audience] Yes, that’s true. When you have a positive emotion in your mind you can’t simultaneously have a negative one. Sometimes you go back and forth between the two very quickly, but at any particular moment you can’t have both.

Audience: And our body language talks a lot about what is going on inside.

VTC: Yes, our body language expresses a lot. And this is the thing about looking fake and being fake. Because our body language is a dead giveaway. I mean, at the beginning of the practice we are meditating on love and compassion and trying to transform our mind, but then our body and speech, the tone of our voice, just slight things…. We go in and [crosses arms], “Hi, I really care about you and I want to give you some feedback that I think will really benefit you and I’m saying it with compassion.” [laughter] You know, it’s like, wait a minute, that’s not going to work. Because the tone of your voice and your body language are giving away how you really feel.

[In response to audience] Again, from The New York Times, because that’s usually all I read, it was somebody who was shy talking about how she became a public speaker. So I thought, gee, maybe I should read this, I’ll learn something interesting. Well, this person was shy and now can give many talks, but her hints and tips about what to do is write your talk out beforehand and memorize it. Try out certain phrases and if they work very well with people memorize those phrases and use them in another talk. I mean, all of her tips about how to be a good speaker were so … canned. Very good word. Totally canned. And I thought, “I don’t want to be like that.” I mean, I know when I give talks lots of times I use the same examples and I say the same things and some of you have heard these things ad infinitum, but still, the mixture is different and somehow I want to feel like I’m really feeling what I’m saying. I’m not giving a canned, memorized kind of talk about something.

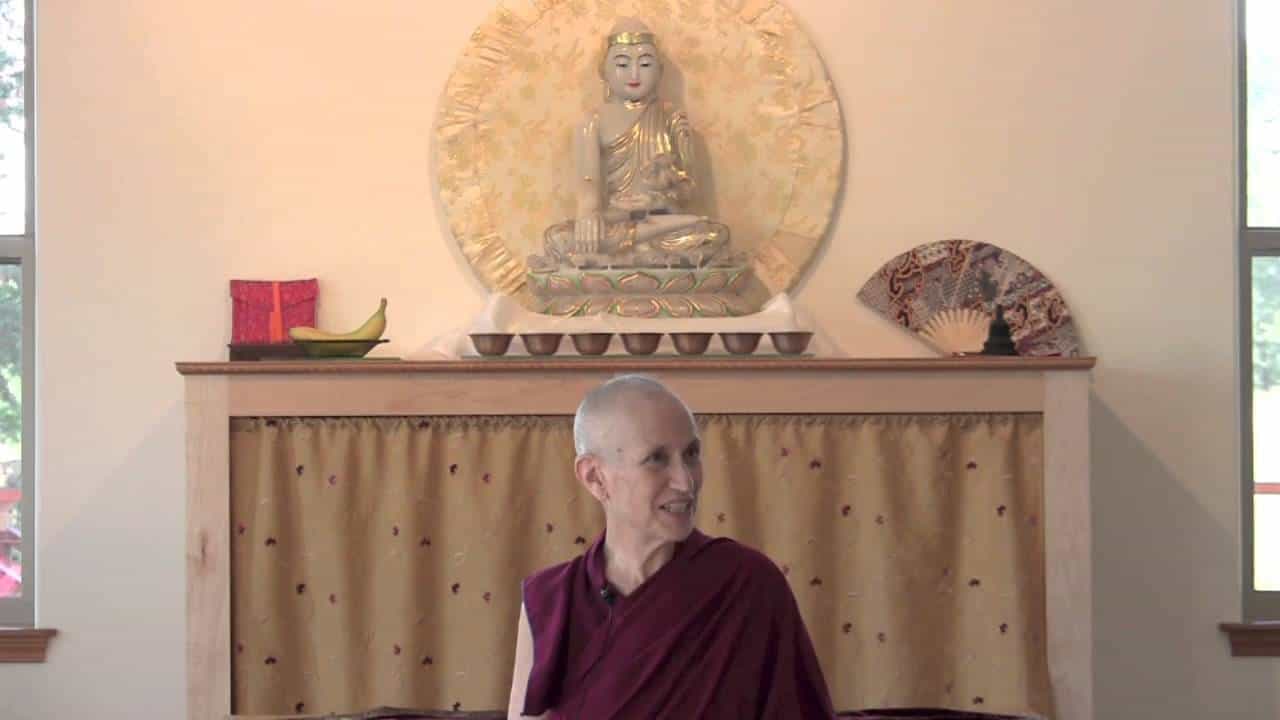

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.