Verse 9: The chains that bind us

Part of a series of talks on Gems of Wisdom, a poem by the Seventh Dalai Lama.

- How the mind of attachment follows us even when we go into retreat

- How we easily fall into habits of doubt and distraction even in a good situation for focused practice

Gems of Wisdom: Verse 9 (download)

The previous verse we did, Verse 8, was, “What is the prison difficult to escape even though we hold the keys?” And the answer was, “Entangled personal relationships such as attachment to family and friends.” Because those entangled personal relationships keep us filled with attachment and worry and fear and trying to please people and all sorts of things like that. Then the next verse follows from that. It says: “What are the chains which bind one even when one has left that prison?”

Audience: Nostalgia.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: You’re getting there! “Attachment to worldly activities even when living in retreat.”

What are the chains which bind one even when one has left that prison?

Attachment to worldly activities even when living in retreat.

“Worldly activities” doesn’t just mean things we do, but it also means the things we think about. You may separate from these entangled relationships on a physical level, and go off to the monastery or go to do retreat or whatever, but then what is your mind filled with when it’s there? Your old habits. You guessed nostalgia, so that sounds like your old habit. We look back on the worldly activities that we used to do and go, “Oh, that was so nice, that was so wonderful. Remember the good old days…. Remember the good times….” And we fill our minds with all sorts of wonderful memories.

That’s what nostalgia is, it’s a fabricated past, isn’t it? We fabricate these wonderful things and, “I miss it, and I want it, and how was it that I left it?” And so we fabricate something and then our mind is totally distracted even though our body is at a monastery or in retreat.

Others of us may have different patterns. Here it was focused around attachment. Attachment to worldly activities. So it could be, maybe we’re the kind of person who gets involved in everybody’s business and has to fix all of their problems. A problem-fixer. So you go off to the monastery, you go off to retreat, what are you thinking about all day? “Oh, so-and-so has this problem, so and so is depressed, so and so is suicidal, oh these people don’t have enough money to live, what’s going to happen? This is going to happen, this, this…. How can I fix it? Oh my relatives don’t have enough money, maybe I should open a business and get them some more money. Maybe I should call them and make sure they’re okay. Maybe I should go on Facebook and converse with them. Maybe I should send them a Dharma book…. Maybe…. maybe….” And our mind is, again, completely filled with all of our old habits, trying to fix everybody’s problems. And slip them an email, slip them a letter. Just a little short note…. You know, that we tell ourselves just to let them know that we care. But actually, there we are going and trying to problem-solve.

I knew one person who, finally, after years of effort, building a retreat house, furnishing it really nicely, being in a very good environment, got into retreat and then—I can’t remember if this person had visa problems or not, but the other people around had visa problems. So all of a sudden she’s the one trying to go down to the foreign registration office and talk them into giving people visas, etc…. And so ended the retreat. Because your mind just gets carried away with different things.

Or you go to the monastery, you go to the retreat place, and you keep thinking about all of the projects that you were involved in before that were so good and so beneficial. And, “Maybe I should go back. You know, I did Reiki before, I was really helping people. So maybe I should go back and do that. Or I should do physical therapy. I was really helping people then. Now I’m just sitting here, you know? Kind of looking at my navel and, you know? I want to do something. I was a teacher before. I was really helping people. I saw the result of it. I was a therapist before. I was….” You know, whatever you were before. “And so I was really helping people with them, and maybe that’s really more valuable….” And so your mind goes into habitual doubt, because that’s a habitual way of thinking. With attachment to being somebody. “I was in the military before. I had this kind of rank and I did this and that….” Whatever it was.

There we were. Attachment to our old identity, attachment to feeling like we had a place in the world. Sometimes when you go into the monastery, you go off and do a retreat, it’s like, “Well who am I?” And then, “Well I’d better establish an identity pretty quick.”

Watch for all of these old habitual ways that attachment comes out even though we may extract ourselves from the physical situation. Restraining the mind and re-forming our mental habits is very difficult.

There’s a story about the Fifth Dalai Lama, the Great Fifth, as he’s called. When he was very young one lama who had clairvoyant powers came to visit him and the young Dalai Lama’s attendant turned him back saying, “He’s in retreat.” And the lama said, “Well, tell him that I saw him in the marketplace this morning.” And later, during the break-time of the retreat the attendant told that to the young Dalai Lama, and he said, “Well yeah, that was true, I got really distracted in my meditation and I was dreaming about the marketplace.” So, it happens to everybody, I think.

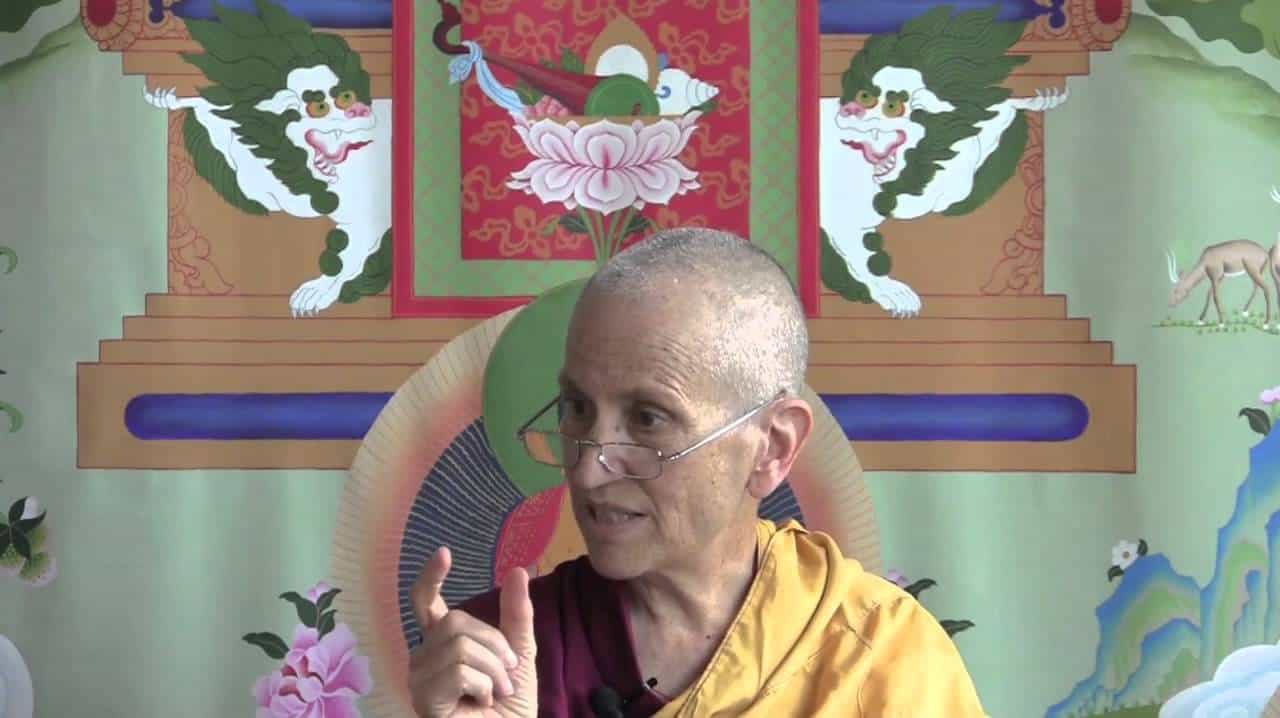

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.