Verse 54: The cunning thief

Part of a series of talks on Gems of Wisdom, a poem by the Seventh Dalai Lama.

- Doubt keeps us from making a true commitment

- Unless we have confidence that the path will take us where we want to go, we won’t practice it

- We need to differentiate between doubt and honest questioning

Gems of Wisdom: Verse 54 (download)

What cunning thief steals cherished gems out of one’s very hand?

Doubt which is double-pointed as regards spiritual practice.

When you think of the cherished gems as the Dharma teachings and the methods to practice… We’ve heard teachings, we have books, we have everything we need, it’s all in our hand. And doubt comes and grabs it away and takes it.

How does doubt do that? By not having confidence and faith in the process of the path. If we don’t have confidence in the process of what we’re doing then we’re not going to do it. We’re going to hem and haw and this and that. It’s like any kind of endeavor that you undertake to do—if you don’t think it’s going to take you where you want to go, then you’re not going to get on. You don’t go to the train station and, “Well I don’t know which way…. I’m not sure if this is the right train to take me to where I want to go but I’ll get on it anyway.” No, people won’t do that. They’ll just stand there until they know which train to take.

But if our Dharma practice is like that—because we haven’t thought things through clearly and doubt keeps coming to plague us—then we never engage in the practice. We just stand there.

That would be like somebody having the correct information on what train to get on, but standing on the platform and going, “Well I don’t know if this is really the correct information. Maybe this train doesn’t really go there. Maybe it goes somewhere else.” And so as a result you don’t get on.

The same thing happens with spiritual practice. We may hear teachings and so on, but unless we have confidence that they’re going to work, and the path is something viable and it’s going to take us where we want to go, then we don’t practice. That is the thief of doubt stealing the gems out of our hand.

It’s interesting to watch our mind and to see when doubt comes up. And also especially to learn to differentiate between doubt and curiosity. Doubt and questioning. Because we’re really encouraged to question. I mean we have to encourage. Especially Aryadeva has been really saying you’ve got to understand the teachings and you’ve got to question. And His Holiness always saying you have to use reasoning. We don’t just use belief without investigation and say, “Well it sounds good, sure.” Because then who knows what in the world we’re going to wind up following. So we need that process of learning and investigating and using reasoning and checking and everything.

But what doubt is is you’ve done that but maybe you haven’t done it so well. Or maybe you haven’t really spent the time thinking about the reasoning and so the mind is still quite confused. Sometimes it’s because we have in our mind old preconceptions from very long ago that really torment us. Maybe you grew up, let’s say, in a very theistic family and even though the idea of emptiness sounds fantastic and you think about it and it makes sense, and karma makes sense to you, somehow you can’t really believe that meditating on emptiness is going to get rid of your ignorance because in the back of your head you were conditioned for a long time that it’s God who’s going to take care of everything. And so you have to, again, come back and use reasoning and say, “Is it possible for this kind of God to exist and to take care of everything and free me?” Okay? So the doubt comes up, very often, because of old stuff that we haven’t really investigated enough to clear away. We really have to do that.

We want faith and confidence that is based on reasoning, but it isn’t so stuck on reasoning that we have to be able to explain every tiny detail before we do anything, because otherwise, again, we won’t do anything. But in the process of developing confidence and trust in the Dharma we don’t want to go to the extreme of undiscriminating faith that, well, yes, somebody else said it who’s a Buddhist, therefore I believe. Because that doesn’t work either.

We need a mind that has curiosity, that asks questions, wants to think, and wants to examine, but that also is still willing—based on what we already know—to go ahead instead of saying, “I have to understand absolutely everything forever before I do anything.”

Because the doubt is—you’ve heard me say this before—it’s like a two-pointed needle. You start to go this way but the other point is sticking there and you can’t go and you start to go that way, you know. And so you wind up not doing anything except poking yourself with both sides of the needle. Which certainly isn’t very productive.

It’s very important to learn to recognize doubt when it arises in our mind, because if we don’t it’s very easy for us to confuse doubt with the process of, “I really want to understand.” So you can tell doubt because there’s a certain flavor in the mind when there’s doubt. You’re really kind of going towards skepticism… Because doubt is an affliction, so there’s some kind of an uneasy feeling when it’s in our mind. Whereas when there’s interest and curiosity and we don’t understand everything yet, then there’s some kind of eagerness and enthusiasm to learn. Whereas with doubt it’s, “Well I don’t know, mmmm… Hmm… Uhhh…” Okay? And that doesn’t get us anywhere.

Sometimes when doubt comes in the mind you have to see: Is it interest, and I really need to sit and look up the answers to something or ask questions and think about it? Or is this just doubt coming up as an affliction to kind of bug me and torment me and make me immobile? And to be able to see the difference. So if it’s doubt coming up in the latter way then you just have to say, “I’m not listening to it.” And really think about the disadvantages of doubt.

[In response to audience] You’re saying in some ways we’re applying a double standard. That things that we learned about before, maybe about God or science or who-knows-what, we just take unexamined because somebody who we respect as an authority said it and we’ve never applied reasoning and so our default is, yes, somebody said that, I believe. Then when we come to Buddhism we start using reasoning, and of course not everything’s totally clear when we start using reasoning, but we never think “oh I should use this reasoning on what I have unquestioning faith in.” Yes, good point. So then we default to: “I’ll believe it if I can see it.” Which is another kind of doubt, isn’t it?

[In response to audience] This is a good tip on how to differentiate them, that the afflicted doubt makes us worry and makes us lose energy, and the questioning, interested, “I want to learn” kind of doubt gives us a lot of enthusiasm. Yes.

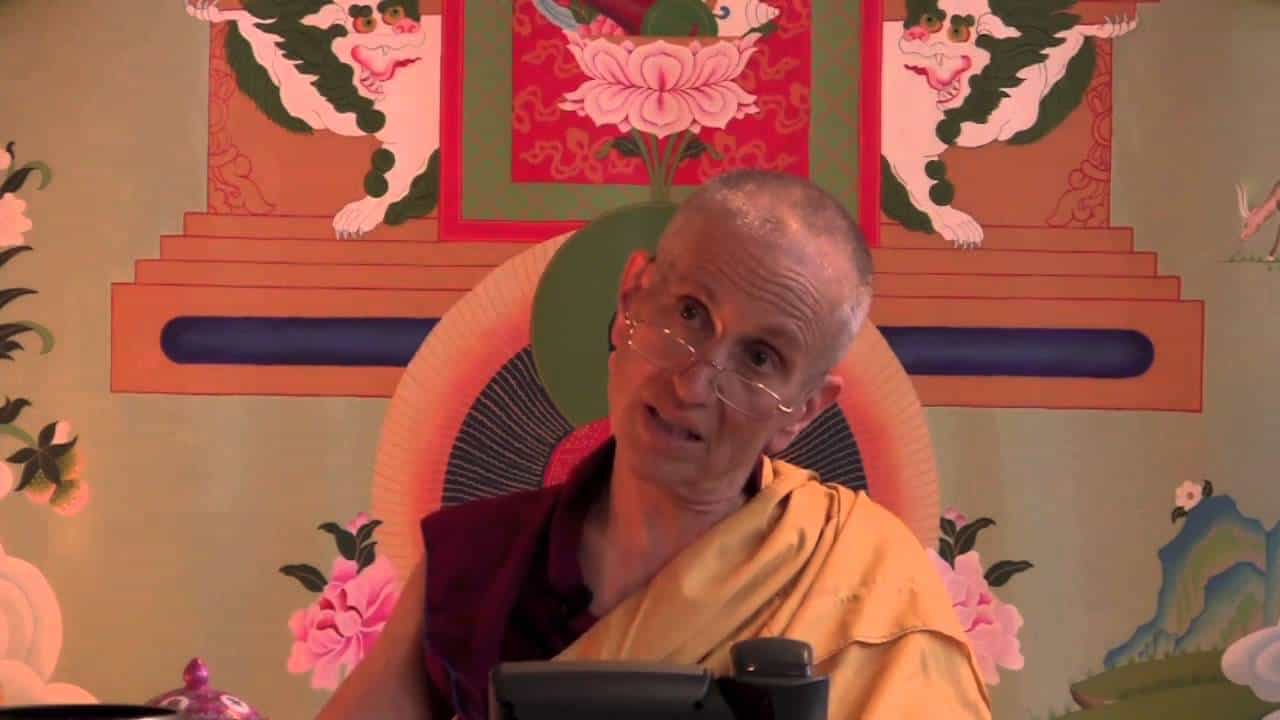

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.