Verse 44: The powerful demon of doubt

Part of a series of talks on Gems of Wisdom, a poem by the Seventh Dalai Lama.

- There are different kinds of doubt, both in a Dharma sense and in a worldly sense

- We have so many opportunities it’s difficult to make decisions

- When we do make a decision we should really engage in it

Gems of Wisdom: Verse 44 (download)

What powerful demon can topple even the strongest person?

Wavering indecisive thought unable to decide on the right course of action.

This is talking about the mental factor of doubt.

There are different kinds of doubt. In general, doubt is a two-pointed mind. “Shall I do this? Shall I do that?” Sometimes it’s three- or four-pointed. “This one or that choice, maybe this one or that one….” Nowadays we have many more choices than people in the past had.

They say doubt is like trying to sew with a two-pointed needle. You stick the needle in and you can’t move. There’s not way that you can take a stitch.

In a Dharma sense, there’s doubt inclined toward wrong views, there’s doubt inclined towards right views, and doubt that’s kind of somewhere in the middle. We usually start out with wrong views, and then go to doubt inclined towards the wrong views, and then the middle,doubt, and then towards right views, and then on to right views, and so forth.

But not only in terms of Dharma views—view of emptiness or whatever—do we have doubts, but just in our own lives. “Should I do this or should I do that?” And we sit there and we waver and we mull over it and we ponder it and we talk about it incessantly with fifty-million different people to gather everybody’s advice…. [laughter] And then we sit there and be confused. Unless, in the back of our mind, we already know what we want to do, but we don’t have enough confidence to do it, in which case we talk to the fifty-million people until one of them tells us what we want to hear. And then we say, “I’ll follow that one.” And ignore the advice that everybody else gave us beforehand.

I think doubt has a special kind of role in our culture because people have more opportunities now, and more choices to make. So then it’s very easy to get confused because there’s so many things that you could do or be or have. I’ve seen people, you know, you’re kind of standing here and say, “Well should I do this or should I do that?” And then the mind would like to try and do this, “But if I try and do this then I’ll have to give up that. And I don’t want to give up that. I want to keep the option open to do that, which means I can’t do this. But if I do that then I have to give up the option to do this, and I don’t want to give up that either. So I want to have all my doors open…..” And so then the “C” word becomes terrifying. And the C-word is not cancer. It’s commitment. It’s like, because if I commit to one thing I have to give up another and…. I can’t…. No. And so then we just stay there in the middle unable to do anything in our lives. Because we can’t make a commitment to anything because it might be the wrong decision!

What we would really like is: I want to choose this, be able to do it for however long I feel like doing it, and if it doesn’t work out, come back to the exact same moment in time where I am right now and choose the other one and do that, knowing that that one would be better. Except maybe it won’t be the better, because if it were then I should do that one first…. So that would be good, let me do that for a period of time and then can’t I come back to this moment again, rewind the time machine maybe two months, maybe two years, maybe twenty years…. Maybe you’re whole lifetime? I don’t like this decision I made, how I lived my life, can’t I come back here and do it differently, choose the other option?

And so people just get paralyzed, not being able to move in their lives because of this fear of making the “wrong decision.” As if there is a pre-planned right and a pre-planned wrong. And as if making the “wrong decision” will totally ruin your life forever; in other words, they don’t give themselves the possibility of, “Okay, I will try that. If it doesn’t work out, I will learn from the experience, and I’ll think about what did I do that caused me to choose that and what was going on and so on. And I’ll learn from it in some way so that I can go forward in my life.” Because if you don’t do that then, okay, you don’t want to make a decision. When you finally make a decision, if it’s not the glorious paradise that you thought it was going to be then if you can’t learn from it you become very bitter. And I think we’ve all met bitter old people, and that is miserable. Who wants to be a bitter, old person?

There has to be ability to decide, but also to learn from our decisions. And to see it as a success when we have done something and even figured out, well, that wasn’t the right course of action, I’ll do the other thing. And then change course and do what we should do when we finally realize that, and learn from our experiences. There’s actually quite a bit tangled up in this mind of doubt.

And then, of course, the opposite to the mind of doubt is the impetuous mind that, an idea pops into our mind and we act on it immediately, without thinking, you know, well what are the long-term results and how is my decision going to affect other people? We just think, “Well that sounds good, let’s commit my whole life to that right now.” Either way is not too wise.

[In response to audience] And actually, the inaction of not making a decision is an action. And there are results that derive from not making a decision.

[In response to audience] Okay, so then interplay between using reason and practicality insomuch as a criteria for making a decision, and doing something because you feel it in your heart. And there’s kind of the thing: Well how can I trust my reasoning and how can I trust my heart? Because sometimes our reasoning process is good. Sometimes our reasoning process is lousy, it’s a bunch of rationalizations, like you say. Sometimes our heartfelt thing is really good. And sometimes our heartfelt thing is just pure emotional garbage. So it’s like, how do you know when you’re having reliable reasoning, reliable heart, or unreliable reasoning, unreliable heart?

For me it’s come from learning from experience. And learning to detect in my own mind…. Because I can see when I’m making up an argument, sometimes there’s a certain feeling in it and I know: there’s an affliction involved in this one. The argument makes great sense but there’s a feeling in my mind: “There’s an affliction. I need to stop and get rid of this affliction before saying anything.” And then I’ll work on it for a while. And then I’ll be able to have a line of reasoning that inside feels calm and I know there’s no affliction with that. And then I know, okay, that’s good to do.

Similarly, with my heart. I know there’s a certain quality of the mind, or feeling, or texture in the mind, flavor of the mind…. I don’t know what word to use to describe it. But a certain kind of feeling when I know it’s garbage, emotion. You know, if I stop myself, “I know this is garbage. This is not right.” And so similarly, if I wait and work myself through that until there’s kind of an emotion that feels clean and clear.

But also what I’ve noticed is, for me, my reasoning and my emotion go very much together. Because if I have a good line of reasoning, my heart feels very calm. And if I have a lousy line of reasoning, I’m agitated. And if I’m agitated, if I look behind that I’m usually rationalizing and making something up or blaming somebody. Or if I have a good kind of emotional feeling there’s usually some reasoned decision-making process in there. So I don’t see those two things as totally different.

[In response to audience] Can doubt be positive? If you’re doubting a wrong view. In that way, yes, because remember I said there was doubt inclined towards the wrong view and doubt inclined towards the right view. The one inclined towards the right view is definitely better than the one…. So if you have a wrong view, like “nothing matters anyway,” and you begin to think, “well no, things do matter, and I can create happiness and I can create suffering for self and others.” You may not be totally sure about it, but that positive doubt is leading you in the right direction. Because that nihilistic view is definitely a dead-end.

[In response to audience] Often when we are trying to be a people-pleaser we get very stuck in doubt. This is a very good point. Because it’s like, “I want to make that person happy because then they’ll do something that will make me happy.” Or, “I want to make that person happy because then they’ll like me. And I want to be liked. I don’t like being disliked.” Or, “I want to say something nice to this person because then they’ll say something nice about me, or they’ll nominate me for the promotion,” or whatever it is. But then the doubt comes in because inside we know that our motivation isn’t right. We know that somewhere inside. And yet we’re like, “I’m so attached to my reputation, and my praise and approval, that I’ve got to come up with some good reason that pleasing this person is really the right thing to do.” But you can’t come up with a good reason when the motivation is lousy. It just isn’t to be had. I actually find it quite exciting about Dharma practice when I get to that point and then I go, “Ah, my motivation is lousy. Look at me. I’m trying to be a people-pleaser. Finally, I figured it out. This has been a habit that’s plagued me how much of my life? And now at least I can see it clearly. This is great!”

[In response to audience] Yes, that’s a very good point, too. That often, why are we indecisive? Because our criteria is not: Which choice will help me practice the path? Which choice will help me develop bodhicitta? What choice will help me live a more ethical life? Our criteria is: How will I experience the most pleasure? And then we get tied up: “Oh that looks good, that looks good, too….” And then…. When pleasure is the criteria we never know what’s going to bring us the most pleasure. And then we sit there and worry about it. Because who wants to have Grade B pleasure when we can have Grade A pleasure? So we stay in a mental state of Grade C pleasure because we’re so neurotic about the whole thing.

[In response to audience] So you make a choice but you never fully live that choice because maybe you should have lived the other one. So then, “Well, I chose this but maybe today’s the day I should go back and do that one. But no maybe I should wait until tomorrow and give it a little bit longer chance before I change my mind and go back to this one….” [laughter] I mean, we just make ourselves so tangled up. It’s awful.

We want some resolution very quickly and, like you said, we make a choice but we don’t really live the choice because “maybe it’s the wrong one. Or maybe I really want to do this.” But then unless we really engage with the choice we never fully experience it, so we never really know if it’s the right choice. So you’ve made a choice, but actually you’re still back at point zero, sitting on the fence. You’re a turkey sitting on the fence and Thanksgiving is coming…. And you’re exposed, sitting on that fence.

But doubt is very uncomfortable. We (want) quick resolution, make a quick decision and then keep doubting it afterwards.

Because like you said, there’s a lack of self-confidence. It’s like, okay, I’m thinking about this, I’m making this decision as best as I possibly can now. I’m going to live it fully. And basically, I don’t have a lot of control. And nothing to lose. So, as long as I keep my ethical discipline, and as long as I learn from the situation, it’s not going to turn out entirely awful.

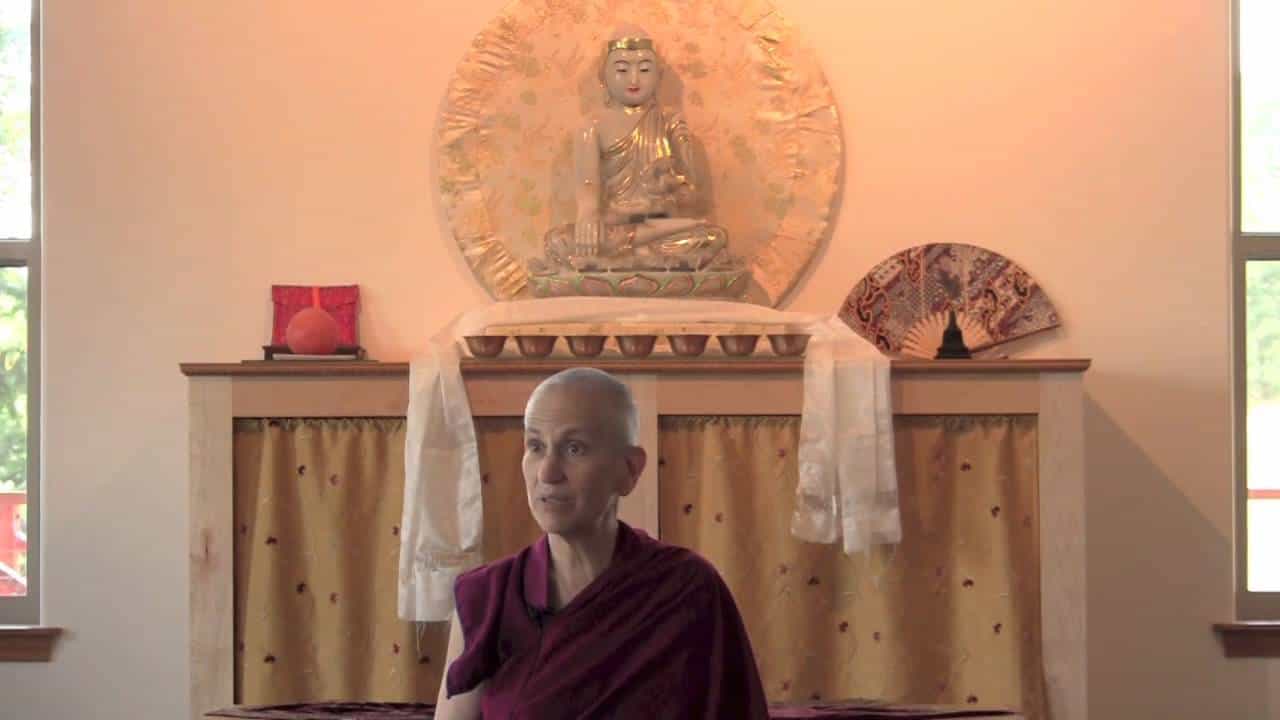

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.