Eight worldly concerns

Part of a series of short Bodhisattva's Breakfast Corner talks on Langri Tangpa's Eight Verses of Thought Transformation.

- Questioning and investigating what society says is normal and acceptable

- Examining our priorities

- The importance of meditating on these and looking at our own experience

Without these practices being defiled by the stains of the eight worldly concerns

And by perceiving all phenomena as illusory

I will practice, without grasping, to release all beings

From the bondage of the disturbing, unsubdued mind and karma.

This verse is about doing the practice of all the preceding verses with a pure motivation, and with the awareness that the practice is empty of true existence.

It says “Without these practices being defiled by the stains of the eight worldly concerns.” The eight worldly concerns. I’ll talk about them again. I think I told you that Zopa Rinpoche, my first teacher, he would teach a whole course, one month, on the eight worldly concerns. And after some years, I really appreciated that he did that, because it really teaches you the difference between what is Dharma practice and what isn’t. So it always surprises me when I meet people who haven’t had that ingrained in them at the very beginning.

The basic idea with the eight worldly concerns is that our mind is taken up only with the happiness of this life. (The word “only” is important.) In other words, we’re not thinking about future lives. We’re not thinking about our actions bringing a result in future lives. We’re not thinking about the disadvantages of samsara and wanting to attain liberation. We’re not thinking about other sentient beings being caught in cyclic existence, and wanting to benefit them. We’re thinking about my happiness now.

Which is what most of us think about. Isn’t it? If we’re honest? From morning to night. We wake up in the morning. What’s the first thought? Is it “I want to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings”? Is it there’s a cyclone coming into west Bengal, and two decades ago a similar cyclone killed some incredible number of people. Is that what we’re thinking about? There’s a cyclone in India, and it’s really dangerous, and they have to get all these people out, and these people live in thatched houses, and their house is going to be torn up by the cyclone, and their boats, and their whole livelihood and everything is going to be gone. Is that what we wake up thinking about? No. We wake up thinking about, “Oh, somebody put me on the chore list and I don’t want to do that chore.” Or, “Someone criticized me for some small thing, and why can’t they leave me alone?” Or, “I hope they’re making brownies for dessert today. Oh, they’re not. The dessert table is empty.”

It’s true, isn’t it? Most of what we’re thinking about is our own immediate happiness. Maybe we’ll extend it to next year. Maybe to old age. I’ll save some money for my old age. But some people can’t even think that far ahead. They don’t plan for old age. The appearance of this life is too strong, and I’ve got to have my happiness now, and I’ll spend my money, I’ll do what I want to do, and that’s it.

This is the mind of the eight worldly concerns. It’s all caught up in attachment to possessions and money, and then being dismayed when we don’t have them, or lose them.

This is a big thing in society today. Isn’t it? What people worry about. Even if you have money, you worry about not having money. So the mind is never peaceful regarding that. If we have the latest digital things, we always want more and better when the new ones come out. There’s always attachment to getting these things, upset when we can’t. That’s one pair of the eight.

The second pair of the eight is attachment to praise and aversion to blame. We want wonderful, ego-pleasing words. People to say nice things. “You do such a good job. The way you vacuum that floor is prestigious.” And we don’t want to hear any criticism, like, “You missed the corners when you vacuumed the floor.”

I’m using simple, everyday examples. But it goes all the way up the line. Right now the White House and Congress are involved in a battle, and one’s criticizing the other, and nobody likes it. Same thing.

The third pair is attachment to having a good reputation and aversion to a bad one. The difference between this and the “praise and blame” one is praise and blame is with people you know on an individual basis. Somebody says, “I love you, you’re the best thing since sliced bread, I can’t live without you….” Or the opposite, which is “Get out of here. I never want to see you again.” That’s the praise and blame one. Or, “You do everything wrong.”

The reputation one is our image in a broad group of society. If you’re in school, your image among all your classmates. If you have a job, your image in the whole company. If you have a hobby, your image in the swim club, or the bonzai club, or the whatever-your-hobby-is club. How you play football.

Look at the attachment to reputation that exists in the sports fields now.

And aversion to notoriety, having a bad reputation in a group of people.

That’s the third of the four pairs.

The fourth of the four pairs is attachment to nice sensory things. See nice things, hear nice sounds, smell nice things, taste nice tastes, nice tactile sensations. And we don’t want any unpleasant sensory sensations.

These attachments and aversions are called normal life in society. Aren’t they? This is normal. People don’t like being criticized, they like being praised. They want the temperature in the room the way they want it. This is called very normal, understandable behavior in society.

Being a Dharma practitioner means we question what is normal and acceptable in society, and we investigate. Are these things really as important as society says they are? And what are the results of being attached to the four (possessions, praise, good reputation, and nice sensory experiences), and what are the effects of being upset when I don’t get them and instead get their opposites. What kind of behavior do I do to get four and to get away from the other four? Really looking at karma, at our ethical conduct. Looking at our motivations. Looking even in this life if those four sets of attachments and aversions really bring happiness or not.

Society says yes it brings happiness. But really check up if it does. We’re attached to our ideas, we hammer away at our idea. Everybody finally capitulates because they’re so tired of listening to us. And then are we happy? Does that guarantee everlasting happiness? No. People capitulate, but then they resent us.

Or somebody criticizes us, and we’re mad: “You can’t criticize me, you can’t talk to me like that, I’m out of here, you’re out of here, forget it.” And you stamp out. Then are you happy? Does the relationship go better after you do that? No.

This involves really a lot of meditation, really looking at our own experience. This is not a theoretical meditation where you have all sorts of refutations with four tenet systems and complicated language that’s difficult to understand. This is just spend some time looking at your life. Spend some time looking at the lives of the people around you. And just look. What are the results when I get hung up in craving these four or being upset about getting their opposites? What’s the result? What’s the result now? What’s going to be the result in future lives, according to the actions that I do and the motivations I have?

This is not saying we’re good people or we’re bad people. It’s not “Oh I’m attached to the eight worldly concerns, what a bad person I am.” It’s not that. It’s just looking at our life and saying, “I want to be happy.” And what is really going to bring happiness in the long term? Society tells me that’s going to bring happiness. Let me investigate it and see if that’s true. Or my own spontaneous mental states tell me that’s going to be happy. “If I get a smoothie with exactly the kind of fruit I like in it, I’m going to be happy.” And then you check. I made that smoothie. I painted that painting. I got the deck that I wanted. Whatever it is. I got that. Now, where’s my everlasting bliss? It’s still nowhere. Or, “I conquered all my enemies, I refused to go for questioning in front of Congress, I refused to testify, I refuse to do my job because people criticize me, I can’t stand this.” Then, just look at your own experience. Are you happy?

This is a very down-to-earth kind of meditation. And if you do it repeatedly, it really helps you to set your priorities well. And it helps you to become more mindful and attentive of what kind of motivations arise in your mind. What kind of thoughts arise in your mind. And that kind of mindfulness, awareness of what our thoughts and emotions are, is really, really helpful for helping us figure out what to practice and what to abandon, which is helpful for having a peaceful life now, having a good rebirth, progressing on the path to full awakening.

Take a few weeks, a few months. Do this meditation very regularly, and see what happens.

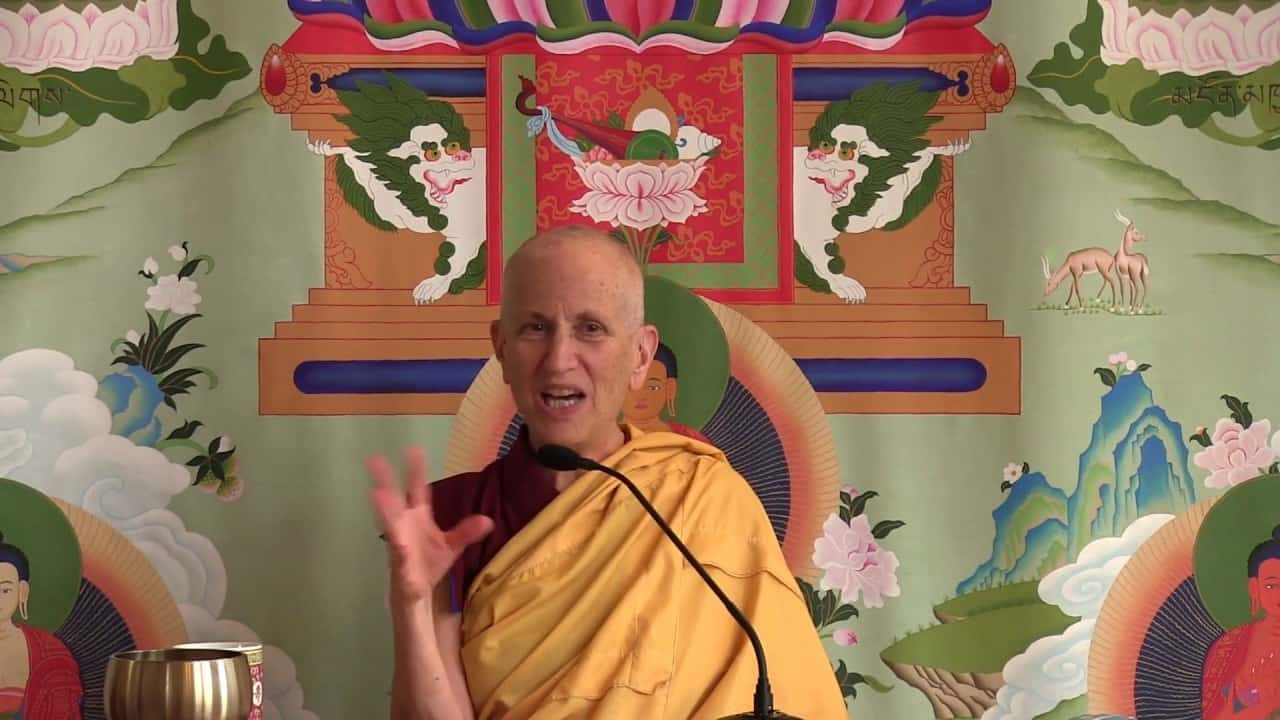

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.