Verse 20: The evil spirits that devour others

Part of a series of talks on Gems of Wisdom, a poem by the Seventh Dalai Lama.

- People need leadership, but not domination

- Those who abuse power destroy others, devour them

- What is considered abuse depends on perspective

Gems of Wisdom: Verse 20 (download)

Here’s verse 20:

What evil spirits devour others even when they’re not hungry?

People in power who abuse those under them and consider them as worthless as grass.

True, isn’t it? “What evil spirits devour others even when they’re not hungry?” People, even though they’re not hungry, they consume others with their powers. They destroy others, they eat them up by abusing their power. It’s interesting because this was written by the Seventh Dalai Lama who himself had a position of great power. He was the political leader of the Tibetans.

By the way, the Dalai Lama is not head of the Gelugpa Tradition. Many people make that mistake. The Ganden Tripa is the head. The Dalai Lama is, you could say, in general the religious leader of Tibet, and the political leader…. Or at least he was, but he resigned a few years ago. Now Tibet has a Prime Minister and they’re running the government that way. It’s interesting because it’s the only group of people I know on the planet where the leader wants less power and the people want him to stay in power. You know? Because before he resigned they were saying, “No, don’t resign. Don’t resign.” And he saying, “But I want to, you need to be more democratic.” Quite interesting.

But the Seventh Dalai Lama, at his time, he was general ruler over Tibet. Tibetans never had a real centralized government. There were always local kings and chieftains, but he had to kind of “herd the cats” so that they kind of stayed together in some way. And of course the people in the Himalayan areas in Mongolia also respected him a lot. And also he held a lot of sway in the Manchu court in Beijing at that time. He was somebody who knew very well about what could happen if somebody abuses power, and so I think made great efforts not to do that.

We can really see in any kind of institutional structure that people need leadership, but they don’t need domination. And sometimes the line between leadership and dictatorship (or domination) is not so clear. How do you lead without controlling, but then on the other hand a leader has to have a certain amount of control. So it’s really quite a sticky area.

George—who was visiting us this weekend—he’s the head of the central office for FPMT and I was asking him a little bit about his strategy and he said that he sees his position as keeping everybody else happy. And he told the people that are working in the office, “I trust you to do your job and I’m not going to breathe down your back.” And so far that’s working quite well. People are really rising to the occasion and doing their jobs. So if you have the right people underneath who, when you trust them, are trustworthy, it works in a really nice way. If you have somebody who’s not so trustworthy, who’s lazy and exiting right and exiting left, then that kind of thing isn’t going to work. So it’s difficult, you know, to be a leader in that way.

But definitely abusing power is a whole other ball game. That’s when people threaten other people. For example, threaten to fire them, threaten to do this, threaten to do that. When people use their power to physically abuse others, or sexually abuse others, or emotionally abuse others. Those kinds of things people are becoming much more aware of in our society. But it is like an evil spirit who isn’t hungry, but devours people, when power is abused.

And it’s so difficult to say where is that line where there’s an abuse of power? Because for one person what somebody is doing may be an abuse of power, but for another person it’s not. And this is what gets sticky sometimes in organizations. And it happens in Dharma centers, too. Any organizations where you have human beings, this kind of stuff can potentially happen. But it’s really hard to say because people have different definitions of what it is. So how do you actually discern where is that line? And what you label something?

There’s a lot of discussion, actually, in the press about this whole thing. People have very different definitions. And this can sometimes be the source of a lot of confusion, a lot of difficulty.

Also, for example, like with the Tibetans. The way they have their organizational structure is very different from a Western organizational structure. What we might consider an abuse of power they would not, because it’s perfectly legit in the way they run things. In Tibetan society—or at least in the monasteries—you usually have somebody at the top and everybody else [under them]. You see this structure in Dharma centers a lot. The teacher and then everybody [else below]. And everybody only listens to the teacher. They’ll only do something if the teacher tells them to do it. Thus, they never learn to work cooperatively. And then when the teacher’s not there they don’t know what to do. But it’s also an open door for the teacher to abuse power because people will not work together, they’ll only listen to the teacher. So that opens the door for the teacher to say this, that, the other thing, that could be really really dangerous. So that’s why students need to learn how to work together and cooperate with each other.

[In response to audience] That’s a good point, that people would trust the teacher, assuming that they practice a lot and the teachers would guide people wisely. So sometimes you have teachers who aren’t practicing so well, and then you have an abuse of power. That can happen.

Or sometimes you can have a teacher who is not practicing well but still has a very strong ethic and good leadership qualities. And you can have teachers who practice well but because they grew up in a different society what constitutes abuse is very very different.

[In response to audience] First of all you can have people—the students—who don’t trust the teacher, and then, in the name of democracy, take the organization and take Dharma really in a very steep decline, because they think their wisdom is better than the teacher’s. But you can also have students who imbue the teacher with so much power that the students enable the teacher to abuse power. Or students that just keep quiet about things that aren’t so good.

It’s really, it’s quite a sticky area. But it’s something that is good for us to be aware of, and to be aware of cultural issues. And everybody has a responsibility. And how people act out their responsibility is going to be different in different cultures and different situations. But yes, I think very definitely everybody has a responsibility.

What came out in the 1990s especially, when there was a lot of abuse of power in Buddhist centers in the West, is that very often the students enabled the whole thing to happen. Especially if you invite a teacher from another culture and they’re alone, and they may or may not speak the language of the host country. They have no support. And they have none of their peers who know what’s going on. And yet Dharma centers don’t want to bring a whole bunch of monastics over together because it’s quite costly. But then you have the teacher alone, without his peers, and without a support structure too. So that can be dangerous.

You get all sorts of different combinations in this whole thing. The moral of the story is to practice well. And be responsible. So followers have responsibilities. Leaders have responsibilities. And to keep on top of this kind of thing. Motivation, of course, is the central thing.

[In response to audience] And it’s true that people in the lower levels can abuse power, too. That’s a good point.

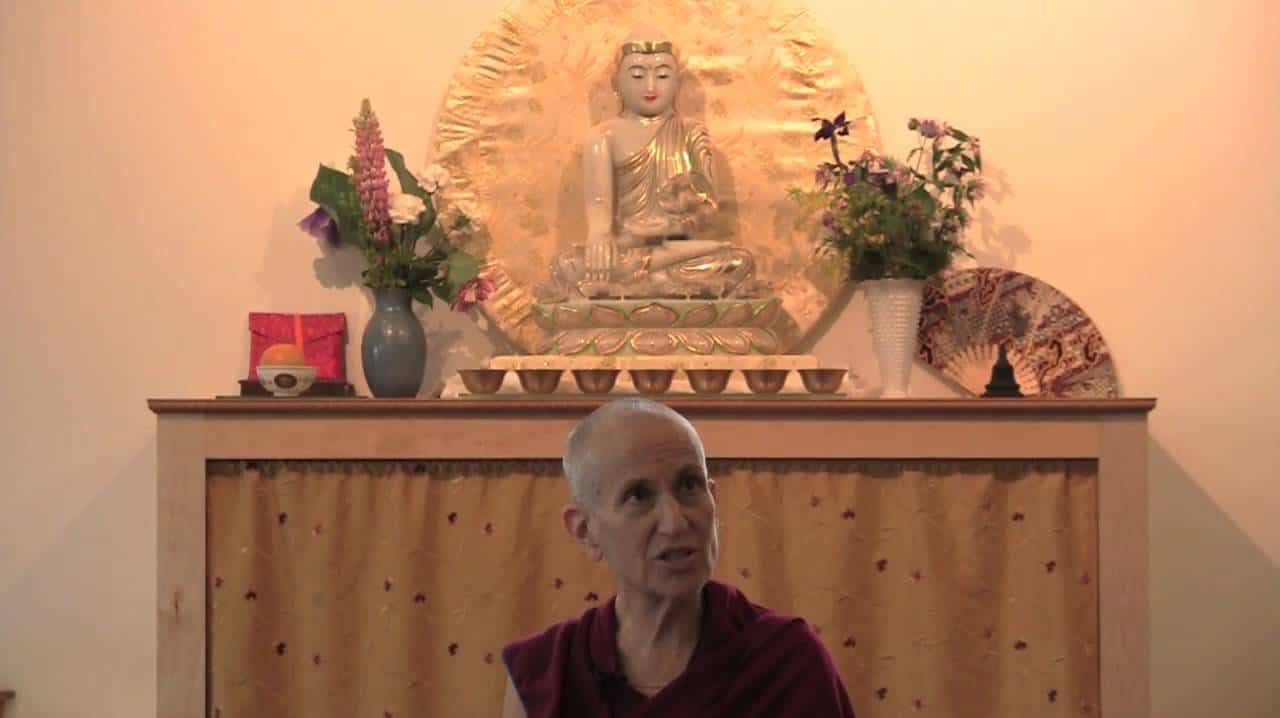

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.