Relying on the Dharma

Part of a series of teachings on the text The Essence of a Human Life: Words of Advice for Lay Practitioners by Je Rinpoche (Lama Tsongkhapa).

- How our friends and relatives cannot help us at the time of death

- How no one can protect us from physical and mental pain or suffering

- Relying on the Dharma to get us through difficult and painful situations

The Essence of a Human Life: Relying on the Dharma (download)

On to the next verse, which says:

To conclude: you are born alone, die alone,

friends and relations are therefore unreliable,

Dharma alone is the supreme reliance.

What more can I add to that? He said it so succinctly and so true. We are born alone. Even if you have twins or triplets, even if you live your whole life surrounded by other living beings who promise never to abandon you, can they fulfill that promise? We’re born alone, we die alone. Even if everybody dies together at one time, we all have our own experience. Nobody else really shares our experience.

When he says we’re “born alone, die alone, friends and relations are therefore unreliable,” it’s really true, isn’t it? I mean, they’re lovely people and they promise all sorts of things, but can they fulfill those promises? When they themselves are impermanent, when they themselves are under the influence of afflictions and karma, how can they fulfill those promises? When sentient beings who have no control over their minds, whose karma is ripening here, there, everywhere, people whose afflictions come and go, and come and go…. They mean well, but what can they really do in the long term? Or even in the short term. Can they really protect us from suffering?

We might have some big dog or big something that says, “I’m going to protect you from anybody who tries to hurt you,” but that living being too, very easily, can be injured and they die. How can they protect us from suffering when they can’t even prevent their own body from injury and death.

And people promising to protect us from mental pain: “I’m going to love you forever. I’m going to support you forever.” Do they? I mean, they’re under the influence of afflictions. Their minds go up and down. They like us, they get mad at us. They want to always be with us, then they want never to be with us.

All these things are controlled by other conditions, they’re not self-generated things that we have control over all by ourselves. The mind changes. The karma changes. The only real protection in all of this is our own Dharma practice, because who knows what we’ll wind up experiencing in this life?

When you read people’s biographies it’s very interesting…. Some people start out, really horrible things when they’re young, and by the time they’re old, very nice life. Other people start out, wonderful life when they’re young, and then as they age, negative karma ripens and they have a lot of pain and suffering. I think of people who were part of the aristocracy in China before the Communist Revolution and the Cultural Revolution, and who wound up being imprisoned, and beaten, and tortured simply because they were from the upper classes. And nobody saw this coming. Nobody could have said, when somebody was born, “You know, you are going to be imprisoned by the time you’re 40 years old, and tortured.” Or in Mexico how they kidnap people. Nobody expects that to happen. Yet these kinds of things happen. Of course, nobody thinks, “I’m going to get cancer, or heart disease, or kidney disease,” yet people do.

When these things happen it’s only the Dharma that is going to be able to help us get through the experience. Our worldly mind that craves the eight worldly concerns doesn’t know how to deal with these situations at all, it just freaks out. The only thing that’s really reliable is our Dharma practice. And to have that Dharma practice we have to hear teachings, reflect on them, meditate on them, integrate them into our minds. If we do that, then these things are not situations of great suffering. We have something that we can do to transform them.

His Holiness, at the teachings I attended in June, he told the story of one monk that he met in 1959 in Amdo who was from Tashi Kyil Monastery. This monk was a very good scholar. He was the tutor of the incarnation of Jamyang Zhépa, so he must have been quite a scholar and practitioner. In 1958 the communist Chinese came in, they arrested about 200 monks and they executed 15 or 20 of them, and among them was this monk, I don’t know his name, he’s just the tutor of Jamyang Zhépa’s incarnation. When they took him out to the execution place, he asked them if he could pray before they shot him, and he chanted the verse from Lama Chopa on the tonglen, the taking-and-giving practice. And then they shot him. And His Holiness said, “This is somebody who is a real practitioner.” You could tell by what he thought to do before he was killed.

How do you get to be a practitioner like that monk? By starting where we are now and learning, practicing, and constantly familiarizing ourselves with these kinds of teachings. Then we gain the ability to transform adversity so it actually becomes an aid on the path.

His Holiness also commented that he heard from somebody who’d read about the history of Nalanda Monastic University in India getting destroyed in the 13th century, and that there were a number of monks who were being slaughtered but who seemed not to have any fear, again because they’re practitioners. And His Holiness commented, “It would be mistaken to say they didn’t have any pain, because without pain you can’t practice fortitude.” But they responded to the painful situation with a mind that was integrated with the Dharma, so they didn’t experience fear and anger.

It’s actually possible to train our minds in those ways. It is possible. We just have to do it. Nobody else can do it for us. It’s very true.

To conclude: you are born alone, die alone,

friends and relations are therefore unreliable,

Dharma alone is the supreme reliance.

Yet in our lives when we don’t understand the power of the Dharma, the Dharma being the one true thing we can rely on, then we take refuge in human beings who don’t have the ability to protect us. Just as we don’t have the ability to protect them, do we? We can have a lot of compassion for others, but when their karma is strong, what can we do to overcome their karma? We can plant seeds, but those seeds are going to take a while to ripen. Similar with us.

Audience: I think one of the things I’m trying to learn in the Dharma is that its profundity has to do with thought transformation, not about changing the external circumstance so that things start going well. I’ve had a lot of struggle because I want to practice the Dharma, then everything out there is going to get better, when it’s not. When it’s about what’s going to get better in here. So I’m still shifting that expectation of making things pleasant out there.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: I spoke about it yesterday how we pray to the Buddha to change the external situation without realizing that the very thing that needs to be changed is our mind. We’ve all had the experience of being in a wonderful external situation and being miserable. Have you had that experience? Being in a beautiful environment with people you like, and you’re miserable. It’s not about changing the outside world. It’s changing what’s in here (inside).

[In response to audience] You’re saying one of the signs by which you can measure your practice and your progress is to see how much you’re ready to accept the external situation and work on your mind instead of always trying to change everything on the outside.

Of course, if you can change the external situation, do it, if it’s easy to. But don’t spend all your life energy trying to change the external situation, because you’re never going to get it to what you want it to be, and no other person is ever going to be what you want them to be. So let’s get into changing this one (ourselves), making this one who we want him or her to be.

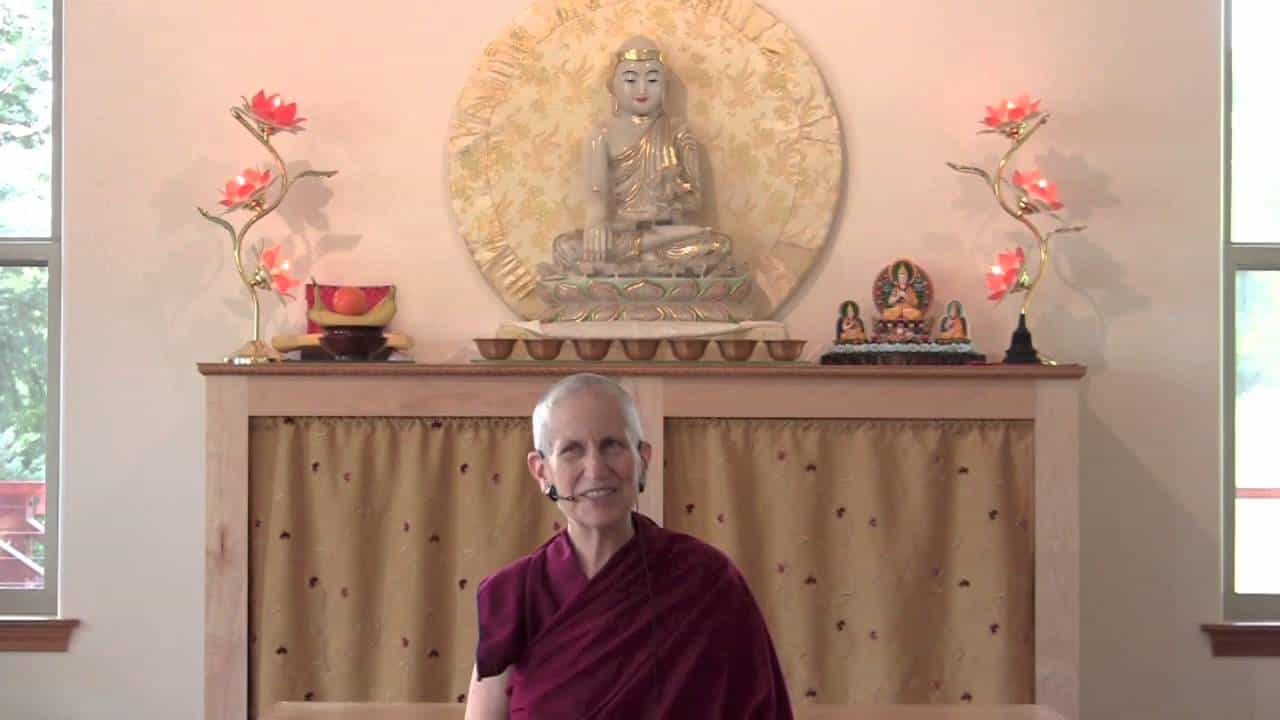

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.