Tonglen and social problems

- Avoiding the need for praise or reputation in doing the taking-and giving practice

- What it means to practice direction and indirectly

- Maintaining an open heart while doing this meditation

- Bringing the practice to the social problems in the world

- Talking about the wrong views that cause so much strife in the world

In short, I will offer directly and indirectly

Every benefit and happiness to all beings, my mothers

I will practice in secret taking upon myself

All their harmful actions and sufferings.

Practicing the taking and giving meditation that I talked about yesterday, where with compassion we imagine taking on the various kinds of dukkha that sentient beings have, and using that to destroy our own self-centeredness and self-grasping. And then with love giving them our body, possessions, and merit.

It says to do this practice “in secret.” That means we keep our mouth closed. We don’t go around saying, “I’m doing this very high practice of taking and giving. I’m taking all your suffering. I’m giving you all my happiness. I am this great Mahayana bodhisattva practitioner.” No. It means we do our practice and we keep quiet about it. Because the moment we start talking, why are we talking about it? We want reputation. We want offerings. We want fame. That just contaminates our practice.

If you’re in a discussion group with some other Dharma practitioners, or you’re talking to your teacher, yes, of course you can talk about it. But not just casually to other people, or to the guests, or whatever. That’s the point about “in secret.”

Another thing that’s quite good about this meditation. We were talking about “directly” and “indirectly.” By practicing it, it increases our love and compassion so that when there’s an actual opportunity to be of benefit to somebody, we step forward, we don’t hesitate, because we’ve already familiarized with the idea of taking on harm and giving our body, possessions, and merit. That’s the direct way. This helps us be ready to give directly and help directly.

It also is indirect in that when we aren’t able to help anybody directly—we don’t know what to do, we can’t reach them, what we do doesn’t really have much effect because they’re in another part of the world—then we maintain an open heart by doing this meditation. We don’t just shut people out and say, “Well, it’s their problem, I can’t deal with it, it’s on the other side of the world. Forget it.” We do this meditation because that keeps our heart open and connected to those people, which is very, very important, because at some point we may actually be able to give some direct benefit. And in any case, the indirect connection, I think, is quite important. People still receive some benefit from it, and we receive some benefit from it.

Now, the tricky thing is, we don’t use this meditation as an excuse to avoid giving direct benefit. in other words, when it’s possible to say something or do something, we don’t chicken out and say, “Well, I’ll just do the taking and giving meditation.”

I was thinking…. Because the last few weeks we’ve had three terrorist attacks on places of worship. First there was the attack that killed 50 people in New Zealand, against two mosques. Then there was the attack against three churches and three hotels in Sri Lanka. We don’t know how many people that killed, because the Sri Lankan government keeps changing the number. Then a few days ago we had another attack in California against a synagogue. Three different houses of worship being attacked across the world in a very short period of time.

This is something we need to talk about, and we need to speak about, we can’t just do the taking and giving meditation, taking on the suffering of the people who died, even taking on the suffering of the terrorists who committed these actions. But we need to definitely, first of all, call it terrorism. It is domestic terrorism, whether it’s against a religion, or racial group, or whatever. I was reading that the black churches…. Now that this kind of thing is happening in America, they’re talking about having security at churches. And the black churches are going, “You’re just now talking about having security at your houses of worship? We’ve had to do that for 150 years.”

It doesn’t matter who it’s against, what religion or race, this kind of behavior, in the context of our country, is definitely domestic terrorism. In the context of the world it’s terrorism in general. And we need to call it out as such, and have law enforcement involved with it as such. In reading some of the comments about the synagogue attack, one person was saying that it’s very important, again, to keep guns out of the hands of people with mental illness because that person said it was a mentally ill person who did this. That that person has got to be mentally ill.

Now, I completely agree, we’ve got to keep guns out of the hands of people who are mentally ill. And I agree that to think that killing strangers is going to make you happy indicates some kind of mental illness. But society also sanctions killing people you don’t know, thinking that it will make you happy. And what is it that sanctions that? It’s views. Wrong views. “These people are like this.” Whether we do it as a military action or we do it as terrorism, it’s the same thing of objectifying another group of people, where we don’t know the individuals, and then thinking that killing them will somehow make us happy. This is where the Buddha’s famous statement, that “Anger never resolves anger, only loving-kindness does” comes in. We have to call it out for what it is.

There is “mental illness.” But the definition of mental illness can be very, very broad, too, because somebody who is a terrorist like this, is it really mental illness? Or is it wrong views? If that person didn’t have access to these kinds of hateful views, and didn’t have an online community that is supporting them in these views, would that person still act in the same way, even if they had a mental illness? They may not. And what about people who don’t have an observable mental illness, who come in contact with all these kinds of views–whether it’s the views that make you attack Muslims in New Zealand or Christians in Sri Lanka, or Jews in California…. Or we had a case here over a year ago where the Sufi temple was defaced and attacked in Spokane. It doesn’t matter who it is. But the kind of communities that build up, either by direct association or online, that support these kinds of views, that make somebody else the source of our pain, and thus the right behavior is to terminate them.

I think this is something we need to talk about, and we need to do something about. There’s a lot of discussion about social media being a source of a lot of these kinds of views. And how do we control social media, which was created with this optimistic framework that it’s going to link all these people who could never get in touch with each other? And now it’s producing this monster.

There’s a lot to discuss here. I don’t claim to have answers about how to regulate social media. You need external regulations, but you really need regulations on people’s minds, and how do you do that? In some way, I think, so much of it comes back to education and what we teach young people. And what we encourage in our discussions with other people. And what comments we let slide, what comments we call out, just in casual interactions with other people. How do we do that in a kind way, in a respectful way, but to still say that kind of thought, that kind of remark, is not helpful to world peace. And it’s not helpful to somebody’s own happiness themselves.

I’m just raising this topic. I don’t have clear answers to it. But I know it’s something that we need to deal with, and we need to talk about. As a country, as a society.

Audience: …mentally ill, it’s sort of like, it seems like an excuse. The Buddha said everyone is mentally ill. Which is true. If we’re not mentally ill right now, we’re very susceptible to becoming mentally ill. That’s another argument. And then also, what is considered mentally ill is defined by society. Wanting to kill other human beings. If it’s against one group, it’s okay. Like if you’re a soldier or a police officer, psychologists are not going to say you’re mentally ill. But if suddenly you want to kill another group of people that is not sanctioned by society as being worthy of being killed, then suddenly you’re mentally ill. To look at that category more broadly and see people as being affected by their environment. It’s not like one day they’re mentally ill and the next day they’re not. It’s very much like in process. And there are these wrong views floating around, then anybody can be susceptible. We call these people brainwashed. But do we call them mentally ill?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: They’ve been radicalized. Are they really mentally ill?

What I’m getting at is we can’t now blame mentally ill people. Because terrorism is not the problem of mentally ill people. It’s a problem of people who are holding wrong views, and are very biased and prejudiced.

Like you said, from the Buddhist viewpoint, holding those kinds of views is mental illness. But none of us can say that we’re totally sane from a Buddhist viewpoint. Because as long as we have ignorance, anger, and attachment, there’s mental illness in us, too.

We can do the taking and giving meditation in these situations, but we also need to see it as a social problem and to act. Especially to think, what to do with social media.

It’s making me think about the scientist who invented the atom bomb. It was this wonderful, exciting science, and they were going to come up with so many fantastic things that would really improve mankind, and then it got used to kill people.

The same thing with the tech people. Not thinking of how what they create could be used, and then we wind up with a monster.

The same thing now is being talked about in terms of artificial intelligence. Because the face identification doesn’t always do it correctly, and you could wind up arresting and targeting a lot of people who are innocent.

We need to think about our inventions. The same thing when it comes to genetic research. Are we going to have designer babies? Are we going to start euthanizing people who have certain genes, because we associate those genes with certain characteristics—whether they really have those genes are related to the characteristics is another matter. But people can believe that and then harm other people because of it.

A lot of deep thought as a society and as groups of people.

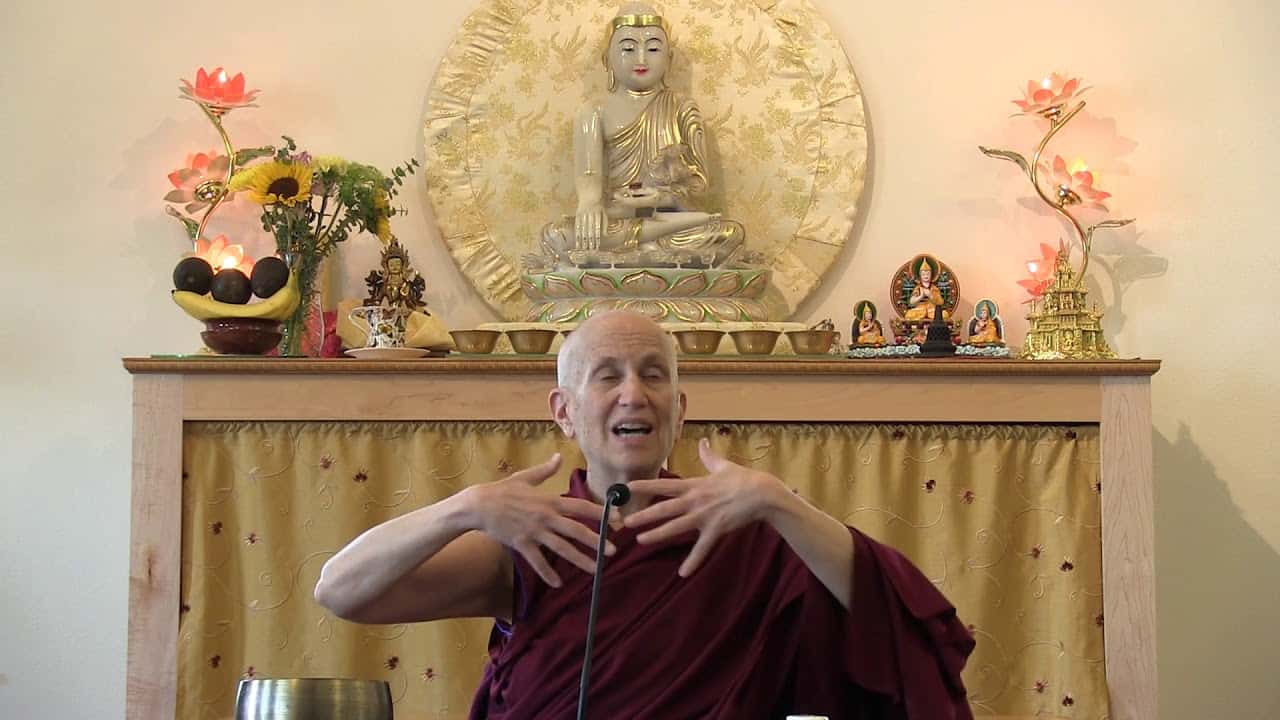

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.