Auxiliary bodhisattva ethical restraints 21-25

The text turns to training the mind on the stages of the path of advanced level practitioners. Part of a series of teachings on the Gomchen Lamrim by Gomchen Ngawang Drakpa. Visit Gomchen Lamrim Study Guide for a full list of contemplation points for the series.

- Developing the proper motivation for gathering disciples

- Dispelling the three types of laziness

- Avoiding spending time idly talking and joking

- Seeking out the conditions and teachings for the development of serenity

- Abandoning the five hindrances to concentration

96 Gomchen Lamrim: Auxiliary Bodhisattva Ethical Restraints No. 21-25 (download)

Introduction

Welcome everybody. And, to the people online, we’re starting a week-long retreat on Tara, so I’m just going to make a few comments about that, because I always call a retreat a time of taking a vacation with the Buddha.

Taking a week out for going on vacation with Tara is really nice because Tara is a really nice person to be with; she doesn’t insult you. She doesn’t pick at your faults. But the problem is that you can’t pick at her faults either, because she’s a Buddha. What it means is that everything that comes up in our meditation we’re responsible for, and we can’t blame it on the Dharma, or on the Buddha, or on Tara, or on anything else. But it’s a wonderful opportunity to have some time apart from our usual hectic lives, to really look inside and develop our good qualities. So, tomorrow we’ll get into the Tara sadhana, and I’ll give some explanation on that, and also on the eight dangers that come with the Tara practice, which I always like to talk about, because they’re so juicy.

But tonight, what we’re doing is a continuation of a series of talks I’ve been giving for over a year now on the Gomchen lamrim. We’re in the section on the lamrim of the bodhisattva precepts. I’ve been talking about the auxiliary bodhisattva precepts, and even though some of you don’t have these precepts, or you haven’t heard the previous year’s teachings (which are all online by the way if you want to follow them), I think what we’ll be talking about tonight will be completely understandable, and will be helpful if you haven’t listened to everything that’s come before.

Joyous effort

Last time, we finished the precept in accord with the perfection of fortitude. So, we’re starting the ones about the perfection of joyous effort. In the auxiliary bodhisattva precepts, they’re divided according to the six perfections, and the precepts are to abandon certain activities that prevent us from generating the six perfections: generosity, ethical conduct, fortitude, joyous effort, meditative stability and wisdom. We’re on the fourth one of joyous effort. There are three precepts here.

21. Gathering a circle of friends or disciples because of your desire for respect or profit.

It starts with number twenty-one of the auxiliary precepts. These are things to abandon:

Gathering a circle of friends or disciples because of your desire for respect or profit.

Joyous effort is taking delight in creating virtue, but if we do what looks like virtue, such as gathering a circle of friends or disciples, but our motivation is crooked, meaning that we want to gather people because we want respect or profit, then it’s really interfering with our Dharma practice. This precept is specifically against the tendency to become proud or arrogant because of having students, or because of knowing the Dharma, such that people will become impressed with you, and like you, and follow you around, and you will have a whole circle of groupies.

That’s a really blatant illustration—someone who just wants a circle of groupies, little puppies following them around saying, “You’re a buddha; you’re a buddha.” And you see examples of this. Not that everybody who’s a teacher who has that kind of disciples or has a bad motivation, but some of them are definitely looking. Because if you have a group of people who regard you as the teacher, you get some status, then of course you’re hoping all the students that look at you as the teacher will tell other people how wonderful you are: “Oh, so and so is such a good teacher. I want to take the retreat. This course that they led, this, this, this.” They tell all their friends. And then, of course, you become more well known, and you begin to think that you’re somebody.

That mind that begins to think that we’re somebody important in the Dharma world, that we have some special ability to be a teacher, becomes a big hindrance to practice. Because if we’re a big shot, we don’t think we can learn much from anybody else. We’re already so knowledgeable, so “Why should I go to this person’s teachings or that person’s teachings because anyway I know just as much as them or I’m as highly ranked as them”? Whether we are or not doesn’t matter. We think we are, and that inhibits our ability to learn from other people. And it completely distorts our Dharma motivation, such that our Dharma practice becomes the eight worldly concerns.

Instead of creating virtue, we’re just focused on the eight worldly concerns, seeking reputation. Also, when it says profit, it means offerings. So, if you’re teaching or giving talks, then you start to get the feeling of “Look at what I have and who I am, and look at all these emails they send me, and how adoring they are. Look at the cards they send me saying how much they benefited from my talks and retreats. We have them all around, and we’re like, we’re pretty good, aren’t we? Yes, almost as good as our own teachers.” If you start thinking that, then you’re really in trouble. Plus, all these people who think that we’re so wonderful give us gifts. They make dana offerings, monetary offerings; they give us food. They give us socks. They give you shoes, too. Then you become a little bit uppity, and you tell them what kind of shoes you want: “I don’t want those shoes. I want brand shoes,” or “I want boots. My winter boots are junky. I want really nice winter boots.”

So, you start collecting. People want to give you things. They want to give you maybe a Rolex watch. This is why, at the Abbey, we don’t wear watches. Because in the Tibetan community many people wear watches as jewelry, and it impresses people if you have a very nice gold Rolex watch. Watches are a status symbol in the Tibetan community. And, certain kinds of shoes—the kind of shoes that everybody wears, gym shoes with the different colors and the thick soles—are a big status symbol. And then, certain kinds of backpacks. It’s not crummy backpacks that you’ve been using for fifteen years, but new backpacks with lots of pockets that are kind of jazzy. Those are status symbols. So, this is talking about wanting offerings from your benefactors, your students, or whomever gives you those things that increases your status and like that.

That mind is not a Dharma mind, and it’s completely deceptive. It not only cheats the students, but it cheats us. Because if we think we’re already such hot stuff, then we can’t learn from anybody. The Tibetans have a saying that “The lush meadows grow at the bottom of the valley, not at the top of the mountain.” The top of the mountain is bare and jagged rock. So, we should always try and have a good motivation when we are teaching or giving talks or whatever.

22. Not dispelling three types of laziness.

Number twenty-two is:

Not dispelling three types of laziness:

- Sloth.

- Attraction to distracting activities.

- Self-pity and discouragement.

Let’s look at those and see why they interrupt our joyous effort, which means taking delight in virtue.

Sloth

Sloth is: “I’m really tired. I can’t meditate now. I’m tired. I’ll do it later. I was up last night talking to my friends, so I overslept this morning. Now there’s no time to practice.” Or it might be: “Tonight, there’s a really good show on TV, so there’s no time to practice. I’ve worked hard all week. On the weekend I think I’ll just take it easy and relax. I’ve set out a whole thing of Dharma study I was going to do on the weekend, but that was on Monday, now it’s Friday. I’m tired, I’m sleep deprived.” You know that mind. It’s a very convincing one for why we can’t study and practice. “I’m so tired, I worked so hard.” So, there’s that one.

Attraction to distracting activities

The second one is being extremely busy with worldly activities. This one actually in society makes you fantastic. This makes you the excellent worker that everybody wants to have because you are driven to overwork, to complete the project, to get it done, and be the leader. Then, after you’ve done that you have your hobbies. You’ve got to excel at your hobbies, and you have to go to all the latest movies, because everybody in the office is talking about the latest movies, so you have to go to them. Otherwise, who are you going to be if you don’t watch all the latest movies? So, we are the busiest of the busy. We always have appointments. Our schedule is full. It’s called “getting a life,” as in when you aren’t busy all the time people say, “Why don’t you get a life?” They mean that we should be doing lots of things, to write a lot of stuff on our Facebook page, so that we have a good image and we’re the busiest of the busy doing samsaric activities that don’t help our Dharma practice at all but are basically distractions from creating virtue.

All these worldly activities are the things that worldly people will compliment you on and praise you about: “Oh, you work at this company, and you get a promotion.” And it was because you worked 12-hour days, and you got the promotion. And everybody is envious because you are doing so well at your job. Plus, you’re watching all the movies, and you’re working out at the gym, and you’re going on all these exotic vacations. You are the model of somebody who is with it! You know what I mean? We all have our own version of that depending on your surroundings, and who you want to impress, and what activities you like to do. One person is traveling all the time with their work, another person is growing bonsai plants; another person is knitting. Another person is bowling, and we all have our own thing that we want to be best at so that we can project this good image.

You make appointments to see your friends, and the first thing that happens when you go to the restaurant to see your friends, is everybody takes out their Smartphone and puts it on the table. Everybody has their Smartphone on the table, and you check your Smartphone, and if you have a lot of things coming in on your Smartphone that take you away from the conversation with the friends, then you’re somebody who’s really important. Look at all these people who are texting you! Half of them are wanting to sell you something but never mind. You take the call; you check the text. Meanwhile, you’re with your friends. You’re doing this to make appointments to be with other friends, and then when you are with your other friends, you also take out your Smartphone and put it on the table and look at it a lot, and text other people to make appointments to be with them. It’s crazy, isn’t it? And, we feel like, “Wow, I’m so popular. I’m doing something. I have all these appointments! I’m so busy.”

That’s the whole thing. Why can’t you go on retreat? Why can’t you go to teachings? Why can’t you read the book? Why can’t you have a daily meditation practice? It’s because “I’m so busy.” Saying “I’m busy” means “Don’t ask me any more questions. Don’t ask me what I’m busy doing, because then I might have to tell you that I’m actually just lying around doing nothing, folding the laundry or whatever.” But “I’m busy” is the ultimate reason or excuse for why you can’t do Dharma. We’re always too busy, aren’t we? But what are we doing that makes us too busy doing most—usually worldly—activities? There are so many things we have to do, especially if it’s June. There’s weddings. You’ve got to go to all the weddings. Then, a few months later, you go to all the baby showers. Anyway, you’ve got the idea.

Self-pity and discouragement

To review, the three types of laziness are sloth, being busy doing worldly activities, and now self-pity and discouragement. This is, “Gee, I have to visualize White Tara? Come on. White Tara? Come on. White Tara, where are you? I can’t do it. I’m trying to visualize and she’s just not coming. Maybe she went on vacation with somebody else, not with me. I just can’t visualize anyway. I’m hopeless. I just can’t visualize. It’s not my way.” But if I ask, “What kind of pizza do you like,” do you have a visualization of the kind of pizza you like best? You have that visualization just like that, don’t you? If I say, “Think of the person that you’re romantically attracted to,” they’re in your mind, a perfect visualization. So, we can visualize, but we just can’t visualize the Buddha very well. Why? It’s because of habit. We’re much more familiar with objects of romance or people that we’re attached to—could be a mother or children or our pets as well. We can visualize them very easily because of habit. Pizza? That’s a good habit, instant visualization.

We just have to create a new habit to visualize the Buddha, or any other thing that we use to discourage ourselves in the practice. “Enlightenment: caring about all sentient beings more than myself? Forget it. I can’t do that. Anyway, I don’t want to care about other sentient beings more than myself. Because if I do, I’ll suffer. I don’t want to suffer. So, let them go to some other person who’s a Buddha. I can’t become a Buddha. Buddhas have to give their body for the benefit of sentient beings. I don’t want to give my body to anybody. The goal’s too high; the path is too difficult, and anyway, I’m incapable.” It’s the whole thing of putting ourselves down, like: “Oh okay, I know I have a problem with attachment; I know I have a problem with anger, but I really can’t do anything. I’m just attached to that person or those people. I’m just attached. That’s the way it is. I can’t do anything about it. Anyway, they want me to be attached to them and I want to be attached to them. What’s wrong with being attached anyway? Why does Buddha say attachment is a hindrance? I think attachment’s great; it makes me feel good, except when I don’t get along with that person! But never mind that.”

Or anger: “I just have a temper, that’s all. You’ve just got to learn to deal with it. I can’t do anything about it. My parents are like that. My grandparents are like that. We’re all hot-headed, so don’t ask me to change.” It’s this whole thing of discouraging ourselves, telling ourselves we can’t change before we’ve even started. Or, it’s the self-pity mind: “Oh, oh! I tried to meditate on the antidote to anger, but nobody loves me! They don’t love me, so I’m angry at them, and I feel left out. All the people I’m attached to don’t reciprocate it. Everybody else has so many friends, but I don’t. They all pick on me. Ever since I was in kindergarten, and even before that, I was the kid that got bullied. I was the kid who wasn’t in the popular group. And it’s still like this now; at the Dharma center nobody loves me either. I’m sure they say every Buddha loves everybody, but I don’t think he loves me because I’m just unlovable.”

The mind of self-pity and discouragement is not humility. We confuse humility with discouragement and self-pity. Actually, self-pity and discouragement are a form of arrogance. “Because I’m special, I’m the worst one, I’m the most incapable one” is actually a form of arrogance. You can see how with all these three kinds of laziness, we can develop identities that are attached. It’s similar with the one from the previous precept: “I’m this great teacher who gives wonderful talks, who has all these people who love them and say I’m wonderful.” Or it’s: “I’m the person who, you know, I just sleep a lot”; “I’m the person who’s the busiest of the busy because I have so many important worldly things to do that make me successful.” Or maybe it’s: “I’m the person who’s totally incapable. I can’t visualize White Tara. I can’t visualize Purple Tara. I can only visualize pizza.” Tara sitting on an open lotus flower is difficult. Tara sitting on a pizza is possible. On an open lotus flower on top of which is a pizza with mushroom and extra cheese. On top of that sits Tara radiant.” If we visualize that then we can get it. “Her right hand in the gesture of generosity, giving hot fudge sundaes. The left hand in the mudra of refuge. The two fingers, Google and Bing. The three fingers upwards are my Smartphone, my tablet, and my computer. She has eyes in the palms of her hands and then her feet. Three eyes on her face so she’s able to look at Instagram and Tumblr, all at the same time.”

We develop whole identities based on these things, and then it becomes a huge obstacle to our Dharma practice. Because instead of having enthusiasm for virtue, and feeling delighted, and happy, and rejoicing when we create virtue, we just shoot ourselves in the foot and don’t even try. That’s a great loss, because it takes a lot of good karma to have a precious human life. It is very rare and difficult to have this opportunity, and then to have it and waste it is really a tragedy. So, joyous effort is very important.

23. With attachment, spending time Idly talking and joking.

Then we move on to:

With attachment, spending time idly talking and joking.

How much time do we spend idly talking and joking, just messing around, playing around, and things like that? We’re not really doing anything meaningful. This doesn’t mean that all of our conversations with people have to be deep, intense Dharma discussions. That certainly won’t work. This is spending a lot of time, like: “I like to chat just because when I chat, I can tell really good stories. I can tell jokes. I monopolize the conversation. And I’ve been at the Abbey the longest, so I know all the ins and outs, and I can tell you everything about the Abbey, so I can dominate the conversation.” Whatever it is, it’s just spending a lot of time liking to hear ourselves talk. We say “talk” because they didn’t have texting. They spoke and all that kind of stuff at the time of the Buddha, too. This really interferes, because we spend so much time, so much time, doing this.

24. Not seeking the means to develop concentration, such as proper Instructions and the right conditions necessary to do so, and not practicing the instructions once you have received them.

Now we’ll go on to meditative stability. There are three precepts there. The first one is:

Not seeking the means to develop concentration, such as proper instructions and the right conditions necessary to do so and not practicing the instructions once you have received them.

Here we transgress this due to lethargy—we don’t feel like it; we’re too tired—or pride: “I know it already. I don’t need to seek instructions on concentration. I know how to develop concentration already.” As an effect of either of those minds of lethargy or of arrogance, we don’t seek out the instructions. We don’t go to teachings to learn how to concentrate. Instead, we consider ourselves expert meditators, and we think that we’re just going to sit down and develop concentration all by ourselves. Or maybe we’ve heard a little bit of teaching on it, and we think, “Well, that’s enough. I’ll be able to develop samadhi with a little bit of teaching.” Or we receive teachings but then when we sit down to meditate, we don’t practice them because we’re really enjoying our distractions a lot. You sit down to meditate, and you go, “There’s White Tara,” but then it changes to, “Oh, White Tara reminds me of a friend that I have. This friend and I, we used to go to the beach every summer, that was really nice. And lotuses remind me of my trip when I went to Burma.” We do a lot of meditation on everything that has to do with me.

The thing to do here is to receive teachings on how to develop concentration. We should try and practice them, and if we are intent on developing serenity or samatha, we definitely need to seek the right conditions to do so. They say if you don’t have all the right conditions, your efforts won’t bring you all the way to serenity. You may increase your concentration somewhat, but to actually go through the nine stages that culminate in serenity, we need special conditions. For example, we need to be in a very quiet place without a lot of sounds, not with highways, not with kids, and television, and neighbors, and our phone buzzing or beeping or vibrating. You need to have very good ethical conduct; you need to learn to be content, to be easily satisfied, and that’s really difficult. If we’re going to do retreat with the intention of developing serenity, we should choose a place that has these qualities and train ourselves beforehand, so that we’re easily contented, easily satisfied. And we need to have good ethical conduct so that we’re not disturbed by a lot of regret and remorse, so that we don’t break a lot of precepts and so on.

Lots of times, when people start the Dharma, they really want to focus on developing serenity as a main thing, and that’s a wonderful aspiration to have. My teachers have always encouraged us first to get a good overview of the path—to understand how the path works, how it functions. They encourage developing experience in mind training, in the ability to restrain ourselves from unethical actions, and the ability to restrain ourselves from following attachment, anger and all the other afflictions. Because, if we don’t have some familiarity with the antidote to the afflictions, then when we sit down to meditate, they just overwhelm our mind, and we don’t know what to do. Whereas if we’ve practiced the thought training teachings and the lamrim teachings, then when we’re trying to meditate to develop concentration, if attachment and clinging comes up, we know, “Okay, have to meditate on impermanence, and the disadvantages of cyclic existence.” If anger comes up, we know we have to meditate on fortitude and on loving kindness. We know the antidotes, and are able to apply them, so that we can return to the object of our concentration, the object of our meditation. If we aren’t familiar with the antidotes then we just have one affliction after the other, and it becomes very difficult to develop concentration. I’m not saying don’t try. I’m saying, especially if you have work and a family and you’re active, to just accept that you can improve your concentration, but it’s going to be difficult to develop full serenity within the external conditions in which you live. Or it will be difficult if you lack the kind of prerequisite training and knowing the instructions and so on.

From my experience in talking with people who have done long retreats on serenity, some people are quite successful, and some people may be successful in generating some concentration, but they don’t really have the Buddhist worldview. What they choose to do after the retreat indicates to me that maybe they didn’t understand. They didn’t really have the Buddhist worldview and understand the path to awakening. I always think that the more preparation we can have, the better—in everything we do.

So, practice serenity and samatha as much as you can, but be realistic. If you have a good understanding of what samsara is and how disadvantageous it is, and you have an understanding of what the path is, what’s needed to attain liberation and awakening, then all your practice is geared towards your ultimate spiritual aim, and you’re not going to get sidetracked by different experiences you may have in meditation. And you’ll also be able to deal with all the things that come up when you are trying to develop serenity. Because, when you’re really doing intense retreat on that, all sorts of stuff comes up.

One of my friends did a three-year retreat. Some of you may have been here when she came to EML (Exploring Monastic Life), and she was telling us about her experience. She said everything you’ve ever done in your life comes up in your retreat. You find yourself chanting commercial jingles that you heard when you were a kid. I remember specifically she said, “And there you are, trying to meditate, and all of a sudden out of seemingly nowhere ‘the ants are marching one by one’ comes into your mind,” or whatever it is. All that kind of distraction comes in and also all sorts of previous experiences that you’ve had. If you have things that you haven’t worked out psychologically, those things are going to come up in the middle of your retreat, and you’re going to have to work with them.

I think the more we can prepare for that kind of retreat, the easier the retreat is going to be. Whereas if we have very little preparation and we don’t have the right circumstances, not much will change. I heard this story: one friend was talking with a Tibetan lama, and another student came in who had just finished a three-year retreat and started talking about what they had done in meditation in the three-year retreat, and everything, this and that and the other thing. Then, when that person left, the lama made some remark to the effect of “Three years of meditation, but the mind is still the same.” That is sad.

The more preparation we have the better. This is a way to encourage you in your daily practice. Because how do you get that preparation? It’s through having a consistent daily practice, and being very patient, because it takes a long time to work on our mind. It takes a long time to overcome bad habits, old habits. We’re not going to get rid of them by Tuesday or even maybe Wednesday—fifty years plus Wednesday or fifty lifetimes plus Wednesday. It’s always better to have really a long-term vision in our practice instead of one that is looking for quick, jazzy results.

Like I said, it’s not meant to discourage you; it’s meant to encourage you in terms of making proper preparation. It’s kind of like if you’re going to the DMV to take a driver’s test, you better practice driving beforehand. Don’t go in thinking, “Oh, I’ve watched other people drive, I know how to drive,” because that’s not going to work at the DMV. You knock into the other cars, and then they ask you to parallel park—oh!

25. Not abandoning the five hindrances to meditative stabilization: sensual desire, malice, lethargy and sleep, restlessness and regret, and doubt.

Then twenty-five:

Not abandoning the five hindrances to meditative stabilization, sensual desire, malice, lethargy and sleep, restlessness and regret, and doubt.

There are different sets of five hindrances. There’s another set when you’re talking about Maitreya’s teachings on how to develop samatha. These five are the ones that are found in the sutras that are common in the Pali and Sanskrit traditions.

Sensual desire

I’ll talk a little bit about these because we’re starting a meditation retreat so we’re going to encounter these. The first is sensual desire. We are beings in the desire realm. We love to see beautiful things, hear beautiful sounds, smell nice things, taste good food, and have nice, pleasant physical sensations. We have a lot of sensual desire. You’re meditating and lunch comes up, and then you’re wondering what is for lunch. Your boyfriend or girlfriend come up, your new sports equipment comes up, your children and your parents come up. We’re filled with desire. We want things. You’re thinking of the boat you want to buy, or the Caribbean cruise that you want to go on, or the rock climbing you want to do, or whatever your thing is. We’re filled with desire for new exciting experiences and sensual sensations. This comes up in meditation, doesn’t it? It’s right there.

You’re no exception when this stuff comes up. Don’t think everybody else in the room has samadhi, and you’re the only one thinking about sex, food, money and rock and roll. Everybody’s doing it. Maybe not at the exact same moment as you are, but at some time or another in the retreat, this is going on. We’re all dealing with the same stuff. So, what do we do when sensual desire comes up in our mind? What’s the antidote? One of the antidotes is to think about the ugliness of the object. You’re sitting there having sexual fantasies and you dissect the body—mentally dissect, please, not actually. You mentally dissect the body of the person you’re lusting after. Peel away their skin: what’s under their skin? Take out their eyeballs and put them on the table, and their ears, and then take their hair and spread it out. What is it they say: “Your eyes are like diamonds, your teeth are like pearls.” Take all their pearly teeth, and what’s so beautiful about their teeth? And examine their skin, and what’s under the skin? If that doesn’t cure your desire…

We look at the ugliness of the object, or we look at the disadvantages of attachment to that object. Where’s the attachment going to take me? I’m dreaming about a new improved paycheck with more money coming in and what I’m going to do with it. I’m dreaming about the promotion I’m going to get so that I can get that new paycheck, or whatever it is. And then you think, “Well okay, is that only going to bring advantages? Or, what’s going to happen? What’s going to happen if I have that paycheck and then get all those possessions?”

The more possessions you have, the more suffering you have when they break. Remember, before you had a computer, you never suffered from computer hell. Now we suffer from computer hell because our computer breaks. And you know how it deletes the files—the most important one that you need that day? It just deletes it for who knows what reason. Once you have a car, you have car hell because your car breaks down and then you have to pay money to get it fixed. It always breaks down when it’s inconvenient because anyway there are no convenient times for your car to break. And your car is going to break. As soon as you have a car, it’s guaranteed it’s going to break.

Our chipper caught on fire. As soon as you have a chipper you know you’re going to have the chipper that broke. It’s going to break. We had to replace our hot water heater. So, as soon as you have hot water, you know you’re going to have a hot water heater that doesn’t work. The more you have, the more problems you’re going to have. And then you also have the privilege of working more hours and becoming more exhausted to make more money to buy all those things. And then you really have problems because you get the latest thing, like the latest Smartphone, and then they release a new one in another year. Your phone is obsolete, and all your friends have the new phone. You have the old phone. Just think about the difficulties.

We dream of having this beautiful house. We had some college students come up a few weeks ago, and during lunch one of the guys said he’d really love to get a good job and make a lot of money. I asked why, and his wife said, “Oh, so we could live in a nice house.” I said, “Really? You want to live in a nice house? Because there’s all sorts of problems you have when you live in a nice house.” Like I said, the more things you have, the more things are going to break. Then, of course, if you have a really nice house in a really nice neighborhood, you need a burglar alarm. What’s going to happen when you have a burglar alarm? It’s going to go off at times when you don’t want it to go off. Like when I stay at someone’s house, and I get up early and open the front door, not realizing that they have a burglar alarm, and then suddenly the alarm is blaring. Or your kids open a window in the middle of the night, and it sets off the burglar alarm. Or maybe the burglar alarm just feels like going off anyway—they have their own personalities.

Just think a little bit about this stuff, and it really helps to lessen the desire. When we’re wanting status, when we’re wanting praise and a good reputation, when we’re wanting people to approve of us, what I find works very well is to ask myself, “What good is that going to do me?”

I got a new social status. How’s that going to advance the things that are really meaningful for me and my life? Okay, I get praise, and I get fame, and I get more social status. That means I get a better obituary when I die. How is that better obituary going to benefit me? I’m already going to be born in another realm. I’ll be more famous; more people will come to my funeral. I have a better bigger funeral than you have. Well, who cares when you’re in a lower realm what kind of funeral you had in your previous life? And how is anybody’s praise ever going to be meaningful to us? We say, “People will approve of me and praise me, and I’ll feel good about myself,” but that’s a set-up because then when they criticize and disapprove of what we’re doing, we feel awful about ourselves.

What good is somebody’s praise going to do us? You think you want to be famous and then it’s a hassle. Look at the people who are famous now. They get written about; their whole private lives are public. Every little thing about their lives is printed and dissected in the media. I wouldn’t want to have that kind of fame.

They say if you’re a bodhisattva then being famous can be good because more people might come to your teachings and you could influence them. But I think you really have to be a highly developed bodhisattva to endure a lot of fame. Really, look at His Holiness—he can’t just go outside where he lives and walk down the street. The really famous high lamas can’t just walk down the street. Everybody knows them, and comes and wants a blessing. Also, they’re trapped by this whole social code of status of high lamas and who must go visit whom. If you’re a very high lama you don’t go visit the lower lamas; they have to come and visit you. There’s this whole social thing.

Sometimes you can’t just be an ordinary, anonymous person, when everywhere you go, you’re put in a role due to the fame. I think it’s quite burdensome. I think of Ivanka Trump and her husband. They get so much publicity and so much fame, and you look at them, and they are the epitome of what every American wants to be: rich, famous, gorgeous, young, and rich. They have kids, they have fame, they have power—they have everything. I wouldn’t want to be them, not for a million dollars or even two million or five million. I would not like to look like Ivanka Trump. To me, she looks very plastic. Everything is so perfect about the way she looks. She looks like a plastic doll. And then in every picture that people take of you, you have to be perfectly posed and present a perfect image; no thank you.

You get trapped by all of that. It’s a complete prison, a total prison. When you want to be famous, really think about what famous people have to go through. Because also if you’re famous, everybody’s going to criticize you. As soon as you have power and fame, what do you have: criticism! Sometimes if you really want to practice the Dharma, being an ordinary, innocuous person makes it much easier, much easier. So, to work with sensual desire, think of the disadvantages of things, think about the ugly aspect, think about “If I got this, what good would it really do me?” We usually realize it wouldn’t do me any good.

Malice

Then malice is the next one—malice or ill will. This is when somebody hurt us, somebody harmed us, they cheated us, they deceived us, they betrayed our trust, and we want revenge. Of course, we’re much too cultured and polite to say, “We want to hurt somebody and make them suffer!” But that’s our intention; there’s ill will in the mind. “Somebody hurt me, and I want to hurt them back for their benefit. It’s so they’ll have a taste of their own medicine. They’ll know how I feel, and they’ll come crawling on their hands and knees to apologize to me.” Forget it! Malice is extremely painful. If you’re trying to meditate, you can see why it’s an obstruction to gaining concentration, because all you’re doing is meditating on how much you hate somebody. You’re meditating on how much you want to cause harm to them, how much you’re jealous of them. It’s a very, very unhappy mind.

The antidote to that is fortitude. In a case where somebody has harmed you, to learn to endure suffering without taking it personally. Also, we work to develop loving-kindness and compassion for people; instead of having ill will and malice, you have a kind attitude towards them. And if you can spend some time meditating on kindness every day then it really transforms your relationships, because how you see people change.

We have a retreat for the next week, so every day in some of the time when you’re doing silent meditation, contemplate the kindness of others. And don’t focus on people you’re attached to—that’s easy but not helpful because then you just get more attached to them. Think of the kindness of the people who have helped you that you’re not attached to, maybe different mentors, or people who are good role models, or examples for you—maybe people who tutored you. And then from there go on to strangers: the people who make the roads, grow the food, make your clothes, and all these kinds of things that enable us to survive in the world.

Then when you get really good at that, go on to think about the kindness of the people who have harmed you. Think how, by harming you, they’ve woken you up out of your complacent stupor, and pointed out to you your afflictions, and your need to work on certain qualities, certain aspects of yourself. Because without the people who say things that we don’t like, we would never see our faults so we would never change. We are always saying, “I want to improve; I want to improve.” Somebody’s telling us how to improve. Don’t pay attention to the tone of their voice. Don’t pay attention to their vocabulary. Pay attention to what they’re telling you and see if it’s true or not. If it’s true then work on that aspect of yourself, because you’ll be happier if you do.

Questions & Answers

Audience: Can you say a little bit about how the twenty-first one relates to joyous effort?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): That’s the one about gathering a circle of disciples because of your desire for respect or profit; so, you’re asking how does that relate to joyous effort? Because it looks like you’re creating virtue, but you’re not, because your motivation is completely crap, so there’s no delight in virtue, and there’s just delight in the eight worldly concerns. You spend your time with this corrupt motivation looking like you’re practicing Dharma, but there’s no delight in virtue.

Audience: It’s so easy to have the wrong motivation. That’s part of the problem. You think you’re doing great because you’re measuring the success of your practice by the external situation, not by what’s happening internally. So, it’d be really easy to be seduced by that internally for a long time.

VTC: Yes, that’s why people who criticize us are some of the people who are kindest to us. If we’re stuck in that, the person who points out our phony bologna is helping us tremendously—because we’re not even aware that we’re doing it.

Audience: How do you know when you’re ready to do a serenity retreat? Will your teacher tell you? Or, if you’ve been practicing for a certain number of years, it just comes up?

VTC: Well, there’s this chart, and if you practice for four years and three months and two days…[laughter] No, it’s going to be really individual because people have different dispositions, different interests, different inclinations. So, it’s going to be something that from your side: you’re very interested in doing it, and you’ve done preparation and from your teacher’s side they think that you’ve done the sufficient preparation and have the right external conditions to be able to do the retreat. I would add, too, that they know that if you develop serenity, you’ll use it properly to continue to advance on the path and won’t just seek serenity as “This is the end point. Once I get this, then I’m satisfied.” Because that’s not liberation.

Audience: You mentioned that sometimes you can see that people have done some concentration retreat and there’s some kind of signs that you can see that they haven’t really gone in a direction that the meditation would hopefully lead them to. What are some of those indicators?

VTC: They complain; they get angry a lot. They’re very dissatisfied and want more and better. There’s a lot of doubt in their practice. There’s not a lot of conviction in the practice, or there’s a lot of enchantment with having a good reputation—that kind of attachment, too.

Audience: Why is serenity not liberation? Because it sounds pretty good.

VTC: When it comes to all the levels of concentration, serenity is just the first one. After serenity there’s the four dhyanas or the four jhanas, and then above them the four formless meditative absorptions. So why aren’t they liberation even though they sound really peaceful? First of all, they haven’t eliminated the afflictions from the root. What’s happened is, due to the power of the concentration the coarse afflictions have temporarily been suppressed so that they don’t come up and interrupt your meditations. You can stay in concentration single-pointedly for a long time. Those coarse afflictions have been suppressed, but they have not been uprooted. When the karma to be in that kind of state is consumed, then you’re back to where you were before—because the afflictions have not been completely forever removed.

What would be a good example? You have knapweed, so you just pick off the flower at the top or you just step on it and crush it, or you pull it but you don’t get the root, so it’s going to come back again when the right circumstances are there. Just because you have single pointedness in concentration, it does not mean you have the wisdom that is necessary to completely cut off the afflictions and the other obscurations. If you’re a human being and you attain serenity or the levels higher than that, if you don’t dedicate properly and you get stuck in just enjoying that bliss, then you get reborn in those realms in your next life, and you enjoy the bliss of the meditation. But after that, the karma for those rebirths runs out, then—kerplunk—you’re back in the desire realm and maybe even in the lower realms again. They say that actually we’ve all been there and done that. Everything in samsara we’ve all been there and done that before. So, they say now when in a precious human life we should really focus on attaining liberation or awakening.

Here’s just a little exercise for the retreatants, and also the people online can practice this, too. When you go to bed in the evening you might like to try this and see if it works for you. Imagine White Tara or the Buddha on your pillow and put your head in their lap and think that very gentle light is flowing into you as you go to sleep. Go to sleep with the idea of not just “I’m so exhausted, thank God, I get to lie down,” but instead with the thought that “I’m going to rest my body and mind so that in the morning I’m bright and can practice well.” Then, when you get up in the morning, try and make this your first thought, as soon as you remember it,

Today, as much as possible, I’m not going to harm anybody by what I do or say or even think about them.

Today, as much as possible, I want to be of benefit to others in whatever big or small way I can be.

Today, I will hold the bodhicitta, that altruistic intention for full awakening for the benefit of all beings.

I’ll hold that very dear and precious to my heart and try and increase that throughout the day.

If you start the day with that kind of motivation, it really affects how you are during the whole day. And then periodically throughout the day, come back to your motivation.

Next week, we will start with lethargy and sleep and progress to agitation and regret and then go on to doubt. These are all things that afflict us in our meditation.

Contemplation points

Venerable Chodron continued the commentary on the bodhisattva ethical code. Consider them one by one, in light of the commentary given. For each, consider the following:

- In what situations have you seen yourself act this way in the past or under what conditions might it be easy to act this way in the future (it might help to consider how you’ve seen this negativity in the world)? Consider some of the examples Venerable shared.

- Which of the ten non-virtues is the precept helping you to restrain from committing?

- What are some of the exceptions to the precept and why?

- Which of the six perfections is the precept eliminating obstacles to and how?

- What are the antidotes that can be applied when you are tempted to act contrary to the precept?

- Why is this precept so important to the bodhisattva path? How does breaking it harm yourself and others? How does keeping it benefit yourself and others?

- Resolve to be mindful of the precept in your daily life.

Precepts covered this week:

To eliminate obstacles to the far-reaching practice of joyous effort, abandon:

- Auxiliary Precept #21: Gathering a circle of friends or disciples because of your desire for respect or profit.

- Auxiliary Precept #22: Not dispelling the three types of laziness (sloth, attraction to destructive actions, and self-pity and discouragement).

- Auxiliary Precept #23: With attachment, spending time idly talking and joking.

To eliminate obstacles to the far-reaching practice of meditative stabilization, abandon:

- Auxiliary Precept #24: Not seeking the means to develop concentration, such as proper instructions and the right conditions necessary to do so. Not practicing the instructions once you have received them.

- Auxiliary Precept #25: Not abandoning the five obscurations which hinder meditative stabilization: excitement and regret, harmful thought, sleep and dullness, desire, and doubt.

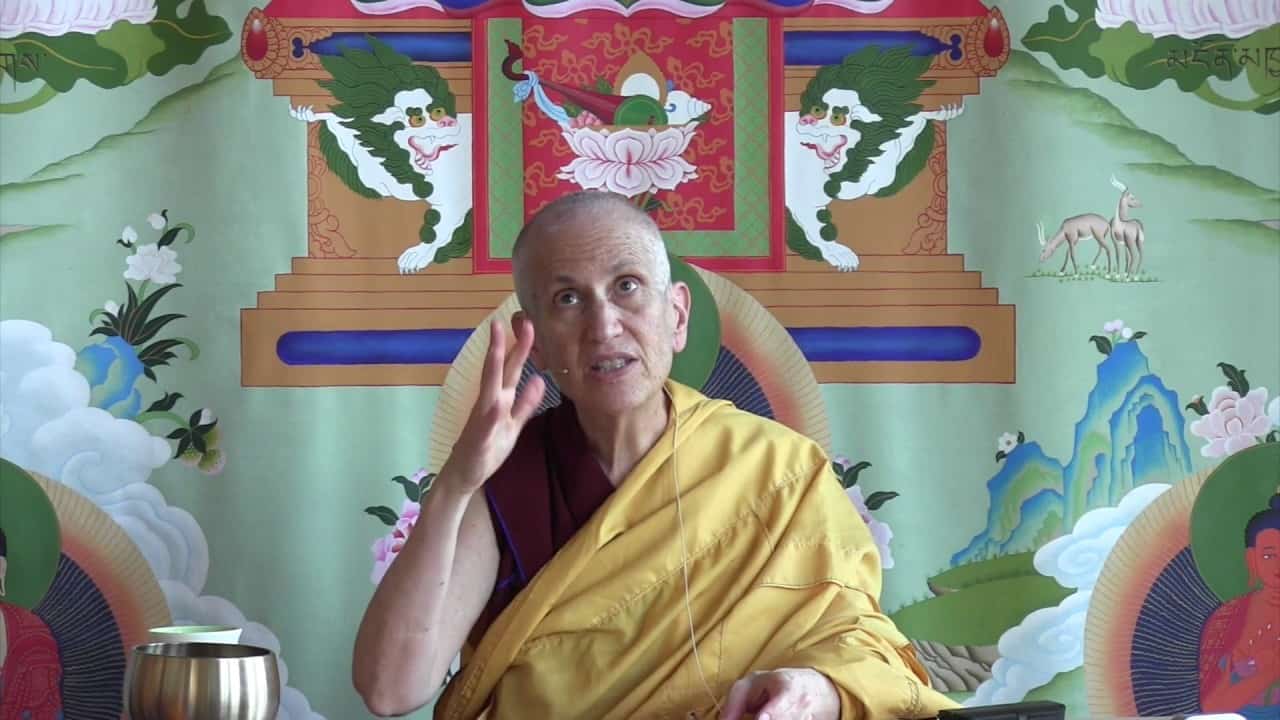

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.