Buddhist precepts regarding food

Part of a series of short talks about the meaning and purpose of the food offering prayers that are recited daily at Sravasti Abbey.

- The Buddhist perspective on fasting

- How practitioners keep Buddhist precepts related to food

This time I’d like to talk a little bit about precepts regarding food and about fasting.

About fasting. The Buddha did not advocate any kind of really harsh ascetic practices, he was completely against those. He had tried them himself when he spent six years meditating with his five companions on the other side of the river from Bodh Gaya and he got so thin that when he touched his belly button he could feel his spine. So of course, when the body is basically emaciated and starving, it’s going to affect the clarity of the mind as well, so the Buddha didn’t advocate any kind of extreme austerity like that.

Of course, Buddhists themselves may decide, let’s say, to go on a juice fast or whatever, but that’s something aside from Buddhist practice. If they do decide to do that then they need to really check up on how it’s affecting their mind, and as Lama Yeshe used to say, not go on some kind of ascetic trip.

The kind of asceticism that the Buddha did advocate would be, for example, we (the monastics and the anagarikas) have a precept not to eat after midday and before dawn of the next day. This precept has several reasons behind it. Some traditions follow that precept quite literally and other ones don’t.

Living on alms

The reasons behind it were, first, because at that time the sangha was mendicant, so people would go in the towns with their alms bowl. They did not beg. Begging means you ask for food. They did not beg. They gathered alms. Alms means that they walk with their bowl, they stood there, if people wanted to give something, fine, if people didn’t they went on to the next house. But they did not beg for food. So it isn’t a “begging bowl,” it’s an alms bowl. There’s a difference. Language means a lot here.

Because they were dependent on alms they had to be considerate of the needs of the lay people. If they went on alms morning, noon, and night they would be on alms quite a bit of time during the day and would hardly be able to meditate because you have to go into the village, collect your alms, go back, eat them, and by that time it’s probably almost time to walk in and collect some more for lunch, and walk back and eat… So it takes some time for the monastics.

Then second, it’s not very considerate for the lay people because those who do want to offer alms would be cooking all day. So many of our precepts are made because lay people said, “Look, this isn’t very convenient for us.” And they objected to different things, and so the Buddha made a precept about that.

Third is that if you eat a heavy meal in the evening often your mind is quite dull, it makes you groggy and sleepy. So because we want to have an alert mind for meditation we don’t want to eat a heavy meal in the evening.

Also, another reason, is that before the Buddha made this precept there were monastics who would walk into town and, because it’s dark, they couldn’t see where they were going so they would fall into cesspools, they would step into people’s ka-ka, or the animal’s ka-ka. So it was unpleasant for them. And also then when they arrived at the door of the lay person, some of the people thought they were ghosts because it was dark outside and here’s this strange figure of somebody they don’t know appearing out of nowhere, maybe sometimes smelling like feces because they stepped in it on the way into town, and it would frighten the lay people.

These are the kinds of reasons behind the precept not to eat after midday and before dawn of the next day.

Culture and geography

In India that worked well. The food had a lot of substance. Also at that time the Buddha did not prohibit eating meat. Some people have bodies that need meat and so that was available to them.

And also, in terms of the time of the clock, India is almost on the equator, so after noon and then before dawn is not so long. If you do that in Sweden in the summer it’s going to be difficult, you’re going to be really hungry by the end. So I think when Buddhism goes to different cultures, different climates, different living situations, different expectations of the lay people, then these things happen to be modified.

For example, when Buddhism went to China, because it was a Mahayana tradition they were vegetarian, and so they felt that it was healthier (to keep their body healthy) to have three meals a day, so the evening meal was called “medicine meal.” In the Chinese tradition they don’t actually offer the food then, they see it as medicine. Actually, we should see our food as medicine all the time, no matter when we’re eating it. But they particularly call it medicine meal so that we remember that we’re eating it like medicine to sustain our bodies and our health so that we can practice.

Also in China what happened is a lot of the monastics moved out of the city. They didn’t want to stay in the towns and cities because there were always things going on with the government and the bureaucracy, and then they wound up getting involved in playing politics, and instead, especially practitioners from the Chan tradition, went to the mountains to meditate, and so they had to grow their own food, which is another thing that we’re not allowed to do because in ancient India they lay people were mostly farmers and again, if you’re a farmer you spend your whole day farming, there’s no time to meditate. But in the Zen (Chan) tradition when they moved into the mountains they had to grow their own food because it was too far for them to walk into the city or for the lay people to come to the monastery and offer food.

Buddhism in Tibet: there aren’t a lot of fruits and vegetables, there was mostly meat and dairy and tsampa (ground barley flour). So they had the habit of eating meat. When they came to India, His Holiness and some others are working very hard to diminish the amount of meat. And now in the monasteries they don’t eat meat in the group functions in the monasteries. In fact, His Holiness has said in Dharma Centers in the West, also, when you’re having a group function we should not serve meat. In the Abbey’s case we never eat meat at any time, so it’s clear. But I’m just explaining these things for others.

His Holiness is also trying to get people to eat more fruits and vegetables, but as we all know, eating habits die hard. So, trying, trying.

Not eating after midday

Regarding the precept about not eating after midday and before dawn of the next day there are some exceptions in the Tibetan version of the vinaya, the Mulasarvativadin version that they follow. One is if you’re ill then it’s permissible to eat in the evening. By implication, if you need to eat in order to keep good health so that you can practice, that’s possible. If you’re traveling and you’re not at a place where you can go on alms round before midday then it’s permissible to eat afterwards. If you’re caught in a storm and you’re soaking wet. They didn’t have snow there. But if you’re wet. So if there was inclement weather then you could also eat in the evening. Nowadays, because we have monasteries, we have to do physical work to do the upkeep on the buildings and the grounds. In ancient times mostly they were mendicants, and the only time they were sedentary during the Buddha’s life was during the varsa, for those three months, at which time usually there was a sponsor who offered the residence and who offered the food because the monastics didn’t go in to do pindapata (the alms round) in the summer because it involved walking and the purpose of the retreat was to not walk so much because there were so many insects on the ground. So there was usually one or more benefactors who supplied the sangha of that area with their food during that time.

Nowadays in America most of us don’t go on pindapata. I think I told you before that some of our friends at Shasta Abbey did, and at Abayaghiri did and they had to get a parade permit from the city council because it was people walking in a row. And then sometimes, people don’t know what in the world you’re doing. I went one time with Reverend Meiko and her monastics on pindapata, and we weren’t gathering food just for that day but just gathering supplies. They sent out a notice beforehand so the businesses would know what was going on. In the Zen tradition (or Chan tradition) they ring a bell so that people knew they were coming. And so people came out, a few with cooked food, but mostly with supplies. And then there was a string of lay followers behind us who, when our bowls (we carried the big bowls) would get too full they would take them and take them back to the priory or the monastery. It’s a nice tradition to do and to keep. Nowadays it needs some planning. Our Theravada friends when they go into town they usually tell their supporters beforehand and so their supporters are all lined up ready to give. If you did it really like they did in ancient India you wouldn’t have a bell, you wouldn’t tell your supporters beforehand, you would just walk in town. But if we did that here probably we would be quite hungry, and people may complain about the sangha. Also in China when they tried to go on pindapata in town people complained. They mistook them for beggars and said “we don’t want beggars here.” That could easily happen in our country, too.

Keeping the precepts

It’s up to each individual to decide how they keep the precepts about eating. I think it’s good, when you first take them, to be quite strict about it and not eat in the afternoon for as long as you can. And if at some point you have health difficulties then explain it to the Buddha, you have a little conversation with the Buddha in your meditation, request his permission to eat, and then eat mindfully and seeing the food as medicine. But if you can keep it then it’s very good. I did for the first five years of my ordination and then there began to be a lot of difficulties that occurred so I asked my teachers about it and they said to eat.

Another thing about food is when we’re eating, the monastics are supposed to stay focused on our bowl. There are a lot of etiquette precepts in our pratimoksha. You don’t chew with your mouth open, you don’t smack your lips, you don’t look around the room at what everybody else is doing, you don’t look in other people’s bowls and, “Oh, they got more than I did. Ohh, look what they did, look what they did.” You pay attention to your own bowl, not to other people’s bowls. You wash your own bowl afterwards. You treat your bowl respectfully. You don’t handle your bowl with dirty hands. Things like this.

Nyung ne

[In response to audience] Yes, they’re about to start Ramadan. The one fasting practice we do have is nyung ne. It involves the eight precepts. The eight precepts can be taken as a pratimoksha ordination for one day or they can be taken as a Mahayana ordination for one day. We do it as a Mahayana ordination. If you’re a monastic you’re not allowed just to take the pratimoksha one-day precepts because it’s a lower ordination and you already have a higher one. But to take the Mahayana precepts, that’s permissible. When you take the Mahayana precepts, actually the precept is similar here, you don’t eat after noon and before the next day. That’s the way the precept is. My teacher Zopa Rinpoche always did it where you eat one meal a day, so you eat at lunch time and you finish your meal before midday.

When you do nyung ne then you follow that practice for the first day, and you have your one meal–unless you’re doing consecutive nyung nes, in which case then you have breakfast and lunch on the eating days. You have beverages that are strained at the other time. You don’t have just a glass of milk, something that’s really rich. Or something with a lot of protein powder or yogurt or something like that. It has to be mixed with water. No fruit juice with pulp in it. Although it was very interesting when I was in Thailand they drank fruit juice with pulp. And some of them eat cheese, and candied ginger, and chocolate. They have their own way of saying what’s allowable and what’s not allowable, which I won’t go into.

But then on the second day of the nyung ne you don’t eat or drink or speak, and so that’s for the entire day. And then you break that fast the morning of the third day.

Some people may say, “Well isn’t that a bit extreme? I mean, my mother would be horrified if you went a whole day without eating and drinking, that just is not done in my culture….” But this kind of…. When you do the nyung ne, it’s done for a particular reason, and it really strengthens your spiritual practice because it turns your mind to refuge and to the meditation on Chenrezig. It’s not extreme because it’s just one day that you’re not eating and drinking, and we can manage quite well without that. And it gives us a chance to think of what it’s like for people who don’t have the choice, like we do, and aren’t doing it for a virtuous purpose, but nevertheless cannot eat and drink during one day because there’s no food or drink present.

Questions and answers

[In response to audience] If you’re keeping the precept quite strictly, which it’s good to do…. You definitely have to work with your mind, because then you start really investigating what is hunger and what is habit. And what is physical habit and what is mental/emotional habit. This thing of, like you say, “I feel deprived.” That’s kind of an emotional thing. And it especially arises, like, “Oh, they put out something really good in the afternoon for the others to eat, and I’m not eating in the afternoon, and it was all gone by the time the morning came, and I didn’t get any.” Yes? So then we’re whiny three-year-olds, and we have to remember, well, why are we keeping this precept? We’re keeping it because it was set down by the Buddha, it’s for a reason, we’re accepting that if something’s put out later that we don’t get it, and you know, we will really live. Because anyway, even if we eat three meals, I’ve noticed certain things come in and I’ve never gotten any of them. I don’t know when they’ve been put out, but it hasn’t been when my big eyes and big mouth have been around. [laughter] So we accept that. That’s just the way things are.

Many of us grew up in families, the oldest child always knows, where you have to divide everything exactly, otherwise your younger siblings complain that you did it unfairly and you got more of the good stuff and they got more of the bad stuff. But we have to grow beyond that mind, don’t we? We have to get over that. And it’s just, whatever people offer, whatever is there, we eat. Sometimes they put too much salt in, we can dilute it with water. Sometimes they don’t put enough salt to our taste, tough luck. Take it as your practice. Or you go over there and (add) lots of soy sauce, lots of Bragg’s, lots of salt, lot’s of this…. And then you get high blood pressure. Congratulations. [laughter] So I think we try and eat in a healthy way. And really look at our mind.

[In response to audience] Also the monastic precepts allow for breakfast and lunch. When you do the eight Mahayana precepts, when we do them for one day, then everybody just eats one meal a day. But for example when people come for retreat, if they do the eight Mahayana precepts for a period of days, then I tell them it’s fine to eat breakfast and lunch, because it’s allowed within that precept.

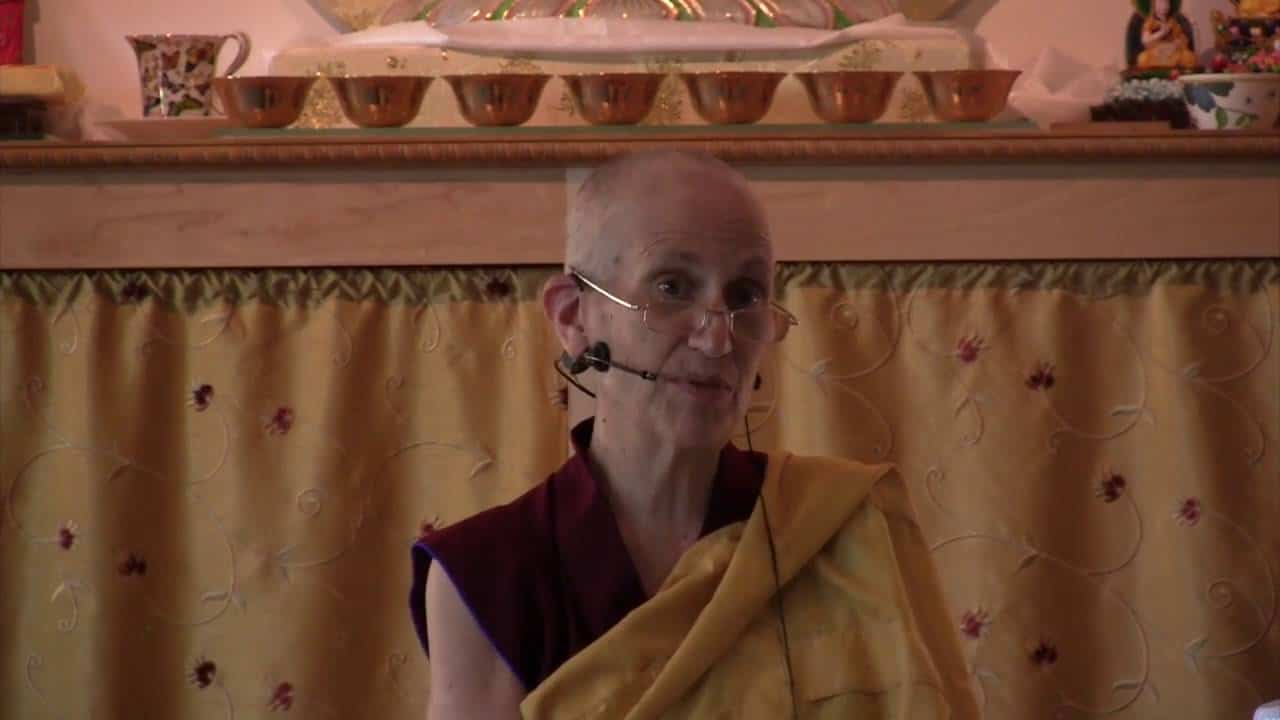

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.