Bad friends

Part of a series of teachings on a set of verses from the text Wisdom of the Kadam Masters.

- Continuing with the factors that cause the afflictions to arise

- The definition of a “bad friend”

- Being careful about who we associate with

- Redefining friendship and family relationships

- How people practice according to their abilities: not all Buddhists are buddhas

Wisdom of the Kadam Masters: Bad friends (download)

We’re still on the second line,

The best discipline is taming your mindstream.

Yesterday we talked about taming the mindstream, meaning to deflate the afflictions and eventually eliminate them. Then we got into the topic of what makes the afflictions arise, what are the conditions that make them come up.

Yesterday we talked about the seed of the afflictions, or the predisposition of the afflictions. We talked about coming in contact with the object that incites our afflictions. That’s one of the reasons with monastic precepts, why the precepts help us to stay away from the objects that our afflictions go towards, some of the standard things. They regulate our behavior with the objects that most people get attached to, so it’s very helpful with not making the afflictions arise. And then we also talked about inappropriate attention, the wrong kind of conceptualization that sees things in distorted ways, exaggerating their good qualities, exaggerating their bad qualities, thinking they’re permanent, and so on, they have intrinsic pleasure in them, whatever.

There are three more of the six conditions that make afflictions arise.

The fourth one is detrimental influence. This chiefly refers to “bad friends.” It doesn’t necessarily have to be friends, but it’s whoever influences you in a negative way. It could even be a family member. In fact, very often the people who we consider “bad friends” are people who, in a worldly way, we’re very friendly with and who want to be our friends in a worldly idea of friendship.

In a Buddhist context, a bad friend is somebody who is going to incite your afflictions: they want to take you drinking and gambling, and out to the movies and the shows, and this and that; they want to take you shopping, drinking and drugging; they want to take you everywhere, out, have a good time. They’re the people who say, “Ah, save your money, don’t make a donation to the charity or the temple, keep it for yourself, we’ll go on a cruise in the Caribbean, we’ll go backpacking in the Himalayas….” These are the people who, in a worldly way, they wish the best for us. They want us to have a good time. But because they don’t have the Dharma perspective on life their idea of happiness is not the same as the Dharma idea of happiness. They’re not thinking about our future lives. They’re not thinking about what kind of karma are they going to involve us in creating. They’re just looking at, “You’re my friend and I want you to be happy right now.” But that criteria for Dharma friendship doesn’t work, because that criteria can really take us away from the Dharma.

A bad friend would be somebody who criticizes the Three Jewels, and tells you to go get a life and don’t waste your time going to retreat, don’t waste your time being a monastic, go out and have a boyfriend and have a career, and make a life for yourself. You know, all this kind of stuff. We have to be careful about who we associate with because those people can either trigger our virtuous seeds or trigger our nonvirtuous seeds to arise. We have to be quite careful about this.

One of the things that people often comment on at the beginning of their practice is, they start to practice, they start to change, then it’s like, their friendships aren’t the same as they were before. What their friends want to do isn’t necessarily what they want to do. And what they want to do, their friends don’t really want to do. But then these new Dharma practitioners say, “What’s happening? Is Dharma taking me away from my friends? That’s no good.” Or, “What’s wrong with me that I don’t want to do what I used to do?” All these kinds of things come up. And then this thing of, “Oh, but they’re my friends forever.” (Actually they aren’t, but we think they’re my friends forever….) And it would be terrible for me to abandon them….” All sorts of confusion comes in the head.

This is very typical and normal. I don’t think it has to be a problem, because even without the Dharma—let’s say you never met the Dharma—are all your friendships going to stay the same forever? Are the people that you’re friends with now necessarily going to be your friends in five years or ten years? If you moved across the country to get another job are you going to stay in touch with these people and be as close to them as you are now? Just even in a normal life our friendships ebb, and grow, and change, and morph and everything else. It’s nothing to get all upset about. When they start to change because of the Dharma it’s just a very natural kind of process.

It doesn’t mean that we have to cut off our old friends: “Oh, you’re bad for me, get out of here!” Come on, they’re kind sentient beings. We’re kind to them. We’re compassionate. We’re polite. But as our values change then the way we relate to these people is obviously going to change. And there’s nothing wrong with that, it’s a very natural thing. Like I said, even if you hadn’t met the Dharma your relationships are going to change. It’s nothing to blame the Dharma on. It’s nothing to feel guilty about. It’s just impermanence at work in our world.

Similarly with family members, I know I had to find a new way to relate to my family because they certainly weren’t in agreement with what I was doing, and if I let what they were saying influence me I would not be here today. Sometimes with family you have to find ways to relate to them so that either they know to subdue their criticism, or you just learn how to completely let it go and ignore it.

As you get into the Dharma then the thing is to really choose our friends wisely. For me I guess it was a very natural thing, because for me meeting the Dharma meant I went halfway around the world to India, so of course…. There was no internet then so you couldn’t stay in touch with your old friends. So very naturally things started to change. But even with internet and so on, you can’t spend all day (well, maybe you can) just doing Facebook and texting your old friends. But then your life shrinks into something that’s [the size of a smartphone] with no real live human beings in it.

As we get into the Dharma then it’s very natural that sometimes our friends change. Some of our old friends may remain the same. In fact, some of you who are here right now are here because the people who were your old friends, who are now sitting beside you in robes, were your old friends that you used to go drinking and drugging and all that kind of stuff with. So you all kind of managed to change together, and all abandon Charlatananda together, and wound up here. For some people it happens like that. Other people it’s an individual process.

What our parents used to tell us about birds of a feather flock together is really true. We want to put ourselves together with people who are going to really encourage our virtuous attributes, and people who will comment when we’re sloughing off, or when we’re getting lazy, when we’re getting negligent, when we’re stuck in our anger, or about to do something nonvirtuous, these people will kind of tap us on the shoulder and say, “Hey, as a Dharma friend can I remind you of this, that, or the other thing?” And in that way we really help each other.

I think we’ll get on to the last two on Monday. Friends took up a lot. Anybody have comments or questions?

[In response to audience] The next one that I’ll talk about on Monday is verbal stimuli. That’s where a lot of those things come into play, our relationship with the media. But it kind of goes between verbal stimuli and detrimental influences. That’s in there for sure.

[In response to audience] We’ve heard this from a few people, that they’ve gotten into the Dharma, they now have Dharma friends, but their Dharma friends want to go out to the pub and they want to go smoke a joint and they want to go to the movies and they want to go to the casinos, or whatever, and then you get really confused because hey, these are my Dharma friends, they’re the ones I meditate with, we have the same teacher, we do all these things together, how come they’re acting like that? Are they really my friends? Aren’t they my friends? What’s the story? How come they’re acting like this?

People practice the Dharma according to their own ability and in terms of their own comfort level. For those people who still are doing a lot of the things that they used to do before they met the Dharma, they’re practicing at their comfort level, according to their ability. Your comfort level is much broader. Your ability is much broader. So you’re not interested in doing the same kinds of things that they’re still doing. No need to be disillusioned with them. No need to be angry. No need to think that there’s something wrong with you. It’s just that you’re both practicing at different levels of the path.

If those people are doing that, you don’t have to feel obliged to join them. Find the people who are doing, and abstaining from doing, the same things that you want to do and abstain from doing. Within a big Dharma group, go for the people who you have more in common with.

You don’t need to criticize anybody. Just, okay, they’re doing that, that doesn’t interest me, I want to do this. Remember, not everybody who’s a Buddhist is a buddha. People really have different levels of comfort in practicing.

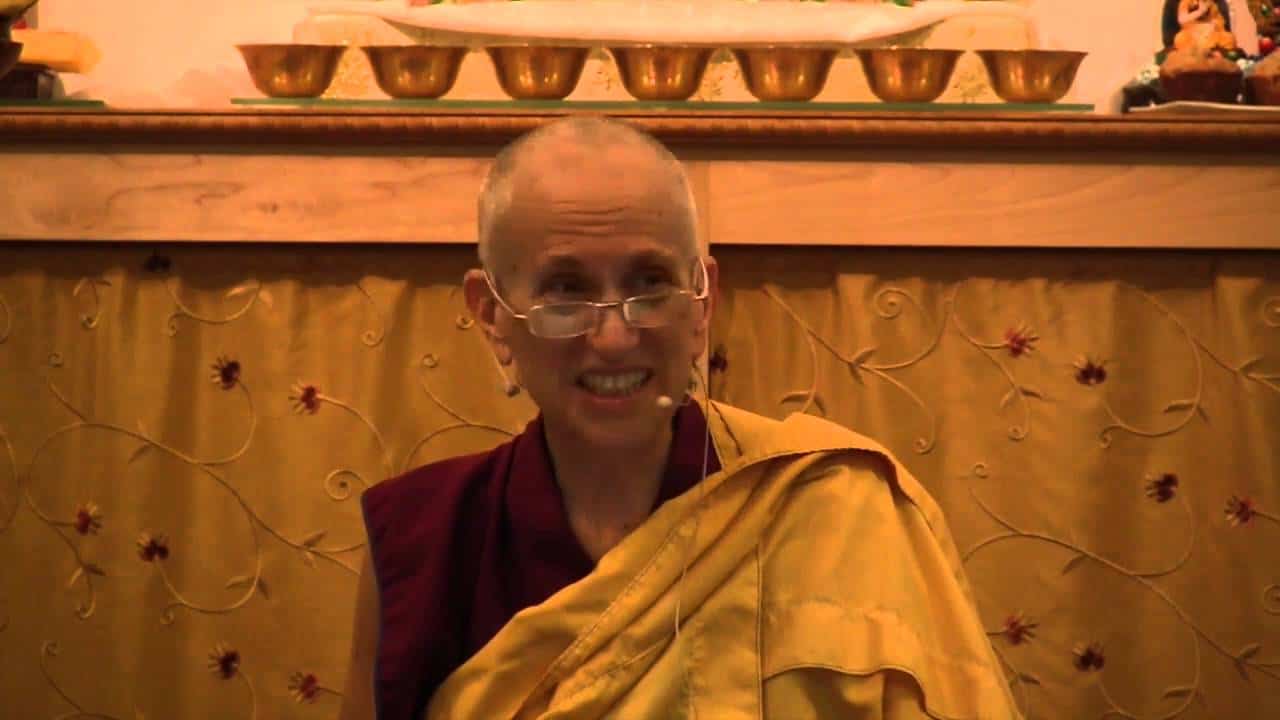

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.