Acknowledging our anger

Part of a series of teachings on a set of verses from the text Wisdom of the Kadam Masters.

- Importance of seeing the disadvantages of the afflictions

- How the afflictions prevent us from developing good qualities

- Examples of how anger creates problems in our lives

Wisdom of the Kadam Masters: Acknowledging our anger (download)

We were starting to talk about the different antidotes to the afflictions. I was saying that before we get into the antidotes we have to spend some time actually seeing the disadvantages of the afflictions, because if we don’t see the disadvantages then we have no impetus to apply the antidotes. Then it just becomes, “Well, I should get rid of this emotion, but actually I really like it.” So it’s very good to spend some time thinking about the disadvantages.

Last time we talked about attachment and I asked everybody to give an specific example of how attachment caused problems in this lifetime. I think that’s quite good to do because it gives you some real live (feeling), you can see it present in your own lifetime. Then, of course, to think of the disadvantages in terms of creating negative karma and causing lower rebirths, and to think that the kind of karma, and by reinforcing those different emotions, then it just creates more and more obscuration on the mind, so it becomes more and more difficult to generate bodhicitta, more and more difficult to realize emptiness.

Especially with the afflictions you can see very clearly how they prevent you from, for example, generating bodhicitta. If you have attachment to sentient beings, how are you going to develop bodhicitta which wants to work for the benefit of all of them equally? Attachment doesn’t let you do that. There’s no way to generate bodhicitta when there’s strong attachment in the mind because bodhicitta has to be based on equanimity and concern for all beings, whereas attachment divides beings into the ones that I like that I want to help and then the ones that (blah), and then the ones I don’t care about.

You can also see how attachment prevents you from generating wisdom. First of all it takes your mind totally on a journey in distraction so you can’t develop any concentration. And when you can’t keep the mind a little bit concentrated then you can’t see the object of negation. In fact, in attachment your object of negation is fully present but you don’t even realize it. It’s good to really think about these.

Similarly with anger, the disadvantages of anger. For all of the afflictions you have the problems in terms of how they cause negative karma which results in unfortunate rebirth, how they block bodhicitta, how they block wisdom. They might block in different ways. Anger, again, how are you going to generate bodhicitta if you have anger? Bodhicitta is based on love and compassion, and anger is the opposite to that. If you’re really harboring a lot of grudges, and anger, and defensiveness, and resentment, bodhicitta is going to be hard.

Meditating on bodhicitta could be part of your antidote to anger as well. I’m not saying you have to get rid of the gross afflictions before you do these other meditations, because the other meditations are part of the antidotes. But you can see that it’s hard to generate the antidote when the affliction is really powerful.

Anger, too, I think in our lives creates a lot of problems. Like we did last time, let’s go around and have everybody give a specific example. You don’t need to mention the name of the person you got mad at, but a specific example. Or maybe it’s just resentment in general. But something specific and how it causes problems in your life. Not how it’s overestimating things, like that, but just how it helps make problems and suffering.

How anger creates problems

[In response to audience] With anger talking harshly to a loved one in the hope that that would change his behavior. It did the opposite, it resulted in them getting more angry at you which caused you a lot of suffering. And then also the pain of feeling guilty afterwards for what you said.

[In response to audience] Anger and then, again, harsh speech, and then it pushed the other person away and created a real breach in the relationship that’s been very difficult to mend. That’s a problem. Especially if it’s someone that you see frequently, than every time you walk in the same room everybody’s (on edge), and everybody’s afraid to talk to each other.

[In response to audience] It’s kind of similar, out of anger speaking harshly, and then somebody who wasn’t an enemy became an enemy, and then again it creates suspicion in your mind, both ways people are suspicious of each other, which means there’s a lot of awkwardness in the relationship, and a feeling of awkwardness and discomfort. “What’s this person thinking about me?” We’re not relaxed and they’re not relaxed. And it effects, especially if there are other people around, if you’re in a community of friends or group of friends.

[In response to audience] Yours was getting angry and shutting down and completely backing away from the friend who did something that you felt was morally objectionable, and it took you 10 years to begin to see the other person’s side of it.

[In response to audience] You lost a friend, then it split the group of friends that you were both members of into different factions.

[In response to audience] Your boss would give you lots of stuff to do, you got resentful, like her, you backed away, shut down, put on the headphones, focused on your work, shut everybody out, so you were suffering and gave yourself no way to resolve your own internal suffering, and how it affected the office you worked in, because when somebody’s like that it ripples through. Don’t we all know, you feel it.

[In response to audience] Having a lot of expectations of people and how they should be, getting angry when they don’t do that, and taking out on them–sometimes withdrawing, sometimes just dumping on them–and then, again, it creates problems in the relationship, and you don’t feel so good about it afterwards.

[In response to audience] A situation where you and somebody else didn’t see eye to eye, you had different opinions, you got angry at them, and then the painful thing for you was you kept on going around and around in your mind about why you’re right, and why she’s wrong, and spending days on this, ruminating, and when we ruminate it’s really unpleasant, isn’t it? Then also, like you said, the relationship became quite strained. Not at all relaxed.

Ruminating is very [blech] isn’t it? And yet we can spend a whole lot of time doing it.

[In response to audience] A situation where you got blamed for following the rules, and then because of that started speaking badly about somebody behind their back, and got all the people you worked with on your side. Oh, that was already in place, but you activated them. You reinforced the thing so that the whole school you were working in became very unpleasant to be in because there was so much anger.

[In response to audience] You get angry at rule-breakers, because if people break the rules then there’s the fear of chaos. And that’s quite scary. We’ve got to make people adhere to the rules at all costs.

And [audience] described it in terms of withdrawing, but that’s not always what you do. (If I can make a comment.) [laughter] It’s one of the things you do, withdraw. Sometimes you let the person know that they’re breaking the rule and that they need to shape up. What happens, the problem it creates, is a lot of discomfort in your own heart because the rumination, the fear that lies behind the anger, and then of course dealing with the people afterwards. You find it very difficult to go to the person and talk about it because the anger and the fear just block you. So it interferes with relationships. And again, as you said, you can cut the energy in the room with a knife.

[In response to audience] You would be working on a project with somebody, come back, they did something you didn’t like, or did it the wrong way, you would go ahead and just undo it and make it the way you wanted it, but find yourself ruminating and blaming, and feeling very uncomfortable about it. And of course the other people (may I venture?) maybe they came back and saw that and got really, really angry? [laughter] Sometimes.

[In response to audience] Oh yes, so you grumble. That makes people pretty unpleasant doesn’t it? Grumbling.

[In response to audience] Somebody who is supposed to be assisting you and then doing what you don’t consider assisting, what they may or may not consider assisting, who knows? Then the mind ruminating a lot on possible motivations for what they’re doing. That’s another part of the rumination, isn’t it? It isn’t just rehearsing what he said, she said. We have to do our psychoanalysis of the other person and attribute some sort of really mentally imbalanced motivation to them doing whatever they did. Even though they may not even be aware that we’re angry because they don’t see a problem with what they did. But for you one of the problems is that you don’t sleep well at night because you’re angry, and you’re ruminating, you wake up in the middle of the night and you can’t fall asleep.

[In response to audience] You can see some similarities in what people said. Also different varieties on different things. It’s really good to really sit and think of the problems our own anger causes us, without feeling guilty, without hating ourselves because we get angry, but seeing the anger as the enemy, differentiating ourselves and the anger. We’re not saying “I am anger, therefore I hate myself because I get angry and I’m an awful person because i get angry.” Not like that. But seeing the anger as a function of the self-centered mind and knowing it’s not who we are, it’s not part of the nature of our minds. So pointing a finger at it and seeing that emotion is the one that torments me, so I want to oppose that emotion. But it doesn’t turn into self-hatred.

It’s good. When we see the disadvantages of our anger then it really motivates us to change. And again, if we’re angry it’s hard to meditate on love and compassion, but of course that’s the antidote we need to meditate on, isn’t it?

[In response to audience] Why are we all more sensitive about revealing situations of anger, whereas last time talking about our attachments we were more open and we could laugh? Because anger is so clearly a negative emotion that we don’t like admitting that we have it. And I think that’s why jealousy is even harder to admit than anger, because it’s even more disgusting. That’s my idea.

But I think it’s really helpful for us to admit it and to talk about it because otherwise, if we’re always trying to hide it, other people know. Who are we hiding what from? Because we’re usually the object of their anger, so we know they get angry. But for us it requires some amount of clarity, and humility, and transparency to just say, “Well, you know these people know anyway, so i don’t need to put up a show about being Miss Goody Two Shoes here.”

[In response to audience] With anger it’s so clear that we hurt other people that again we feel shame, we feel regret, we often get angry at ourselves. That could be one of the reasons why it’s so uncomfortable to talk about it. We have a hard time accepting that we’ve behaved that way and caused that kind of pain.

Which I think, in a way…. The fact that we have remorse about it…. And this kind of shame you’re talking about, that’s the good kind of shame, not the bad kind of shame, but the feeling like, “Gee, I can do better than this. And I need to do better than this.” That in itself I think is a virtuous mental factor. If we got angry and we didn’t feel any kind of regret or any kind of (discomfort) then we’d probably be a psychopath. Wouldn’t we?

[In response to audience] Our attachments we think are cute. Like, “Oh, how silly I was.” But the anger, you’re saying, also most of us when we were younger got really criticized by parents, teachers, whoever it was, for our anger. That adds a layer of saying to ourselves, “You’re a bad person for getting angry,” and that makes it difficult to speak about the anger in front of other people, because then they’re all going to know what a bad person we are.

Amazing how we tie ourselves in knots, isn’t it? This is all conceptuality.

[In response to audience] We haven’t accepted our anger, so we don’t have a sense of peace in ourselves. When we can accept it it doesn’t mean we continue getting angry, it means we stop shaming ourselves. We stop beating up ourselves. That creates some sense of space in our minds where we can actually look at the anger and then do something about it. Whereas when we’re all tied up with, “You shouldn’t get angry, and you’re a bad person because you get angry, and everybody hates you because you’re angry, and they all know that you’re a bad person….” then there’s no way for us to even deal with our anger because there’s all this other static in the mind.

[In response to audience] It was hard for you to see your capacity for cruelty. Even when other people tried to help you get over the anger at that friend, you refused.

That’s why some people go through their whole lives holding these kinds of grudges. Their entire lives. And it’s very painful.

I think we should learn also to laugh at our anger. Don’t you think? [laughter] Because sometimes, I mean, if we can look at the stories that lie behind our anger, the stories are really rather stupid. Aren’t they? So if we could look at those stories and say, “They’re so stupid!” In 7th grade Peter Armeda said this, therefore all the way through the rest of junior high, high school, and into college we’re in the same classes and I refused to speak to him.” That’s really dumb, isn’t it? And I can tell you the story, and a lot of people would tell you, “You were right to be angry at him. You should be angry. He was prejudice. He was biased. He was anti-semitic. You should be angry.” And then…?

But I don’t want to hold onto that. I don’t want to hold onto that. No way.

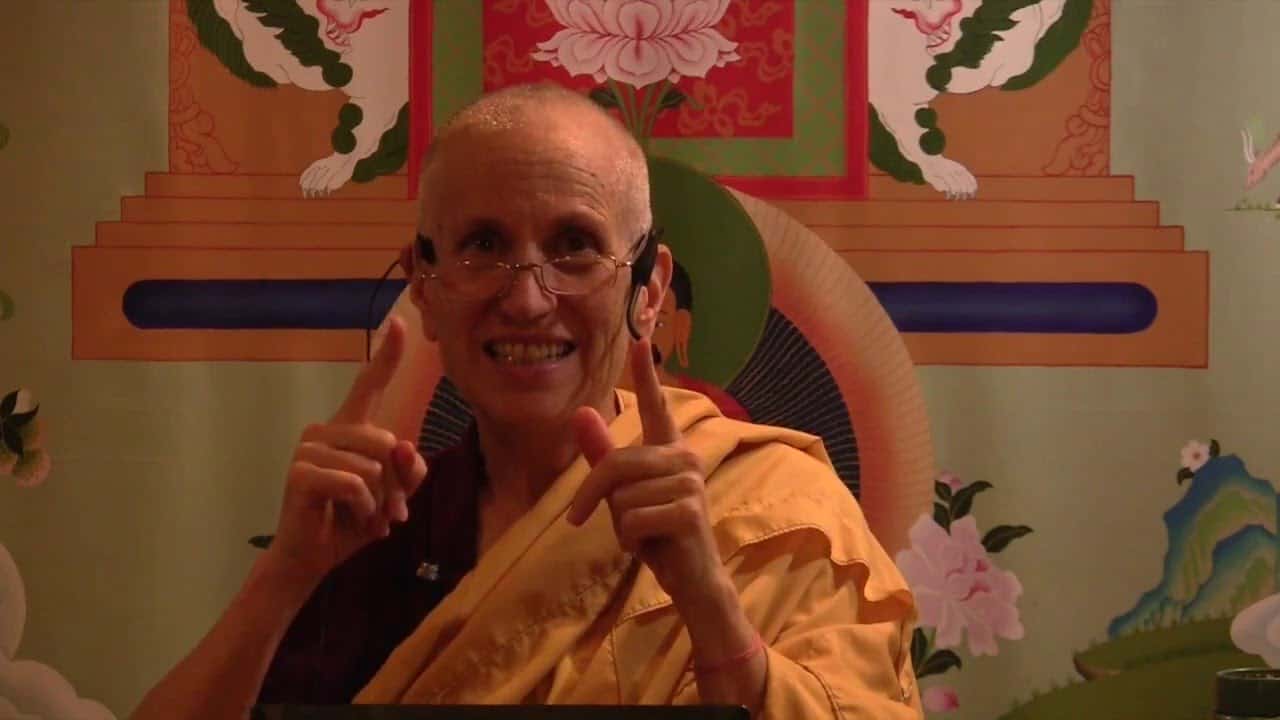

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.