Verse 94: Those with right livelihood

Part of a series of talks on Gems of Wisdom, a poem by the Seventh Dalai Lama.

- External livelihood and internal motivation

- Five wrong livelihoods for monks and nuns

- The danger of looking at others in terms of what they can give you

- Working for the benefit of all beings, regardless of what they can do for us

- Maintaining the mind of bodhicitta

- Being sincere human beings

Gems of Wisdom: Verse 94 (download)

Verse 94 says, “Who amongst those who have achieved human rebirth have found the most meaningful livelihood?”

Audience: Monastics [laughter]

Venerable Thubten Chodron: I think this crowd is biased. [laughter]

He said, “Those who dedicate their days and nights to goodness and happiness for all.”

Who amongst those who have achieved human rebirth have found the most meaningful livelihood?

Those who dedicate their days and nights to goodness and happiness for all.

It’s showing that the external mode of gaining your livelihood needs to be supported by the correct motivation of caring for other sentient beings, and having that long-term vision of bodhicitta. So it isn’t just the external work you do or whatever, but we have to have that bodhicitta motivation.

For monastics, when they talk about the way we earn our livelihood it has to be done without the five wrong livelihoods of

- hinting (to get what we want),

- flattering people (to get what we want),

- putting people in positions where they can’t say no,

- giving a small present to get a big present (being hypocritical),

- pretending to be an elevated being (you know, an arya, “Isn’t that person so lucky to have you around that they can accumulate so much merit by making offerings to you….”) Inflating your own status.

All these kinds of things. Or saying, “Oh, somebody else gave better gifts….” I mean it all kind of comes down to coercion and hypocrisy and bribery and so forth. But instead of those kinds of attitudes, it involves—what were his exact words? “Dedicating your day and night to goodness and happiness for all.”

It’s very easy when your life depends on the generosity and kindness of others—or even if you’re not a monastic and you’re a lay person working for a charity of some sort, where you’re depending on people’s generosity—that you start looking at people in terms of how much they can possibly give you. And that’s disgusting. It’s disgusting if it happens in a monastic’s mind, and I think it’s equally disgusting if it happens in the minds of laypeople in a charity. Our relationship to human beings should not be based on how they can benefit us, either materially or through whom they can introduce us to—important people, blah blah blah. But we should really treat everybody in a similar way, working for the happiness and goodness of all, no matter whether they’re rich or poor, well connected or not.

That’s really something that I think really is quite corrupting in the world, when we start to see other people in terms of what they can do for us. Because then they just become objects, plain and simple. We don’t care about them, we just care who else they know that they can introduce us to, or how famous we can be by associating with somebody who’s very famous, or how much they can up our status, or give us donations, or whatever. And so we want to really be quite careful about having that attitude and making sure that we’re constantly cultivating love and compassion and bodhicitta for others.

Similarly for a lay person who works a regular 9-5 job (or 8-8 job nowadays), still having the motivation of bodhicitta and really caring about others, that’s what is going to make your career worthwhile. Not assembling, lining up your duckies so you can climb the corporate ladder, not playing one person against the other person in the office place so that you can make yourself look good. Not doing all these kinds of things that people often do (in order) to either get more money or more prestige in their job. It might mean talking bad about somebody else behind their back, criticizing somebody to the boss or to the manager, pretending that you did all the work on the project but basically you just showed up the last day, to claim some glory…. So all these kinds of things that happen in one’s career that again if we’re just looking out for ourselves it becomes very, very corrupting. Whereas if we generate bodhicitta and have a good motivation then we can benefit our colleagues, we can benefit the customers or the clients, we can benefit the family, we can benefit ourselves through the power of our positive motivation. So that’s really, really important, whether you’re a lay person working at a job or a monastic depending on donations.

What it boils down to is we have to be sincere human beings. That’s the bottom line. Because if we’re not sincere, who are we fooling? Because the workings of karma is infallible, so if we have a really corrupt motivation that’s going to come out in terms of the result we experience from our actions, even if our actions look very nice to other people in the moment. So it’s something to pay a lot of attention to. And if we have a good motivation in whatever work we do then our work becomes really wonderful and very beneficial for all sentient beings. And it helps us in our future lives and on our spiritual path as well.

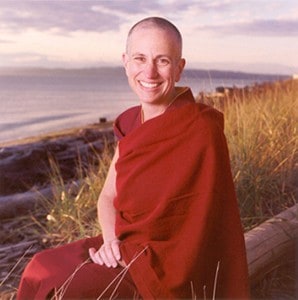

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.