Verse 95: The wisest amongst learned beings

Part of a series of talks on Gems of Wisdom, a poem by the Seventh Dalai Lama.

- What to practice, what to abandon

- Dharma practice is about more than ethical discipline and karma

- Doing what we’re capable of while being aware of the ideal

- Using our own wisdom in learning, thinking about, and meditating on the teachings

Gems of Wisdom: Verse 95 (download)

Who are most wise amongst the learned beings of the world?

Those who use their hands to take up and put down what is appropriate.

He’s not talking about physically taking up and putting down with your hands. What he’s talking about is what to practice and what to abandon on the path. What practices you take up and you integrate into your life and you work on to develop, and activities you put down because they’re leading you away from where you want to go.

It’s kind of like the ability to discriminate well between what is constructive (what is virtuous) and what is destructive (or nonvirtuous). Because if we can’t discriminate virtue from nonvirtue then making even the simplest decision we become paralyzed. We can’t move because we’re just so afraid of doing something wrong.

So we have to learn, through studying about karma, and that helps. But practicing the path isn’t just about karma and ethical discipline, it’s also knowing the other practices to take up and practices to abandon. Or activities to do, activities to stop doing. We learn these when we study the other teachings. The lamrim teachings. Even Ornament to Clear Realization, we learn the bodhisattva path and their practices, what the deeds of the bodhisattvas are. So we learn what we need to start to practice (even if we can’t practice it perfectly), and we learn what to start abandoning (even if we can’t abandon them perfectly).

I remember some years ago—I think like in 1993—Alex Berzin and I were talking and he was commenting about how the teachings are always presented in the most ideal way, about how a bodhisattva acts. And he was saying, “But we’re not totally people who don’t know anything about the Dharma, but we’re not bodhisattvas (high level bodhisattvas) either, so how do we practice, somewhere in the middle. Which of course is a very broad range of things. And he asked His Holiness in the conference, and His Holiness said, “You just practice and do the things as best as you can.” And it made me realize that whenever we hear teachings—because we’re presented with the best, optimum way of doing something, the way a buddha would do something—then in our minds we set that standard that that’s what I’ve got to be able to do. But we’re not capable of doing it, and then we feel like failures and beat ourselves up. Whereas His Holiness was just saying, look, you’re getting the whole complete instructions of how to do things the best way, and what else is the Buddha going to teach you? Half of the instructions you need for how to do it? Or is he going to teach you the not best way? Of course, he’s going to give you the whole, complete best way instructions so that you have all of that in your mind, and then of course the only alternative you have is to do what you’re capable of doing. There’s no other alternative. Because you can’t do more than you’re doing. I guess the other alternative would be giving up totally, but that’s kind of stupid and useless. So His Holiness said you just do the best you can. Which is so practical and makes so much sense, doesn’t it?

So at the same time we’re learning these glorious bodhisattva activities that are immeasurable and limitless and inconceivable, instead of comparing ourselves to those bodhisattvas (and coming out as a dimwit) it’s better to, you know, that’s our model, that’s where we’re going and so we just do the best that we’re capable of doing. And by doing that then we will slowly be capable of doing more and doing better. That’s the only way to progress.

Knowing these teachings—what do you practice, what do you abandon—is very very important because if we don’t get the whole full, complete, best-case scenario, vision of that then we won’t even try and practice that. We won’t see that as something to practice. And we’ll get very confused about what to practice and what to abandon.

So much of the path is described in these ways—what to practice, what to abandon. In Precious Garland [the Thursday night teachings] last week when we started to talk about the Buddha’s qualities we talked about his qualities of abandonment and his qualities of realization. That’s the outcome of what to practice (you have the Buddha’s realizations) and what to abandon (you have the Buddha’s abandonments). So it’s always presented in this way, the things we have to let go of, overcome, and the the things that we want to cultivate and realize. So we do that on the path, as that’s the path to get somewhere, and then the final result is the abandonment and realization of a fully awakened one.

(We) use our own wisdom—first to learn these, the wisdom of hearing, thinking about them so we have the right idea, having that wisdom, and then the wisdom of practicing and meditating and integrating these in our lives. And then we become one of those “who are most wise amongst the learned beings of the world.”

Being the most wise isn’t about rocket science. You can meet people who have incredible degrees and they’re geniuses according to worldly intelligence, but in terms of the Dharma, they’re super dull. They’re the dull beyond the dull disciples, because they don’t understand anything about the Dharma because the mind is totally shut closed. So being wise, being intelligent in the Dharma is very different from being wise and intelligent in worldly ways.

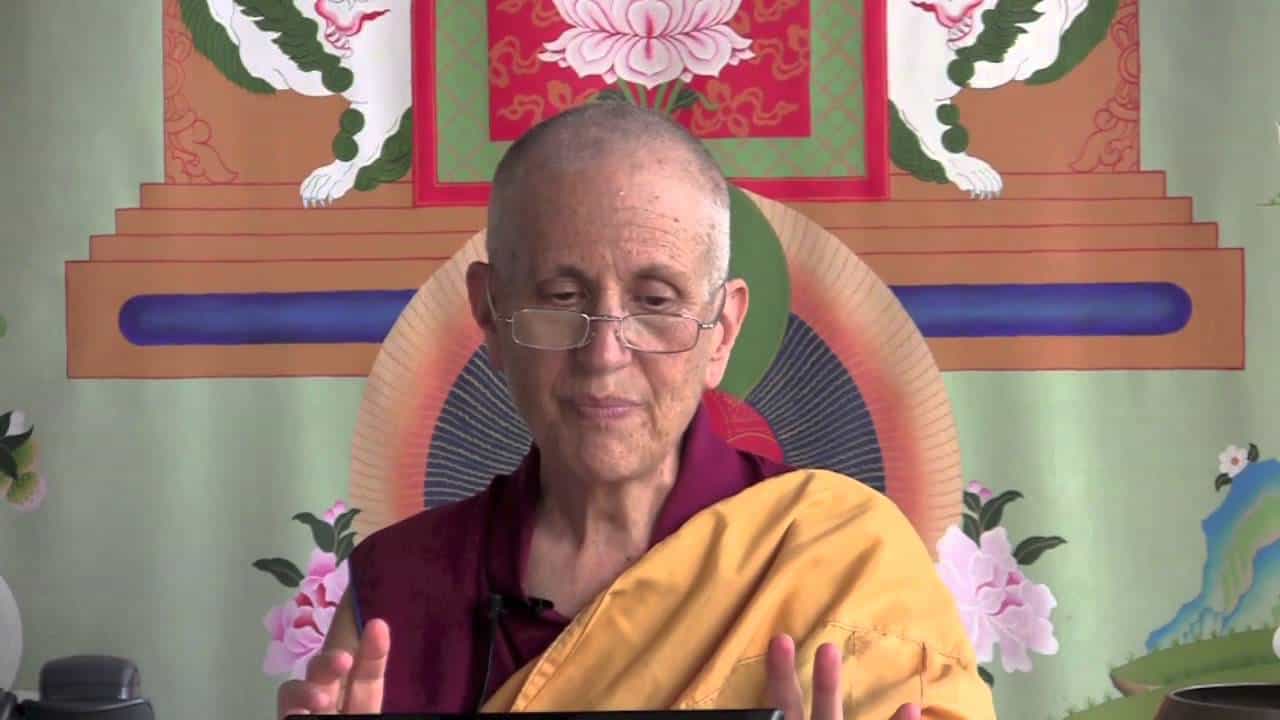

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.