Bodhisattva ethical restraints 11-18

The text turns to training the mind on the stages of the path of advanced level practitioners. Part of a series of teachings on the Gomchen Lamrim by Gomchen Ngawang Drakpa. Visit Gomchen Lamrim Study Guide for a full list of contemplation points for the series.

- Teaching on the last eight of the root bodhisattva precepts

- There is no contradiction between the vinaya and the bodhisattva precepts

- Lying about spiritual attainments

- Four binding factors that must be present for a complete transgression

Gomchen Lamrim 85: The Bodhisattva Ethical Restraints 11-18 (download)

Motivation

Let’s start with our motivation. Today was a big day at the Abbey and a big day for the creation of a lot of merit, a lot of virtue. During an ordination ceremony you have to remain incredibly focused, you can’t space out for a moment. It keeps your mind in a virtuous space by that force and afterwards you feel quite good. So, I think, I hope, everybody feels that way this evening and can really see for your own experience how subduing the mind and keeping the mind in a constructive state, in a virtuous state, is the cause of happiness now and of course in the future as well. Especially when we have the bodhicitta motivation, when we’re doing things with that motivation and a far-reaching intention, all the cares of this life just evaporate because they aren’t important anymore and the mind takes great delight in doing what is really important in the long term, for the benefit of all beings. Cultivating that bodhicitta motivation again, let’s listen to the teachings.

Rejoicing in monastic ordination

Does everybody feel happy this evening? Nice, huh? All of you who cooked and prepared, thank you very much. There’s something, isn’t there? Sometimes we say, “Oh rituals, ceremonies,” (I used to think like this) “So dry, so boring, everybody’s just saying all this stuff, repetition, repetition.” But you can see (maybe if we did this every day, it would be different) in doing an ordination ceremony it’s like everybody’s really present and you really feel the goodness involved in everybody there changing their mind and putting their mind in the Dharma. It’s not just the person who gets ordained, but it’s the Sangha, the preceptor, the viharia, the witness, everybody is changing their mind and putting their mind in a good direction. I don’t know if you noticed, I’m probably more familiar with this ceremony than many of the others of you, that although this is a ceremony for taking the monastic precepts which are on the level of the fundamental vehicle, they aren’t a bodhisattva practice, in the ceremony how often things about bodhicitta and compassion come in. There are little phrases here and there. So, you can see, when we were speaking with Venerable Wuyin in ‘96 in the Life of a Western Buddhist Nun program she commented that one of the reasons the Chinese chose the Dharmaguptaka system was because it fits so well with the bodhisattva vehicle. Even though it is a fundamental vehicle ordination, it fits very well with the bodhisattva practice. You could really see that in the ceremony.

The bodhisattva precepts

Now we’re going to continue going on with the bodhisattva precepts. We finished number nine or number ten, so we’re starting then eleven. It’s very interesting with each of these two, to go through them as you go back and contemplate them and say, “Why is this particular action antithetical to the bodhisattva motivation or to bodhisattva actions?” You could see, especially number nine, “Holding wrong views,” which is a very serious one. How could you even be practicing the Dharma if you’re holding wrong views, let alone following the bodhisattva path? And number ten, “Destroying towns, villages, cities” and so on, similarly, that certainly wouldn’t be something a bodhisattva would do.

Number eleven,

Teaching emptiness to those whose minds are unprepared.

Someone whose mind is unprepared means somebody who hasn’t heard the basic teachings, precious human life, death, refuge, karma, the four truths of the aryas, something about bodhicitta. In other words, this person does not have a grounding in the Buddha’s teachings on conventionalities and conventional truth. Especially if they don’t have a strong grounding in karma and its effects, some people if they learn emptiness and they misunderstand it think that emptiness means nothing exists. Then they think karma and its effects don’t exist and therefore there’s no reason to keep ethical conduct. With that kind of wrong view, they throw ethical conduct to the wind and wind up creating the cause for an unfortunate rebirth. So that’s the reason why. It isn’t [because] emptiness is a secret teaching or it’s a high teaching or this or that. It’s just because it’s easy for somebody who doesn’t have sufficient grounding to misunderstand it.

For example, in the emptiness meditation where you start asking “How does the I exist, is it one and the same as the aggregates or is it totally separate from the aggregates?” Somebody could look and say “Well it’s not one with the aggregates, it’s not totally separate from the aggregates, those are the only two choices, so the I doesn’t exist at all.” The thing is, those are the only two choices if the I existed inherently. But if the I exists conventionally, there is another choice which is that the I exists dependent on the aggregates. It’s not totally one and identical with them, it’s not totally separate, it’s dependent. But somebody who doesn’t understand this then just says, “Well, it’s not one, it’s not different, there’s no I. And if there’s no I, then there’s no one who creates karma, so there’s no karma so I can do whatever I want.” And that’s a very, very dangerous view because it gives the person permission to follow whatever idea pops in their mind without stopping to think “is this something virtuous or non-virtuous?” Because karma doesn’t exist so everything’s empty, everything’s non-existent, that gives them permission. So it’s very very dangerous.

Nagarjuna spoke about this in chapter one of Precious Garland, how it’s easy for people to fall into this kind of extreme. As somebody who is teaching, whenever you’re teaching you have to be very aware about who your audience is. If it’s people who are brand new, you really have to give them the teachings on the conventional truth, meaning renunciation, bodhicitta, these kinds of things; not go into a teaching on emptiness. Sometimes you can hint around about emptiness or bring a little bit in here or there, but you don’t want to go full force into it because it could be dangerous for the other person. And even people who have heard a lot of teachings can sometimes misunderstand too. Also, they tell the story about the one who grabs his dhonka and says, “Am I still here?” That happens when you get an inferential realization of emptiness. Even at that point, emptiness is so vastly different from how we look at things now, that even for that person, they’re going, “Does anything exist and yank on their…”

Any questions?

Audience: A lot of people, when they first hear about emptiness doze off or something, I wonder if that’s a self-protection mechanism.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Oh, it might be.

Audience: Just not being prepared.

VTC: Right, right, people fall asleep in teachings, even not teachings on emptiness, even something that they could understand if they were awake.

Number twelve

Causing those who have entered the Mahayana to turn away from working for the full awakening of Buddhahood and encouraging them to work merely for their own liberation from suffering.”

Here’s somebody who has entered the bodhisattva path in terms of having faith in it, following it, doing the bodhisattva practices and then we come along and say “why are you doing that? Why are you practicing the Mahayana? It’s too . . .it’s unrealistic. You want to enlighten all sentient beings? You can’t do that. There’s so many Buddhas already, they can’t do it. So why are you exerting all this effort? And it takes so long to do the Mahayana path. Better, it’s much shorter, less merit, less time to become an arhat following the sravaka path. So, do that.” Somebody could think about it and go “Well yes, there’s already all these Buddhas, so I don’t need to do it and it’s true, it takes three countless great eons, that’s really a long time, and let’s get myself out of samsara first because, after all, if I’m not out of samsara I can’t benefit anybody anyway.” So, they give up bodhicitta and give up the bodhisattva path and practice the path to arhatship.

It’s not that the path to arhatship is bad, arhats are much more highly realized than we are. So don’t disparage arhats, that’s not a wise thing to do. But it’s just if somebody has entered the Mahayana path and has that inclination and has started to follow it, turning them away from it is actually harmful to all sentient beings. It means it’s going to take that person much longer to become a Buddha because they will go through the whole arhat path, spend a while -a few eons- in meditation on emptiness and then have to go back and start the bodhisattva path at the path of accumulation. So, it takes longer for that person to get to enlightenment which is not so good for all the sentient beings who have karma with that person who that person could benefit if they were a buddha. That’s why we don’t do that. It’s discouraging the people from it.

It could be in different ways; you could say the goal’s too high, “Oh Buddhahood, that’s too high, too hard, omniscience,” you trash the goal; or disparage the path, “[The] bodhisattva path is so difficult, you have to give your body, you have to give up all your own pleasure, you have to work for sentient beings even in the hell realms, and they’re so ungrateful, so don’t waste your time on those beings.” Saying the path is too hard or it could be saying that the person who is the basis practicing, “Oh, you know, you just don’t have what it takes to become a bodhisattva, you’re not smart enough, you don’t have enough compassion.” So, disparaging either the basis- the person, the path or the result and in that way talking somebody out of following the bodhisattva path. We don’t want to do that.

When I was in Thailand, a few of the western monks, there was one western monk especially and he questioned “What are you doing?” And there were other monks who came to us and said, “tell us more about your practice.” Of course I told them. I was talking bodhicitta surreptitiously every opportunity I had (laughs).

We’ll go to thirteen

Causing others to abandon completely their precepts of self-liberation and embrace the Mahayana.

Twelve was causing somebody to give up the Mahayana and practice the fundamental vehicle. Here you’re talking to somebody who is practicing the vinaya, those are called the precepts of self-liberation, because the basic foundation motivation for taking them is a wish for your own personal liberation. So, somebody who has those precepts and discouraging them from keeping let’s say their ordination, their monastic precepts, and instead embracing the Mahayana instead. This could be the same thing. Kind of “What’s the use of being a monastic?”

“Come on!” I’ve heard this. “Its twenty-five hundred years ago they were doing that. And we’re in the modern age now. And you guys are celibate? That’s nutty! You’re suppressing your sexuality. Forget about you’re not enjoying life, it’s true, you’re not enjoying life, and no, I can’t do this, no, I can’t do that but you’re actively suppressing your sexuality, that’s totally unhealthy. It’s not natural, you need to go have a relationship, and relationships are really good on the path. When you are in a relationship you have to give up your own self-centeredness. Because if you’re going to make your marriage go… and children! Children are experts at making you get rid of your self-centeredness. As a parent, because you have to get up in the middle of the night and feed them. And you have to go to work, and you have to put up with them when they’re yelling and screaming. And so, let me tell you, family life will get you to enlightenment much quicker. This monastic thing is old-fashioned.”

Audience: You’re copping out.

VTC: Oh, yes, this is the big thing, it’s because you can’t have a relationship. You’ve tried, and you’ve had failed relationships. You’ve been divorced, you’ve been in love, and they’ve rejected you, so you’re a failure at relationships and that’s why you want to become ordained. This is a big thing in Asia, what they say, their image of monastics especially nuns. The nuns are the old maids who couldn’t find some rich, handsome guy to marry.

So, they say “Better you give up your monastic life and practice the Mahayana. Anyway, Mahayana’s faster, the bodhisattva precepts are a higher level of ordination than the pratimokṣa precepts, so why keep the pratimokṣa when you can keep the bodhisattva, and bodhicitta you accumulate more merit having that. So just give back your robes, have a nice wardrobe, let your hair grow out. When you go to the disco you can meet so many people and talk Dharma there to them. And in the pub, all the people in the pub are suffering so much. You can go to the pub and talk about Dharma to them and in that way, you could spread Dharma so well. Whereas if you’re one of these stodgy monastics, you certainly can’t go into the pub and do that. So, get with it if you want to benefit sentient beings.” Have any of you ever had somebody say something like that to you? I’ve heard it.

Audience: I don’t speak for myself, but this person said “Oh, you’re so attractive, and how can you do that? No, don’t do that!”

VTC: Yes. In Dharamsala when I went into the fabric shop down in lower Dharamsala to get my robes, to get the cloth for my robes, this one man looked at me and said, “what a pity, you’re so pretty you should really get married, not become a nun.” “I’m not pretty and I don’t want to get married.” Kind of like “Oh, there’s an attractive sex object, what a misfortune that nobody gets to . . .” (laughs).

Audience: Remember when Venerable Chan Guan when people said, “You are only a monastic because your relationships have failed,” he would say, “And what’s wrong with that?” He said “Many people have had failed relationships, and they go out and kill people or get drunk and do all kinds of crazy things. It’s very good that you failed in a relationship, and you became a nun or a monk, excellent.”

VTC: Yes, he is right, really; because many people go out and get drunk and drive when they’re drunk and do all sorts of nutty things when their relationships break up. Very true.

Audience: It seems (it is a rationalization obviously) when you become a monastic, talking from someone who is just looking at the team, it seems that you have way more relationships than I do.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: I was wondering if this could also be disparaging the five lay vows?

VTC: It could be too. If you have a lay person who has taken all five precepts and their friends want to take them out to drink or somebody’s flirting with and wants to have sex with them and they say “No, I have a precept,” then the friends “Yooow (moaning) you don’t take intoxicants, you’re one of those prudish Buddhists.” And then disparage everything. That’s not very good.

Audience: But even somebody that’s encouraging them to take bodhisattva vows might be…

VTC: Yes, you’re disparaging one encouraging “You can take the bodhisattva vows because look there’s one bodhisattva vow that says that if it’s for the benefit of all sentient beings you don’t need to keep the pratimokṣa vows, so if you want to convert sentient beings in the pub you got to go and be among them and you’re doing it with the bodhicitta motivation.” That precept is so often misunderstood and used as a big rationalization.

So, we can see here from twelve and thirteen that both keeping the monastic precepts and following the bodhisattva path are important and that both of them can be done together in a complementary fashion. That’s the conclusion from these two precepts. You can do both in a complementary fashion so that there’s no need for us to have to doubt either our pratimokṣa precepts or doubt our bodhisattva practice. This could also be “What’s the use of vinaya, Mahayana is better.” If you keep the pratimokṣa, one translation for it is the ethical restraints for individual liberation so somebody could say “Oh, you keep those, those are just for your own individual liberation. That’s very selfish. You should practice Mahayana instead. Give that up and practice Mahayana instead because then you are working for the benefit of others.” That comes from somebody not understanding that the pratimokṣa is the foundation of the bodhisattva practice and that you can also keep the pratimokṣa with a bodhicitta motivation.

Fourteen

Holding and causing others to hold the view that the fundamental vehicle does not abandon attachment and other afflictions.

Number six, “Abandoning the holy Dharma by saying that the texts that teach the three vehicles are not the Buddha’s word” would be for example, disparaging one of the fundamental vehicle scriptures and saying that they aren’t the Buddha’s word. Fourteen is talking about the practice, not the scriptures. Fourteen is saying that the fundamental vehicle practice doesn’t work. Six is talking about the text and fourteen the fundamental vehicle practice, saying that it doesn’t abandon attachment and other afflictions.

Now, why would somebody think that? Possibly, the only reason I can think, is because I think it was around the time of King Ashoka, so probably third century B.C., there was a convocation or a conference of the monastics and there was this question brought up about “Can you be an arhat and still have afflictions?” or “Can you be an arhat and then fall back to samsara?” So maybe somebody has that kind of view. Or maybe it’s just somebody who doesn’t like the idea of having to give up attachment. So, you say, “Well, that vehicle doesn’t really abandon attachment anyway and I actually don’t want to abandon my attachment, and so, just forget the whole thing.” That’s the only reason I can think of why somebody would think like that. All these things you can see come from people misunderstanding the teachings, either not having heard teachings and not having the correct understanding or having heard them but misunderstood. Or having somebody who, like Nagarjuna says, one of the cows that’s leading the others and leads you down the wrong path.

Number fifteen

Falsely saying that you have realized profound emptiness and that if others meditate as you have, they will realize emptiness and become as great and as highly realized as you.

If you say this kind of thing and it’s motivated by jealousy and attachment it could very well be the first root downfall, “Praising yourself and belittling others,” especially the praising oneself part. “I’ve realized emptiness, I see the ultimate nature.” If you’re doing it out of jealousy and attachment in order to have more disciples, in order to get more offerings, then it’s the first one, the first root downfall. It’s also a form of lying because this is talking if you haven’t realized emptiness, so it could be lying.

This precept specifies emptiness here, but it could be other realizations that you claim to have. “The animals talk to me like they talked to St. Francis;” or “I have psychic powers, and I can see into the future and do this and that;” or “I can pass through walls or walk on water” or “I have samadhi, I have serenity, I have actualized the fourth jhana.” This is something where you know you haven’t and yet you claim you have. It’s kind of like the root precept that the monastics have of lying about realizations.

This one, you can really see when you get put in a position of being the leader of a group or a teacher, if you have a lot of people around you who just think you are fantastic, worship you and they think you’re so highly realized and so wonderful, it’s so easy. I’m especially thinking of monastics when they’re not living in a community. One monastic living in a Dharma center with lay people and the lay people just worship you and think you’re wonderful. You have no other monastics around who kind of know who you really are and who you do confession with. But you have all these people just adoring you and then you start to think, “Well, I am pretty good. These people think that I’m really good and they think my explanations on emptiness are really wonderful, they think that I must have realized it, maybe I do have some understanding of emptiness, it’s pretty good, maybe I do have an inferential realization.” Or whatever other kind of thing. “All these other people are saying I’m so kind, that I’m a bodhisattva.” Because you have all these disciples, “you’re so kind, you have so much compassion.”

Audience: You and I have been practicing for a really long time and both have known people who have gone down that road, and so would you be kind enough to just say a few words about what really helps you not go down that road. Because you’ve been the Dharma teacher, the sole monastic for many many years before you established this place and certainly if you wanted to put yourself on a high throne you could do it around here too. So, . . .

VTC: On the top of the table. My throne supported by four cats! Who needs snow lions when you can have cats?

I just look at my own mind – there’s afflictions in my mind – so what am I going to do, say I don’t have afflictions? That would be ridiculous. I think if you just look at your mind at all and are at all even a little bit honest with yourself, then you don’t go around proclaiming that kind of stuff. But yes, we’ve seen people do that. Then the disciples of those people are amazing. I remember being at one teaching sitting near the disciples of one person who was like that and like, “Oh, our teacher, he’s at least [at] path of seeing; we’re sure, he’s just wonderful.” I didn’t say anything, I don’t know somebody’s level of realization, but I wasn’t impressed.

Audience: I have to say that in response to your question and witnessing you over the years, I’ve always thought that the thing that probably must have served you really well in this regard is the value of transparency. I’ve seen you admit to things, when you can and it’s appropriate, that a lot of people wouldn’t. So that is not just honest to yourself, but you’ve been honest with others and made that a priority for us as a community. And even before we were a community it was a value. I always thought that was quite important.

VTC: Hmmm, could be.

So why is there a precept against doing this? Because you deceive people. You’re deceiving people. And deceiving people regarding the Dharma is the worst kind of deception. Because if you make claims to have realized something and then you fall flat on your face, all these people lose faith in you, they could also lose faith in the Dharma. And if you do things that make people lose faith in the Dharma, that adversely affects them for many many many many many many lifetimes. So, it’s something that you really don’t want to do.

Also, if you get self-inflated like this or if you start thinking maybe you have these realizations, or even you know you don’t, [but] you pretend like you do because the disciples want you to. Because disciples can put a lot of pressure on a teacher to act in a certain way and the disciples want you to look holy, so you look holy. And then you put on this thing that you have some high realizations, then the disciples love it. They’re really impressed because they want to be the student of some far-out somebody. Then afterwards, we’ve seen with various scandals, somebody falls flat on their face, then a lot of people get very hurt spiritually because of it. That’s really the worst way of hurting somebody. Somebody could think, “Oh, breaking up a love relationship is the worst way to hurt somebody,” no, that is not going to influence you for many many lifetimes the way harming somebody spiritually would. And then it harms yourself as well. If you start thinking you’re hot toast, then “Oh, I don’t need to practice anymore because I have realizations, so I don’t need to practice.”

Audience: So, you spend your life deceiving yourself and others, gaining a lot of fame and fortune and notoriety, [and] at the time of death, and then where from there? Does that really cast you out of ever really having the Dharma in your life in a sincere way or is it even more serious than that?

VTC: I think you’d spend quite a while in the hell realms. Maybe you created some virtuous karma too, you probably did somewhere along the path, and you’ve been seeing holy objects and there’s something. That could cause a rebirth later on, but it would be quite bad for one’s own future rebirth, actually.

It’s really true when you look sometimes, the pressure from the disciples is tremendous on some teachers.

Audience: It reminds me of The Wizard of Oz, and the citizens just want to perpetuate that.

VTC: Yes, the citizens of Oz wanted the wizard, didn’t they? I forgot, how did he get to Oz?

Audience: In a balloon.

VTC: Oh, yes, and then they thought he was wonderful, and he set up this whole thing and pretended to be a wizard because they wanted that.

Number sixteen,

Taking gifts from others who are encouraged to give you things originally intended as offerings to the Three Jewels, not giving things to the Three Jewels that others have given you to give to them or accepting property stolen from the Three Jewels.

This is directly or indirectly acquiring the property of the Three Jewels.

Taking gifts from others who were encouraged to give you things originally intended as offerings to the Three Jewels.

Somebody is intending to make an offering to the temple, you know that they’re going to offer it to the temple and you say, “I really want to do retreat, I haven’t done retreat in so long and I’m not sure where I’m going to go because I would really like to build a retreat house and I don’t have the money to do that,” and then the person thinks, “instead of giving the money to the temple, I’ll give it to this person.” In the person’s mind they had already dedicated the money for the temple, but due to our smooth talking they changed their mind and gave the money to us instead. They say when you’ve decided to give something to someone it really isn’t yours after that point. So sometimes you have to say to yourself “I think I’m going to give this to someone” if you think that you might change your mind somewhere in there. But if the donor is sure that they’re going to give it, then they change their mind, it’s negative karma for them and it’s negative karma for you for making them change their mind and giving it to you. There’s one of the bhikkshuni and bhikkshu precepts that are similar to that.

Not giving things to the Three Jewels that others have given you to give to them.

So, you’re going to Bodhgaya. And your friends in the States give you money and say, “Please will you make offerings at the Bodhgaya stupa, if you go to Nalanda, make offerings there, make offerings at Sarnath for me, just buy some candles or some incense or put it in the dana box there but make offerings for me at the holy place.” They give you money, you go on your pilgrimage, and you have this money and then you see, maybe a beggar, and you think, “oh, I should give the money to the beggar.” Or maybe you see another fellow traveler who has just run out of money, and you think, “Oh, I should give the money to that person.” Or maybe you want a really really nice meal after eating dal bhat, so you’re tired of eating dal bhat, you want a really nice meal, so you use the money that somebody gave you that was meant for the Three Jewels.

Or maybe you’re going to the Dharma center or something and somebody gives you a box of cookies or some food and says, “Please make offerings at the Dharma center for this, put it on the altar, or you’re going to a temple, to a monastery, give it to the Sangha.” On your way there you have a flat tire and you’re waiting on the highway. You’re hungry and you think “well, I’ll eat that and then I’ll buy something else that I give to the temple.” No, because the person had dedicated that specific box for it. I think in terms of money, you don’t have to give the specific bills because it’s the value of the money that’s important and certainly if you’re going from one country to the other, you’ll be changing money. But if it’s a material thing you should give that exact thing that somebody gave you to give to the Three Jewels and not give it to someone else. And if you know that something was meant for the Three Jewels and somebody’s giving it to you, don’t accept it and say, “please use that to make offerings.”

Audience: But I do feel uneasy if somebody gives me money to offer and then if I lump it together with my own funds when I change money, it does strange things in my mind. I would designate “This is given to me for offering by somebody else” and when I change money that becomes that piece.

VTC: Right, you keep it separate from your own money.

Audience: It’s very difficult for me to lump it and exchange the money together.

VTC: You might change the money together, but then you sit down and figure out what proportion of it is your money and what proportion was given to the Three Jewels and then you separate that out and keep it in a different envelope.

Audience: Yes, sometimes to the extent that I can’t quite put them together to exchange in a lump.

VTC: That’s fine if you exchange them separately too.

Audience: The mind doesn’t like it, it’s messy for me.

VTC: Whatever is easier for you, do that. The important thing is to make sure that donations go where they were meant. And the same thing even if somebody gives you a donation for Save the Children, then you should give that donation to Save the Children, you don’t give it to some other charity or keep it for yourself or something like that. If Save the Children went out of business, and you couldn’t give it to them, you would give it to a similar one but tell the person or write them beforehand and say, “Can I do that?” It’s always good whenever you’re uncertain regarding a benefactor, to contact the benefactor and ask. There’s nothing wrong with that. We’ve done it sometimes here. It shows integrity on your part.

Another example they give is fining monastics. Stealing from monastics actually comes under number five so if a minister or somebody in the government, put fines on four or more fully-ordained people, it would be number five and here is if it’s one, two or three monastics, because you need the four or more to become a Sangha.

I didn’t do the last phrase,

Accepting property stolen from the Three Jewels.

If you suspect that something has been stolen from the Three Jewels, either don’t accept it or accept it and then try and return it. Like when the communists went through Tibet and China and ransacked temples, and you found incredible holy objects on the market being sold in Hong Kong that had been stolen actually from the temples in Tibet and China. Those kinds of things you would not buy, or if you bought them, you would take them back to the monastery where they came from and offer them back to the monastery there. Or somebody gives you something that was stolen from the Three Jewels, again, not keeping it but trying to give it back in some way or another. Then anything else about that one?

Audience: What about those stuff that are now in a lot of the museums that had been taken during the colonial times, how does that work? And if you are working there and you have the bodhisattva vows?

VTC: If you were the one acquiring these things that were taken during colonial times, if you were a Buddhist and you had the bodhisattva ethical restraints, you would be breaking it in this way. So much of this, like when they found different things in Dunhuang, the Brits took a lot of stuff. Are they stealing that from the Three Jewels? Because there weren’t really temples there, it was all ruins, and they took things from ruins. They may be stealing from the government, and I know in some cases the governments in India and China have asked these museums to repatriate the things that were taken during colonial times. I think they should, it actually belongs to that country.

On the other hand, if you were in Afghanistan and you knew the Taliban was going to destroy these things, if you took them out with a motivation to protect them and to protect Taliban people from creating so much negative karma, that I think would be positive. There were some people when the communists overran Tibet that really tried to take statues and texts, especially texts, out. But many times, they were probably their own texts, or they were monks from that monastery and on behalf of that monastery they would take the texts out to preserve them. They did a great service because otherwise these things would have gone up in fire. It’s quite amazing when you go to those places, both in Tibet and China, where you just see broken parts of statues and parts of texts lying around and it’s really an awful awful feeling to see that, just all this rubble. Dispersed in the rubble are parts of holy objects and parts of holy texts. You can only imagine the karma that those people create.

Seventeen,

This has a few parts too.

Causing those engaged in serenity meditation to give it up by giving their belongings to those who are merely reciting texts or making bad disciplinary rules that cause the spiritual community not to be in harmony.

If you commit one or the other, it’s a transgression.

Causing those engaged in serenity meditation

Somebody is meditating, trying to gain serenity. They’re working hard at that and staying in a retreat situation so that they don’t have so much distraction. Your friend is reciting texts, and you would really like your friend to get the donations and things, so you take things that were meant for or already possessed by the people doing retreat and you give them to people who are reciting texts or something like that.

That is not so good to do because the people who are doing retreat and trying to actualize serenity are doing some really useful meditation that will really further them along the path. People who are reciting texts, that’s very good, that’s virtuous, but the people who are really trying to put things into practice by meditation are doing something more intense. Also, those people in retreat have a harder time getting requisites. The people who are reciting texts in town have an easier time getting requisites. So [not good] taking things from the people doing retreat and then giving them to other people who aren’t in retreat.

The other kind, part B could be… either you’re somebody in the monastic community or maybe you’re a government employee making laws. The government makes laws that cause a monastic community to be in disharmony. Or maybe somebody in the community itself who has some power makes some kind of law or rule within the monastery that causes a lot of friction. It could be for example during the cultural revolution, if somebody were a Buddhist and had these precepts, going into a monastery and saying the monastics can’t study and meditate anymore; they have to go to communist propaganda courses and learn propaganda; that kind of thing.

Another example: at Larung Gar, in this monastery in the high Sichuan Province, the government is being quite hard on them, and I saw one picture. What is true is that there is a definite fire hazard there because the people are living very close to each other in wooden buildings. There’s been ravaging fires before and so there is reason in one way to tear down some of the buildings and do things differently. But some of those monastics are having to leave and go back to the temples where they started out from. I saw one picture of a bunch of nuns. They were in work clothes lined up and they were reciting communist propaganda things, that’s what the government made them do after they left the monastery. That’s causing the community to be disharmonious and it’s really interfering with people’s spiritual practice, so that’s creating a lot of negative karma.

Or making some disciplinary rule like if somebody here said “Ok, nobody can study and meditate, everybody has to go and get a job in town because we need more money so everybody has to go and get a job in town.” That’s not going to be so good. We’re talking about rules like that, not rules like “from now on we’re not going to have junk food in the kitchen.” That might cause more disharmony than anything else (laughter). No more junk food. But that’s something that could be protecting the monastics and extending their life span. Maybe we need an executive order like that. Except the kind of junk food I like, which is not junk food, it’s actually good for you!

Number eighteen,

Abandoning the Two Bodhicittas,

Here it means aspiring bodhicitta and engaging bodhicitta.

Audience: I have never been able to understand why these two, 17A and B are under the same number, the relationship between the two.

VTC: Because they’re both interfering with people’s Dharma practice. One is by taking their requisites, the other is by making bad rules. People who are really trying to practice and you’re causing them problems.

Regarding these, eighteen [is] to have a full transgression of sixteen you need four binding factors but for two of them, you don’t need these four binding factors. Just having the thought in your mind is sufficient for a root transgression.

Those two are holding wrong views, saying “The Buddha, Dharma, Sangha don’t exist, enlightenment doesn’t exist, it’s impossible, cause and effect don’t exist,” these kinds of things. Once you’re just even thinking that, holding those kinds of wrong views, you don’t need these four binding factors. Same for giving up bodhicitta, either giving up the aspiring or engaging bodhicitta. Just the thought of “I’m done with this bodhisattva stuff” or whatever it is, “I’m sick and tired of sentient beings.”

Audience: The sine qua non of the bodhisattva vows.

VTC: Yes. With both of those, if you have wrong views and if you give up bodhicitta, having the bodhisattva vows doesn’t make any sense for you at all, does it? Before I go into the four, are there any other questions or points?

Audience: Can you do that while still having bodhicitta? It seems like you couldn’t be still holding bodhicitta and still do that.

VTC: You can have bodhicitta, but you could say to somebody else, “Oh, you’re not really bodhisattva material. You’re too selfish or you’re too dumb, or you’re too whatever.” So, discouraging somebody from that but thinking that you’re quite okay for practicing bodhicitta. Let’s say you see somebody who is really, really struggling. They took the bodhisattva precepts, they’re really struggling, they’re unhappy because they’re sitting there blaming themselves, “Oh, I am so selfish, and I can’t keep these precepts very well.” So out of maybe what you think is compassion, you say to them “Oh, it’s okay, just ignore that you took them, Mahayana is not for you, you can give it up.” And you think you’re being very kind helping that person to not be so stressed out. Not so smart.

It’s amazing when you really think about it, the number of things that we can do that are non-virtuous that we do thinking that we are helping somebody. When you see things like that, you know how when they talk about the 10 nonvirtues, that you can do any of them motivated by any of the three poisons, then you begin to understand how you could do these negative actions motivated by ignorance. Because you really think “Oh, what I’m doing is virtuous.” You ignorantly give people very bad advice or do things yourself that you think are virtuous.

Like, “Oh, all these prostitutes, they would benefit so much from learning the Dharma, they would have so much self-respect if they met somebody who really cared for them. So, I’m going to go work in a brothel and just be one of the girls and share the Dharma with them to help them get out of that life.”

We shake our heads but let me tell you I’ve met people who have done amazing things that they think it’s so beneficial and it’s not. You have the men who are going to prostitutes, “I’m doing these girls a favor. They’re poor, I’m giving them some money. So, it’s good. What I’m doing is good. They do something, that’s ok, they are going to sleep around anyway but I am giving them money and I’m kind to them. And so, this is compassionate.” Amazing how people can think. You think we don’t make up excuses and weird motivations? Maybe I should point them out to you sometimes when you say them to me, in the actual moment. So that you can get really mad at me, “what are you saying, nah nah, I don’t do that!”

The Four Binding Factors

The first one,

Not regarding your action as destructive.

So, you don’t even know that you’re transgressing a bodhisattva vow. Or even if you don’t know that it’s a bodhisattva vow, you’re not regarding what you’re doing as destructive, as harmful. Or even [if] you recognize that the action is transgressing a bodhisattva vow, you don’t care. It’s like, “This is just a little transgression, and I really want to do this. My teacher told me to relax and to not be so hard on myself and to have some empathy for myself. So, yeah, this isn’t really a transgression.” That kind of thing.

Then the second,

Not abandoning the thought to do the action again.

So, you’ve done it, and you have no thought to stop doing it in the future.

That goes along with number three,

You’re happy and you’re rejoicing you did it.

“I had such a good meal, my friend gave me some money to make as an offering and anyway the gate was closed when I went to make the offering, so I used the money for a really good meal and I really needed a good meal, and my friend, I know that they’ll be really happy. So, that’s fine what I did, no regret doing it, happy to do it again.”

Then four,

Not having a sense of integrity or consideration for others regarding what you have done.

These two mental factors. Integrity: Abandoning non-virtue out of your own self-respect. “I don’t want to be the kind of person that does that.” Or “I have precepts, my Dharma practice is like this. I can’t do that.” That would be integrity.

Or consideration for others: Thinking of the adverse effect your action would have on somebody else; making them lose faith in the Dharma, making them lose faith in you as a practitioner. I think in the Pali system they talk about this one in a slightly different way, which is “being afraid of being criticized by the wise.” I’m not sure if they give it the same name or if they’re talking about another mental factor. But there’s also that one. That you abandon something out of respect for people who are wiser than you and you don’t want them to criticize you. That would actually fit in there with consideration for others. Because you think “What would happen if my teacher showed up right now? Uhm, hmmm, uhm, uhm. No, I wasn’t drinking, I was just talking with the people here.” You hide your bottle of booze or whatever, you have your arm around somebody, and you quickly take it off them.

To have a complete transgression of the other sixteen, you need all four of those.

There’s sometimes talk of within how much time? How much time do you have before you abandon the thought? Maybe immediately you don’t abandon the thought of doing it again and maybe immediately you feel quite happy about having done it but maybe an hour later your mind has realized what you’ve done or maybe a day later or a month later. Has it been a full transgression if you later come to lack these different factors? I forget what it is. I should really look that up. Somehow, three hours is sticking in my mind, like three-four hours, but I’m not sure. So, not very long meaning…

Audience: I don’t remember, it wasn’t like tomorrow.

VTC: Yes. Oh, no, it’s definitely not tomorrow or next month. No, definitely not that. I can’t remember if it’s immediate or like three-four hours, something like that, or half an hour, whatever.

Of course, if you later come to regret it, that regret is good because that will motivate you to do purification. Don’t think “Oh, I’m too late to regret it and not have it be a full transgression, so I just won’t regret it then.” No, thinking like that is rather dumb.

And then to purify. 35 Buddhas is very good, Vajrasattva is also very good. Then to take the bodhisattva ethical restraints again either from a teacher or you can visualize the Buddha or [if] you have a Buddha statue. Thinking that the Buddha statue is the actual Buddha you retake it, you make the pledge again. Actually, we should be taking the bodhisattva ethical restraints if you have them, three times in the morning, three times in the evening, it’s included in the six-session guru yoga.

Audience: These four factors sound a lot like the factors for any kind of transaction, non-virtuous action.

VTC: No, with other things just doing the action is a complete action.

Audience: I just thought there was something about enjoying having done it, or something.

VTC: Yes, complete karma. It’s just the fourth one, the completion, you’ve done the action, and you feel satisfied with it. If by the time the action is complete you feel regret, that’s not the case. For any negative action you definitely don’t want to have these four with you. It’s not that, let’s say with your pratimokṣa precepts, you need these four to break it. Usually if you look at the state of your mind very often these four are there but they are not included as factors for a complete transgression.

Audience: So, if somebody holds these vows, they go over them three times in the morning and three times in the evening?

VTC: No, you take them. You make the bodhisattva promise, like when we say, “by the merit I create by practicing generosity and the other far-reaching attitudes, may I attain buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings,” that can be considered taking the bodhisattva vow. You do that three times a day, so it could be that. There’s one verse in Shantideva’s text that is included in succession guru yoga that you recite, there’s different ones.

Audience: Which is part of our practice here.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: What about a case, it’s kind of indirect, taking property from the Dharma and the Three Jewels. About several cases actually, that people stole from the offices, and it might have been overnight. They made the decision not to keep any money outside, to bring it to the bank immediately in the afternoons. If you don’t do it you’re kind of risking that the money that is dedicated to the Dharma to the Three Jewels is being taken.

VTC: Yes, places where they get a lot of a lot of offerings you definitely don’t want to leave all that money around because it’s very tempting for people. We’ve had a couple of cases here where people have taken things from the dana basket. And books, library books, yes, so many library books have gotten lost.

Audience: What is the name of our new monastic and what does her name mean? Friends online are rejoicing.

VTC: Stand up here so people can see you.

Audience: Hi. My name is Thubten Nyima and it means sunshine.

VTC: Nyima means sunshine and Thubten?

Audience: Thubten means the able one.

VTC: The able one’s teachings, the Buddha’s teachings.

Contemplation points

Venerable Chodron continued giving commentary on the bodhisattva ethical code, which are the guidelines you follow when you “take the bodhisattva precepts.” Consider them one by one, in light of the commentary given. For each, consider the following:

- In what situations have you seen yourself act this way in the past or under what conditions might it be easy to act this way in the future (it might help to consider how you’ve seen this negativity in the world)?

- Which of the ten non-virtues is the precept keeping you from committing?

- What are the antidotes that can be applied when you are tempted to act contrary to the precept?

- Why is this precept so important to the bodhisattva path? How does breaking it harm yourself and others? How does keeping it benefit yourself and others?

- Resolve to be mindful of the precept in your daily life.

Precepts covered this week:

Root Precept #11: Teaching emptiness to those whose minds are unprepared.

Root Precept #12: Causing those who have entered the Mahayana to turn away from working for the full awakening of Buddhahood and encouraging them to work merely for their own liberation from suffering.

Root Precept #13: Causing others to abandon completely their precepts of self-liberation and to embrace the Mahayana.

Root Precept #14: Holding and causing others to hold the view that the Fundamental Vehicle does not abandon attachment and other delusions.

Root Precept #15: Falsely saying that you have realized profound emptiness and that if others meditate as you have, they will realize emptiness and become as great and as highly realized as you.

Root Precept #16: Taking gifts from others who were encouraged to give you things originally intended as offerings to the Three Jewels. Not giving things to the Three Jewels that others have given you to give to them, or accepting property stolen from the Three Jewels.

Root Precept #17: a) Causing those engaged in serenity meditation to give it up by giving their belongings to those who are merely reciting texts or b) making bad disciplinary rules which cause a spiritual community not to be harmonious.

Root Precept #18: Abandoning the two bodhicittas (aspiring and engaging).

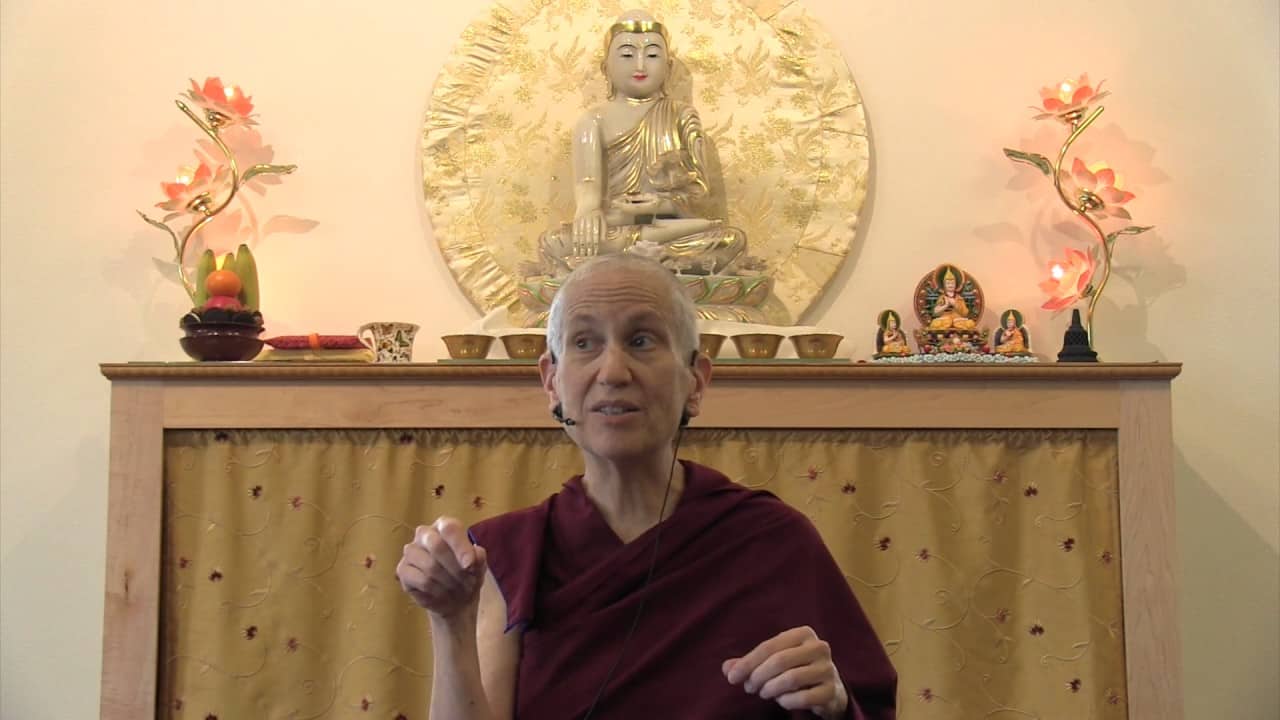

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.