The intention to lie

The Eightfold Noble Path 05

One of a series of talks given for the Bodhisattva’s Breakfast Corner on The Eightfold Noble Path.

Somebody was really thinking very well about what I said in the last talk about lying, because it was an unusual approach to lying, probably one that we haven’t thought of. And it was just me contemplating different things. So, I want to read what this person said and then come into it. It’s Venerable Losang, so a very good reflection here. First of all, he’s saying that usually with lying, as the text says, there’s:

Recognition that what you’re about to say doesn’t accord with the truth and that you intend to distort the truth.

There is that kind of intention and motivation. And Geshe Sopa said very much the same thing in his lamrim commentary. So, he’s not seeing the examples that I gave on Monday as being illustrative of that kind of thing.

If someone says, “You never listen to me,” what they’re saying may not be true, but unless they’re recognizing that and trying to present it as the truth, regardless, it seems to me that it doesn’t meet the criteria for lying. Also, if they think in the next moment, “Well, that’s not true,” it still doesn’t seem to be lying because that is the recognition that what one has said doesn’t accord with the truth, not recognition that what one is saying or about to say doesn’t accord with the truth.

Anger exaggerates, but doesn’t the exaggeration need to be the intention to deceive in order to be lying? Isn’t that what lying is about—intentionally speaking falsely with the motivation to deceive someone else? I would think that most people who say “I hate you” to someone, whether friend or foe, aren’t trying to deceive the other person about how they feel about them. That wouldn’t be the intention.

Intention doesn’t necessarily mean you sit down and plan it out beforehand. Intention happens quickly, like a snap of the fingers. It comes to mind like that. So, yes, there is lying where you sit down and think, “Okay, I want to cheat”—well, you never say, “I want to cheat on my income tax.” You never say that, do you? You say, “I want to declare some things that I spent money on for myself and my family as business deductions so that I won’t have to pay as much tax.” You don’t say, “I want to steal from the government, and I’m going to lie,” do you?

No, we never do that because we’re not people who steal, and we’re not people who lie. We just claim this expenditure was actually for that thing, because we don’t want to pay Uncle Sam so much. Uncle Donny doesn’t pay him, so why should we? Poor Uncle Sam, he’s really having a hard time. And with the tax cuts billionaires are going to get, really Uncle Sam, we have to feel sorry for him. Do you have Uncle Sam in Russia? What’s your version? Uncle Sergei? [laughter] No? [laughter] In Singapore? In Germany? Yeah, it’s the taxman. But Uncle Sam is more than just the taxman, isn’t he? He’s the whole country—the government embodied.

Anyway, you have that intention, so that is like cold-blooded lying in the sense that you’ve sat down, you’ve thought it out, you’ve planned it and everything. But how many things come out of our mouth with an intention that came in just the split-second beforehand? I don’t know if you’ve had this experience—not necessarily about lying but about many things—where, for example, you are starting to say something, and one part of your mind says, “Close your mouth,” but you keep saying it anyways? Yeah? Why? Because the intention is actually there. Then there are other times—again, I don’t know about you—but I say things and then afterwards I think, “Why in the world did I say that?”

Well actually, I wouldn’t have said it if there wasn’t an intention. So, intentions can come quickly, and we may not notice them; they aren’t necessarily so vivid in our mind. So, when we exaggerate—I remember one time someone was talking about their mom telling good stories, and they would say to her, “But Mom, it didn’t happen that way,” and she would reply, “Hush, it’s a better story this way.” So, a lot of times she knew what she was doing, but a lot of times we are embellishing the story as we are telling it. We don’t think beforehand, “How can we make it better?” We’re just ad libbing and making it into a better story as we speak. So, we may not think, “Oh, I’m lying.” We’re just telling the story with a little bit of embellishment to give people more happiness. Isn’t that what we think?

We never think, “Oh, I’m lying.” We think, “I just want them to laugh more and be happy, so I’m embellishing a little bit.” Likewise, when we’re upset with somebody, we want them to really understand how much pain we’re in, how upset we are, so there’s kind of again that little wishful thought, “I’ll just embellish it a little bit” to get it across to that person just how upset and hurt—or whatever it is—I’m feeling.

Again, we don’t think, “I’m going to lie and say I never want to speak to you again.” Because why are you saying, in a loud voice or in a crying voice, “I never want to speak to you again!” You’re saying that, but you do want to speak to them again because you care about that person, and you’re trying to find some way to talk and to get it together. But you’re so ignorant that you do the opposite thing by thinking that is going to help.

Isn’t that what we mean when we say, “I never want to speak to you again”? If the mailman or a stranger did something you didn’t like, you would never shout to them, “I never want to speak to you again!” [laughter] If somebody cuts in front of you in line at the grocery store, do you say, “I never want to speak to you again”? No, you don’t say that to them. We embellish how upset we are in order to get a person’s attention.

But is it the truth what you’re saying? That’s what I’m getting at—is that the truth? And so, somebody brought up a very good point in the discussion last week. When we say it, the other person doesn’t know if what we said is true or not. If it is true then they feel hurt; if it’s not true then they’re going to doubt when you say you love them whether you really mean it. Because maybe you’re embellishing there, too, because you want to get something out of them. Lots of times we’ll do that, won’t we? We want to get something out of somebody, and so we’ll flatter them. “You’re so wonderful. You’re so talented. You did this. You’re that, that, that.”

We say, “Oh, I flattered them.” We don’t say, “I lied.” But was it lying, too, as well as flattery? Did we really believe what we were saying? Did we want to make the other person believe something that wasn’t completely true? So, that’s more the kind of speech I’m getting at, that subtle thing, because really, there are certain things we would never say. We wouldn’t say, “I’m a murderer,” but we will say, “I went hunting and killed an animal,” or “I killed a spider.” Killing—murdering—is not okay. So, we’ll say, “I killed the chicken,” and we’ll have barbeque chicken tonight. We wouldn’t say, “I murdered the chicken.” The government “executes people”; they don’t “murder people.” But, in fact, they do murder people when they execute people, don’t they? It’s government-sanctioned murder.

It’s so interesting. When you use things that belong to your company for your own personal self, you don’t say, “I’m stealing from the company.” You say, “I worked hard and they’re not paying me enough, so actually, I deserve this. This is already mine. I’m just taking what is already mine.” It’s just that other people haven’t agreed that it’s ours, you know? It’s the same with lying. We never like to say, “I lie.”

“I exaggerated it. I embellished it to make them feel happy.” We say anything to cover up that there was a moment there, whether we’re upset or completely calm and doing cold-blooded lying, that we had the intention to lie. In the same way, we don’t like to say, “I stole something,” or “I robbed someone.” We never say that. We don’t like to say, “I spoke harshly.” It’s, “I gave somebody a piece of my mind.” [laughter] “I spoke frankly. I told them what they needed to hear and what they deserved to hear.” Once in a while, we might say, “I chewed someone out,” but it was because they needed it and deserved it, and it was for their benefit.

It’s very interesting, this kind of thing. Do you see? Does it make more sense now what I was talking about in regards to lying?

Questions & Answers

Audience: In meditation this winter, I was looking at the five omnipresent mental factors in which intention was one of them, and I was really trying to figure out how each moment of mind would have an intention. Say I’m doing something, like sawing, and my intention is on that, and I’m moving intentionally, and then a mosquito bites my neck, and my mind is moved to that, but did I intend for my mind to move? It’s very subtle…

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Yeah, the intention comes very quickly, and before we know it.

Audience: Even if I don’t kill it, my intention has gone there, and I’m aware of that.

VTC: Your attention has gone there, but your attention has gone there because there is intention.

Audience: That’s right, and that’s what I found so hard to see, that was one of my examples of that.

VTC: Yeah, very often our intentions are not so obvious to us—even sometimes the gross intentions we don’t even see.

Audience: Venerable, I was thinking about your talk, too, and in that moment when someone blurts out, “I hate you,” we can’t have two opposing mental factors present, so in that moment the mental factor of—

VTC: In that moment there is definitely not attachment. [laughter]

Audience: But there isn’t love there also in that moment? What you were saying the other day, what we really mean is “da-ta-da-ta-da,” but we’re swimming in these afflictions and past karmic tendencies, and, so, even in our virtuous, heartfelt moments, until the path of seeing, when I say to someone that I deeply care about them, is this in fact true? Because I’m afflicted. [laughter] So, it’s kind of perplexing.

VTC: Well, we care about them. It should be noticed that when an ordinary being says, “I care about you,” you need to fill in what’s in parentheses, which may be “I care about you as long as you’re nice to me,” or “I care about you as much as I can,” [laughter] or “I care about you until you drive me nuts.” I’m not saying don’t trust people; I’m not saying don’t trust. Instead, realize that when people say things, they themselves may not be putting in the small print in their own minds.

For example, when people get married, what do they say? “Forever, until death do us part.” And they have discussions about how they’re going to take care of each other when they’re falling apart and they can’t walk. And they say, “Even when you’re seventy eight years old, and you have a catheter in, I’m just going to love you to bits.” And they really mean that at that moment, but if you thought about that, is what that person is saying true? Maybe once in a while they’ll love them when they’re seventy eight, when their catheter’s leaking. Have you ever been around somebody with a leaking catheter? It challenges your love, doesn’t it? [laughter]

So, people may think they mean it, but if you really say, “Do you mean that? Can you say that for sure,” then they would actually have to say, “No, I don’t.” But in the spur of the moment, when attachment is strong, it’s like our wisdom is out the window, isn’t it? And we say things that we really can’t verify.

Audience: Thinking about it a little bit, it seems that there’s also a factor of conditioning, in that sometimes we say or do things that deeply we may not mean, but yet, it’s the expectation of societies, the expectation of the family, the expectation of the workplace, for you to do these things, to say these things, to behave in this way. And even if you have a small hint that, “Hmmm, maybe I don’t really mean that,” you still do it because you have to function in that environment.

VTC: So, are you saying things that we just do automatically or things that we do because we’re conscious that we’re experiencing social pressure?

Audience: Both, I think. It’s really both.

VTC: Yeah, because you may know that there is a lot of social pressure to do something, so you play your role even though your heart is not in it, and it’s really not you. And there is some intention to deceive in that. It might be weaker karma because it’s the force of the social pressure, but still the mind is going along with that. And sometimes the mind going along with that, knowing that you’re not acting sincerely, is actually done to please somebody, and then the reason for pleasing someone could be because you care about them, or it could be just duty or obligation or fear. Of course, there’s the fear that thinks, “If I don’t meet other people’s expectations…” It made me think of the movie The Graduate with Dustin Hoffman, and how when he didn’t do what was expected people were so shocked.

Audience: When I do the Lama Zopa, or sometimes my sadhanas, it seems like I’m not really being truthful. I expect from myself some kind of devotion and some strong refuge and all that, and we’re thinking that if that’s probably lying then I am deceiving the Buddhas because I’m just asserting things.

VTC: Okay, so when we do our practices, our recitations, and our heart’s not in it, they say that is actually idle talk. It’s more idle talk than lying. Let’s say I take refuge in the Buddha, a banana, a hot fudge sundae [laughter], which is really what you’re thinking about. [laughter] That’s a good point.

Audience: In the same line, is fabricated bodhicitta lying?

VTC: No, because you really have that intention to develop bodhicitta. It’s fabricated, but you’re not hating other people at that moment. You’re generating as much bodhicitta as you can, considering that you’re not somebody who has spontaneous bodhicitta. So, it’s the same with the unshakeable resolve that the bodhisattvas make: “By myself alone, I’m going to empty the hell realms.” That’s not lying because you know why you’re saying that. You know that you’re trying to develop your compassion and your joyous effort and things like that.

But Shantideva talks about how when you have taken the bodhisattva ethical restraints and promised certain things, then if you lose your bodhicitta that’s deceiving sentient beings. Because you promised them; it’s like you promised somebody this big meal, and then you back out of it. I think he uses the word “deceived” there if I remember correctly. So, don’t lose your bodhicitta—even the little bits that you have.

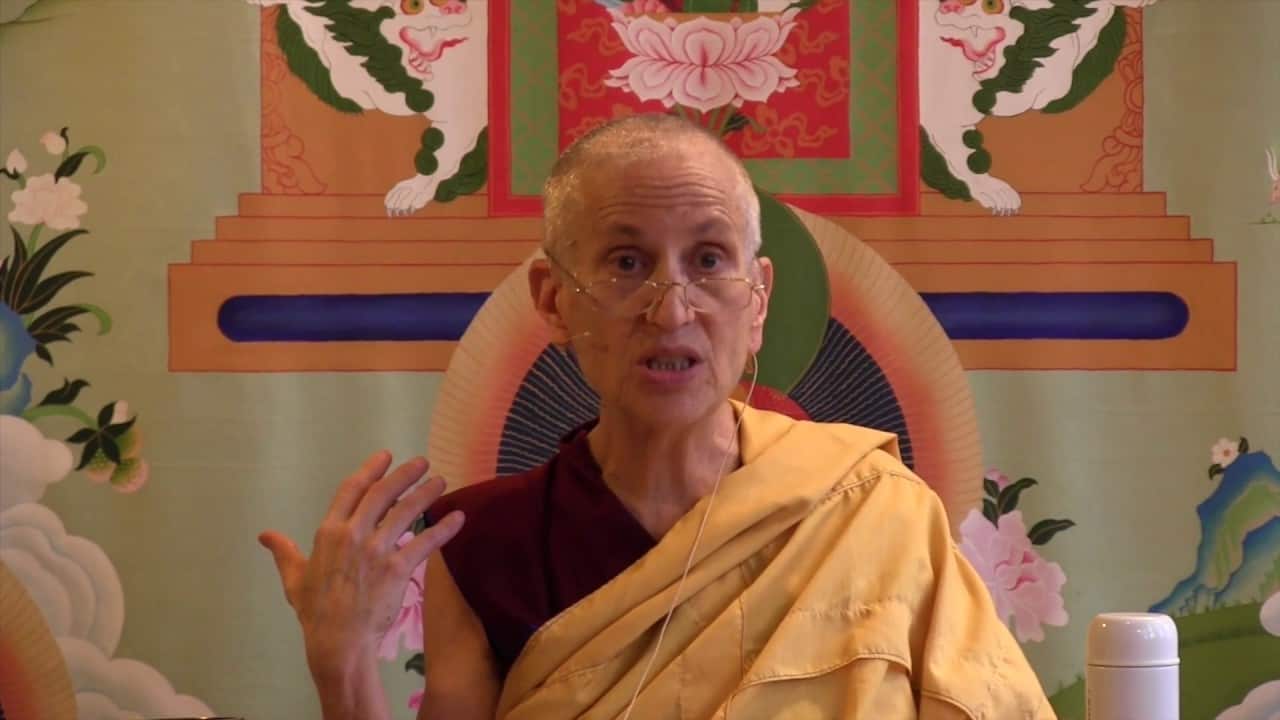

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.