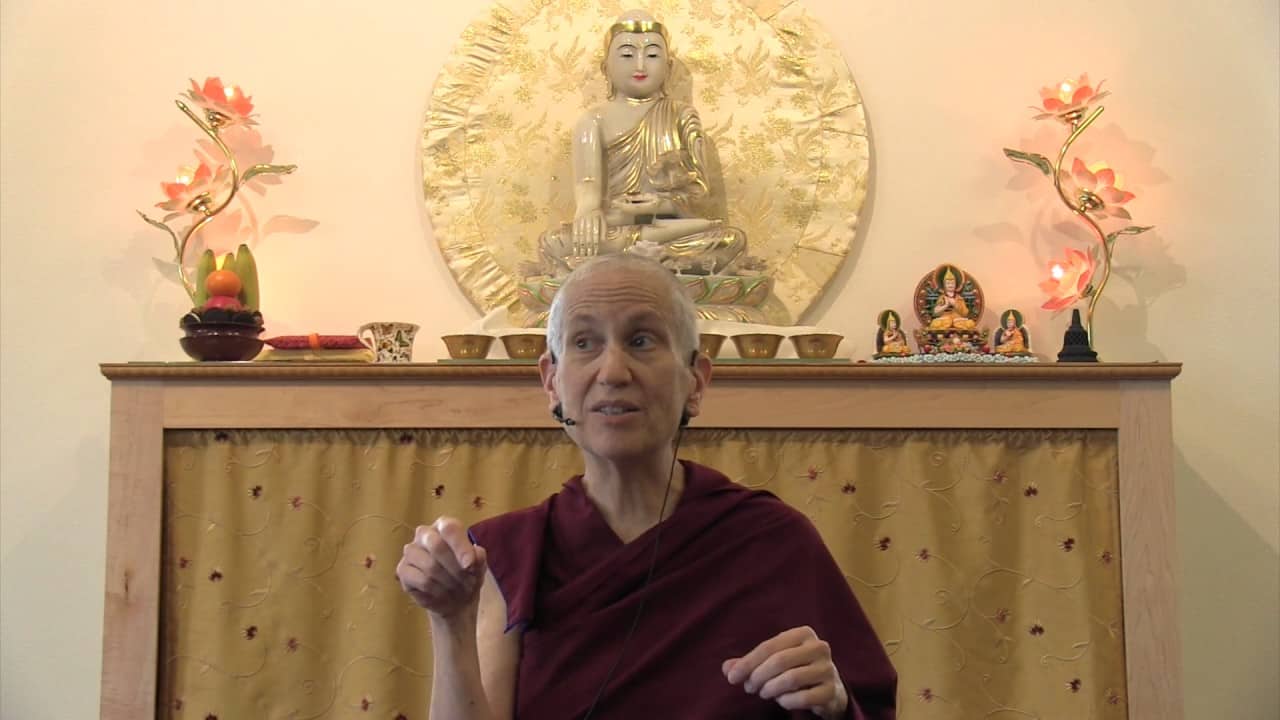

Bodhisattva ethical restraints 5-10

The text turns to training the mind on the stages of the path of advanced level practitioners. Part of a series of teachings on the Gomchen Lamrim by Gomchen Ngawang Drakpa. Visit Gomchen Lamrim Study Guide for a full list of contemplation points for the series.

- Review of first four root bodhisattva precepts

- Teaching on the next six precepts

- Involving secular law enforcement when dealing with monastics

- Discussion regarding advanced directives and assisted suicide

- What exactly is a schism in the sangha?

Gomchen Lamrim 84: The Bodhisattva Ethical Restraints 5-10(download)

Motivation

Right now, we aren’t born in the lower realms. We have human intelligence; we have the opportunity to listen to the Dharma. We’re not in extreme pain or with deformed or inhibited senses. We have a very special opportunity right now and it’s not worth wasting in order to indulge in anger or attachment or jealousy or arrogance or whatever. When we see our opportunity, we know that we are mortal, don’t know when we are going to die and there is no time to waste on having destructive emotions and bad behavior. We have to really make an effort to steer our mind in a good direction. Of course, that best direction is what we were talking about today: right view and right intent, understanding karma, understanding emptiness and having the intention to act without attachment, with benevolence, kindness, forgiveness and with compassion. Let’s try and steer our minds in that direction knowing that sometimes it’s hard but when we look at the alternative, this is the only way to go. So, with an intention to complete the whole path to awakening, however long it takes, however much we have to do, let’s listen to teachings on the bodhisattva precepts that will guide us in doing that.

Review

Last week we finished talking about the precepts for aspiring bodhicitta so that it doesn’t degenerate in this life, and it doesn’t degenerate in future lives. Then we started with the precepts of engaged bodhicitta where we have 18 root and 46 auxiliary. We started on the 18 root. It’s very interesting that as we look at these, to see which ones are related to each other and also how they are related to the ten non-virtues. Because many of the ones in here are pointing out specific ways (for example that we lie) that are detrimental, or specific ways (that we steal) that are really harmful. They still fall under the general rubric of the ten non-virtues, but here we’re creating downfalls of our bodhisattva precepts, which is much more severe than just the ten destructive actions or breaking our root pratimoksha precepts.

The precepts of engaged bodhicitta

To review what we did last time we finished four and we were on five.

The first one is,

Praising yourself or belittling others because of attachment to receiving material offerings, praise and respect.

This one could be a branch of lying if we praise ourselves with qualities that we don’t have or blame others for qualities that they don’t have. It’s definitely a form of divisive speech, because we’re trying to get offerings and respect for ourselves. It’s also a form of harsh speech if we’re saying it and the person we’re saying it about is nearby and hears.

Number two,

Not giving material aid or not teaching the Dharma to those who are suffering and without a protector because of miserliness.

This one doesn’t strictly fall under one of the ten, but it’s almost like stealing in the sense of protecting something that needs to be shared. Being stingy about something that needs to be shared with others.

Number three,

Not listening although another declares his or her offense.

That could be harsh speech or divisive speech. And then the other one, “With anger blaming him or her and retaliating.” That one doesn’t have to be in response to an apology. It could also be when in some situation we want to blame somebody for something and retaliate for something that they did. So it’s not necessarily that they apologized and then we’re blaming and retaliating. This one, depending on how we retaliate, could be a branch of the first one. We may not kill the person but we may strike them. It could be harsh speech.

Audience: [Inaudible].

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Yes, that’s mental actions. So definitely that would be involved.

The second one, “Not giving material aid” would definitely have covetousness, the mental action of covetousness involved with that one.

And then four,

Abandoning the Mahayana by saying that Mahayana texts are not the words of Buddha or teaching what appears to be the Dharma but is not.

This one, I suppose somebody could do it by lying and they could do it simply by ignorance out of wrong views. Or they could do it by arrogance and they want to establish themselves as some big professor about this or that so saying the Mahayana texts are not the words of the Buddha.

And then of course, teaching what appears to be the Dharma but isn’t. You may take some theme of what the Buddha’s talking about but you twist it so that it agrees with your ideas. Very easy to do, actually.

Audience: [Inaudible].

VTC: Yes, it also becomes idle talk, definitely.

And this is how the Dharma degenerates. Especially by people who are supposed to be teaching the Dharma, [instead] teaching what isn’t the Dharma. The degeneration of the Dharma…you may have like in India you had tribes and armies destroying the monasteries. But beyond that, the real degeneration happens when the Buddhist community itself does not uphold the precepts or uphold the teachings and kind of twists things around.

Then five,

This one’s clearly stealing, probably motivated by covetousness. Things belonging to the Buddhas could include clothes, jewelry or money that was offered to the Buddha, to a Buddha statue, offerings, food offerings or whatever. You walk past the altar and you feel like eating something so you take it off. Lots of people do this. I’ve seen them do it.

Or things that belong to the Dharma, again it could be cloths to wrap the Dharma texts in, it may be somebody donated the cloth for the Dharma texts, but you think it’s a beautiful color and it should be used for robes instead, that’s stealing it from the Dharma and using it for people’s individual things. We have to be quite careful when people offer something for a specific purpose. Of course, if you’ve used all of the cloth and you have just some fragments left, that’s something else. But here it’s totally redirecting the offering.

Or taking the possessions of the Sangha. Here the Sangha could mean one person who is an arya or it could mean a community of four or more fully ordained people. That’s what the Sangha means here. It doesn’t mean just one ordinary monastic. But especially with the community, and like I said before, this one gets very difficult to purify because you may return what you took but in a community some of the people who were there when you took it aren’t there when you return it.

That’s why we have an agreement that when guests come, we offer them tea, we offer them meals, that’s our agreement and we all know that we can be generous in that way. Otherwise, if we don’t have that kind of agreement, and we want to give some food to our friends who are lay people or give something that belongs to the community to the lay people, but we haven’t consulted with the whole community, that can be taking things from the Sangha. That’s why usually you do a sanghakarman, when the Sangha community is making decisions on what to give away. We have some things we agreed to beforehand, let’s say regarding the gifts in the closet, that if we were the one who put it there we can take it if we want to give it to friends, or we can take anything there if we want to give it to somebody on behalf of the community. Like when you’re going to Taiwan to ordain or we give gifts to sometimes different benefactors, to the people at the retreats and so on.

But if there’s something that we want to give to a friend or to a relative, we can’t just go into the gift closet and take what we want. Or take what we want from the toiletries and things like that. We do have a policy that when we have extra toiletries and so on, the person who is in charge of keeping things tidy in storage collects them and we take them to YES. But we don’t take things that belong to the Sangha community and give it to special friends or special benefactors, especially with the intention to curry their favor or something like that. These kinds of things are very easy to go beyond because you just think “oh, that’s a perfect gift for my friend, and I’m in a hurry,” and you just take it and don’t ask the community.

That also pertains to giving away food. Again, we have a policy. If guests come we offer them food. But we don’t give them the food that was offered to the Sangha for the Sangha for them to take home and share with their families, unless we’ve consulted the community and we know that it’s okay with everybody. Or it’s something that’s going bad that very day so you ask the person who’s in charge of the kitchen if it’s okay to give it, but other than that we shouldn’t just go in and, “oh, I know so and so likes this so I’ll give them this and that.” Because it’s food that was offered to the Sangha. Of course we want to be friendly to guests so that’s why we have this policy.

The sixth one,

Abandoning the holy Dharma by saying that texts that teach the three vehicles are not the Buddha’s word.

This is similar to the fourth. The fourth is talking specifically about Mahayana texts. This is much broader and it relates to texts that could be fundamental vehicle texts or Mahayana texts, they could be texts that are talking about the hearer’s vehicle, the solitary realizer vehicle or the bodhisattva vehicle. We look at these and we say, “This is not what the Buddha taught.” Again, very dangerous. And this comes when people may not agree or may feel uncomfortable with a teaching. The thing I always use as an example is people who say “Well, the Buddha didn’t teach rebirth,” when he very clearly taught rebirth. You may yourself personally be agnostic about rebirth and not sure how you stand. That’s fine. Take your time. Think about it. You don’t have to commit to believing anything. You check it out over time. But simply because it’s not your favorite teaching or it makes you feel uncomfortable, don’t say that the Buddha didn’t teach it. You could feel uncomfortable maybe about some of the bodhisattva practices, you hear that at some point on the bodhisattva path we give our body. And we don’t like that idea of giving our body, and sometimes when we don’t like something and we don’t want to give something up, how do we deal with it? We say, “Well, the Buddha didn’t teach it or that’s impractical, that’s stupid,” something like that.

The seventh one,

This one has two parts. With anger,

Depriving ordained ones of their robes, beating and imprisoning them.

And the second part is,

Causing them to lose their ordination even if they have impure ethical conduct.

For example by saying that being ordained is useless.

Let’s go back.

Depriving ordained ones of their robes, beating them and imprisoning them.

This is something that someone with political power could do. Let’s say the king that Nagarjuna was talking to, maybe he says he’s following the Buddha, but he doesn’t like how some monks are behaving so he calls in his police and he has them go beat them or take their robes away telling them they’re no longer monastics, or imprisoning them. So in some way or another, harming the monastic community. This could be toward somebody with pure precepts and somebody with impure precepts, it doesn’t really matter. If somebody has a lot of transgressions, they have to purify within the Sangha community. At least in ancient times, it wasn’t for the government and the king to come in and do that. But now, I heard of a case at a Dharma center, where there was one monk and he was flirting with a young girl, about twelve. There was some talk that maybe there was some molesting going on, so in that kind of thing, in our culture, in our climate, do you deal with that in the monastic community or do you involve the secular law enforcement? What do you think?

Audience: [Inaudible].

VTC: Yes, I agree with that. In our day and age if you just try and deal with that within the community, like what the church did (except they didn’t deal with it very effectively), even when they try to, it doesn’t work. In our day and age, this is something that you would, as much as you don’t want to, have to call law enforcement about. They may come and imprison the person which is not what you want, but I think when you weigh the harm against one individual against the harm to the entire Sangha, you’re stuck with a less desirable thing. Both alternatives are not desirable because it would be nice to be able to deal with this solely within the Sangha, but I don’t think in our culture that would work.

Audience: [Inaudible].

VTC: Yes, you bring it up in the presence of the Sangha, the person gets admonished, you talk to them with kindness and you try and get them to purify but you have to get law enforcement involved.

Audience: If someone confesses something during posada, is there a responsibility of confidentiality, if somebody confesses something that is illegal, is there responsibility of confidentiality amongst the Sangha or is there a responsibility to report them?

VTC: I think if you look at it just from the viewpoint of vinaya, it’s confidential. It doesn’t get shared with other people. Sangha business stays in the Sangha. The person may have committed a sanghavesesa or even a parajika, so they’ll have to have some things that they need to do to make amends. Parajika they can’t, but for the sanghavesesa they can. But I think nowadays, if I’m not mistaken, there are laws that (you may know better than I do) if you’re counseling somebody and they tell you that they’ve done something illegal or they’re about to do something illegal, you have a legal responsibility to report it. I think teachers and counselors and I think clergy also.

Audience: [Inaudible].

VTC: Nurses, doctors, yes. And the idea is, I think why the secular law was passed, is to make sure that that harm is stopped or counteracted. Of course it would be horrible in a Sangha community to have to do that. But somebody needs to be held accountable for their own behavior. This is where the church went wrong. They don’t want one of their own to be punished and they say “the person can reform and we can talk to them so that they don’t do it again” or whatever. That didn’t work, that didn’t work. Some of these people many times abused, sexually abused people. In addition they didn’t want to bring shame to the church. As a Buddhist I can understand that. I wouldn’t want to bring shame to the abbey by reporting that somebody did something illegal and I certainly wouldn’t want somebody who is a student who you know you cherish, you don’t want them to experience harm. You would like them to be able to purify and so on. On the other hand, there’s the secular law to take into account the integrity of the entire Sangha community. And at this point, that I think is more important. The basic thing is we’re all accountable for our behavior and it’s not good to hide, to excuse somebody else’s accountability, difficult though it is.

Audience: I agree with that but I do see that it undermines the conditions for transparency.

VTC: Well, it makes it harder for somebody to confess because they know the Sangha is going to have to do that. But this is why they need to think about this before they do the action. If you know that it’s going to be really hard to confess and admit it, and you know that in your mind, that could help you restrain yourself. Because if you lie to the Sangha community about it, you’ve lied to the Sangha, you create even more negative karma. Then if the secular authorities find out anyway, you get something for lying and you get something for the offense and you bring shame to the Sangha. Sometimes it’s hard for us to be transparent and honest. It’s painful! It’s painful! But it’s best in the end.

Audience: Basically I was going to say what you said. I don’t think it undermines transparency because it’s such, I find it even on mighty small things, a strong deterrent to know that I have to go every two weeks and confess.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: So hopefully knowing that and also knowing that concealment is a flaw.

VTC: Um-hum.

Audience: And it’s a flaw for the individual and it would be a real fault for the whole Sangha. So knowing that internally I think, is actually a strong deterrent.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: Can you keep ordination?

VTC: If you’re already ordained and you haven’t committed a parajika, yes, you can keep it. You have Chinese and Tibetan monks and nuns who were imprisoned and kept their ordination. But the other part of this, causing them to lose their ordination is, for example this happened under the communist takeover in China, they forced monks and nuns to have sex together. Or they forced people to do things that would break their ordination. The people who forced them are committing this kind of thing. Of course they don’t have the bodhisattva precept so they don’t have a transgression. I don’t think the PLA had bodhisattva precepts or I don’t think Mao did. If they did, they would be transgressing this but if they didn’t, it’s still quite negative karma although it’s not a transgression of this precept.

Audience: I am thinking about, [inaudible] was sharing about Kumārajīva who was forced to disrobe.

VTC: He was? Okay, on his way to China but I think he became a monk after that again I believe. Because I don’t think they would have him translating so many texts if he wasn’t a monk. If somebody had the bodhisattva precepts and did that, it’s quite negative. That’s what it says here. It’s causing them to lose their ordination, forcing them to do something negative or telling them they have to give back their ordination even if they have impure conduct.

If they’ve transgressed a parajika, that’s another thing. Depending on which view you have, their ordination is in shambles. In the Dharmaguptaka, you still have to return it even if you commit a parajika. In the Mūlasarvāstivāda they usually say you lost the whole ordination with a parajika.

Another way people could cause somebody to lose their ordination is by saying that being ordained is useless. That one is something that could easily happen. Sometimes, like in the west, people don’t have a lot of respect for the Sangha, for the vinaya, and some of them say “Oh, monasticism is old fashioned.” If you say that kind of thing and you cause somebody to disrobe, that’s this kind of transgression. I think many people don’t realize how negative that is—when you cause somebody or force them to disrobe.

I think if somebody is on the edge, “Should I?” “Shouldn’t I?” on the verge of breaking their precepts but they haven’t yet, you want to encourage them as much as possible to remain ordained and to keep their precepts. At your wit’s end you may say something to the effect of “If you think you’re going to transgress them it’s better to give the precepts back before you commit a parajika.” But you would have to say that in such a way that you weren’t encouraging the person to give back their ordination.

In this situation, the person who wrote to me is somebody who is benefacting a young monk. The young monk just was not acting properly at all and I commented that chances are he will disrobe. I would never encourage that young monk to disrobe, I would encourage him to keep his precepts, but if he was on the verge of committing some really negative karma, I would counsel better to disrobe than do that action. So there’s a lot to think about here. Try and prevent problems from happening within the Sangha community. If you see somebody that’s like this monk I heard about, if somebody saw somebody starting to flirt with a very young girl, you should immediately say something to that person. But this is the kind of thing people don’t want to say to another person when they think that other person is doing something against the precepts. We do not want to give advice to other people because they may get mad at us. Right? So we keep our mouths shut. We don’t give advice. That way they don’t get mad at us. We don’t get in trouble but they may go on and really do something quite negative because of it. Do you see now why we need to give each other feedback? Because if we just tolerate bad behavior, it’s very easy for that bad behavior to get worse.

The eighth one,

Committing any of the five extremely destructive actions.

These are often called the five heinous crimes or the five actions of immediate retribution, because these five are so negative that after you die you immediately get reborn in the hell realm, so immediate retribution. Those are killing your mother, killing your father, killing an arhat, intentionally drawing blood from a Buddha by striking a Buddha or cutting a Buddha or something, or causing a schism in the Sangha community by supporting and spreading sectarian views.

Here you can see the first four are involved with the precept against killing or physical harm. The one about causing a schism in the Sangha could fall under lying, divisive words, harsh speech. It also falls under the sanghavesesa for the bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, so quite serious.

Now, what about your mother or father… they’re old, they’ve been sick for a long time, they are ready to die and they ask you to help them. No, you can’t do it. You don’t know if they’re going to be happier or more miserable afterwards. But how would that be if they were pleading with you? And crying. And saying “I’m in such pain and I can’t bear this.” Would you be tempted to say, “Well you call the doctor and arrange it with the doctor?” No, in our monastic precepts you can’t even encourage death.

What about if somebody is going to have a child that is very badly deformed or may not even live? A child with zika or with, what’s the one where they don’t have a top to their head and the brain is (signals opening in head).

VTC: Somebody is going to have a baby like that and they say I want to get an abortion. What do you think?

Audience: You tell them that whatever time this little being has in this life is an opportunity for them to receive all this love and care and just go with that route. That’s the karma of this little being.

VTC: Yes, but it’s difficult for parents. So difficult in that kind of situation.

Audience: My question is now that people have advance directives, and I know my mother does, so do I, about not resuscitating, not being on a machine. “I don’t want to live in a vegetative state so you have to disconnect the machine” and so forth. What if we happen to be in charge of that whole scenario at that point and if we go by their wishes, are we committing a fault?

VTC: Your relative has an advance directive and you are the legal power of attorney. You know hospitals better than I do, if the advance directive is in the hospital, do they need permission from a relative to carry it out or are they legally bound to carry it out if it’s . . .

Audience: When somebody has an advance directive and brings it into the hospital, if that person is “coded”, their heart quits beating, on the chart it’s very clearly designated that this person is not to be resuscitated and so you don’t.

VTC: Yes. What about if it’s one where somebody is in a vegetative state and you say “two doctors have to agree before the plug is pulled?” Does a relative have to get involved with that or does the hospital carry that out?

Audience: No, the physicians would always bring in the family in that case. It would be like somebody with a severe head injury and it seems like maybe they’re gone, never going to wake up, never going to come back so then you get the experts in there to make the decision and they present that to the family.

Ven: Chodron: Even though the person themselves said that “If I’m in that state I want the machine to be unplugged?”

Audience: It kind of depends on where your advance directive is and where these things happen, it can be two different places. You’re in a bad car wreck somewhere, you go to the local hospital, they put you on life support and they find out later that you have an advance directive that says “I don’t want to be on all of that.” They take them off but they always have the family’s support and are okay with that. But it is a legally-bound document that they have to do but they don’t.

VTC: But if you were a family member in that situation, if you weren’t the one who had the power of attorney you could just step back and say “I don’t want to get involved in this decision.”

Audience: Yes.

VTC: I would say be careful who you choose to be a legal power of attorney for. Really think about that quite well and make sure that person puts their advance directive in the local hospital and that also you have a copy of it at home so that if they’re somewhere else you could take that copy to them.

Audience: Their willingness to follow that also might depend on where they are, because we certainly had that situation with my mother in Georgia.

VTC: Hmmm.

Audience: That was very clear, everybody on the team knew that she had a DNR but it was inconclusive about whether she would ever wake up or not. So when her heart started to stop in the middle of the night, there was a team ready to put those paddles on her.

VTC: Hmmm.

Audience: Everybody knew it but they were still going to resuscitate her so, this was a little bit dicey for me but I called her husband because he was the one who had the (directive) and I said “you need to get the directive about how these people should respond to her care.”

VTC: Yes.

Audience: And they accepted that but they would not follow through with it based on her wish alone.

VTC: Wow!

Audience: They didn’t know for sure where she was, it wasn’t clear whether she was going to recover or not but there was a DNR on the thing and actually they were quite clear, they were just making sure that we were clear. That’s kind of where that was at so it was a dicey situation.

VTC: Hmmm.

Audience: The person you had the DNR for is in the hospital dying but you hold the physical DNR, they don’t know that they have a . . . it’s a DNR.

VTC: I see.

Audience: You as a monastic do know.

VTC: Okay, do you bring it in and that may hasten the person’s death.

Audience: Yes, that’s my question.

VTC: Yes, actually, yes. We’re all in that.

Audience: When I’ve been involved with that kind of thing, what happens is they, kind of like what you talked about, get the family involved in and they get everybody on the same page. They get the best information they have about will this person ever recover or not and then all agree so it’s a group agreement kind of thing.

VTC: But I think her thing is also in that situation, because that is the situation. Let’s say somebody here has a stroke or a heart attack, we have everybody’s advance directives here and we know, we can read it, we can see which people say “I don’t want to be resuscitated” or “I don’t want to be put on a machine,” or “I want to be taken off” or whatever they’ve written. Do we bring that in with us when we go to the hospital with the person? Let’s say they didn’t leave it in Newport and we have it. It’s kind of, are we more bound to carry out the person’s own wishes, even if that results in a shorter life for them, or are we more bound to not get at all involved in the shortening of somebody’s life?

Audience: You know the problem with this is that you can keep a body, a corpse frankly, on machines for really a long time, but they are not there anymore. That’s the difficulty of this.

VTC: Really, how long have they been on life support?

Audience: Could be for years.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: The other point is that if we’re involved in an advance directive, it is really mandatory that we tell our physicians and our caregivers. When I travel I keep it on my person.

VTC: Yes, I do too.

Audience: So that as best as it can be, it’s known. Because if it’s known at the beginning, that is so much more helpful. It’s easier on everybody.

VTC: Yes, easier on everybody.

Audience: [Than] after somebody has been put on life support.

VTC: But I know with you, I would like you to respect my wishes, because I’d much rather die naturally than be put on a machine or pumped full of morphine or whatever. But I don’t want to put you in a difficult situation. Actually I’ve given mine to the Newport hospital but if somewhere I’m traveling they can call you and you have it here.

Audience: Our ICU nurse helped us a lot with that from her point of view. I had to deal with this myself of course, because I have this precept. But from her point of view my mother had already made the decision, there was no decision for anybody else to make. It was “Do we want to fight it?” or “Do we want to honor my mother?” Put in those terms and as I thought about it I felt that’s really true. She made that decision so none of us would have to and so it’s not mine to make.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: What would be the point of us making an advance directive if you’re just going to ignore it?

VTC: Right. We all have advance directives here. So you’re going to have to make one and you too, it’s part of what we do.

Audience: If something happened to somebody here do you get their family involved?

VTC: Do you get their family involved? I would say it would depend on who it was and hopefully you know enough about the monastic and their relationship with their family that you would know whether they would want it or not. Hopefully they’ve written it on their advance directive somewhere, whether “Call my family” or “Don’t call my family” or whatever it is. I think it’s much better if people write that down or “Call my family after I die, don’t call them beforehand.” It’s a complete gift to the people around you if you state what you want and they don’t have to decide.

Audience: My aunt was in a coma for I think, about a year and a half and they kept her alive against hope, really. And she came out of that and she’s still alive today and this was in the ‘80’s. She’s in a wheelchair, she has trouble speaking but I think through the years it’s become more and more evident that she’s not so much cognitively compromised as she is unable to communicate. She’s more there than people thought.

VTC: Hmmm. Yes. And I know Thích Nhất Hạnh, was in a coma for like three or four months? Something like that, I don’t know. It’s all kind of mysterious. What happened? Did she all of a sudden one day wake up or was it a gradual thing?

Audience: I didn’t know her very well and I was probably in high school then so I’m not sure of the details. But she came out of the coma and when I got to know her she was in a wheelchair and it was hard to understand talking with her and stuff. But it became evident through the years who she would recognize and that she was understanding what she was being told, that she might not be communicating well.

Audience: Just asking: what if taking the person off life support was the most compassionate thing at that time in that it would prevent more suffering, at least physical suffering?

VTC: Well, the difficulty with that is you don’t know if it’s preventing more suffering because they’re going to be reborn. It ends the suffering of this life but Lama used to say, unless you have clairvoyant powers and you know where that person is going to be reborn and that they’re going to have a happier life, euthanasia is really not recommended. That’s the thing, we look at it as only suffering from this life, but if we believe in rebirth, who knows where they’re going to be reborn and what they’re going to experience there. Very difficult. That’s why, really ask the people you’re close to to make advance directives.

Audience: A few years before I came here, I was working in an elderly center, as a care aide, and the one lady went through euthanasia. She asked her girlfriend to help her to die. And I remember the stress around all of that story at the hospital, at the center, and how yucky it was, it was really yucky, not nice. The nurses who were working there when she died, she had a very difficult death, it was painful for the people being around her, seeing that. Anyway, I remember it was an awful experience for everybody.

VTC: So they didn’t help her? She asked them to help her die but nobody helped her or they did help her?

Audience: Her girlfriend helped her.

VTC: Helped her but she had a very painful death anyway.

Audience: Yes. And there was a lot of controversy about it. The center didn’t want that to happen, and she wanted it, they did it illegally. It was not legal to do that and imagine her friend, the trauma she stayed with and she died with pills, they overdosed her and it was not nice apparently.

VTC: Yes. Very uncomfortable for everybody. Now, that’s why there’s some bills now for physician-assisted suicide so that somebody could say beforehand they want that or even at the time they want that. But then the doctor is not obligated to do it. You couldn’t legally force doctors to do that. But I know somebody whose father wanted to die and asked the family to help. The family helped and got him the medicine and the whole thing and I thought, “wow, you know, it’s killing your father even though he wanted it,” that would certainly mitigate the karma…

Audience: That’s like the monks that asked “please kill me,” you know at the time of the Buddha? Same thing?

VTC: Right, exactly. Yes. It’s very similar to that precept. Even if somebody asks you “please kill me,” then you don’t.

Audience: It’s legal in the state of Washington, and I have a friend who is a volunteer in assisting people, he feels very strongly that that’s a right thing for people and there’s no dissuading him from that. He feels like it’s a compassionate act, so it’s just like [inaudible], this view is quite different.

VTC: Yes. It’s very different. I know my brother wants that if he ever gets incapacitated and I’m not touching that one.

Audience: I know a woman who was taking care of her mother that was dying. Her mother was dying a very slow painful death. She was the one taking care of her so she suggested to her mother “I could give you a large dose of this morphine and you just wouldn’t wake up.” And it was not her mother’s wishes. Her mother was a strict Christian who believes that if she commits suicide then all of her devotion through the years is shot. And so that really disturbed her mother’s mind. She didn’t trust her. It was an odd situation and I think this woman was just very frustrated. Her mother was in a lot of pain.

VTC: These situations are so difficult. So often when we experience pain from watching other people being in difficulties and experiencing pain, we just want something quick so that the whole thing ends and goes away. That’s not really according to the precepts.

Audience: To me the sad part of this is that when people have the skill and knowledge about how to assist people through their death, it is really no problem frankly, it really isn’t. It’s if you know how to support and help people, people can bear pretty much anything. And it’s so sad when you hear a story like this that the person didn’t have any help and no support and the pain wasn’t managed properly and on and on and on.

VTC: Yes because now with palliative care the pain can be managed.

So that precept, difficult one? But we need to discuss this and think about it, especially in light of medical technology now. In ancient times, somebody was sick, they were dying, you just let them die. There were no machines to plug them into or take them off of or anything like that.

Audience: The medical professionals like the doctors and nurses, if they take these vows . . .

VTC: If you’re a doctor or nurse who has taken these precepts, how do you keep them? If somebody requests you for assisted suicide the doctor can say no. The doctor is not legally or in any way bound to go along with that. If the person has an advance directive, then it’s like you say, the doctor needs to legally go along with it, they may choose to get the family involved.

Audience: If they are following the orders of the patient and they’re the one that switches off the stuff, do they commit the karma?

VTC: Doctors I don’t think have to pull the plug if they don’t want to. If they feel uncomfortable, they can say “I don’t want to do this” and then somebody else does it.

Audience: You know, when a person is taken off a respirator, it’s because that person is gone. Most cases it’s quite apparent. And they do many tests and it’s quite apparent. Just like anything, there’s some cases where it isn’t so apparent, and those are the hard cases. Then it depends on the consensus of the group and what I’ve seen is that they err on the side of waiting instead of pulling and that’s why we have hundreds of thousands of people on life support in this country.

VTC: Yes. But I think as a medical professional if you don’t feel comfortable with doing a certain procedure because it violates your own ethics you can say “I don’t feel comfortable, I won’t do that.” And then the person has to go to somebody who does feel comfortable doing it.

Audience: Someone asked, what about injured animals, dogs, cats, deer.

VTC: Same thing. Same thing, better just to let them die naturally.

Audience: With the precept not to kill, I know that I would be breaking that if I pushed somebody in a river and they drowned, but to not dive in the river and save them is not breaking my precept if they already fell in on their own.

VTC: Okay, yes, if they fell in on their own and you don’t know how to swim very well, then it’s probably not too smart to dive in and try and save them.

Audience: Not trying to save the life is not the same as taking a life.

VTC: As in killing the life, yes.

Audience: So here we are talking about machines, trying to save a life like with resuscitation. A lot of this we’re talking about trying to save a life, or not trying to save a life, trying to save a life rather than killing somebody. There’s a difference there.

VTC: Yes. Right. But it’s good if you really know what the other person wants. That helps a lot. People need to talk with their families and their friends about this and write it down and so on. It’s very kind to everybody else involved to do that.

Audience: Before we go on to the next precept, actually I was wondering if you could talk about what is the definition of a schism in the Sangha, like must it be permanent? Is it like the two groups doing posada separately?

VTC: Schism in the Sangha is you have to have two groups of four or more fully ordained people who are quarreling and will not perform posada together. To the extent that they’re so divided… there’s a way where you can legally… and in vinaya things break up into two groups. But if you’re somebody who is, especially here, teaching a false doctrine and it’s not just being so angry that you don’t want to talk to those other people. It’s especially when you’re trying to set yourself up as the leader of a new group and gathering people around you to be part of your group and then causing that schism so that the Sangha is upset and angry and will not perform posada together.

Audience: Because I was wondering what with the whole Shugden issue, is that a schism?

VTC: That’s an interesting question. The issue in the Tibetan community over this one, I don’t know what you call them, spirit or protector or whatever. Actually, what happened is because the monks were all living together and there was so much quarreling about this that in the case of Sera, one group [comsan?] just moved out and started their own monastery down the road. In the case of Ganden, the one group [comsan?] is still right next to all the other ones but I don’t think they do posada together. That’s an interesting question, whether that is an actual schism in the Sangha, like that.

Audience: So, if you have say, four fully ordained monastics and they’re a Sangha that can perform the karma [confession]…

VTC: No, you would have to have the eight that break up into two groups . . .

Audience: I realize that but my question is if you only have four and that gets broken up, then it no longer functions. How come that’s not a schism?

VTC: Yes, but that’s not called a schism of the Sangha. If you only have a community of four and they break up into two, that doesn’t fulfill the definition. Because it has to be a group of four, at least four people that are breaking away.

Audience: Right, I guess what I am saying is that I don’t understand why because when, if a group of eight breaks up then there’s still groups that can perform posada, but if a foursome breaks, they can’t even perform their posadas anymore.

VTC: Right, that’s true. But if they’re quarreling and they split up, they can’t perform posada, they don’t perform posada because they’re in two groups. But the thing is taking a whole group away and doing a separate posada because you’re quarreling with that group. And especially not just like an average quarrel that “we’re just mad at you now, we don’t want to do posada with you now,” but it’s like they want to set up their own monastery and set somebody else up as their teacher and, like that.

Audience: I just wanted to clarify for myself, I heard another explanation that actually we can break this precept only if there is a Sangha at the time of the Buddha.

VTC: Right.

Audience: So what’s the difference?

VTC: Sometimes when they explain the five, they say that Devadatta was the only one because technically, it has to be a Sangha at the time of the Buddha that you split and so he was doing that. People who split the Sangha now don’t commit one of the five heinous actions. Still, you’re breaking a sanghavesesa, which is a very serious offense. Some people say it doesn’t matter if it’s at the time of the Buddha, some people say in terms of the five, that it was only Devadatta. Same for drawing the blood of the Buddha, some people say you could only do that at the time of the Buddha, not now.

Dare we go on to another precept? [Laughter].

Number nine is,

Holding wrong views contrary to the teachings of the Buddha, such as denying the existence of the Three Jewels or the law of cause and effect.

This is the same as the tenth of the ten non-virtues. Sometimes they define wrong views as denying the existence of something that does exist. Here the Three Jewels, the law of karma and effects do exist and you deny that they do. Some people say that’s the real meaning of one like this. Other people say it could also be asserting that something that doesn’t exist does exist. Saying that there’s a creator-God for example or something like that.

Here it’s much more in terms of something that does exist, that is a Buddhist tenet, and you say it doesn’t exist. In the other part of it, something that doesn’t exist and you say it does, to me, that would fall more under teaching what appears to be the Dharma but isn’t. So there’s no creator-God, there’s no cosmic mind, there’s no primal substance, but you say there is and you’re passing that off as Buddhism. To me that would fit in more with the fourth one rather than this one of wrong views.

Number ten,

Destroying a town, village, city or large area by means such as fire, bombs, pollution or black magic.

This is not so much you’re fighting a war and the war happens to be in the town and the town gets demolished. It’s specifically having the intention to damage that particular place. It’s not just “the army is passing through” or whatever, it’s “We want to destroy that town or that village,” or whatever it is. So by arson, throwing bombs, chemical warfare, poisoning people or black magic.

Now, this is interesting. What about Flint, Michigan? You have a high amount of lead in the water, it is damaging people’s health. I don’t know if it’s actually killing them or making them sicker so maybe they die earlier?

Audience: [Inaudible].

VTC: The kids. There’s a few different scenarios. You are an owner of a factory that is polluting things and you know it is polluting, and you don’t care and you don’t do anything about it, but it’s damaging people. Or maybe you’re a government official and you know this is going on but the factory owner is your friend and you don’t want to get them in trouble. Or maybe you’re a member of congress and the people who are representing that district are trying to get the feds to come in and stop it and you’re thinking, “Oh, you know, it’s extra expenditure, we shouldn’t have to expend money for that state to improve their water quality,” so how does that fit in with this? You don’t actually have the intention to kill anybody but you’re certainly being negligent and not protecting people.

Audience: [Inaudible].

VTC: It’s having the wish to destroy the town or the whatever so you have to have the motivation to actually destroy it. Here it’s really talking about the property. But if you’re making it uninhabitable, if you really dwell on the property and you know that you’re polluting, you don’t really care but you don’t have the intention to kill. That wouldn’t be a full one with this, but it certainly isn’t good.

Audience: [Inaudible].

VTC: Definitely with Japan they want to clean it up as much as they can.

Audience: Before that, when the whole thing wasn’t well-maintained, that’s why you get all these problems. So, then the negligence before that.

VTC: No, I didn’t get the impression that it wasn’t well maintained, it was that it was not constructed to withstand the kind of tsunami that happened. That’s the way I heard it. Did other people hear it differently?

Audience: [Inaudible].

VTC: Yes, it was an earthquake, but then there was the tsunami that came back that flooded the area.

Audience: I remember this clearly because I was following it then but there was a lot of denial from the Japanese government that there was the amount of radioactivity that was escaping or the level of damage that was done to the nuclear plant. It was really majorly covered-up for a long time.

VTC: Okay, yes. That’s a kind of negligence. They don’t really want to hurt the people, but they want to save their skin, they don’t want to look bad. It’s not definitely negative karma (but) it’s attachment to the eight worldly dharmas and letting other people suffer because of your attachment to your reputation.

Audience: When they build a nuclear plant, they’re taking that risk and really not being realistic about it, that they might destroy an area or harm a lot of people.

VTC: Yes. True, when we build anything we’re taking a risk because we don’t know what building is going to fall down. Nuclear plants are especially dangerous but then other people say it’s cleaner energy than, let’s say, coal.

Good discussion, I think this is quite helpful and has us all thinking about things and applying Dharma to the real world.

Contemplation points

Venerable Chodron continued giving commentary on the bodhisattva ethical code, which are the guidelines you follow when you “take the bodhisattva precepts.” Consider them one by one, in light of the commentary given. For each, consider the following:

- In what situations have you seen yourself act this way in the past or under what conditions might it be easy to act this way in the future (it might help to consider how you’ve seen this negativity in the world)?

- Which of the ten non-virtues is the precept keeping you from committing?

- What are the antidotes that can be applied when you are tempted to act contrary to the precept?

- Why is this precept so important to the bodhisattva path? How does breaking it harm yourself and others? How does keeping it benefit yourself and others?

- Resolve to be mindful of the precept in your daily life.

Precepts covered this week:

Root Precept #5: Taking things belonging to a) Buddha, b) Dharma or c) Sangha.

Root Precept #6: Abandoning the holy Dharma by saying that texts which teach the three vehicles are not the Buddha’s word.

Root Precept #7: With anger a) depriving ordained ones of their robes, beating and imprisoning them, or b) causing them to lose their ordination even if they have impure morality, for example, by saying that being ordained is useless.

Root Precept #8: Committing any of the five extremely destructive actions: a) killing your mother, b) killing your father, c) killing an arhat, d) intentionally drawing blood from a Buddha, or e) causing schism in the Sangha community by supporting and spreading sectarian views.

Root Precept #9: Holding distorted views (which are contrary to the teachings of Buddha, such as denying the existence of the Three Jewels or the law of cause and effect, etc.)

Root Precept #10: Destroying a a) town, b) village, c) city, or d) large area by means such as fire, bombs, pollution, or black magic.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.