Determining to practice patience

Shantideva's "Engaging in the Bodhisattva's Deeds," Chapter 6, Verses 8-15

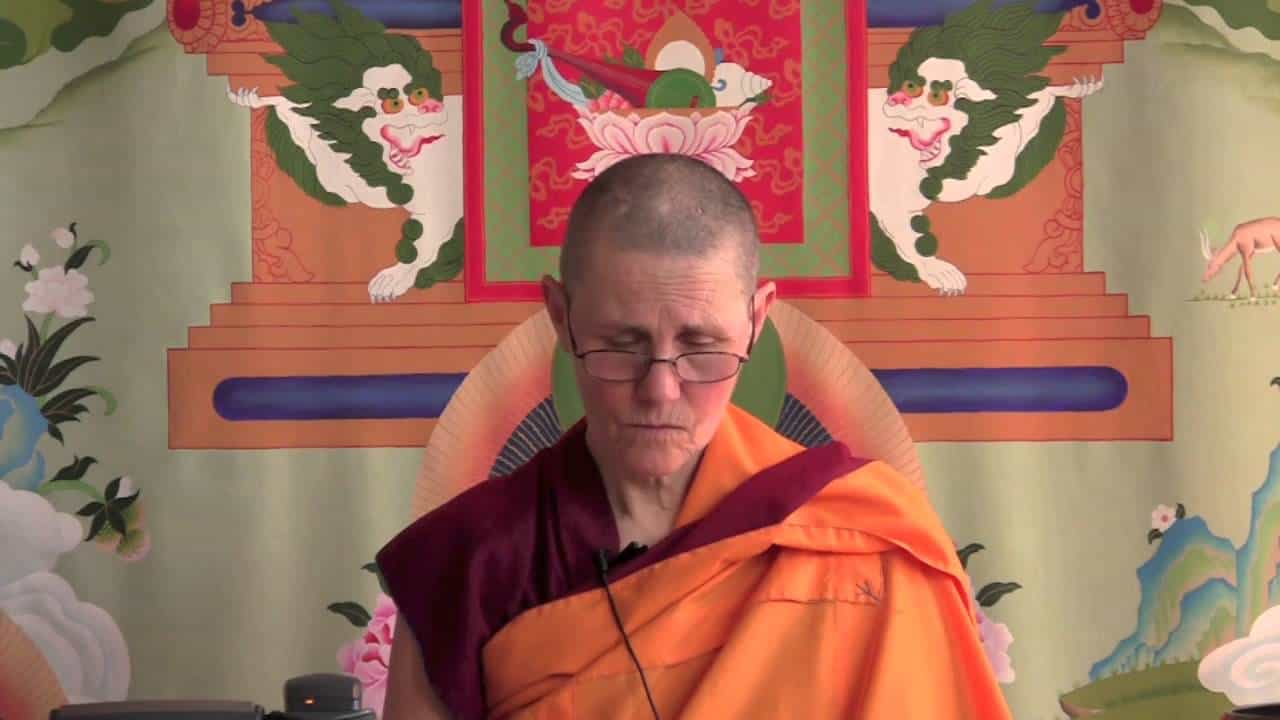

A series of teachings given at various venues in Mexico in April 2015. The teachings are in English with Spanish translation. This talk took place at Yeshe Gyaltsen Center in Cozumel.

- The ruminating mind and how it causes our unhappiness

- Making the determination to practice fortitude

- How anger is related to our bias towards friends and against enemies

- Four objects that we typically get angry with:

- Suffering

- Not getting what we want

- Harsh words

- Unpleasant sounds

- Reflecting on impermanence to diffuse anger

- The relationship between karma and suffering

- How suffering strengthens renunciation

- Lack of fortitude is an obstacle to our Dharma practice

- With familiarity, it becomes easier to endure sufferings

Let’s generate our motivation and think that we will listen and share attentively today, so we can clearly see the disadvantages of anger for ourselves and others as well, and develop a strong intention to counteract the anger, and then to learn and practice the methods to be able to do this. And we’re going to do this not only for our own peace of mind, but so we can make a positive contribution to society, and so we can progress on the path to full awakening and gain all the capabilities to be able to best benefit others. So, contemplate that for a moment and make it your motivation for being here.

Rumination is the cause of suffering

On the ride over here, we were talking a little bit about ruminating and how much that is the cause of suffering for us. There is a mental factor called inappropriate attention, and when we perceive an object, we look at it from the wrong perspective. We see it in an exaggerated way. In the case of getting angry, somebody says something and then we look at it and say, “They’re making fun of me.” That’s the inappropriate attention that is projecting, “Oh, they’re making fun of me.” Because “they’re making fun of me” does not exist in their words. Their words are just soundwaves. Those soundwaves touch my ear, I hear the sound, and then inappropriate attention says, “They’re making fun of me.” Or it says, “They’re trying to harm me,” or “They don’t like me,” or “They’re getting in the way of my happiness.”

This process of projecting a story and a meaning on somebody else’s words, this is coming from our mind, and sometimes we even mind-read: “I know why they said that. They said I looked really good in that dress, but what they really meant was, ‘You’re getting fat.’” Okay? Or, “They said they arrived late because there was an emergency, but I know that was one big fat lie.” We project that, and we’re mind reading their motivations. And we’re mind reading what we think they think of us. “They think I am so gullible that I’m going to believe that excuse. They disrespect me. They’re trying to put one over on me. They’re taking advantage of me.” All of this is coming from our side—mind reading their motivation—and then we think, “Well, then I better be angry!” Because any reasonable person when they’re treated disrespectfully and taken advantage of gets angry. So, my anger is reasonable, it’s valid, it’s appropriate, and everybody in the world should agree with me. Because I am right, and they are wrong.

That’s the way we see it. Okay? And then we continue to think about that again and again and again. We go through all the reasons why we know they don’t respect us. It wasn’t just the words they said, it was how they said it. It was that tone of voice. It was the look on their face. They may try to cover up their disrespect, but I can see it on their face. And you know what? Everytime they see me, they look like that. And every time I see them, there is some little lie that they tell me. I know what’s going on. And then, we call out the judge, the jury, the prosecutor, and in our mind we hold a jury trial and convict that person of lying and disrespect. This is all going on inside ourselves, and we do the trial many times, and the prosecutor repeats the reasons why the other person is guilty many times. And the jury says, “Right!” And the judge says, “Go get your revenge!” And then we do that, don’t we?

This is all happening inside ourselves, but we are so confused that we think this is an external reality, and then we become extremely unhappy. And then we become one of those people that the lady asked about last night who always tells their problems to somebody else, again and again and again. It’s the person who asks the other person, “What should I do?” but is not really wanting to hear any good advice because our ego is getting too much energy out of being a victim of this awful person. “Look how they are treating me! After everything I have done for them! What did I do to deserve this?” Do you hear those words? I got the whole routine down. [laughter] First I learned it because I heard my mother saying it, and you learn from your parents, so then I started thinking like that, too.

That’s not the kind of thing you want to teach your kids, is it? Yeah, but if we’re not careful, that’s what we teach them. So, the culminating point is, “What did I do to deserve this? I am the victim of the world! Everything comes down on me!” And what a great way to get a lot of attention. You know? “Give me some pity!” And then when you give me some advice, my mantra is, “Si, pero—” (“Yes, but—”). Every day I take out my mala and: “Si, pero,” “Si, pero,” “Si, pero.”

This is ruminating. The verse we stopped with yesterday was talking about mental unhappiness being the fuel of anger. And this is a very good example of it because we make our mind unhappy. So when my teacher, many years ago, said “Have a happy mind” and “Make your mind happy,” and I looked at him like, “What are you talking about,” this was exactly what he was talking about. So, that one was verse seven, talking about the mental unhappiness.

Destroy the fuel of anger

Verse 8:

Therefore, I should totally destroy this fuel of this enemy. This enemy of anger has no other function than of causing me harm.

This is what we just talked about: developing the ability to notice we’re ruminating and to press the stop button on the video. “I’m going to stop going around and around with the judge, the jury, and the trial—and the death penalty.” [laughter] We have to have some mental clarity and a strong determination to stop the ruminating. And this comes from repeatedly looking at our own experience and seeing how unhappy we are when we ruminate. And because we want ourselves to be happy then let’s stop doing the things that make us unhappy.

Verse 9:

Whatever befalls me shall not disturb my mental joy. Having been made unhappy, I shall not accomplish what I wish for, and my virtue will decline.

This is developing fortitude and making that strong internal determination that whatever befalls me shall not disturb my mental joy. You can see that it takes a lot of courage and determination to think like that, because at the beginning we think, “Okay, whatever negative thing befalls me it won’t disturb my mental joy,” but that negative thing is stubbing our toe or a mosquito biting us. But then we always hold out for the big things, like somebody at work talking about us behind our back. But those things really aren’t so big because people talk behind our back all the time. And who really cares what they say? “I care! I care! Because my reputation is so important. Everybody has to like me. Nobody can dislike me!” Nobody is allowed to say anything about me behind my back. Right?

Here we have to have this strong determination that whatever happens, we’re going to keep a happy mind, and if these little things happen during life—or even things that are little that we think are big—we’re going to keep firm and maintain a happy mind. Because if we don’t do this then we become so super sensitive to every tiny thing that happens around us. I live in a monastery with lots of different kinds of people, and you see this. Some people are so sensitive! For example, every day I give a talk at lunch time, a Dharma talk that we stream, and some days, I’ll give the talk and somebody will come up to me afterwards, and they’ll say, “You were talking to me, weren’t you? [laughter] That fault you were pointing out, you were talking to me.” And I have to say, “I’m sorry, you’re really not that important that everything I say happens to be about you.” But you see what happens when we have very strong self-centeredness? We perceive and describe everything in terms of ME and then create a whole story about it and then get unhappy.

This is the importance of having that strong mind that says, “I’m not going to get bent out of shape.” Otherwise, every small thing will bug us. I’m sitting and meditating in the hall and someone else is clicking their mala. Can you imagine the nerve of this person? Click, click, click. [laughter] I can’t concentrate because the sound of their mala is so loud. Of course, they’re sitting on the other side of the room, but that doesn’t matter, all I can concentrate on is click, click, click, click. Instead of rejoicing that somebody is creating virtue by reciting mantra, with each click, my anger increases, and at the end of the meditation sessions, I’ve got to stand up, go over to that person, and say, “Stop clicking your mala, for God’s sake!”

During one group retreat, there was a man who had a nylon jacket. You know how nylon jackets make sounds? He would arrive just as the session was starting, sit down, catch his breath, and then while everybody was meditating, he had to unzip his jacket. [laughter] People were complaining that the sound of the zipper was keeping them from concentrating. And then it was not only the sound of the zipper, but the sound of the nylon when he had to take the jacket off! It made it impossible to meditate! And it’s all his fault!

It has nothing to do with the fact that my mind is easily distracted. [laughter] It has nothing to do with the fact that there are zillions of sounds, but I’m focusing on that one. But it has everything to do with, “He is so inconsiderate! I’m sure he bought that nylon jacket before he came here just to bother me!” Okay?

Or you’re sitting there meditating, and the person sitting next to you is breathing too loud: “How can I focus on my breath when your breath is so loud! Stop breathing so loud!” And the other person says, “But I’m just breathing normally,” so you say, “Then stop breathing! Because your breathing prevents me from meditating.” We even had one person who had a roommate and said, “I can’t sleep because my roommate breathes too loud.” And the roommate wasn’t snoring or anything.

Do you see what I mean? When we don’t make this decision that we’re not going to let anyone destroy my mental happiness, then everything will disturb our mental happiness, and we will be the most irritable person around. And then we just complain because we’re irritated. We complain, we complain. We try to change the external situation to make it more comfortable for us, but we still complain about that. And it never ends, okay? So, that’s why we need this determination not to let our mental joy be disturbed.

Verses to remember

Verse 10:

Why be unhappy about something if it can be remedied, and what is the use of being unhappy about something if it cannot be remedied?

This verse makes a lot of sense, doesn’t it? If there’s something we can do to change the situation, there’s no reason to get angry about it because we can do something to change it. If there is nothing we can do about it, again there’s no reason to get angry because there’s nothing to do, and what’s the use of getting angry if you can’t do anything? It’s quite reasonable, isn’t it, what this verse says?

I think that some of these verses we should write on pieces of paper and put on our refrigerator door, on the bathroom mirror, on the center of your steering wheel. [laughter]. Okay? And then remember this: if there’s something I can do, no reason to get mad, and if there’s nothing to do, no reason to get mad. We need to remember these verses.

Verse 11 has to do with the kind of objects that give rise to anger. It says:

For myself and for my friends, I do not want suffering, contempt, harsh words, and unpleasant talk, but for my enemies, it is the opposite.

For ourselves and the people we are close to, that we like, we don’t want any suffering, either physically or mentally. And when suffering comes, we get angry. Your child took a spelling test, they’re in first grade, and the teacher had the gall to fail your child because he didn’t know how to spell gato (cat) correctly. You don’t want any suffering for your child or yourself, and anyway, if your child doesn’t know how to spell cat, it’s the teacher’s fault. If your child cannot get into a good university and have a good career because they failed their spelling test in first grade, it’s the teacher’s fault. Right? You forget that your child can also use spellcheck.

We don’t want suffering, and we get angry if we have suffering. And then here, the word “contempt” means not attaining gain, not getting what we want. When we want something, and we can’t get it, we get angry. “I want a promotion,” and somebody else got it. “I want to date that particular person,” and they’re dating somebody else. “I want—whatever it is we want—I want a certain kind of car,” but I can’t get that kind. We get unhappy, we get disgruntled, we get angry.

And then the third thing that makes us angry—although I shouldn’t say it makes us angry; we get angry all by ourselves—but the third thing we get angry at is harsh words. It’s somebody criticizing us, blaming us, accusing us—it doesn’t matter whether what they’re saying is true or not. “I don’t have any faults.” And even if I do, you’re not supposed to notice them, and even if you notice them, you’re supposed to forgive them. But on the other hand, when you have faults, out of compassion for you so that you can improve yourself, I’m going to point out your faults to you. Right?

But I’m not criticizing you, I’m doing it because I care. I’m doing it because I’m a Buddhist, and I’m practicing compassion. [laughter]. Okay, the fourth thing we don’t like is unpleasant talk. We don’t like somebody just talking and talking about the most boring stuff. Yeah? You’re in a car, on a long trip, with somebody who loves to talk about the history of golf. You would much rather talk about the history of shopping and all the latest bargains, but of course, maybe you’re somebody who gets bored when you’re in a car on a long trip with somebody who likes to talk about shopping. So, it’s just unpleasant talk. Or it’s somebody always complaining. These four things are things to pay special attention to because these are four things we easily have an unhappy mind about and then get angry about.

Suffering can also mean getting a cold. And then not getting what we want, harsh words, and unpleasant sounds. This is also like being stuck somewhere where they’re playing the kind of music that you think should not even be called “music” because the sound is so awful. Like when you pull up to a stoplight, and there’s some 18-year-old kid in the car next to you with this deep bass that’s going, “BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!” And your whole body is vibrating, but that person just thinks it’s the coolest music in the world, and the light just doesn’t turn green. These are things we get angry at, so let’s just pay special attention and again, tell ourselves, “I’m not going to get upset by this.” One way to help prevent getting upset is to remember that the situation is impermanent. It’s not going to last forever. Okay? There’s no sense getting mad at it because it’s going to disappear soon.

I remember many years ago when I lived in Dharamsala, one of my teachers Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey, was teaching us the 400 Stanzas by Aryadeva, and the first chapter is about impermanence and death. And so I would listen to the teachings every day and then go back to my room and contemplate them in the evening. During that time my mind was so peaceful because when I thought about impermanence and thought about death, it was so stupid to get irritated and angry at small, transient things.

At that time, my neighbor had a radio that she liked to play in the evening during the time I was studying and meditating and sleeping, but remembering impermanence helped me not to get angry. I just realized, “That sound is not going to last forever. Anyway, when I die, I don’t want to be thinking about that, so if I don’t want to be getting angry at that when I die, let’s not get angry at it right now either.”

And then the last line of the verse is really good, huh?

For myself and my friends I don’t want suffering—contempt, harsh words, unpleasant talk—but for my enemies, it is the opposite.

While I think those things are inherently negative in relationship to me and should be stopped, for my enemies they can have them. In fact, my enemies can go to hell for all I care. [laughter]. I mean, I know on Christmas cards, I always wrote, “May everybody be happy,” but that only pertains to people who are nice to me. The rest of them can go to hell! Right?

We’re among friends, we don’t have to pretend to be goody-goodys. [laughter] This is what happens when our mind is not balanced, when we have a lot of attachment and anger. This is a horrible analogy, but it fits. When the trains arrived at the gates of Auschwitz, there were guards who said, “You go this way to the gas chamber, and you go this way to the labor camp.” They decided who died and who lived. We have a little bit of that inside of ourselves, don’t we? “You’re nice to me, so you can have happiness. You talk about me behind my back, so you can go to hell.” And our self-centered thought thinks it has the right to determine everyone else’s fate. Correcto? We have some inner work to do, don’t we, to purify our mind? Yeah. But in the meantime, we also have to learn to laugh at how stupid our mind is sometimes.

It’s our karma

Verse 12:

The causes of happiness occasionally occur whereas the causes for suffering are very many. Without suffering, there is no definite emergence, no renunciation. Therefore, mind you should stand firm.

In the previous verse we noted that one of the things we get mad about is when we don’t get our way and when undesirable things happen to us, and this is talking about specifically how to work with our anger when the undesirable occurs. It says:

The causes of happiness occasionally come, but the causes for suffering are many.

Now, this isn’t referring just to external things, but it’s also referring to our karma as the cause of our happiness and suffering. We have some virtuous karma that creates the experiences of happiness, and we have negative karma that ripens into the experience of unhappiness. We always tend to be so surprised when we experience suffering because we always say, “What did I do to deserve this?” Well, the answer is we created the negative karma. But we don’t want to hear that answer. We want to think of ourselves as an innocent victim of the world’s injustice. Forget the fact that our suffering doesn’t even compare to the suffering of people in Syria right now, but we make such a big deal out of our own suffering. But it’s a result of our own negative karma.

Some years ago, I was telling a Dharma friend about a problem I had, and this is a real Dharma friend because he didn’t side with me against the other people, but he responded with a Dharma answer. We were talking on the phone, and I’m saying, “Oh, this happened, and they did this, and then this happened,” and my friend said, “What do you expect? You’re in samsara.” It was like somebody threw cold water in my face. And I stopped, and I said, “He’s absolutely right.”

Under the influence of my own negative karma, that I, myself created, why am I so surprised when things that I don’t like happen? It’s completely natural, especially when we get criticized. I don’t know about you, but I’m always so surprised when people criticize me because I always mean so well, and I always try to help people. And I’m a really good person, so I don’t know why these people are criticizing me. It’s really quite peculiar. But then when I think about it, and I look more closely, everyday I criticize at least one person. Maybe I criticize two or three. Maybe on bad days, I criticize ten or twenty. [laughter] And it’s every day that I’m critical of somebody, but I don’t get criticized every day.

Are you anything like that? Do you get criticized every day or do you criticize people every day? When you think that our experiences are the result of karma, the fact that we don’t get criticized every day but we criticize others every day is really unfair. And we’re getting off easy considering how much negativity we’ve created. When somebody criticizes us, really we shouldn’t be so surprised. All we have to do is look at our own mind. Correcto? [laughter] It’s saying, also, without suffering, we will never generate renunciation.

Consider the Three Principal Aspects of the Path as explained in the prayer by Je Tsongkhapa. What’s the first one? Renunciation is the first one. Bodhicitta is next, and then correct view. The first one of renunciation means that we renounce samsaric suffering. Without experiencing the suffering of samsara, it’s difficult to have strong renunciation, and this renunciation is important because that’s what pushes us to practice the Dharma and attain liberation and full awakening. One benefit of suffering is that it helps us generate renunciation.

Enduring suffering

Verse 13:

If the followers of Durga and the people of Karnataka endure the feeling of burns, cuts, and the like meaninglessly, then for the sake of liberation why have I no courage?

The followers of Durga and the people of Karnataka are non-Buddhists who often do very strange practices thinking that those practices lead to liberation. Sometimes they do a lot of ascetic practices, like not eating for many days, standing on one foot for many days, walking on fire, acting like animals. They mistakenly think they will attain liberation by doing these actions. Even though what they’re doing is meaningless, they still have so much fortitude to endure the pain of cuts and burns and heat and cold.

You would think if enduring those things brought something good, there would be some reason for enduring them and having fortitude, but they have strong fortitude, and it’s totally wasted. So then, looking at them, when I have the ability to practice the path to awakening, that is an unmistaken path, that will definitely lead to liberation, why have I no courage to endure unpleasant things?

What I really like about Shantideva’s teaching is that he talks to himself in this way and presents very good reasons to himself. So, here, it’s like, “It’s true. Why do I lack courage? Because if I endure even a little bit of hardship, it’s going to have a wonderful result. But whenever there’s a little bit of discomfort or inconvenience, I just become like a little kid. The Dharma Center is having teachings, but I have to drive a half an hour to get to the Dharma Center. Can you imagine the suffering that I experience driving a half an hour to the Dharma Center? So, I just can’t go. It’s too much suffering.” Of course, I drive forty-five minutes to go to work, but they pay me money, so I’ll undergo the hardship because that gives me the happiness of this life. But the happiness of future lives and liberation that Dharma’s talking about, yeah, I say I believe in it, but I don’t really live like I do.

Doing a daily meditation practice means I have to get up a half an hour early every morning, which means I can’t stay on the phone and gossip for an extra half an hour the night before, and I can’t exercise my thumbs for a half an hour, and I can’t space out watching a movie on the computer, and the suffering of getting up a half an hour early is just too great. Yeah? I need my beauty sleep. [laughter]. So, I sleep-in because I’ve got to be alert to go to work so I can make money!

Why do I have no courage? We always imagine ourselves—we want to be great Yogis, and we have all these great fantasies. “I’m going to find a cave and be like Milarepa and meditate day and night and actualize great bliss realizing emptiness and attain full awakening in that very life. I just have to find the right cave.” [laughter] Because it has to have a soft bed, and people have to deliver food to my cave every day because I need fresh vegetables. The cave has to be heated in the winter, air-conditioned in the summer, have running water and a computer so I can stay in touch with the world during my break times. But I’m going to be a great Yogi. And the cave has to have the kind of cookies I like, too. [laughter]. It can’t have the kind of cookies I don’t like because I have to meditate on the wisdom of bliss and emptiness, so I need the bliss from eating the cookies I like! [laughter]. We lack courage, don’t we? We’re trying to learn to laugh at ourselves and develop the courage that can endure these things.

Verse 14:

There is nothing whatsoever that is not made easier through acquaintance, so through becoming acquainted with small harms, I will become patient with great harms.

This is another famous verse. The verse that we talked about before—if there’s something you can do about it, do it, and if you can’t, also don’t get angry—that’s one famous verse. This is another one. What it’s saying is we have to get used to experiencing discomfort, and the more we get used to it, the easier it’s going to be.

The more we can get used to small things then we’ll be able to increase gradually and be able to bear bigger and bigger sufferings. I use this one a lot to help me because sometimes we do things while attempting to be of benefit to others, and they don’t appreciate it and they make our life very uncomfortable. Or sometimes to be of benefit to others, we have to undergo suffering ourselves. Okay? Remembering that it gets easier as you become familiar with it gives you some courage to not give up. Although I must say that flying on airplanes does not get easier because they keep making the seats smaller and smaller, and the people you sit next to keep getting bigger and bigger. [laughter] But you’ve got to start somewhere enduring suffering to develop fortitude, so that’s how I start.

I sometimes think of what the buddhas and bodhisattvas have had to go through to help me, and what my teachers have had to go through to help me. And then I realize that actually my suffering is not so great, and that if I really aspire to be a bodhisattva like my teachers, then I better get used to this because it’s not going to get better if I look at what they have to endure to help me.

Verse 15:

Who has not seen this to be so with meaningless sufferings, such as the feelings of harms from snakes, insects, hunger and thirst, and rashes?

Here it’s saying that you can get used to these small sufferings, such as harms from snakes, insects, hunger, thirst, and rashes. You can get used to those with time. We can see we get used to those with time, but then our mind goes, “No, I don’t. Getting used to the feelings from insects? I hate mosquito bites!”

Some of the things he’s saying are small things, but we think they’re big because in modern society we have so many creature comforts that we’ve never had to really experience much suffering. Whereas sometimes if we look at what our parents, our grandparents, had to go through, it was a lot harder for them. It was hot and there was no air-conditioning. It was cold and there was no heat. We’ve gotten a bit spoiled. I see this sometimes with Dharma in the West because when I first met the Dharma, there weren’t any centers where there were English speaking teachings, and I didn’t know any Asian languages, so I had to go halfway around the world and live in Nepal where they don’t have flushing toilets and where there wasn’t drinking water.

You should have seen the toilets we had at Kopan! It was a dug-out pit in the ground. The walls were bamboo mats, and there were two planks across the pit. In the dark, you had to be careful where you were walking! [laughter] There was no running water. The water had to be carried up the hill from a spring that was lower. Then there were problems of getting malaria, getting hepatitis, and diarrhea—with those fantastic toilets! Then you had Visa problems. You had food problems. And yet, we all went there, and went through whatever we had to go through to hear the teachings. In those days, the teachings were given in a tent, so again, it was just bamboo mats as the walls of the tent. The floor was dirt covered by bamboo mats, and guess who lived in the bamboo mats? Fleas!

You’re sitting there listening to Dharma teachings, trying to rejoice that all the fleas are getting good imprints on their mindstreams. Meanwhile, you’re going crazy scratching. And then, when Kyabje Zopa Rinpoche would give us precepts, you’re supposed to kneel when you recite the precepts, and so the position for kneeling was not very comfortable. In fact, it’s very uncomfortable. Rinpoche would tell us to kneel, and then he would give us the motivation for taking the precepts. And for any of you who know Rinpoche, his motivations are not short, so you are sitting there kneeling for one hour! “For the benefit of sentient beings, I’m going to take these precepts, please, Rinpoche, for my benefit, give them quickly! Because my knees are killing me!”

We just did it, but I find now, people coming to the Abbey, people coming to Dharma Centers, sometimes they think that it should be a resort! And they should get waited on hand-and-foot. You know, “I need this, and I want that!” But I really found that having to undergo some hardship for the Dharma was really worthwhile. It made you appreciate the teachings. And, of course, the suffering I went through was nothing compared to the suffering Lama Yeshe and Kyabje Zopa Rinpoche went through to escape from Tibet and come to Nepal. Yeah?

Okay, so I think there’s time for a few questions. You’re going to say, “I have to go to the bathroom. When are you going to stop! This is my suffering for the Dharma!”

Questions & Answers

Audience: Is anger something that we have learned culturally or is it a part of human nature?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): There’s two aspects to anger: one is called “innate anger,” and one is called “acquired anger.” The innate anger is the anger that has come with us from previous lives. It’s very deeply rooted, but it can be eliminated. But then the acquired anger is anger that we learn in this life. Sometimes we learn to dislike certain groups of people. We learn to dislike certain kinds of behavior. You can see, if you look at the situation in the Middle East, the hatred of different religious factions against each other. That’s all acquired anger. Because the babies didn’t come out of the womb saying, “I hate people from this sector or that sector.” That was learned. Again, it’s the wrong thing to teach your kids, but the kids were able to learn that kind of anger and prejudice because they had the innate anger in their mind streams.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.