Offering our help to all beings

Good Karma 10

Part of a series of talks given during the annual Memorial Day weekend retreat based on the book Good Karma: How to Create the Causes of Happiness and Avoid the Causes of Suffering, a commentary on "The Wheel of Sharp Weapons" by Indian sage Dharmarakshita.

- Commentary on Verse 8

- How the taking and giving meditation works

- Interdependence

- Commentary on Verse 9

- Confidence in the functioning of karma

- Purifying past actions

- Questions and answers

- The Dharma as preventative medicine

- Karma is not a reward and punishment system

Let’s remind ourselves of our purpose: we aren’t just seeking our own happiness of this life or even limiting ourselves to seeking the happiness of future lives or even our own liberation, but with a heart that is wide open, we want to become like the buddhas and bodhisattvas who are benefiting us so much so that we can benefit others in the same way. To do that, we need to tame our own mind and develop our own good qualities first. With that kind of motivation, to learn how to do that, we’ll share the Dharma today.

I’m going to try and do something unusual this morning and read. [laughter] I want to stop at a good place, so I would like to get through verse 9. But I’m not promising I will. I’m just stating an aspiration. [laughter]

Two objections to taking and giving

We were talking about the taking and giving meditation yesterday, and to continue with verse 8, it says:

People sometimes have objections regarding the taking and giving meditation. One objection is that it does not work. The other is that it might work. Regarding the first, we think, “I’m only imagining relieving sentient beings of their misery and giving them happiness. That doesn’t change their situation at all, so what is the use of doing this meditation?” Regarding the second, we worry, “What happens if by visualizing taking on others suffering, I succeed. I might get sick by imagining taking on others’ illness; I might lose my body, wealth and merit because I’m imagining giving them away.”

These are two “ifs, ands, and buts” that often arise regarding this meditation.

Our minds are so contradictory, and the self-centered thought is the root of the problem. Self-preoccupation does not want to waste our time doing something it considers useless, such as imagining others becoming buddhas. But it also doesn’t want to take a risk and possibly get sick if what we imagined actually happened. This occurs in so many aspects of our life: “Will I do this or will I do that?” We get totally tangled up and cannot make up our mind. We are stuck between two self-centered thoughts, and we cannot make a suitable decision or find a satisfactory solution.

These two objections to the taking and giving meditation are both fueled by the self-centered thought. The first one is, “Why should I waste my time doing something that doesn’t help others?” And the second is, “Well, maybe it will work, and I’ll get sick, and I don’t want that for myself.” They are both self-centered thoughts, aren’t they? This is an interesting thing to do in your life. Reflect on times when you’ve had decisions to make before and look at how the mind sometimes gets totally stuck between two self-centered thoughts because we want the most happiness for ourselves in this life, and we aren’t sure whether this decision or that decision will bring it.

Wise criteria for decision making

This even happens for Dharma practitioners. We’ve heard lots of teachings, but when we have to make a decision for ourselves, it usually comes down to “How will I benefit the most from this?” So, I’ll share the criteria I use for making decisions. Whether there are several decisions to make or just one—“Should I do this or not”—the first criteria that I use to make this decision is to question, “Will I be able to keep my precepts in that situation? Is this situation something conducive to living an ethical life, or will there be too many distractions or too many things that might trigger my old patterns that I’m trying to overcome?”

The second criteria I use is to question, “Will I be able to benefit others in this situation, or will I wind up in some kind of situation where instead of benefiting, I’m harming, or where I want to benefit, but there’s no door open or the other people are not receptive?” Along with that, I ask, “Is this a decision that will really help me to increase my aspiration to be free of samsara, bodhicitta, and the correct view of emptiness?” So, would this decision help in increasing my understanding of and experience of those three aspects of the path? I find that having this kind of criteria clear in my mind is very helpful when I look at different situations and figure out which avenue to go on. When you think like that, none of it is self-centered. As soon as the self-centered thought starts coming up, you can say, “You don’t fit the first, second or third criteria, so get out of here!”

Seeing the self-centered thought

We want to think of ourselves as magnanimous individuals who bravely relieve others of their pain and sacrifice our body, possessions and virtue for them. And yet, we don’t want to experience any discomfort.

So, we want to think of ourselves as kind, magnanimous people who will do anything for anybody, but we don’t want to be uncomfortable, let alone suffer. We don’t want any discomfort. But we want to think of ourselves as so open-hearted and kind and wonderful. Is that true or not true?

In fact, being aware of our discomfort when doing the taking and giving meditation lets us see the current limitations of our love and compassion.

For that reason, when stuff comes up, when the mind starts objecting to doing it, I think that we use that in our practice because we’re seeing very clearly how the self-centered thought says, “But, but but! I don’t want to suffer. I don’t want discomfort. I don’t want anybody to criticize me. I don’t want this; I don’t want that.” And here we are meditating on cherishing others more than self. And then we understand, “Oh, this is what the self-centered thought looks like.” And the thing is, it’s such a good friend. We have it with us all the time, and we don’t even notice it, so when our mind starts making a fuss regarding the taking and giving meditation, that’s the time to really see how that mind works.

With this knowledge, sincere practitioners will contemplate more precisely the drawbacks of self-preoccupation and the benefits of cherishing others to the point where they will become courageous bodhisattvas.

It’s easy to go through the list of the drawbacks of self-centeredness: “It makes me very ego-sensitive. It creates problems in my relationships. It makes me create negative karma that will ripen in a bad rebirth. It makes me unhappy.” Yeah, yeah. I’ve been through the list. I want to get rid of the self-centeredness. And that’s our meditation on the drawbacks of self-centeredness. It lasts at most forty-five seconds, and that’s why our mind rears up and says, “I don’t want to do this meditation.”

It’s really useful then to see, “No, I have to spend more time on this and not just give lip service to the self-centered thought being a big problem. I have to really explore that and make many, many examples in my life of how I’ve followed the self-centered thought and then wound up in a mess because of it. Until now, I’ve been attributing the mess to the other people in the situation, but now I see that the mess is due to the way I approached it and how I acted. I have to own that and then see that the self-centeredness is the real problem, the real demon in there.”

There’s one part of us that’s really reluctant to give up the self-centered thought because there is fear that if I don’t cherish myself above all others then what is going to happen to me? I have to look out for myself as number one; otherwise, everybody is going to take advantage of me. And then I’ll wind up as nothing and be just the doormat of the world. There’s that fear inside. But look at that fear. What are the assumptions that fear is based on? It’s based on an assumption that other people are mean and cruel and not to be depended on.

But we just did a meditation on the kindness of others and saw that we cannot stay alive by ourselves. Do you know how to grow your own food? Do you know how to make the cloth and then make clothes out of it? Do you know how to make the sewing machine? Do you know how to get the metal and plastic that are in the sewing machine? We can’t do anything to keep ourselves alive without depending on others. So, what is this thought looking at others and saying, “Don’t depend on them; they are to be feared”?

Maybe we’ve had a couple of bad experiences, but we’ve had zillions of good ones, so why do we focus on the two things that didn’t go so well? I’m not saying to have a Pollyanna view of the world, but I’m saying don’t go into things with an assumption that people are going to take advantage of you and harm you. Go into things with an open mind. Go in with a kind heart. If something happens then you revise how you act towards that other person. You may change how you act, but you can still maintain a kind attitude. Even somebody who is harming you is somebody who wants happiness and not suffering, and they are tremendously confused in this moment. If they weren’t suffering, they wouldn’t be doing what they are doing that is harmful.

In the two recent mass shootings, both with eighteen-year-old boys, do you think either of those kids was happy? Do you think they woke up in the morning and said, “I feel so good! I feel loved and cared for, and I really want to go out and play basketball or whatever it is with my friends”? No, those kids woke up that morning with incredible pain and suffering, mental pain and suffering. And they somehow, in the ignorance of self-centeredness, thought that going and doing a mass shooting would somehow make them feel better. Of course it doesn’t! The first one will be imprisoned the rest of his life, and the second one is already in the bardo. It didn’t bring happiness. But can we still have some kind of compassion for the plight they were in?

I do not use that as an excuse or as a way to blame. This is often the thing that people say: “Oh, it’s not guns. It’s mental illness.” No, it is guns, too. So, it’s really important to watch our assumptions and preconceptions and then sometimes in our meditation, when we’re visualizing the Buddha, to think, “What would it feel like not to have the self-grasping ignorance, not to have this reified idea of who I am? What would it feel like to be free of that? What would it feel like to be free of this self-preoccupation that worries about myself all day and all night?” Wouldn’t it be nice to be free of that?

Just right now, we can see that the self-preoccupation does not put us in a happy mood. It puts us in a defensive mood. So, think, “Wow, what would it feel like to be free of that? What would it be like to be free of anger? What would it feel like to be free of craving?” Just imagine that. Then we begin to have some sense of why self-centeredness interferes with that, and why cherishing others is conducive to being free of those other things. Then we want to cherish others.

And I think we have this inside us to start with, because if you look at children, as soon as they learn how to do things, they want to help Mom and Dad. It’s only later that they don’t want to help. Initially, they are happy to ask, “Can I help cut the carrots?” And we have to say, “No, because you are little, and you’ll cut your finger.” But the wish is still there to help cut the carrots and to set the table and to mow the lawn—to do all these different things. Kids want to join in. So, there’s that wish from the get-go, if we gave it a chance.

Taking and giving in our lives

We have to take a little intermission so that I can change the battery in my hearing aid. I don’t mind making a public display of having hearing aids because I think that too often in society, people accept glasses, but they don’t like hearing aids. And somebody will say, “Oh, your glasses are so nice,” but nobody says, “Oh, you have hearing aids now.” That’s somehow not polite. But what’s wrong with having hearing aids? It’s the same as having glasses but you have to change the battery in the middle of giving a talk. [laughter]

The taking and giving meditation is good to do when we experience fear and aversion toward our own suffering. It is also an excellent antidote to self-pity. When we feel hurt, we generally feel weak and helpless. To mask the discomfort of these feelings, our self-centeredness inflames our anger. Sometimes we may explode in anger, spewing our negativity on everyone around us.

Who has done that? Oh, hardly anybody here. But if I ask, “Who has been the victim of somebody else spewing their anger?” then all of our hands go up immediately. But maybe we’ve done that, too.

Other times we implode, retreating to sulk, pout and feeling sorry for ourselves.We have a pity party relishing the thought of “Poor me.” Our egos get a lot of mileage out of thinking we are victims who nobody appreciates. However, this thought only makes us more miserable, and our sulking and pouting only push people away from us at the very time when we most want to connect with them.

This is also true with anger, whether you implode and have a pity party and withdraw and not talk to anybody, or if you explode and splatter it all over the universe. What we’re really wanting at that time is to connect with other people. Do you really want to tell everybody off and make them go away? No. What you really want is to be harmonious with them and to get along with them. At that time, you don’t know how to do that, so you feel frustrated and that makes you explode or implode. But the real wish is to connect. This is especially true in families. We get more angry at family members than we do with anybody else. The people we care about the most are the people we dump on the most. Isn’t that kind of nuts?

But what we’re really saying is, “I want to connect, but I don’t know how at this moment.” And then our behavior pushes the other people away from us, because we either withdraw and refuse to talk to anybody or we blow up at them. In either case, there’s no chance for communication. We’re totally shut off, and yet, what we want is to connect. This is how the self-centered thought makes us confused and miserable. So, try and make some examples of this from your life. I could tell you many, many stories, but I’m really going to try and read. We’ll see how far I get.

Instead of drowning in this jumble of confused thoughts, we can do the taking and giving meditation.

When you’re confused like this, take on the suffering of others and give them your happiness. Even if you are furious at somebody, in that moment, think of their experience and what they are suffering. They have to deal with you when you’re acting like that. [laughter] Do you think you are a wonderful person when you are angry and slamming the door because you don’t want to talk to them, or when you’re screaming and throwing things? Do you think that endears you to other people? [laughter] No. So, when other people do that to us, it’s the same thing. They are expressing their frustration. The deep-seated thought is not to cause harm. The superficial thought maybe—“I’m so frustrated, I’m just going to blah!”—but underneath that, it’s, “Why am I frustrated? Because somehow I want to connect and live peacefully with these people, and that’s not happening right now.”

Taking and giving pulls us out of this unhealthy focus on ourselves and broadens our perspective to see that others are just like us, wanting happiness and not suffering. It elicits our love and compassion, bringing peace into our hearts and lives.

When we’re really upset about something we tend to go around and around, thinking about it and mulling it over and developing our strategy for how we’re going to act; we’re just going in a circle. I’ve found that in this situation it’s helpful to stop and ask myself, “Just on this planet, there are over seven billion human beings. How many of them are worried about this situation? One! Who is that one? ME!” So many other people don’t even know about it, or if they do know about it, because it’s not happening to them, it doesn’t stay on their radar. This works very well to calm me down. And I’m not going to tell you my story about it; I’m going to read. But I have a good story—next time.

Past causes and current results

We’re on verse 4 in chapter 9 now: “Understanding and Transforming Difficulties.” This is where the book begins to discuss the kind of causes we created in the past and what motivated us to create those causes: the self-grasping ignorance and the self-centered thought.

When my body falls pretty to unbearable illnesses, it is the wheel of destructive karma turning on me for injuring the bodies of others. From now on, I will take all sickness upon myself.

This is the verse that did me in. [laughter] My feeling really changed from “I should practice Dharma” to “I want to practice Dharma.”

This and the subsequent verses follow a similar structure. The first line describes an unfortunate circumstance we experience: we fall ill, our friends abandon us, and so forth. Sometimes we may feel that we’re the only person who has ever had that particular misfortune. The first line reminds us that whatever we’re experiencing is common to many people. The second line tells us that this unfortunate circumstance is not a random event but one caused by the destructive actions we have done in the past. It is the wheel of destructive karma returning on us. Contemplating this increases our confidence in the functioning of karma and its effects. By taking responsibility for our actions, even those done in previous lives that we cannot consciously remember doing, we stop blaming others for our problems.

You may think, “I don’t remember doing that thing in my previous life, and anyway it was a different person, so why do I have to experience the effects of what that jerk in my previous life did?” Don’t call your previous life a jerk. [laughter] It also got you a precious human life. But there is a continuity, just like there’s a continuity in our mindstream between when we’re infants and toddlers and children and teenagers and young adults and so on. There is a continuity there. What we learn when we’re young follows along with us. What happens at any time in our lifetime is something we learn from, and it goes on because there’s a continuity. So, there’s also a continuity in our consciousness from a previous life to this life.

The seeds of whatever we did, the seeds of our own karma, our own actions, come with us into the next life. We may not be able to remember what we did in a previous life, but if you think about it in terms of beginningless time then it’s pretty likely we’ve done about everything. We’ve had plenty of time in beginningless rebirths to do just about everything. We’ve experienced the highest pleasures in samsara, and we’ve also done the most horrible actions. We may not be able to remember all the happiness and all the misery, but those seeds are on our mindstream. So, it’s good to purify them now, even if we can’t remember doing them.

Put in the right circumstances in this life, we might do those things. We read the news, and we go, “Look what somebody did.” But there’s a whole stream of causal events from past lives and in this life that led to that person doing something. What would have happened if we had experienced that same configuration of causes and conditions? If you think of somebody that you can’t stand or somebody that you fear, think about what they experienced in their life. And then it becomes easier to have some tolerance for them. I do this a lot with politicians or other world figures, people who have a lot of power but who use that power to create suffering. If I had grown up as Vladimir Putin, in the circumstances he grew up in—if I had been a KGB officer for years and grown up in the Soviet Union like that—how would I think now? Maybe I would think somewhat like him. If I had grown up like Donald Trump, in his family or as whatever he was in a previous life, I could have wound up being like him, too. I find it very helpful to think like this instead of holding onto this idea that we have of “I’m an individual and I would never do that.” Well…

We don’t know, because we’re affected by causes and conditions, aren’t we? So, who knows what we could do.

By taking responsibility for our actions, even those done in previous lives that we cannot consciously remember doing, we stop blaming others for our problems. This reduces our anger and self-pity and stimulates us to reflect more deeply on our actions and their effects, both on others and on ourselves. So often our self-preoccupation prevents us from seeing that our actions affect others and ourselves.

We so often act without thinking of what the possible results are. And even when the results come, we don’t often think, “Oh, it’s because I did this and that.” We think, “It’s because that person did whatever.”

Changing old habits

A big part of our maturation as adults and as Dharma practitioners involves stretching our perspective and looking at the big picture. We must pay attention to the fact that our actions have an ethical dimension. Thinking deeply about the law of karma and its effects will enable us to make some important changes in our behavior and personalities. We’ll begin to break old, dysfunctional habits and build new ones.

This is telling us that we can’t just say, “Well, I’m an angry person, and there’s nothing to do about it. You married me, so you just have to live with it.” No! We can change. And when we change, the situation around us also changes. This is very interesting to see in a family circumstance when you have family dynamics where people are just repeating the same behavior again and again with each other. This is called “Thanksgiving dinner” and “Christmas dinner.” [laughter] It’s where you know exactly what’s going to happen between this sibling and this parent, and it’s kind of the same rerun every year. However, when one person acts differently in that kind of scenario then the other person can’t act in the same way.

If somebody keeps throwing out the hook, saying things that are designed to hurt you, instead of responding with hurt, you can think, “Why should I get hurt? I’m not going to bite the hook.” They are throwing out a hook, but we don’t have to bite it. So, you don’t bite the hook, you totally ignore what they said, and then what are they going to do? Okay, I’m going to break down and tell you a story. [laughter]

Some years ago I did some small something or other that displeased my mother. I don’t remember what it was; we could have saved some money or something or other. So, she started saying the same thing she always did: “I thought you were such an intelligent person, BUT…” It always started out the same way. [laughter] Is this sounding familiar? “…BUT…then you said this or that or did this or that.” She was going on about this, and usually I would get really irritated and defend myself. I would say, “Mom, you’re making a mountain out of a molehill. It’s not such a big thing. Anyway, my brother did it before, so why am I the one to get blamed?” It’s always my brother’s fault. [laughter] No, really, it was. I was the oldest; it was so hard for me! And then they let him do whatever he wanted to do! [laughter] And that is the end of the story. No, I’m joking with that.

So, back to the story: she is going on and on, but this time I just said, “Well, Mom, you’re in a difficult position. I guess you just have a really stupid daughter.” And that ended it. She had nothing to say after that. [laughter] We went on to talk about something else. [laughter] I did not bite the hook. I just said, “Yeah, I guess you just have a dumb daughter. What to do…”

It’s very interesting in these kinds of situations to try a different behavior. I was having dinner one time with a friend and his family, and his mom and dad started arguing. You know how it is for people who’ve been married forty, fifty, a hundred and ten years. [laughter] They review the same arguments. So, the mom and dad started something like that, and I interrupted and just changed the subject. I took one word out of what they were talking about and directed the conversation in a different way, and then dinner went on. Afterwards, my friend said to me that his mom and dad had had that argument so many times and he never realized that all he had to do was to change the topic. [laughter] He said, “You showed me a way to handle that.”

It’s true. When people start just doing the same old thing, you just throw a wrench in it, a subtle wrench. It’s not a wrench, like “You’re wrong!” You just steer the conversation in a different way.

No more “Why me?”

The third line of each verse describes more specifically what the action was. So often when we experience obstacles in our lives, we say, “Why me?” This line answers that question.

“Oh, why did this happen to me?” In other words, we’re saying, “I’m an innocent victim.” Well, the third line in the verse tells us what we did in the past.

While it may not be pleasant to recall specific destructive actions we have done, it is useful for it motivates us to purify the seeds of the destructive karma. If filth is hidden under a rug or behind a cabinet, we will smell it but won’t be able to do anything about it. Only when we see the dirt in a room can we clean it. Similarly, this line sparks us to look more closely at our lives, perhaps to even do a life review, acknowledge our harmful actions, and then purify them. The fourth line expresses a resolution to act in the opposite way in the future. The stronger our conviction in karma and its results, the more we will be motivated to apply antidotes to our disturbing emotions, refrain from destructive actions, and engage in constructive emotions, thoughts, and actions. We will then make the determination to act differently in the future, and to solidify this determination, we do the taking and giving meditation, taking on the misery of others and giving them our body, possessions and merit. Doing this increases our love and compassion and weakens our self-centered thought, thus enabling us to act according to our virtuous intentions.

So, we have to go back and review the instructions for practicing the taking and giving meditation, and we need to remember what the purpose of this meditation is and what this meditation is designed to help us feel. It’s also important to check when we do the meditation whether we are coming to the right conclusion. If we take on others’ suffering and then say, “Oh, I’m such a horrible person; I deserve to suffer,” that is the wrong conclusion from this meditation.

If we take on others’ suffering and say, “I’ve created the cause for this kind of suffering myself, so I’m going to purify it,” then we’ve reached the correct conclusion. It’s important that we always understand what the purpose of the meditation is, and then we check our conclusion when we’re meditating.

Verse 9 is the verse that affected me so strongly when I was sick with Hepatitis-A. ‘Our illnesses are the result of our destructive actions, in particular injuring the bodies of others.’ We may think I’m a nice person, I never killed anybody. We may not have killed another human being, at least in this life, but most of us have killed insects and perhaps animals as well. We may have gone hunting or fishing or asked someone to cook live shellfish for our dinner.

During my twenty-first birthday party, before I met the Dharma, my friends took me out to a seafood restaurant. It was a special occasion. At this restaurant they let you pick out the lobsters you wanted to eat, and they would take them out and drop them in the hot water and cook them right in front of you so you had fresh lobster. That was what my twenty-first birthday party involved. Like I said, that was before I became a Buddhist. After I got Hep-A, I thought about that birthday party, and I thought about what happened to that lobster. And I thought about all the flies I had swatted as a kid, all the snails I had stepped on.

Thinking we were putting a pet out of its misery, we may have euthanized it, or we may have sprayed pesticides in our house or garden.

Then everybody says, “But, but but—what do you want me to do instead of that?” Well, what we’ve done with our pets at the Abbey is we just take care of them until they die. We say mantras over them. They listen to Dharma teachings until they die, and we are with them when they die. We don’t euthanize. What did we do when that building, Ananda Hall, was infested with termites? [laughter] We took out the termites as best as we could and moved them somewhere else, so they could live happily ever after somewhere else. You do your best with these kinds of situations.

We may recall doing such actions in this life. Sometimes these are actions done in previous lives that we only infer we have done since we are experiencing this type of result. For example, perhaps we were a powerful leader of a country who led the people into an aggressive war.

I wrote this book at least a decade before Ukraine was invaded. It might have been during Afghanistan.

Even though we may not have killed anyone ourselves in this previous life scenario, we commanded our troops to take the lives of the enemy. By doing so, we accumulated the karma of taking the lives of many people. Or perhaps for the sake of solely scientific curiosity, we injected many animals with viruses just to see what would happen. We have had infinite beginningless lifetimes in which we have done every type of action. While we do not remember these actions, their imprints are on our mindstream, and when the cooperative conditions are present, that karma ripens. In the case of my Hepatitis, the cooperative conditions were the unclean vegetables.

The little monks, seven, eight and nine-year-olds, tried to wash the vegetables.

But the principal causes of my Hepatitis were my own actions in these previous lives. In situations such as illness, we can either get angry and depressed, or we can transform the situation into the path to awakening by thinking, ‘This is the weapon of destructive karma returning upon me. So, I’m not going to blame anybody else. I’m going to learn from this mistake. Since I don’t like illness, I must stop creating the cause.’

When we experience some unpleasant result, we can think, “I created the cause.” Look in this book or look in one of the other lamrim, or thought training, books about the kind of actions we may have done that led to that result. And then think, “If I don’t like this result, I have to stop creating the causes for it.” And then make a very strong determination to act differently in the future, and when you act differently then of course your situation in this life changes, and in future lives your situation also changes. So, we make the firm intention to not injure anybody else’s body ever again.

Planning for the future

At this point it is helpful to think about what we will do if we encounter a situation in which we may be tempted to injure others’ bodies in the future.

We make a strong determination that “I’m never going to do that again,” but we never imagine how we’re going to react in a situation where we’re tempted to do it again. It’s like if you weigh four-hundred pounds, and you’re trying to lose weight. And you say, “Okay, I’m never going to eat ice cream ever again,” but you don’t think, “What am I going to say when my friend offers to take me out to 31 Flavors?” Or, “What am I going to do when I’m in 31 Flavors next time with other people?” We don’t think about that. But we should because otherwise that attachment is going to come up, and we’re not going to only eat one scoop; we’re going to have four or five scoops. It’s important to really question, “If I’m in that situation, how am I going to think so that I don’t do the same old thing again?”

Do we put ourselves in environments where this could happen?

If you want to lose weight, are you going to go to 31 Flavors? Do we put ourselves in an environment where we are tempted to act unethically?

Even if I deliberately stay away from such situations, something could arise unexpectedly whereby I might be tempted to kill somebody.

This is in the context of the first precept. But similarly, if you have a substance abuse problem, are you going to go back and hang out with friends you used to drink and drug with? If you do, you could wind up drinking and drugging again. I think that’s one of the purposes of AA: it helps you develop new friends, and with the support of those friends, we don’t put ourselves in that same situation again.

How would I want to act in such a situation if I found myself in it? How could I subdue the anger or the fear that would cause me to take another’s life? We may want to spend some time meditating on fortitude in order to strengthen our determination not to succumb to anger or to contemplate impermanence to overcome the attachment that breeds fear. Meditating in this way prepares us to deal skillfully with such situations in the future. To purify destructive karma we may have created through injuring others’ bodies and to prevent harming them in the future, we do the taking and giving meditation.

This meditation is something that is going to be an antidote to what we’ve done in the past and to the tendency to repeat that action in the future.

Since this verse has to do with experiencing illness, with compassion we imagine taking on the sickness of others and using it to destroy the ignorance and self-centeredness that lie behind our having harmed others’ bodies in the past. Breathing in the pollution that represents their suffering, we think it transforms into a lightning bolt that strikes and demolishes the lump of ignorance and self-preoccupation at our heart. We tranquilly dwell in the empty space in our hearts, relishing that others are free from their illnesses and that we are free from our ignorance and our self-centeredness.

So, we take what others don’t want—their illnesses—and we use it to destroy what we don’t want—our self-grasping ignorance and our self-centered thought. And that’s the visualization with the lump at our hearts being destroyed by a lightning bolt or whatever you want to visualize. You could also visualize dirt at our heart and a Spic-and-Span that doesn’t pollute coming and cleaning it. Use whatever visualization you want.

Then we imagine transforming our body and possessions into medicine, hospitals, healthcare professionals, loving companions, and whatever else those suffering from illnesses may need or find comforting. Giving these to them, we imagine them healing and living happily. Giving them our merit, we think that they have all the necessary causes to meet and practice the Dharma. Through this, they progress on the path and attain full awakening. Imagining this, we feel satisfied and peaceful. This is the basic way of meditating for verses 9 to 44.

This is going to get pounded into us repeatedly. We need that kind of repetition.

If the verse deals with an experience you have not had in this life, think of what others have experienced. Also examine if you have created the cause to experience this in the future. We may have created the cause in this life but not experienced the result yet. Before the result comes, we should engage in purification practice by doing the taking and giving meditation as well as other practices, such as bowing to the Buddha and reciting the Vajrasattva mantra. Even if you have not done the destructive action described in the verse in this lifetime, make a strong determination to avoid it in the future. Since we never know what kind of situations we will encounter in this or future lives, where we may be tempted to do that action, making a firm decision now not to behave in such a manner is helpful to restrain ourselves in the future.

This is where imagining being in a situation where we may be tempted to do that and imagining doing something different is very, very helpful.

Making this meditation matter

Then do the taking and giving meditation. With each verse, the key is to think about the specific suffering and its corresponding causal action in relation to our own lives.

This cannot be emphasized enough. If you just think about it abstractly, it doesn’t have the same effect. We have to look at our own actions, our own life experience. We have to look at what we have seen our friends and family experience. We have to think about these specifics as it relates to our own lives. Otherwise, it all remains so theoretical, and it doesn’t hit us in the heart so that we start to really change. This is really the key: in our meditations, we have to apply it to our own lives. And then, the analytical meditations become really interesting. If you’re only doing it theoretically, like with the illustration at the beginning of how to do the meditation on the disadvantages of the self-centered thought in forty-five seconds, it’s not going to have an effect.

We need to look at our lives. For each verse, we need to ask, “Have I ever acted this self-centeredly? I know many other people have done that towards me, but have I ever done that towards other people?” At first, it may not be obvious to us, and then we start thinking about difficulties we’ve had with other people in the past. “Hmmm….did I have any part in that? What did I do?” [laughter] And then we start noticing the self-centered thought.

When we do that, then our meditation becomes very rich and meaningful, because we’re applying it to our own lives. Some of these circumstances mentioned in the upcoming verses and their karmic causes may be difficult to think about. They may challenge our image of ourselves or bring up regret that has long been buried. If this happens, go slowly, have compassion for yourself and for anybody else involved.

You don’t need to let it trigger all your afflictions again.

Be glad that you are now able to clean up the past. Learn from mistaken actions and go into the future with a kind heart.

It may bring up painful memories, and we may have done absolutely nothing in this life to bring that circumstance to ourselves, but we can think about the kinds of actions we may have done in a previous life that we don’t remember. There’s the continuum, and we’re experiencing the results from that. But also, in thinking about karma, look at all the good things going on in your life and remember that you’re experiencing those because of the virtuous actions you created in a previous life. None of us are starving to death. Considering the situation on this planet, with the blockade of the ports in the Black Sea, it’s risking food shortages, especially in Africa but also in other places where millions of people will be exposed to this situation. Russia is blocking the grain from being shipped out, and Ukraine and to some extent Russia, too, are the breadbaskets for many other countries. So, this is going to cause widespread famine.

Look at our lives. We don’t even think that there would ever be a famine here. There could be, and even if there isn’t a famine, how many people in our own country right now don’t have enough to eat? So, it’s important to think about things like this. “I have enough to eat. This is because I was generous in a previous life. I’ve never experienced war, or if I experienced war, I was able to get to a safe place away from the conflict. That is due to having created good karma in a previous life.” We didn’t die in the war, in the conflict. Go through everything we have going for us in our lives and realize that that, too, is due to virtuous actions. It’s not random.

That will help us also to appreciate the incredible richness we have in our life and the incredible opportunity we have to encounter the Buddha’s teachings and to practice them. We don’t just look at the bad stuff, we also look at the opportunities we have and say, “Wow, I did a lot of good stuff in many previous lives to bring about the circumstance I have right now.” And in that way, we encourage ourselves to create virtue.

Questions & Answers

Audience: I do strongly connect to the paragraph here that talks about if we have not created the causes to experience it or we have but we haven’t experienced the results yet. I go back to the analogy of the Three Jewels and the Buddha being a doctor or a physician, and sickness. I always try to see the Dharma as a preventative medicine. Sometimes I’m on the back end of already experiencing the suffering results, but to think in this way lets the Dharma become more alive. It’s like a medicine I can take to make sure these things don’t happen.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Yes, and that’s exactly what the Dharma is: preventative measures to help us so we can purify the karmas we created in the past so that we can create more virtue and so that we can get rid of this incredible self-centeredness and self-grasping. Because once the karma has ripened, we can’t purify it. Once you break your leg, you cannot unbreak it. You can heal from a broken leg, but you can’t unbreak it. So, once the karma has ripened and we’re experiencing the miserable result, we can’t make it vanish instantly. We can create more virtue that would help good cooperative conditions to come so that we can heal from whatever karmic results we’re experiencing. You broke your leg, so you can’t unbreak it, but we can help to create the causes to go to a hospital after we’ve broken our leg, to have a competent doctor, to have nurses who take care of us, to receive good treatment, to heal. And then we can create the cause to prevent breaking our leg in the future, such as not putting ourselves in dangerous situations. [laughter]

Audience: The other piece is that if the leg does get broken, to not kvetch or whine about it, and to really use it as a form of thought training.

VTC: Exactly. And especially if we’ve been kind of coasting along in our practice for awhile, we can say, “Oh, it’s good that I have some suffering now. It’s going to wake me up in my Dharma practice so that I stop taking things for granted and stop being a spoiled brat.” [laughter]

Audience: Karma feels like being punished now for previous actions in previous lifetimes. How does one not view it this way?

VTC: By realizing that it’s not punishment. Punishment implies that there’s somebody who is dishing out justice, and somebody who thinks, “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth,” which would leave everybody blind and without teeth. We’ve got to think about what the Buddha taught. He did not teach reward and punishment. That is not what karma is. So, if you’re thinking that it’s reward and punishment and feeling like you’re getting punished, then you have to go back and really do some studying on what the Buddha is teaching here. If you’re seeing everything as punishment then what about all the good things that happen? When we are suffering, we always say, “Why me?” When we eat lunch today, are you going to say, “Why me? Why should I have food when millions of people in this world don’t?” When we’re sitting here in a safe place, do we think, “Why me? Why am I sitting here with nice people in a safe place and other people are getting their homes bombed?” We always direct our attention towards the negative and leave out the positive. That worldview is very skewed. We have to change it.

Audience: How do you skillfully explain this karmic link between illness and harm done to others in previous lives in a way that prevents people who aren’t familiar with the whole Buddhist worldview from mistakenly attributing things like the AIDS epidemic as some kind of negative karmic outcome of the orientations and expressions of the people in the LGBTQ community who have disproportionately experienced and died from it?

VTC: Okay, I have learned from experience the disadvantages of trying to explain a horrible event to people who do not have an understanding of karma by explaining karma at that time. What I have learned from doing that is do not do that. Because that is not the time when people can take that in. It’s very detrimental, very harmful, at that time. What people need at that time is compassion, comfort, and support. And because they don’t know about the Buddhist worldview and past and future lives and karma and its results, they don’t know how to understand this in a way that is helpful, like what I’m teaching right now. And so they misinterpret it. I have made two big boo-boos doing that, and I’ll tell you my big boo-boos and how I learned that it’s not the right time, even if somebody asks you.

Do you remember when that plane that had a bunch of students from a Syracuse college crashed? It was shot down in I think a terrorist attack. Well, I was in the process of a prearranged tour to teach Dharma in different places, and one of the places already scheduled was that University. I was giving a talk a few weeks after that plane crash when it was still very fresh, and I opened it to questions and answers, and somebody raised their hand and said, “We just lost a lot of our friends and colleagues from this University to this terrorist action. How do you explain this in terms of karma?” I made the BIG mistake of saying, “Well, you know, when people experience an untimely death like this, it’s usually from having taken a life in a previous lifetime.” I will never say that again to people who are grieving. They got angry. They felt like their friends and relatives who were innocent were getting blamed. They weren’t getting blamed, but you have to understand the whole worldview to understand this properly. And these people are thinking just in terms of one life. So, do not explain karma at that time to them. Just offer compassion and comfort: “Yes, that was a horrible thing that happened. We never want anything like that to happen again to anybody.” You don’t answer their question directly. Usually, I think we have to really try and answer people’s questions directly, but in that circumstance, you give them what they need. You don’t give them the answer to the question because they don’t need that answer.

There are many situations in life where people ask a question but where giving the answer is not helpful. What they’re really saying when they ask a question is “I need comfort” or “I need to know that you care about me.” That’s their real question, so answer their real question. The other time I made this mistake was perhaps a bigger problem than the first example. I was asked to speak to a Jewish group, and as always happens, and I should have known better, someone said, “What about the Holocaust?” Me and my big mouth tried to explain karma at that moment. I will never do that again. That’s not what they need to hear. People are still suffering from that. You don’t talk about karma in terms of slavery to a group of people who are traumatized by slavery, especially when they don’t know anyting about Buddhism to start with. We have to be very sensitive to who we explain what to, especially when they are brand new to Buddhism. And it’s important to really listen to them. People may be asking one question, but what they are really saying is something else. We have to reply to the real question that they are actually asking.

I know. I did it twice! How could I have done that?

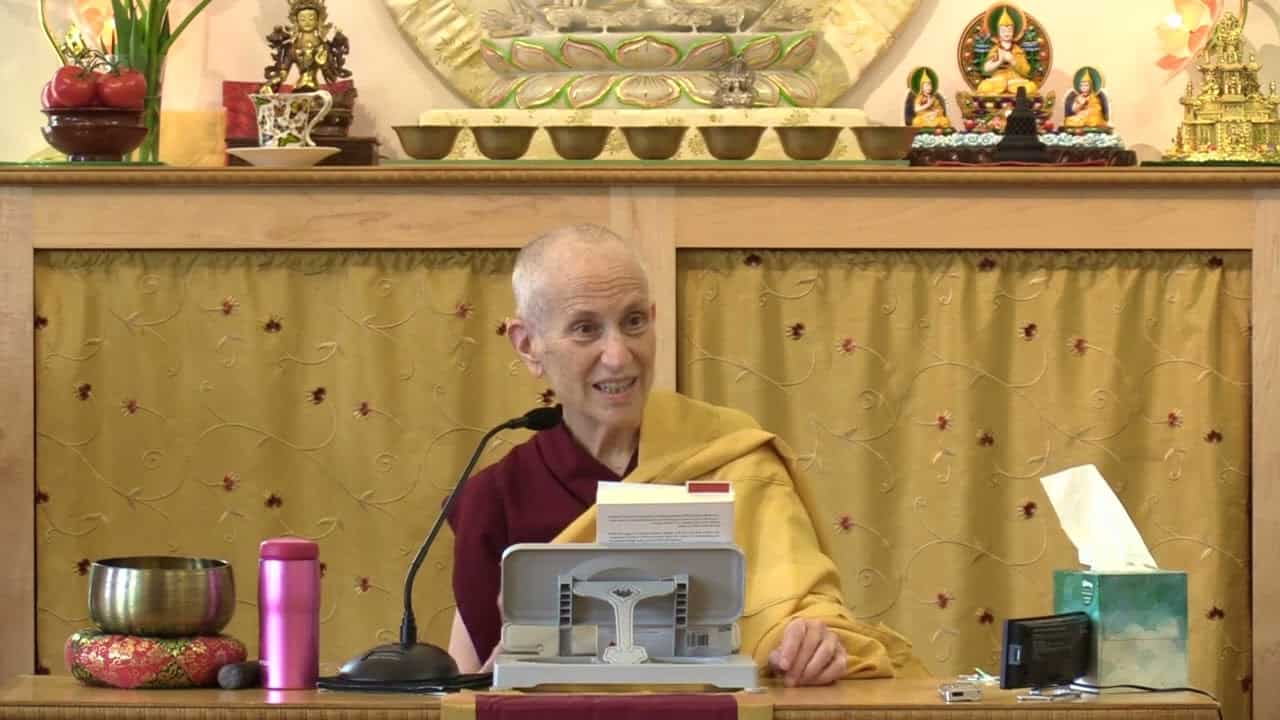

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.