Auxiliary bodhisattva ethical restraints 13-18

The text turns to training the mind on the stages of the path of advanced level practitioners. Part of a series of teachings on the Gomchen Lamrim by Gomchen Ngawang Drakpa. Visit Gomchen Lamrim Study Guide for a full list of contemplation points for the series.

- Discussion about distracting amusements and reducing attachment to them

- Correcting our own and others destructive behavior

- How to respond to insults, anger, abuse and criticism with fortitude

- Not neglecting those who are angry at you

Gomchen Lamrim 93: Auxiliary Bodhisattva Ethical Restraints 13-18 (download)

Motivation

To start with what is quite evident, which we and all other living beings, no matter who they are, whether they’re humans, mosquitoes, or whatever, all living beings simply want happiness and freedom from suffering. Our difficulty is that we don’t know what causes happiness and what causes misery, and we often shoot ourselves in the foot by doing things that we think will bring us happiness but because we are ignorant about how karma works and how our mind works, the things we do often lead us to unhappiness instead. So now we’ve encountered the Buddha Dharma we have a chance to learn it, to put it into practice, to really learn what causes happiness and what causes misery, to gain confidence in that, something more than just lip service, so that it really changes how we live our life, what we choose to do, and what we choose not to do.

While we’re learning and working on this let’s do it with a very broad and expansive mind, a mind that is open-minded to new ideas and a mind that can include within it the fact that other living beings are just as important as we are, because each of us calls ourselves “I”, and so each of us feels “I want to be happy. I don’t want to suffer. I want to be respected. I want to be secure.” Everybody feels that equally, so there’s no reason to cherish our own welfare over others. Let’s have a big mind that wants to eliminate misery no matter who’s it is, simply because it’s misery, and a mind that wants to create happiness no matter who’s it is, simply because it’s happiness. With that kind of attitude of compassion and altruism, let’s follow the path to full awakening so we can actually bring about the welfare of others without wasting a lot of time and energy, without tripping ourselves and others up. So, generate that altruistic intention for listening to the teachings and also for the whole weekend retreat.

13. Being distracted by and having a strong attachment to amusement or without any beneficial purpose leading others to join in distracting activities.

We finished number twelve, so we were in the middle of talking about the bodhisattva precepts that have to do with ethical conduct. The next one is a real doozy, and it reads,

Being distracted by and having a strong attachment to amusement or without any beneficial purpose leading others to join in distracting activities.

This is in the red prayer book, page 80, number thirteen. “Being distracted by and having strong attachment to amusement.” Anybody here have that? Just what kind of amusement? Well, the TV, the internet. The news is really amusing nowadays. We’ve found all sorts of things to amuse ourselves with. We look at catalogs, vacuum cleaner catalogs, seeds-for-your-garden catalogs. I fly a lot; people take out these magazines that you’re supposed to look at in the planes and all the things you can buy. They look at that and it’s so boring. We really like amusement. We want to go out singing, dancing, and Christmas-caroling, to parties, discos, and out having a lot of fun, maybe just out to dinner. All the things that we usually enjoy. Here it’s saying being distracted by them and having strong attachment to them.

Being distracted by…

What does that mean? It means that we have an opportunity with our precious human life to really learn the Dharma and focus on the Dharma, but we have a really hard time finding time to do it. Why? Because we’re distracted by things that are much more amusing than sitting down and having to study a Dharma text. Or, just even read a Dharma text. It’s much more entertaining to listen to the latest White House scandal. It’s quite entertaining nowadays, isn’t it? And much more entertaining to go play golf. Maybe you’ll run into Donnie on the golf course. We get distracted by all these other things, so we never get around to really studying the Dharma, putting it into practice.

So distracted by it and having strong attachment; it’s like “I really want to do this,” I really want to play this computer game. It’s so interesting, fascinating and they say it’ll prevent me from getting Alzheimer’s.” Isn’t that what they’re supposed to do, because it keeps you awake? How many little things you can shoot down? Playing solitaire by yourself. Playing solitaire with the computer. We are amused strongly and strongly attached to these things. And often Saturdays and Sundays – I am not saying people shouldn’t relax and enjoy. It’s fine to relax and enjoy, but we do go a little bit beyond that to just zoning out in front of the tube all weekend. Anybody do that? You watch football, then golf, then basketball, then, or maybe you watch…

Audience: Saturday Night Live.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Saturday Night Live, yes. That’s actually good – they make fun of the President. I think laughing is very important nowadays. Saturday Night Live. When I was little, it was the Lawrence Welk show on Saturday night. Anybody remember Lawrence Welk on Saturday night? And Ed Sullivan on Sunday night. You remember that? Never missed it. Now instead of that they have other things. Poor Lawrence Welk. Do you remember that? They all did the dancing.

So, we never get any Dharma practice done because we have our social engagements, we have our hobbies, we have our family dinners. My sister’s getting married on Sunday and I chose to be here with you instead of at the wedding. I am going to miss out on the party, the cocktails, and the dancing. They’re having a fun weekend; they’re going golfing and swimming and all sorts of stuff and I’m sitting here with you. Which I am much happier doing than going to a wedding reception, where you can’t even hear people talk because the music is so loud. As much as I love my sister, what I really want to see in the wedding probably takes about 45 seconds. I want to see her two kids walk her down the aisle. The rest of it… I hope she doesn’t watch this teaching! But for them it’s fun, for me it’s something else.

But I have my other things that I’m attached to doing. You give me a long walk in the forest, and I’ll go for it. We need exercise, that’s fine, we need some relaxing time, but this is talking about keeping ourselves as the busiest of the busy to the detriment of our spiritual practice. And the disadvantages of doing that is that having the opportunity that we have with our precious human life took us a long time, many lifetimes to create the karmic causes to happen, and yet this life doesn’t last very long. It comes and it goes and at the time of death we can’t say, “Hold on, I’m not ready. Can I have a few more years? I promise to turn off the TV and the internet, and stop going to parties, and doing some Dharma practice now. Give me a little bit more time.” Who are you going to bargain with? At the time of death who can we complain to? “It’s not fair?” Who can we bargain with? “Give me a little bit more time. It’s no sweat off your back.” We have nobody to bargain with. It’s just cause and effect.

So, if we’ve chosen to spend our time in distraction, we need to accept responsibility for probably dying in a lot of confusion and turmoil. If we don’t get so distracted, keep our mind focused on what’s important and do some serious practice, then dying can be very relaxing. They say even for the very great practitioners it’s like going on a picnic, they feel so happy.

It’s not anybody saying, “You’re not supposed to be distracted, this is bad.” Nobody’s saying that. It’s just up to us to choose how to spend our time being aware of what are the results of distraction and what are the results of study and practice of the Dharma. This has to do also with this,

Without any beneficial purpose leading others to join in distracting activities.

Like somebody wants to come to retreat and you talk them out of it. Or somebody wants to do their evening practice, but you say, “Oh, come on, let’s go do this and that instead.”

Bringing others to distraction and preventing them from practice. Many people see that as showing kindness to their loved ones, but that’s because they don’t understand karma and rebirth. If you understand that, then you realize that distracting your loved ones from the Dharma is harming them, it’s not being kind to them. We just waste a lot of time singing and dancing and laughing and being very excited. You know how it is sometimes when you get with your friends, and you just carry on and you’re laughing hysterically and everybody’s just being really silly. You all look so serious right now.

You’re doing all of that, so then it does something to our mind too. It makes our mind quite restless, and it makes our actions very careless, especially if we’re drinking and drugging when we’re together with our friends. It leads to a lot of carelessness. And it’s so funny, because we always say we read about what happens to people when they get drunk, in the newspaper, but we always think, “Oh, I would never do anything like that.” But the people who do those things and wind up either in trouble themselves or being victimized by somebody else didn’t think they would ever wind up in that kind of situation either. When you add alcohol and drugs to this kind of thing, our behavior really gets careless and all over the place. This is one of the precepts. This is a tough one to keep. It’s tough because we are attached to amusement and excitement and our social life and everything.

14. Believing and saying that followers of the Mahayana should remain in cyclic existence and not try to attain liberation from afflictions.

Then fourteen is,

Believing and saying that followers of the Mahayana should remain in cyclic existence and not try to attain liberation from afflictions.

This one is easier to keep without transgression. What this means is, somebody is looking at the Mahayana tradition, the bodhisattva vehicle in particular, and is saying that the people that follow this should remain in cyclic existence and should not try to attain liberation. The people who believe this have misunderstood the teachings. How they do that is because there are certain sutras that say that bodhisattvas take delight in being in samsara. A bodhisattva is somebody who has that spontaneous altruistic intention, wanting to become a Buddha for the benefit of all beings. When it says that those people take delight in samsara, it doesn’t mean the way we take delight in samsara. It’s not because they’re going out to parties and looking for a good reputation and a lot of money and going on cruises and so on and so forth. They delight in being born in the samsaric world in order to have contact with ordinary afflicted living beings like us, to be able to teach us and guide us on the path. They don’t like samsara because samsara is a lot of fun, because they’ve actually seen that samsara is a big hellhole.

So, when the scriptures say, “Oh, they don’t seek liberation because they enjoy samsara,” it means that they’re not seeking their own personal liberation, but they’re choosing to come back in this confused world for the benefit of the rest of us. Actually they want to attain liberation, they want to attain full awakening, but instead of attaining their own liberation, their own state of personal peace, of nirvana, they’ve chosen to stay in this world and accumulate merit by being of benefit to sentient beings so that they can attain the state of full awakening or Buddhahood which is a higher state than the state of liberation attained by arhats. They’re willing to spend [a] longer time accumulating merit in order to attain full awakening and it’s just that they do that here, they’re giving up their own bliss for the sake of attaining full awakening to be able to benefit us. So, we don’t believe or say that they should remain in samsara and not try and attain liberation from afflictions because their aim is to attain full awakening because then they’ll have all the wisdom, compassion, power, skillful means and so on necessary to benefit others.

15. Not abandoning destructive actions that cause you to have a bad reputation.

Number fifteen,

Not abandoning destructive actions that cause you to have a bad reputation.

Now you’re going to go, “but I thought you weren’t supposed to be attached to our reputation. Isn’t that one of the eight worldly concerns, being attached to our reputation? So why is there this one here about abandoning things that cause me to have a bad reputation?” Here first of all what we’re abandoning is destructive actions that we shouldn’t be doing anyway, even for our own sake. There’s no benefit to those actions and as a bodhisattva, for practicing the bodhisattva path we need to have a good reputation. But the reason for having it is very different from the reason we worldly beings want a good reputation. Because we want a good reputation, because it bolsters our lack of self-confidence, it masks our insecurity, we can get certain perks from it. Maybe people will give us presents, we’ll get high status, and we’ll get privilege. So, we want a good reputation simply for very self-centered reasons. Bodhisattvas want a good reputation because they realize that if they’re going to be of any benefit to others, other people are going to have to respect them. If they do destructive actions and they act any old way, ordinary people aren’t going to respect them, they aren’t going to want to learn from them, and then bodhisattvas will be unable to fulfill their aspiration which is to benefit sentient beings.

This is a situation, for example maybe we made a mistake, somebody criticizes us for that mistake and we’re having a bad reputation because of it, but we just say, “Well, who cares, I don’t care what they think of me. Whatever they think, blah, blah, blah.”

And that’s being quite irresponsible, we’re cutting off our ability to benefit that person because they won’t respect us. We’ve made a big mistake and we’re not owning it; we’re not being responsible for it. Why should they respect us and want to learn the Dharma from us? That’s ridiculous. So, if we made a mistake and people are criticizing us for it, we have a bad reputation, we should definitely apologize to those people and make amends and be responsible for our actions. That will at least show them that we have some integrity and some consideration for others.

On the other hand, sometimes people misinterpret things we say or do, and they get mad at us and criticize us for something that we didn’t do. Again, a transgression here is just saying, “Well, forget it. Those people are so stupid, they are accusing me of something I didn’t really do. Just forget it.”

Having that attitude too impedes our being able to benefit those people. If there was a misunderstanding and they’re criticizing us and they don’t have a good feeling for us because of this misunderstanding, we need to explain what we did and clear the air. It is important that we have good relationships with people and that they see us as somebody who is trustworthy, who has integrity, who assumes responsibility instead of just kind of shining things on. There may be certain situations where we feel that even if we tried to clear the air, the other person is not going to listen or maybe they’re just going to even get angrier. In those kinds of situations, it’s not a transgression to not go and talk and apologize and so on. But in general, we should try and keep things clear. So, we care about our reputation but not for self-centered reasons.

16. Not correcting your own afflictive actions or not helping others to correct theirs.

Number sixteen is

Not correcting your own afflictive actions or not helping others to correct theirs.

We may be doing all sorts of negative actions and again just saying, “Well, so what. I don’t care what other people think, I don’t care about my karma, I’m going to do what I want to do, it doesn’t really matter. And anyway, I do most of these things where other people don’t see me so who cares if I do negative actions or not?”

We definitely have that attitude, don’t we? “If I do it and nobody knows, then it’s really not so bad, it doesn’t ruin my reputation.”

But karma doesn’t care about reputation, we still accumulate the negative karma, so we need to correct our own afflictive actions. And here also, a transgression is not helping others to correct theirs.

Here’s a situation in which somebody is about to do a very serious destructive action: harm somebody else, self-sabotage, [or] really about to make a big mistake, and we don’t do anything to talk to them or to distract them, or to change the conditions so that they don’t do it because we’re afraid that if we say anything they’ll get mad at us. We have this problem, don’t we? We see people saying things that are not helpful, doing destructive actions, but we don’t want to say anything because they may get mad at us, and we don’t want people to be mad at us. There, avoiding people being mad at us and criticizing us is more important to us than caring about whether they create horrific negative karma. That’s pretty self-centered because we’re just like, “I don’t want anybody to scream at me, I don’t want anybody to think bad of me, I want to have a good reputation, I want everybody to like me, I’m not going to risk my reputation to interfere in this.”

Very self-centered. We’re afraid of offending them, we’re afraid they’ll get irritated, they won’t like us. But we have to see that if we really have compassion for somebody, sometimes it means saying things very clearly to them and they may get upset with us, but if we’re doing it with a good intention and it serves the purpose of preventing them from creating some serious destructive karma, then who cares whether they like us or don’t like us.

The previous one we were just not caring about our reputation and not fixing things up which is detrimental for others because they don’t want to hear teachings from us or whatever. This one is, we’re not brave enough to say something to them that will stop them from harming themselves or harming others because we just want to be people-pleasers and have everybody think we’re wonderful. I’ve talked about this many times in the community, that it’s so important that we help each other when we see somebody is going down a slippery slope. That we don’t just stand by and let them go down a slippery slope and create a lot of negative karma because we’re so attached to people liking us.

This involves a situation where somebody’s really doing something that’s not good. We’re not talking here about correcting tiny faults. We’re not talking here about becoming the world’s policeman or policewoman, picking at everybody over their tiny faults and correcting them, thinking that we’re doing very good. Because doing that is not coming from a compassionate attitude, that is our wanting to control other people. We have to discriminate [between] many different states of mind here and really see what our motivation is. If we’re picking at people, “You put your shoes this way. They’re supposed to be this way. You didn’t do this, and you should’ve done that,” just picking at people with a negative intention because you’re trying to make them be what you want them to be, that’s definitely something to abandon. Doing that is not the definition of keeping this precept.

You read about these frat parties; we’ve been reading so much in the news about these. The frat parties and the kids doing stupid things and people dying during “rushing” or to become a member of a fraternity or sorority. Hazing also, all this kind of stuff. In sports teams it happens. People do this kind of thing, and they think, “Oh this is really clever and let’s put everybody through the test.” We’ve been reading about young people dying in these situations and nobody being responsible. The one that’s been in the news recently, they made him drink some incredible amount of alcohol within a very short time. His blood alcohol was I don’t know how many times greater; I mean some incredible – four times or eight times greater than what it is to be drunk. The guy fell down the stairs, injured himself, the other kids put him on a sofa. Gee, that’s really nice. But he’s bleeding, he’s unconscious, and he died the next morning, still drunk. And now these kids at the frat party are facing charges for involuntary manslaughter, neglect, and things like that.

This is the kind of situation; I’m not talking about picky stuff. When somebody’s really doing something that’s not smart, it’s very damaging but you don’t want to say anything because all your other friends are going to think that you’re weird. If you say, “Hey, we shouldn’t be giving people so much alcohol to drink in a short time.” Or if you say, “You know, we should really take him to the ER room.” But you don’t say anything, because you’re afraid your friends are going to think you’re prudish and weird, and like that. That’s what we’re talking about here.

That’s a big example and all of us are beyond doing that because we’re no longer teenagers, so we’re thinking we don’t have that problem, of course we’d take somebody to the ER. But we find all sorts of other ways to not intervene if somebody’s doing something quite harmful. We may have a relative who has a drug/alcohol problem. We don’t say anything, [so] we become enablers because they’ll get mad at us if we point out to them that they have a problem. Our friends are about to do a really bad business deal, we don’t say anything to them. The legality of it is iffy or whatever it is. We don’t say anything, because they might get mad at us. These kinds of things.

Again, it doesn’t mean we go around correcting everybody over every tiny thing, but we speak up when things need to be spoken up about. In a monastic situation we do this, this is the whole thing about giving each other advice, and how important it is in a community to advise each other when we see somebody going down a slippery slope. We do it when they’re still at the top of the slope. We don’t wait until they’re two-thirds of the way and they’re about to crash at the bottom. That’s not very compassionate. This particular precept is contrary to the ethical conduct of helping others because we are letting them make serious mistakes.

Number eight to sixteen, those nine precepts are for ethical conduct, helping us to keep good ethical conduct. It’s very interesting as we go through many of the other ones to come. Many of them relate back to the three kinds of ethical conduct of not restraining harmful actions, doing virtuous actions and of benefiting sentient beings. Many of the precepts actually pertain to more than one of the six perfections.

Now we’re going to eliminate obstacles to the perfection of Fortitude. There’s only four here so we think, “Only four things having to do with anger, I can make it through this one. Maybe my anger’s not so bad.”

17. Returning insults with insults, returning anger with anger, and returning criticism with criticism.

Let’s start with number seventeen, which is the first one.

Returning insults with insults, returning anger with anger, returning criticism with criticizing them.

Somebody beats us up, we beat them up. Sounds very human. Isn’t that what most of us do? Somebody insults us, somebody verbally abuses us. Do we put our hands together and say, “Thank you so much. You just helped me use up some negative karma. Thank you so much. You’re giving me the opportunity to practice patience.”

We don’t do that when somebody insults us and abuses us! We throw a fit and we yell back at them and let them know in no uncertain terms that there’s no way that they can speak to us this way. We insult them back; we verbally abuse them back and we throw it all back in their face. It’s called getting defensive but other people call it sticking up for yourself. And we’re often taught as children this is what you should do. Somebody calls you a name, you call them a name back. Really useful, isn’t it? That’s what is going on at the highest level of government, what people are doing. They’re just calling each other names. Nobody’s trying to make good policies or do anything for the people. They’re just calling each other names. But we’re not like that. We’re civil, we’re better than those politicians. But we do. Somebody insults us, we insult them back.

The practice of fortitude here is not returning insults with more insults. Now the question is going to come, “How in the world do you do that?”

To avoid doing that you have to not be so reactive when other people insult you. You have to be able to hold your center and realize when other people insult you that they’re basically saying more about themselves than they are about you. And to hold our center. I was thinking of when Jan Willis was here last weekend, and she was telling us a situation. What was it? Where she got very offended, it had to do with race. She was going to visit her parents. No, her friend’s parents, that she already knew, and they kind of expressed some shock that, “Oh, you’re black, and you’re coming into our home,” even though she knew the family. She came to understand later, it’s because there were some troubles between the blacks and the Jews in that community at that time. But still she was very hurt, she was very offended by that, and most people would be.

When she told that story it made me remember a situation when I was in seventh grade. I was raised Jewish in the shadow of the holocaust. “You’ve got to be careful.” And, “They just killed six million of us.”

And so on. It was a Monday morning I think, and it was Current Events class. One boy in my seventh-grade class, Peter Armeda, who I’m waiting to meet some day, said something to the effect of, “Why don’t all you Jews leave the country and go back where you came from?”

I was twelve, I just took this to heart, I ran out of the seventh-grade class, the poor [teacher] didn’t know what happened to me. I went into the girls’ bathroom, cried all day. I refused to go back into my seventh-grade classroom, I was so hurt, so offended, so insulted. And I realized years later that I had been taught that when people made anti-Semitic remarks, I was supposed to be angry and I was supposed to be insulted and enraged, that you learn these kinds of things.

After I met the Dharma, I began to see that at that time you actually have a choice. You can choose to be offended, or you can choose not to be offended. For some people the reaction of being offended is so instantaneous and it lasts for years and years and years. Nowadays everybody is almost a member of some kind of minority or another, and we all have reasons to feel insulted and offended. I’m not saying those reasons are invalid, what I’m saying is that we do have a choice. And if you choose not to be offended and not to reply to insults with insults, it doesn’t mean that you just let somebody go on talking in a bigoted way. We shouldn’t think that having fortitude means that you become the doormat. You can be completely calm and not feel offended but know that this is a time where you need to educate somebody, and you need to give somebody some feedback so that they understand the effect of their speech on other people.

Are you getting what I’m saying? That instead of responding like I did, crying in the bathroom all day or instead of crying in the bathroom all day, that was something ok for girls to do, if I had been a boy I probably would have yelled and screamed and gone over and punched him, because that’s what you’re supposed to do when you’re a boy. But to realize how this is conditioned behavior and there is a choice in there. When she told that story it made me recognize that situation where I was insulted for being Jewish.

Then it made me remember another situation where I was insulted for not being Jewish. The second situation happened many years ago, I can’t remember. I was teaching in Israel and one of my friends, part of her family, lived in the West Bank. They were part of the settlers who lived in the West Bank, and they invited us over to dinner. They invited my friend, and she said, “I want to bring some friends with me,” and they said, “Sure! ” So, we got there and then, I think she may have told them beforehand that I was raised Jewish, and it’s not just “raised Jewish” – you are Jewish. When you’re Jewish, this thing that we say on Passover, “Let my people go,” it’s not just talking to the Pharaoh, the Jewish community will not let you go. So, I was going to this Shabbat meal, and I was a Buddhist, but I was in their eyes really Jewish and a traitor because I was not remaining Jewish, and I had another religion. When we came in and my friend was introducing me to her aunt and uncle, they did not look at me, they did not shake my hand, they did not say “hello” the entire evening. That was a very interesting experience.

There again, I could have chosen to be very offended because the way they were acting was anything but hospitable or open or anything like that. But at that time, I knew, you know how people think. And you realize that’s just how they think, nothing you say is going to make any difference. “Forget it, just enjoy being there. It doesn’t matter! I know the culture. There’s no reason for me to get upset, this is what they do.” So that’s what I did. My friend of course was very apologetic on behalf of her relatives.

Later on, I think the same trip, or another trip, there was one young woman who had been in a car accident or something. She was unconscious and at a hospital, so her friends asked me to go and do some prayers and so on. I don’t know if she may have been to one Buddhist course or something, she definitely wasn’t Buddhist, she was from a Jewish family, and her uncle from New York. If you know anything about New York Jews going to Israel, they are the most conservative of the conservative. These are the ones who move into the West Bank for ideological reasons. It’s not like the Russian Jews, who live in the West Bank because they’re poor and they can get housing there. These people deliberately move there because it’s their land, and they’re going to claim it. Her uncle from New York was there and I went and did some prayers and things like that and as I was leaving, her uncle said,” Don’t forget you’re always Jewish.”

So, again I could have been really offended, and said, “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Who do you think you are? You’re so bigoted against people of other religions, nyah, nyah, nyah.” What’s the use? I wasn’t really offended. I know how people think.

In both these cases I didn’t say anything to the people, because I knew it wouldn’t have done any good. Now, going back to Peter Armeda in seventh grade, if I had been on top of the situation then, I could have done a very nice NVC statement, that would have let Peter know that this kind of speech is uncalled for and it’s painful, and so on. And I could have said that even if I personally wasn’t offended, but to let him know that other people would certainly be hurt by that. But of course, I was too busy crying in the bathroom to do that.

I got off on a little tangent here, but I hope these examples kind of show how to deal with some of these things or at least how to try and apply some Dharma to real life situations. I won’t even tell you the stories about facing discrimination because I’m a woman in the Tibetan community. I won’t even go into that. I’m sure many women here, everybody has stories of some kind or another where people were just out and out prejudiced against us. That’s one example here of being insulted or it could be somebody on a personal level who’s insulting you, not because they’re bigoted but because they’re mad at you for one reason or another. Because sometimes we make mistakes.

If somebody’s mad at us we usually get mad at them back, and our anger is justified. Even if we withdraw and don’t speak, we were hurt, (especially if you’ve been socialized not to express anger but instead to cry), and even if you cry, you’re angry. You’re angry so we’re still replying to anger with anger. Somebody beats us, we punch him back. Very good for the hospitals! They make a lot of money on us retaliating. I mean, you think, what is the murder rate in Chicago now? There’s been all sorts of articles about that, way up, horrible murder rate, just shootings in general. Why? Retaliation. Somebody does something you don’t like? You shoot him back or you beat him, or you stab him or do something. How many people die because of this? Too many. This also goes into national policy, doesn’t it? What did the French do after the thing in Paris? They sent their jets to go bomb in Syria.

And then, we,

Respond to criticism with criticism.

And that’s what we do when we fight people, especially the people we care the most about. Most of our fights, aren’t they just one person criticizing the other and the other criticizing that one back? Isn’t that what most marital fights are about? Or fights with your good friends or fights with your kids. “You’re so…fill in the blank.”

And they say, “But you’re so… fill in the blank.”

You could write a whole script for it and then just fill in the blank as you wish. This is what we do. “You’re so da da da da da, because you did da da da da da. Which means you don’t care anything about me, di di di di di.”

“Well, you did da da da da da, and that means duh duh duh duh duh, and you don’t care about me either.”

So, it’s the pot calling the kettle black.

What about number thirteen,

Being distracted by and having a strong attachment to amusement

Some people like fighting. Have you met people like that, who love to fight? I worked – tried to work – with somebody who loved to fight. I didn’t know this about them when I first started working with them. They seemed like a really nice person, and there were a few little red flags, but I ignored them. And then I realized that this person loved to fight. That’s just how he got clarity on his ideas, how he got a feeling of communication with somebody. He just loved it, I didn’t. I’m not a yeller and screamer. He would go on attack mode, and I remember one time I just stood up and walked away. Oh boy! He was so furious when I walked away.

So number seventeen is about how we respond to these difficult kinds of situations. And we usually respond in kind, and how does the situation usually end? Badly, with people saying all sorts of horrible things to the people they care about the most. People harming each other physically so that everybody suffers afterwards. Often when I go into prisons and the guys have asked me to give a talk, I give a talk and I’ll say, “How many of you are here because of anger?”

Every hand or almost every hand goes up. “How many of you are here because of anger?” Does anger really help you? Gives you a sense of power but does it really help? That was number seventeen. Anybody have anything they want to add to this one?

Audience: Even if I’m not responding to someone, having malicious intent towards them, going-off and ruminating about what they did in my head and why they’re bad, just wastes vast amounts of time and energy.

VTC: It’s true. We can waste a lot of time and energy because we ruminate, and we run through the situation again and again. Inside of us we have a judge, a jury and a prosecutor. And we re-run the situation, prosecuting that other person in our mind for whatever thing they did. The jury in us convicts them and the judge gives them a death sentence or something appropriately severe enough, “You are now worthy of my eternal hatred.”

We spend hours, don’t we? Anybody here like to ruminate about what somebody did to you that wasn’t fair, and it wasn’t right? They should know better, and they shouldn’t treat us that way anyway…. A lot of time.

Audience: Venerable, I have a question. It’s not related to number seventeen, but more on your stories about Jews. How do you handle some kind of situation where you are neither here nor there. Like you said about Jews, people call you immigrants but on the other hand the Jewish community itself does not really accept you because you are a Buddhist, but you are also not Tibetan. Aren’t you like, confused, like [in] identity crisis? I’m neither here nor there.

VTC: You are saying, “Doesn’t this kind of bring on an identity crisis?”

It’s like the Tibetans don’t accept me because I’m a westerner and the westerners don’t accept me because I’m a Tibetan nun and the Jews don’t accept me because I’m Buddhist and the Buddhists don’t accept me because I grew up Jewish. So, don’t I get confused about who I am? No. No. I feel very happy having a rather fluid identity like that. I’ve spent a good part of my adult life living in other countries and I really cherish that because I don’t think like a particular nationality. I’ve taken some things from all the different cultures that I’ve lived in and adopted that into the way I think or the way I act. I feel quite comfortable with that, like I got to pick the best thing from everybody.

Audience: I’d like to share a story kind of related to that, and also to precepts number sixteen and seventeen. Last year we were in east Malaysia where the Chinese are a minority, and the Muslims are a majority. Malay Muslims are a majority in Malaysia. We were at this lunch where someone, a Chinese Buddhist, started to say things about the Muslim community. About his fear as a minority coming out as racial hatred. At that moment I got paralyzed. I know the culture. I know the fear. I feel ashamed of racism coming from other Chinese people. I feel guilt that I’m supposed to identify with being Chinese, like all this identity stuff happening. I was like, “I don’t want to. I don’t believe anything he says.”

And all Venerable did to break that silence was just to say, “I’m really uncomfortable when you talk about groups of people as if they are all one thing. And, especially groups of people, if those people are not represented here.”

I remember you speaking up like that and it just shifted the whole conversation. I felt so relieved that you spoke up to indicate the effect of someone speaking like that. Whereas I think maybe everyone at the table, because everyone was Chinese, maybe would have not said anything.

Audience: Venerable, a few years ago when you taught these, it wasn’t striking me in this way at all. Now, looking at sixteen, and in the political climate that we’re living in, it is seemingly to push us to not be silent and to step up and help correct others when they’re making mistakes. There’s a lot of mistakes being made all over the place, so this is really like, “Okay, we have to do it.”

VTC: We have to speak up.

Audience: Sixteen and seventeen, for me, really stimulate my admiration for Marshall Rosenberg. Using “empathy ears” to myself, and to the other person, as opposed to “critical ears” to the other person, or “critical ears” to myself. So, I agree, I feel like sixteen and seventeen are almost like bookends, like are you going to just be passive and hope people like you because you don’t speak up or are you going to be violent in your speech? Well, no, you don’t have to do either one of those. There’s this other dimension of care.

VTC: Yes. There are other ways to respond. Let’s do another one.

18. Neglecting those who are angry with you by not trying to pacify their anger.

Number eighteen,

Neglecting those who are angry with you by not trying to pacify their anger.

This is a situation where somebody is angry at us. Maybe we made a mistake. Maybe they misinterpreted something, and we don’t try to calm them down. We don’t apologize, we don’t explain our behavior, we don’t communicate in some way to try and help them release their anger. Maybe we’re proud, “This person is mad at me, and okay, I said something that wasn’t so nice, but I don’t have to go to them and apologize. They’re the ones who are so angry and insulting me right now. They’re the ones who need to apologize to me. What I said was just one small thing.”

Having that kind of attitude, “I don’t care if they’re mad at me, I don’t care if they’re suffering, I don’t need to apologize, I don’t need to explain myself.”

So, we don’t do this because we’re arrogant, because we’re still angry at them. Here, the object is a person who is mad at us, and we just say, “Forget them.”

Why is this harmful? Well, our behavior is just furthering the conflict. We’re not being responsible; we’re not communicating so we’re just maintaining the conflict with the other person.

Audience: What if they’re just angry at you for who you are?

VTC: You mean like a situation of prejudice.

Audience: Like I’m a woman.

VTC: If it’s something like that you have to see what the situation is and see. Sometimes there’s nothing I can say. So it’s best to be quiet. Other times, you could say things, and here’s where NVC could be very helpful. If somebody is just angry at you and insulting you because you’re a woman to just say, “I feel – whatever you feel – I feel hurt, or I feel offended, because I would like good communication, and I would like mutual respect in my relationships with other people.”

Talk to them and just see what they say. If you talk about what they’re doing and point fingers you’re going to get a defensive reaction. But if you just talk about how you feel, it is very surprising for the other person, I think. They’re rather surprised.

This is number eighteen. There are some exceptions here, five of them. One is,

For good purpose.

If for some reason, it’s better for the other person to be ignored because in the long run it allows them to reinforce their good qualities or weaken their faults you can just ignore them. They’re mad at you, you just ignore them, let them be. But then there are also some other exceptions here.

One is,

The angry person himself is malicious, ill-behaved, has bad intentions, and wants to make us apologize to him.

If it’s that kind of situation, somebody’s mad at you, they’re trying to manipulate you into apologizing and they really have a bad intention towards you, then it isn’t a transgression if you neglect to try and pacify their anger. Remember this is somebody who for whatever reason, is mad at us.

Another exception is,

If apologizing would aggravate the situation by irritating the person further.

Perhaps leading to a fight. You know how some people are? They’re like, so mad that whatever you say to them, they just get angrier. Those situations, better just let them cool, let them chill out. This is how I learned to deal with some family members when they get mad at me. I just completely… Because if I try and say something, it’s like, “Who do you think you are to say something nah nah nah nah nah?”

So, I ignore it.

Another exception is,

The person is naturally patient and would be indifferent to our apology.

You come across somebody who is mad at you but they’re naturally patient, they don’t need an apology; that’s a rare person. Or maybe somebody who would feel uncomfortable if we apologized, in that situation we don’t apologize. Or, if our apologies would embarrass somebody else, it’s fine to not apologize.

Audience: I just had something, a thing that happened, where I learned a lesson by applying the Dharma. It was at work; I was working on a project. My boss had given me what I thought was the responsibility for the project. But I was working with another woman who thought she had the responsibility, I don’t know what was said, whatever. But I left her out of some of the communication and she was very offended by that. I did not realize it at the time, but she let me know and I was so upset, because I would never have wanted to do that, didn’t mean to hurt her, all this kind of stuff. I went home and just thinking about it I’d get that feeling again. So, I did apply some of this and I thought, “Well, I need to communicate with her.”

And I was so scared to do that. Here’s this woman, she just went off on me yesterday and I’m going to go and put myself in the line of fire again. But I thought, “I need to do that. I need to at least communicate and share my side of the story.”

And I felt better. I don’t know about her. She listened to me, and we have [a] better relationship, I think, now. But I felt better about the situation at least.

VTC: And it’s sometimes brave to go and talk to somebody who you know is mad at you. But if you go with the intention to try and settle the situation, it sounds like at least this person was able to listen and take something in.

Audience: In my working life, I’ve worked about twenty years in customer service, and so, it’s like, “Yes! I’ve done this a lot!”

Because you have no idea what the situation is and you have people coming up to you just frothing with anger. I have some training for doing this, and one of the first things they say is, “Don’t explain what’s happened. They don’t care what happened. They’ve got a problem. They want you to fix it.”

So, one of the things that I’ve taken to doing is that the minute they come up to me and the energy is just like a wall, is to just say, “Thank you.”

Which completely throws them off for a second. Cools them down, most of the time, just like that. To just say, “Okay, thank you.” And then see what you can do about the issue.

VTC: Yes, or especially offering them some empathy. “Boy, you’re really angry, because you got this and you expected it to work, and it doesn’t.”

And they go, “Yes!” Then they know you understand. That’s what they want. Somebody who is going to understand and listen and help them.

Audience: Sometimes they just want someone to hear them, particularly older men, has been my experience. In our society as they’re getting older, our older men are just not listened to or heard or at least this is their feeling. So, if you take the time and just listen to them sometimes, you’re like their best friend then.

VTC: Customer service is a hard job but what an opportunity to practice!

Audience: I have found what you said here, that many times the angry reaction says a lot more about the person who’s angry than you, and I think part of what gets me into so much trouble is that any time there’s a very strong reaction, no matter how hard I try to be clear, at least make an effort, there’s so much personalizing. There’s so much about “I”. There’s so much about self. So, it has been helpful to say, “This is not mine.” I can be open to hearing, and also to turn it back and say, my anger is not about them either.

So, taking responsibility for my own anger but not jumping the gun and trying to take responsibility for somebody else’s strong feelings as well. And when I see it within the context that this is about an afflicted mind right now that’s suffering, whether it’s mine or theirs, it sort of drops the whole thing down into a space of connection because I can understand. Also, it just softens the whole part of my mind that would be wanting to “fight or flight”. It’s really helpful to know that afflictive states are not mine, and generally not personal. Or if they are personal, it’s my suffering mind. It’s not somebody else causing my suffering mind.

VTC: But it is quite amazing how we take things personally. We just instantly [go to] defense.

Audience: Now we know what we should do, what practice do we do to gradually move closer to being able to do that?

VTC: Well, you listen to the teachings about anger and how to practice fortitude. As we’ve been talking here, we’ve talked about many antidotes here. You go home and you meditate on them, take out situations in which you have gotten angry, and you contemplate those situations seeing them from a new perspective. For example, Venerable Semkye was saying, “Somebody’s criticizing me but it’s not personal. I don’t have to take this personally, it’s somebody else feeling distress.”

So, you re-run a situation you had in the past but now you’re thinking in a different way. You practice that way of calming yourself, or any of the others. We’ve talked of many different kinds of things to say or do, or how to think, and you just go back through your own life experience in your meditation and imagine being in those situations, but with a different attitude. You just practice it in your meditation again and again and again and again. Doing it helps you clear up a lot of things from the past.

Audience: Can you say more about liking a fight. What is behind this?

VTC: What is behind it? I don’t know. What ideas do you have, because I’m not somebody who likes to fight. Who likes to fight? Who here likes to fight? So, what do you think is lying behind it?

Audience: Anger, wanting the situation to change, and frustration.

VTC: Frustration and wanting to make the other person change so the situation changes.

Audience: Maybe not the other person but wanting to change something about the situation. Frustration, and just things not happening as you would like.

VTC: Things not going the way I would like them to go and feeling angry and frustrated about that.

Audience: And, not having the words to be able to articulate what is it that you need, causes wanting to fight, because you see a problem, you want to be able to solve it but you don’t have the words for it.

VTC: That’s good. Something’s bothering you or you have a need, or you have something, but you don’t have the words to describe what’s going on inside of you. You just have the raw anger and frustration, so that comes out as wanting to have a fight, because it’s an attempt to communicate “I’m unhappy”. It’s an attempt to say, “I’m unhappy and I need some help. Or I need something, but I don’t even know what it is I need.”

And that’s what we’re really trying to say but it comes across as somebody else is yelling and screaming and blaming us and we have no idea what’s going on. Does that make some sense? Does that answer your question a bit? The person’s trying to say something, but they don’t have the words to express what they’re trying to say.

Audience: But I actually know another response to this. The first time my to-be husband met my father, we were visiting, and we’d go away, and he said, “Wow, your Dad really likes to rile you up.”

And I realized, my father always would start fights with me arguing about things. When I would be winning the argument, having the logic on my side, he would switch to my position, and it would just drive me absolutely batty. And when my husband said that to me, it suddenly occurred to me that what my father wanted was attention. After that whenever he’d start, and he knew things that I didn’t like, he would use the n-word, he knew that would always get me to pay attention. So, rather than respond to what he was saying, I would ask him about his day. I would talk about whatever project he was working on in the yard, whatever, whatever. And it was just this thing, “Well, he needs attention.” And me and my husband would just tag-team him with this overwhelming attention and [be interested in] what was going on for him. And it was great.

VTC: Well, this kind of fits in with what she was saying because he wanted something, he needed something, but he didn’t know how to say it so he picked a fight because that would get a reaction.

Audience: A kind of response to the question, “Does anyone like to fight?” Well, I was kind of like that, especially verbally, because growing up, we had this thing called “playing the dozen.” Basically, you don’t know what that means, it’s sort of like one-upmanship. We would talk about each other, and we would go from there, “Well, you know your momma this, your momma that.”

So, I think this sort of game was kind of this thing of power. Like, who could be the most skillful with their tongue, so cutting as much as you could. So, sarcasm was great, it was my friend and the more I could be sarcastic the better. But also, I liked to egg people on, like get people going. As I’m thinking about it now, I always thought those were good qualities. And, as you talked about how things are learned, that was just something that we did. That kind of thing. I thought it was good but now I know it’s not.

VTC: But it’s true. Very often with our friends, we get one-upmanship, and who can insult the other person more, the most.

Audience: I was in a relationship once where I learned that my partner at the time would never end an argument until she got me angry. I figured out that it was because she was wanting me to feel the same things that she was feeling. And a kind of a pattern developed around that. I was calm. I don’t know if it was like I didn’t care, or if it was some kind of need, emotional needs or something? I think that’s another piece of it, tracks with these other pieces, it is something that I experienced around getting into fights.

VTC: The person-wanting. Maybe that’s how they felt that you understood them. If you got angry just like they were angry. We human beings are so strange, aren’t we?

Audience: My father used to like to rile people up and it was just amusement for him. He was a truck driver, he had a CB, and he would say things on the radio. Other truck drivers didn’t realize it was another trucker. He was just amused by it. He would say things to people when they came to visit. “Oh, I’ll start talking to this person about nuclear power. Not that I care about nuclear power, but I know it’s going to rile them up.”

I don’t know, but I think some people do it for the boosting of the “I”. A big part of it.

VTC: And there’s a feeling of power, “I have the power to make somebody upset.”

Audience: I’ve been contemplating the social situation at large and seeing a lot of this playing out. Both sides are feeling alienated and powerless and it’s expressing itself as a national fight. And not just politically, our entertainment is reality TV, where it’s artificially set up as conflict. Or talk radio, it’s like we have no way to positively do anything and so we fight.

VTC: We’ve lost the ability to have civil discourse and to listen to each other. Sad.

Contemplation points

Venerable Chodron continued the commentary on the bodhisattva ethical code. Consider them one by one, in light of the commentary given. For each, consider the following.

- In what situations have you seen yourself act this way in the past or under what conditions might it be easy to act this way in the future (it might help to consider how you’ve seen this negativity in the world)? Consider some of the examples Venerable Chodron shared.

- From which of the ten non-virtues is the precept helping you to restrain?

- What are some of the exceptions to the precept and why?

- Which of the six perfections is the precept eliminating obstacles to and how?

- What are the antidotes that can be applied when you are tempted to act contrary to the precept?

- Why is this precept so important to the bodhisattva path? How does breaking it harm yourself and others? How does keeping it benefit yourself and others?

- Resolve to be mindful of the precept in your daily life.

Precepts covered this week:

To eliminate obstacles to the far-reaching practice of ethical conduct, abandon:

- Auxiliary Precept #13: Being distracted by and having a strong attachment to amusement, or without any beneficial purpose leading others to join in distracting activities.

- Auxiliary Precept #14: Believing and saying that followers of the Mahayana should remain in cyclic existence and not try to attain liberation from afflictions

- Auxiliary Precept #15: Not abandoning destructive actions which cause you to have a bad reputation.

- Auxiliary Precept #16: Not correcting your own deluded actions or not helping others to correct theirs.

To eliminate obstacles to the far-reaching practice of fortitude, abandon:

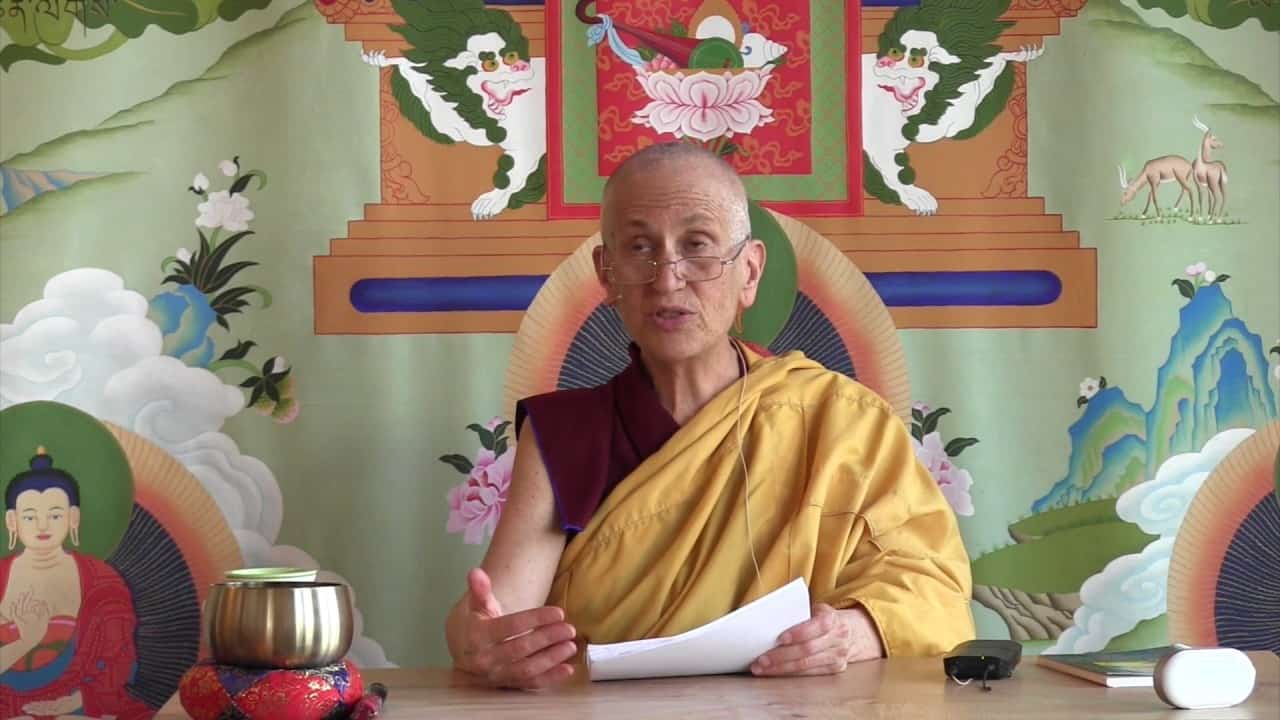

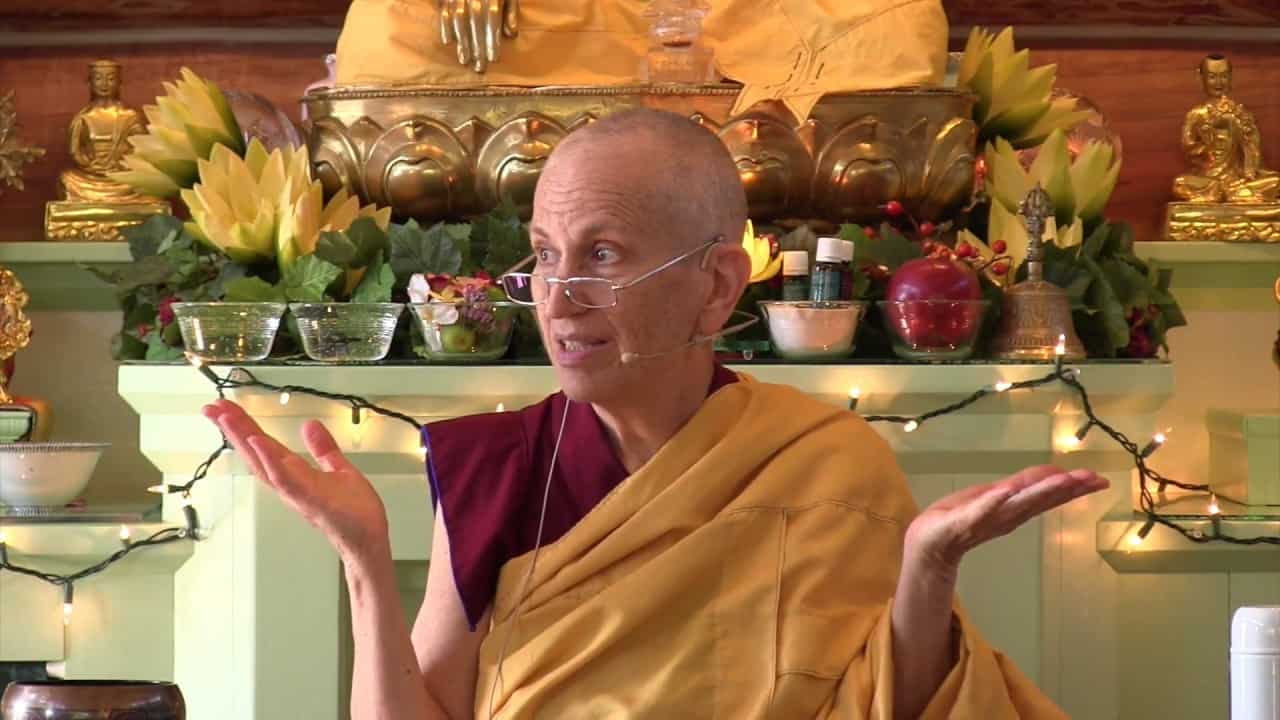

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.