Aspiring bodhicitta

The text turns to training the mind on the stages of the path of advanced level practitioners. Part of a series of teachings on the Gomchen Lamrim by Gomchen Ngawang Drakpa. Visit Gomchen Lamrim Study Guide for a full list of contemplation points for the series.

- Understanding the functioning of karma from life to life

- How to think when using something that has already been mentally given to others

- Two ways to perform the ceremony for generating bodhicitta

- Eight precepts of aspiring bodhicitta

Gomchen Lamrim 82: Aspiring bodhicitta (download)

Motivation

Let’s start with our motivation. When we look at ourselves in the mirror it seems like there’s a person in the mirror, and we generate all sorts of opinions about that person in the mirror. They’re too fat, too thin, they look old, they look young. Their hair is too straight, their hair is too curly. “Is this me? It doesn’t look like me.” We have lots of opinions about that person in the mirror.

And yet there’s no person in the mirror. There’s the reflection of a person, but there’s no person in the mirror. So, that appearance of the person is false, and yet it still functions because we generate a whole lot of opinions about it—not about the reflection, but about the person, even though there’s no person there. It’s just an appearance of a person, a false appearance, because it appears as a real person, but it’s not.

In the same way, every time we think about ourselves, whether we’re looking in the mirror or not, we’re generating a whole lot of opinions about ourselves. But the self that we’re generating the opinions about—some concrete, self-enclosed self that just “is”—that kind of self does not exist. There’s an appearance of that kind of self, of an inherently existent self, and the appearance functions, but there’s no inherently existent self there. And yet, we certainly have a lot of opinions about ourselves: who we are, how people should treat us, what we’re capable of, and what we’re not capable of.

That self that we have all those opinions about actually doesn’t exist in the way that it appears to us. But when we hear that, we just think, “Oh, it’s a false appearance, but it still really exists exactly the way it appears to me.” Every time we say, “Oh, it exists conventionally,” we go right back to inherent existence.

We have to somehow get it, how that person that appears so vividly to us—that self-enclosed, real person that doesn’t seem to depend on causes and conditions or anything else—that person doesn’t exist at all. When we hear that our mind screams out, “You’re wrong! That’s nihilism! You’re saying there’s no ‘I’!” No, that’s not what we’re saying.

There’s an ‘I,’ but not that one. But that thing is not the ‘I’ that exists. The more we can understand this, the more we can apply it in our daily life, then the more spacious our mind becomes because all those hurt feelings, all those insecurities, all that stuff is all about that ‘I’ that sets itself up, that exists from its own side. It doesn’t really exist at all. If we can drop the wrong way of apprehending or the wrong way of grasping the ‘I’, all that stuff we’ve put on top of it also crumbles and there’s a lot of space. We long for space but when we get it, it’s a bit unnerving.

We then generate a whole bunch more ideas and opinions to fill up that space so that we feel like we’re a real person again. It’s strange, isn’t it? We’re uncomfortable when we fill up the space, but we’re also uncomfortable when there’s space. We have to get used to the space, to chill out a bit, and then we can really use that space in a very productive way. So, with the motivation that wants to benefit all sentient beings, let’s see what we can do to understand that space, to perceive that space, to dwell in that space.

Did your mind scream nihilism? “What! That’s the conventionally existent ‘I’; you’re saying it doesn’t exist!”

A question about karma

Audience: If we commit a negative action against somebody, then in the next life, is it that person who does the same thing back to us? Until now, I’ve always thought no, not necessarily. I could criticize one person and that creates the karma for me to be criticized, but the criticism doesn’t have to happen from that person. But then I read something from Geshe Sopa’s Steps on the Path to Enlightenment where Geshe-la says:

But sometimes it seems as though someone is trying to harm you, even though you have done nothing to that particular person. In fact, you had done some action in the prior life that harmed that person. If the cause was not created at some point in the past the result [will] not occur. One person’s action leads the other person to act, the bad actions go back and forth gaining intensity. Karma created in prior lives causes a chain reaction, leading this person to react to you in this life [with a] spontaneous natural dislike and a desire to cause you harm. In either case, whether or not we know why the others are harming us, it is not right to blame them.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): I think what Geshe-la is talking about here is something that sometimes occurs, not all the time. And it doesn’t mean that just because we harm somebody then that same person is going to harm us back. If that were so, then neither of us could get enlightened until the other one had gotten enlightened because we would be obligated to stay in samsara in order to return the harm, which is ridiculous.

I think what Geshe-la was talking about is something that happens from time to time. And it happens on our part, too. It’s not just somebody spontaneously disliking us, but it’s also when, for no reason at all, we just don’t like the look of the person, or we don’t like the vibe of the person or something like that. There’s some kind of superstitious blah blah. And that would come perhaps from something in a previous life. Maybe they harmed us, so we have a funny feeling about them in this life. Or the same thing from their side: maybe we harmed them, and they have a funny feeling about us in this life.

But this doesn’t account for all the times that we receive harm because I think actually, a lot of the times when we perceive harm, there isn’t harm. At least when I look at the times when I get angry and I think somebody’s harming me, most of the time they’re trying to help me. They’re just not helping me the way I want them to help me. They aren’t really trying to harm me most of the time. Sometimes they might be, but most of the time they’re trying to help, and I just am irritated because “You’re not helping me the way I want to be helped!” It’s as if you’re supposed to be a mind reader and do everything the way I want. That would be nice. Yes, try it, but don’t read my mind when I don’t want you to read it!

Then there’s also a passage from Kensur Jampa Tegchok in Transforming Adversity, where he says:

There’s a particular way of meditating with respect to those beings who are full of hatred towards us and who harm us. Here we think specifically of all the violent vindictive beings in all the worlds of the ten directions, who have malicious and hateful minds.

Now, I don’t think that all of the violent, vindictive beings in all of the worlds have it out for us,

They may be unruly spirits and interfering forces, those to whom we are in debt from distant past lives and who are awaiting repayment.

Maybe we borrowed something from somebody and haven’t returned it or we promised something to somebody and flaked out on them; or we were supposed to help in some way or give them something and we didn’t fulfill it, so there’s some kind of karmic debt in that way.

Those we harmed in the past or those who lust for this life’s body and life force.

This is talking about when we give to the spirits when we’re doing tonglen. There may be beings like that that we harmed in previous lives. We can think of people in this life that we harmed and things still aren’t clear between us. Do you have people in your life like that, where we’ve harmed them, and it still hasn’t been fixed up, so it’s not clean, clear energy between us? So, it’s that kind of situation carried over to another life; they still feel funny about us, we still feel funny about them, or [something] like that.

But we shouldn’t think that this kind of stuff is cast in concrete. If we think it’s cast in concrete, then it will be, and it will keep going back and forth, back and forth, back and forth between us. But as soon as one person says, “This other person is just an appearance, there’s no real person there, there’s no real harm,” then the whole thing’s cut. Or one person says, “Oh, this person may be trying to harm me but that’s because they’re suffering. May I have compassion for this person,” then you generate compassion, and that cuts the whole thing, too. We shouldn’t get this to make it too solid.

At the Buddha’s time, there was one couple who asked the Buddha, “We want to be married in our future lives, how can we do that?” So, the Buddha taught people how to do that. But I had one friend who’s really practicing very, very well. And then he met one woman and they fell madly in love. And he said to me, “It’s as if we were ‘soulmates’ from a previous life.” And I looked at him and I said, “I thought you were a Buddhist? Because if you think you have a ‘soulmate,’ some inherently existent person, and you’re an inherently existent person, and you’re predestined to be together again in this life, then I don’t think you’re a Buddhist.” That’s certainly not a Buddhist view, is it? They got married, I don’t know what happened; I never met her.

Audience: So, the Buddha taught that couple what they could do?

VTC: Yes, he said, “Create virtue so that you can have a good rebirth and then make prayers to be together in a future life.” But he said you have to create virtue for that to happen.

Using items we’ve given away

There’s still one little more chunk from Khensur Jampa Tegchok’s book. We discussed the taking and giving from before: taking from individuals, taking from the environment, giving body, possessions and merit to individuals, to the environment. So then the question comes, “Can we use the things that we’ve given?” Because we’ve just done taking and giving, and we mentally gave everything away, didn’t we? Unless you’re thinking, “Well, it was just a visualization. It’s my comfortable office chair, my office; I have the best office. I arranged when we switched rooms to get a good mattress. I have all that. I gave it all away when I did tonglen, but it’s still mine.”

If you’re thinking like that, then you haven’t really practiced taking and giving because you haven’t really mentally given up your grasping onto this thing. It’s just been a nice visualization of “I give my arm and my liver and my eyeballs and everything, but I’m certainly glad they’re all still mine.” No. You want to really feel when you do taking and giving that you’re giving up your attachment and clinging to these things, and you’re giving up your miserliness. When you give things, they really belong to the other person, they don’t belong to you anymore. You really want to cultivate that feeling, “I’ve really given it; it’s not mine.” If you really practice properly and you think like that, then you say, “Well, I’ve given everything away so can I still sleep in my bed? Can I still use my computer?” Actually, it never was your computer; it’s the Abbey’s computer. All of our computers belong to the Abbey. I bet you didn’t know that, even if it used to be yours.

So we wonder, “Can I still use these things if I’ve given them away?” Khensur Rinpoche says:

After we have sincerely dedicated and given to others everything we possess, what will happen if we use those things? If we use them with craving and attachment, and forget about using them for the benefit of others, that is a fault. If we use them with little craving, with little or no craving and attachment, but nevertheless, forget the welfare of others, there is still a fault, although it is not as bad. The point is that having dedicated our body, possessions, and merit for the benefit of sentient beings, we should use them with that thought in mind.

It’s like you’ve given these things away and you’re borrowing them back to use. You’re borrowing them back, so they still don’t belong to you. And since you borrowed them from somebody, when you use them, you should use them in a way that benefits the person that you borrowed them from. You’re borrowing the things from all sentient beings. We should have an attitude when we use different things that “This isn’t mine. I’m not using it with craving and attachment and I am using it for the benefit of sentient beings.”

If we remember to do this, it can help us so much, really so much. And this might be a thing, that if we’re really courageous, we might want to remind each other about when we see somebody else becoming quite possessive of something. We have to be very courageous if we’re going to remind the other person and let them remind us, because usually the time when they’re going to remind us is when we’re very full of attachment for something. They’re going to say, “Didn’t you give that away when you practiced taking and giving?” We’re not going to want to hear that. At that moment we do not have a Dharma mind; we have a craving and grasping mind. We’re going to say something nasty to them, even though they’re right, because didn’t we give it away when we practiced taking and giving? We also gave it away when we offered the mandala. When you make the mandala offering you’re giving the universe and everything in it, so it doesn’t belong to you anymore.

That doesn’t mean that you look at your friend and say, “Well, my friend has done taking and giving, and given everything away so now I can go use their stuff because I’m part of the people they gave it to in their taking and giving meditation.” No! You can’t do that. But when you use things, you have to think, “These don’t belong to me, I gave them to sentient beings or I gave them to the Three Jewels, and I’m just borrowing them back and using them.” How do you think that would help you, to think like that? Think of a situation. It happens on a day-to-day basis. I can think of a situation that happened the last few days, and how thinking like that would have helped you in that situation.

Audience: Your mind would be somewhat detached, you would relate to it more realistically, and you just wouldn’t have so much attachment to it, so it would free you up to use it in a more balanced way.

VTC: Can somebody give a specific example that happened in the last few days where maybe you were holding on tightly to something and how thinking like this would have helped you?

Audience: I cleaned up my bedroom a little bit the last few days and I found a small set of headphones to carry on when you travel. I thought “Hmmm. I have headphones already and then I remembered Lama Sopa was carrying her headphones from one home to another and sometimes forgets and I said, “I don’t need that headphone, but I could use it sometime in the future.” I know that I had this attitude the years before, that’s why I have had it since over five years but never used it. I just gave myself a look, wrote a note and gave her the headset and now I feel much more released.

VTC: That’s a very, very good example. Can somebody else think of an example?

Audience: About a week ago I couldn’t find my zhen. I looked everywhere. It started out in the afternoon, I went to the medicine meal, I retraced my steps, I went back to the hall, I went to the kitchen, I went to the dining room. First of all, thinking “You’re losing your mind Semkye,” second of all, “Somebody took it.”

VTC: Yes, the Boogey Man!

Audience: The Boogey Man took it! And I need my zhen.

VTC: He decided to get ordained!

Audience: I was actually getting kind of ticked off because I was afraid that I was losing my mind. I said, “No, you haven’t, somebody’s got it.” So then I said, “Okay, the worst case scenario is you go into the hall tomorrow and you’ve got your wool zhen, somebody will return it.” Then I find out later on that Venerable Chonyi had accidentally put it where the children had taken it and then brought it over to Gotami House. But I looked everywhere! My zhen was missing. It had my name on it, I know exactly what it looks like, and somebody took it because they weren’t paying attention. I was like, “Wait!” But I could see my mind looking even over something simple as a red piece of cloth that I imputed “zhen” on.

VTC: Yes. And at that moment, if you had thought I’ve given away already to sentient beings, if it turns up, it turns up. If it doesn’t, I’ve given it away.

Audience: There’s a mop that I really like here because I really like cleaning the floor. Sometimes the mop goes missing, which makes me crazy because that’s my favorite mop. Sometimes I have to hide it so that it doesn’t go missing. This past week as I’m back on this shift, (and I really, really like this mop) I put it outside to dry and I forgot. So then I’m looking in the closet, “It’s missing! I should have hidden it in my office.” Then I was coming back from Gotami House and I saw it. But it gets worse! Now it’s quite worn out because I really work it hard. And I got Venerable Tsultrim to buy a new head for it. So, the head and the mop are in my office right now.

Audience: Give it away!

VTC: It wasn’t yours to start with! We’ll check and see whether it was on the reimbursement thing or not.

So, if you think about it, it can be very helpful. In the same way, too, if you’re about to eat something that you know isn’t good for you, that you shouldn’t be eating, you can think, “I’ve given it away; it belongs to somebody else,” and that makes it much easier (maybe) to tear yourself away from the grasping at it. It can happen with a lot of different things. But it’s a good way to practice.

The vinaya set explains that there are many parasites living in our body. If we are alive, they will remain alive and if we die, so will they. When we eat, we should think that we’re doing so to keep them alive and think, “Now I will satiate them with food, in the future may I satisfy them with the Dharma.” This is one way to think while eating. I hope all those bugs like chocolate! If they like mayonnaise, they’re living in the wrong body.

In our meditation we have also offered all that we have to our spiritual mentors, the buddhas and the bodhisattvas; we might therefore think that we have no right to use those things.

Has anybody ever thought after you’ve offered things in your meditation that you have no right to use them? You’ve thought that? Good! Usually we don’t think that because we haven’t really given, but if you’ve really given it mentally then you might think, “Oh, I have no right to use them.”

However, since the holy beings’ aim is to accomplish the welfare of sentient beings, if we use the things we have offered to them for that purpose, there is no fault. This is similar to getting our food from the employer’s kitchen when we work for him. Since we are working for him, and accomplishing his wishes, it is fine to use the things required to do so.

So again, if we’re working for sentient beings, it’s fine to use the things that we have mentally given away, either to sentient beings or to the Triple Gem.

In tantra, we think of ourselves as the deity, consecrate the food before eating and then offer it to the deity. In this way, we accumulate great merit. If we do not have any of the above motivations, thinking about the welfare of others, and simply eat, drink and enjoy possessions for our own pleasure, there is the danger of accumulating a lot of negative karma. While if we use these objects for the sake of sentient beings, there is no fault and there is even much merit.

Usually we offer the mandala reciting words such as ‘I offer my body, speech, and mind of myself and others, our possessions and virtues accumulated in the three times to the spiritual mentors, Buddhas, bodhisattvas and meditational deities.’ When we practice giving and taking, we give away our body, possessions, and roots of virtue. Some people may then think that after we have given all that away, it is not good for us to use it because it does not belong to us anymore. This is not correct. If we use them with proper motivation, for the sake of others, there is no fault.

But we should think “I’m using the things that don’t belong to me,” even if they have your name on them. You’ve stitched your little insignia color thread on the socks, so instead of thinking “They’re my socks,” think “These belong to sentient beings, but I’m wearing them for the benefit of sentient beings.”

Maintaining bodhicitta

Now we will go back to Gomchen lamrim. We finished the heading that said, “The Training Based on the Works of Shantideva.” Now we’re on the next heading that is “The Way to Maintain It,” meaning the bodhicitta through ritual. That has: “Acquiring the ethical codes you have not yet acquired,” “Keeping what you have required from declining,” and “The way to restore if it declines.”

Under the first one about acquiring it, from whom do you take it? Here we’re talking about the bodhisattva ethical code, so it’s to be taken from someone who has, here it says “The vow of engagement.” I would say, “The ethical code of engagement.” The reason I don’t like “vow,” is because “vow” isn’t very accurate. When we say “vow,” we usually think of a Catholic vow where you have obedience, chastity and poverty, and it’s like, “I’m never going to do this.” Whereas in Buddhism, these things are all trainings that we practice. So, you look at them differently than if you’ve taken a vow. With a vow, especially if you’ve come from a Christian context, if you break it you’re going to hell. And we often think, too, of vows as something imposed on us from outside.

Whereas in Buddhism nothing is imposed on us from outside; we voluntarily take them. They’re guidelines to try and guide our mental, physical, and verbal behavior—to guide our actions and help us to train our body, speech and mind. The Sanskrit word literally can mean like an ethical restraint, where you’re just restraining yourself from negativity. If we just see it as restraint, though, not all the trainings fit in because many of the trainings aren’t just put in the negative “I shall not do this.” They’re also put in the positive: “Do this.” In that way, we say that it’s an ethical code, and then within that there are a lot of different precepts or different trainings or different guidelines, however you want to say it. I think using language that way eases how the mind relates to those things. Whereas if we think of “vow,” our mind sometimes can get really rather tight and rather closed about it. Then the other one is on what basis to take it.

Once you’ve trained your mind, on both shared path meanings,

This is referring to the path in common with the initial level practitioner and the path in common with the middle level practitioner.

Once you’ve trained your mind in that and you have great enthusiasm for bodhicitta,

This means that you’ve practiced these different meditations—either of the two methods to generate bodhicitta—you’re very enthused about it, and you want to really do the practice.

Then the next point was the ritual for taking it:

Maintaining bodhicitta with the preliminaries, the main part of the ritual, and its conclusion is excellent.

Here, I really think the chief bodhisattva ethical code that we’re taking is the one of engagement, but before you take that you want to adopt the ethical code of aspiration.

Aspiring and engaged bodhicitta

When they talk about the difference between aspiring bodhicitta and engaged bodhicitta, the aspiration is like, “Wow, I want to do that,” and engaged bodhicitta is, “I’m going to do that; I’m on my way.” There’s a difference between them. We hear a lot of people say, “Oh, I want to go to His Holiness’ teachings! I want to go, I want to go.” Many people say that, but that’s very different than looking at where he is teaching and getting the ticket and getting the transportation and doing all the arrangements and starting to go and getting there. We have to start with the aspiring bodhicitta, but eventually what we want to get to is the engaging bodhicitta. But we should start with something that’s easier; we don’t start with the most difficult thing.

Within the aspiring bodhicitta, which is the easier or the preliminary one, there’s two ways to do the ceremony. There’s doing the ceremony where just in the presence of your spiritual mentor you generate bodhicitta, and that’s it, you generate bodhicitta. That’s it. The second way, it’s the same ceremony but people in a big group can do it in different ways. Some people are doing it in one way, some people are doing it the other way. The second way to do it is you’re generating aspiring bodhicitta and you’re saying “I’m not going to give it up.” You’re not generating engaging bodhicitta at this first part; you’re generating aspiring bodhicitta: “I aspire to become a Buddha for the benefit of sentient beings.” One way to take it is you generate that aspiration in the presence of your teacher. The second way to do the ceremony is you generate that aspiration in the presence of your teacher and you think “I’m not going to give bodhicitta up.” You see the difference?

Both of those are different than taking the engaged ethical code. That’s a different ceremony. So, when you take it just generating bodhicitta, there’s no commitment, no nothing. But it’s very good to do that. If you’re ever in a big crowd when a lama is generating bodhicitta, go ahead and generate it as much as you possibly can. If you have some confidence that this is really the way you want to live your life and that bodhicitta is very important to you and that you don’t want to give it up, then do it and think, “I’m generating bodhicitta, but I’m not going to give it up.” If you do it that way, then there’s different guidelines for aspiring bodhicitta.

If you have the red prayer book on page 73, there’s the generating aspiring bodhicitta, the three verses. Those of you who have been to His Holiness’ things, these are the ones he always uses for generating bodhicitta; they’re quite beautiful. Then on page 75, you have the eight precepts of aspiring bodhicitta. These eight are for when, if you’ve generated bodhicitta and said, “I’m not going to give it up,” then you want to practice these eight. These eight are in two groups of four but the second group of four has a positive and a negative way of presenting it, so it’s kind of like twelve, but it’s eight. We’ll go through them now because I think it’s quite important to remember these things and to practice them.

Protecting your bodhicitta

The first part of it is “How to protect your bodhicitta from degenerating in this life.” So, you’ve generated bodhicitta, and you said you’re not going to give it up. How do you do that? How do you not give it up? The first thing is to remember the advantages of bodhicitta repeatedly. We covered the advantages of bodhicitta early on. What are some of the advantages?

Audience: Purification

VTC: Yes, it’s very strong purification.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: It is? It’s the doorway to the whole path? So that means hearers and solitary realizers aren’t on the path?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: It’s the door for the Mahayana path, the bodhisattva path. What’s the door for the Buddhist path, just the Buddhist path?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Taking refuge. This is different. What are other benefits of bodhicitta? Your realizations are going to come more easily. Yes, your life becomes meaningful. Yes, you’ve entered into the Mahayana.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, it makes the mind very joyous and happy and expansive. It pulls you out of your depression, your self-pity and all those “nice” mental states that we get sunk into. So, that’s the first thing to help you to prevent it from degenerating in this life.

Strengthening bodhicitta

Then the second:

To strengthen your bodhicitta, generate the aspiration to attain awakening for the benefit of all sentient beings, three times in the morning and three times in the evening.

To do this, you can just generate it in your heart, in your own words, or you can recite one of the verses of generating bodhicitta like we do right before the teachings all the time. “I take refuge…”: that’s generating refuge and bodhicitta, so you could do that one. If you’re doing different sadhanas, they all have different prayers for generating bodhicitta. In the Guru Puja, there’s a verse for generating bodhicitta, so you could use any of those or you can just generate the bodhicitta on your own. But to do it three times in the morning and three times in the evening. Each repetition you do of a prayer is a generation of bodhicitta. That strengthens it, because it’s about habituation and familiarity—the more we do something, the more it becomes stronger within us.

Always Working for Sentient Beings

The third is:

Do not give up working for sentient beings even when they are harmful.

What do you think about that one?

Audience: Now I do the purification once daily.

VTC: This one, maybe we have to purify on a daily basis. They say giving up bodhicitta is one of the worst karmas to create because when we generate bodhicitta and especially if we make the promise to benefit sentient beings and attain enlightenment for their benefit, if we then renege on the promise, that’s not so good. I mean, just even in common life, when we make a promise we should try and keep it unless there’s really some extenuating circumstances.

But here we’ve promised to benefit all sentient beings, and everything that happens to us in our life can be taken into the path going towards the enlightenment to do that. It isn’t like with an ordinary promise, like “I promised to drive you somewhere, but my car broke down so I can’t do it.” It’s not like that because there’s always a way to turn everything into bodhicitta. But here your mind just gets totally stuck, and it’s like “I am so fed up with this particular sentient being that I will lead everybody else to enlightenment but not this one because they criticized me; they humiliated me in front of a group; they bossed me around; they made fun of me and teased me.” They did whatever it is. “They didn’t smile at me.”

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: You want to say, “Just for this lifetime I’ll take a break from them and won’t work for their benefit.”

Audience: We take a break and then they’ll change their behavior in the next life cycle.

VTC: Yes, in their next life they’ll be a different person, and I’ll be a different person. So, I’ll work for their benefit then, but in this life, I’m done. No.

Audience: If there’s somebody that really pushes our buttons, and we do want to stay away from them for a life, if we still want to try to keep them in our heart, then is that the way to do that?

VTC: That’s okay. It’s like, “They push my buttons. I know I need to keep a respectful distance, but in my heart I really do want to be able to benefit them.” There’s still the intention, the wish to be able to benefit them. Giving it up is when you have no wish, you are done with them, basta finito; “I’ve had it.” You don’t want to do that; that’s extremely negative karma. The antidote to that is don’t give up working for them, even when they’re harmful.

Audience: I find it helpful, and I’m wondering if this is okay. I’m not giving up on them, but if I feel like I’m not capable of helping someone, I sometimes just kind of put them in the Buddha’s care in my mind.

Audience: It feels quite positive. It shows the recognition that the problem isn’t on their side, the problem is on my side.

VTC: Right. Or not even that the problem is on my side, that I’m incapable of it—I want to be able to do it, but I don’t have the specific skills right now. It’s not like, “I’m just totally incapable and never will be.” At this particular moment, I don’t know how to help them, but the wish to help them is still there. So then you offer them to the Buddha, and you put them in the Buddha’s care. That’s very nice because your heart is still connected to them. It feels very good, whereas if you just get so angry and upset that you just push them away in frustration, that’s very, very different. That’s what you want to avoid: the one that is just like, “Throw this person out the window. I hate their guts. I never want to see them again.” It’s all those kinds of things that people say when they get really mad at somebody else, don’t they? Maybe we do it. Have you said that to people?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: “I’m leaving. I’m out of here or get them away from me!” Or just the way people say, “Go to hell.” Yes, that’s a very nice thing to say to somebody else, isn’t it? Whether you mean it or not, it’s not something to say to others.

So, don’t give up working for sentient beings even when they are harmful. You still have to train the mind to keep some open mindedness, some forgiveness, some recognition that this person is not always going to be like this, that how they are right now is just due to causes and conditions, and it can change.

Enhancing bodhicitta

The fourth one is:

“To enhance your bodhicitta, accumulate both merit and wisdom continuously.”

This is what Nagarjuna also told us to do in Precious Garland; it’s the collection of merit, collection of wisdom. If we practice those two continuously, they act as a support for generating bodhicitta—being able to stabilize, maintain and increase our bodhicitta. You want to make sure you do those. That’s how to keep your bodhicitta from degenerating in this lifetime.

Abandoning the four harmful actions

Then it discusses how to prevent being separated from bodhicitta in future lives. Here’s where they have you abandon four harmful actions and you practice four virtuous actions. The first one to abandon is:

Now, why do you think that is a problem?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: How are you cutting the connection?

Audience: It feels like you’re cutting a connection because you’re going to have a breakdown of trust. When lying is involved that doesn’t set the stage for meeting in a wholesome way in the future.

VTC: If you lie to your teacher it indicates you’re not trusting them, and of course they can’t trust you. If we’re not open with our teachers, then how can they help us? If we lie to them and cover our stuff up, they can’t give us the kind of advice that we need in order to pacify our mind. It’s very important that we’re truthful with our teachers, even though sometimes it may be difficult and embarrassing, it’s very important that we are.

The second one is:

Causing others to regret virtuous actions that they have done.

What are some examples of causing others to regret their virtuous actions that you’ve either done or seen others do?

Audience: “Why did you give them that much money? They’re going to go out and blow it on something. They’re going to do drugs; they’re going to drink. You’ve got other more important things to do with your money than to give it away like that.”

VTC: Somebody is being generous and you say, “Why did you do that? That’s stupid. Keep it for yourself.”

Audience: Or similarly saying to someone, “You shouldn’t have apologized to them, they should apologize to you.”

VTC: Ah, yes.

Audience: Or saying to someone, “How can you ordain and leave your family without you?”

VTC: Yes, that’s a big guilt trip, isn’t it? Somebody wants to do something virtuous like ordain and you tell them, “That’s stupid; you’re hurting your family, and you’re wasting your time and energy.” That’s discouraging others from virtue. What else?

Audience: “Oh, you shouldn’t have stayed home and helped with that; you should have come to the concert with us. We had a good time”—something like that.

VTC: Yes. “Why did you stay home and meditate? Why are you going to that retreat? Come out with us, we’re having a good time.” There are lots of things like that. It’s not difficult to discourage other people’s virtue, actually. It’s not that hard to do so we have to be careful about that.

The third is:

Abusing or criticizing bodhisattvas or the Mahayana.

Criticizing the Mahayana is saying, “Buddha didn’t teach the Mahayana. It’s all made up; it’s just fantasy. There’s no way that you can become enlightened.” It’s even just saying that the path doesn’t work, that there is not that goal, or to say, “Mahayana wants you to give away your body. That’s ridiculous, you can’t do that.” So, it’s criticizing in that way or criticizing bodhisattvas.

The thing that they always say is you’re not really sure who’s a bodhisattva and who’s not because they don’t wear name tags and it’s not stamped in your passport or on your driver’s license—”Bodhisattva.” Some states want to do that now about immigrants, to include it in their driver’s license. But bodhisattvas don’t do that; you don’t get a bodhisattva driver’s license, so we don’t know. Before we talk to someone, we can’t ask, “Can I see your driver’s license? Let me see your passport? Do you have a visa to go to Sukhavati, or not? If you do then I’ll be careful what I say to you. If you don’t, well I’ll just let loose.” We don’t really know.

They say for that reason, be careful what you say to everybody and don’t get angry at anybody. I’ve spoken about this before, but I will say it again because this really is very, very confusing for people. What you want to avoid is getting angry and judgmental at the person but you can say, “That action seems inappropriate,” or “I don’t understand why that person did that action,” or “I would not have acted that way.” In other words, you don’t trash the person and criticize the person; you separate the person from the action.

But somebody could say, “A bodhisattva could do an action that looks really negative, but it’s something virtuous because they’re doing it for the benefit of sentient beings. And it’s working with somebody’s karma in a way that we have no idea of how it’s working, and it’ll actually come out as something good.” Does that mean then that we don’t say anything bad about anything at all? Like you say, “Well, maybe Trump is a bodhisattva. He’s doing all these things, and he’s a bodhisattva. Maybe it’s going to really turn out much better for the world that he’s putting all these policies into effect.” If he’s a bodhisattva and he’s working with karma that we don’t understand, maybe we shouldn’t say anything about his policies, we should just be quiet. Somebody could argue that way. Don’t you think somebody could argue that way?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, but for other people that’s not going to work for them at all. They may think, “Well, he may be a bodhisattva and maybe he’s doing these things in order to inspire people to stand up against it.” Because you never really know why a bodhisattva is doing something, do you? One person’s saying, “Well, he’s going to ban all these people from coming into the country, so maybe in the end, it’s really good for the world so I should go along with that policy.” And somebody else could also say, “Well, he’s a bodhisattva but the reason he’s doing this is to get everybody to think and stand up and say, ‘No, that’s not the kind of country we live in.'”

So, is one person right and the other person wrong? Is one person disrespecting a bodhisattva and another person respecting them? You really have to look at people’s intentions, don’t you? It’s not so clear. I think with some of these things, it’s very easy to go to an extreme and just say, “Well, I don’t know anything about who’s a bodhisattva, so I’m just going to not say anything to anybody about anything.”

But is that really working for the benefit of sentient beings? One person says, “Well, I’m just a sentient being; I can’t tell right from wrong anyway. I’ve been told so many times I have false appearances. I can’t judge what’s good and what’s bad. There’s two people beating up on each other, but I can’t tell. You know, they may be Vajrapani and Hayagriva and this is just a display of enlightened something. And I don’t know; all I have is distorted opinions and distorted perceptions, so maybe I shouldn’t do anything or say anything or intervene in anything.” What do you think? Could somebody think that?

Audience: It seems to me if you let your mind go to that place, you wouldn’t be practicing at all. You’d be too removed from it all. You wouldn’t be practicing.

VTC: Well, somebody could say, “Yes, I want to be removed from it all because I can’t handle it; I don’t know what to do.” So yes, it’s difficult to say because you could equally look at the situation and say, “That person’s just copping out, they’re not using their own wisdom.” They’re saying, “Because I don’t have a Buddha’s wisdom, I won’t use even the little bit of wisdom I do have.” If you don’t try and use your own wisdom, how are you ever going to develop that? And that’s legitimate, too, isn’t it? To say that, that could very well be true. I mean, to be a good Dharma practitioner, do you have to walk around like a zombie? “I’m just a bump on the log. I don’t have any ideas. I don’t comment on anything.”

Audience: Our teachers don’t model that.

VTC: Yes, our teachers don’t model that, do they? But then we get mad at them sometimes, because they do things that we don’t like or we get disappointed in them. Maybe not mad but disappointed, because “Why is my teacher doing that? They shouldn’t be doing that. They should be doing this.”

Audience: I think His Holiness’ advice is good on these kinds of things, which is to try to get the biggest perspective by really getting a lot of input from people and then use your wisdom.

VTC: So, instead of just backing off, instead of just plunging in full steam ahead, we can stop and get information and talk to a lot of people and maybe see how you can be useful in the situation.

Audience: On a practical level, if it looks like there’s going to be harm happening, of course step in, and if it is bodhisattvas, they’ll get over it.

VTC: Yes, you’ll get a tweet from Sukhavati. [laughter] It’s very interesting. I’m pushing this because it applies to how you relate to your spiritual mentor, how you relate to bodhisattvas. And different people have very different ways of practicing this. For some people, it’s like you never say anything about your spiritual mentor at all; you’re not mad but just even disapproval of what they’re doing or not understanding what they’re doing isn’t discussed. You have to see it totally as the Buddha’s action. Some people do it like that, and then that’s not the way His Holiness does it. So, it’s an interesting thing to think about. How do we navigate this in a way such that we keep our mind virtuous, we develop our wisdom and we don’t just become like a snail recoiling into our shell all the time for fear of saying or doing anything that might be considered anger, disapproval, because it says here you’re not supposed to do that.

Audience: There have been some spiritual Buddhist teachers that have done things that have been criticized as far as looking like poor ethics and such. And people have said things like, “Well, maybe they’re a high bodhisattva.” But to me, I just look at it as what most of us need is good ethics to be modeled. When I think about the possibility of someone say Donald Trump being a bodhisattva, if a bodhisattva were doing something that they knew was going to get a lot of sentient beings to criticize a bodhisattva, how would that be helpful to sentient beings?

VTC: Now that’s an interesting one. If a bodhisattva did things that they knew would invoke a lot of people’s criticism so that they would create negative karma, would they do that kind of action?

Audience: I’m assuming or I’ve been reading and studying that bodhisattvas are developing, as they go along their levels, these great abilities of skillful means to be able to meet the sentient beings according to what their capacities are. So, when you’ve got a bodhisattva going through these, thinking of them, affecting huge groups of people and huge amounts of sentient beings, they’ve got to be able to have the skill to do that so that it affects and influences them in a positive way and doesn’t stir up all the negativities. The skillful means would nix out a lot of the inappropriate things that bodhisattvas wouldn’t think of doing because they know the capacity of the beings with which they’re having a relationship. I would think that skillful means would kick in with their bodhicitta and their wisdom.

VTC: Yes—unless that behavior may make some beings upset. But it may really benefit other beings.

Audience: Yes, that’s where the skillful means hopefully can determine what’s going to be the long-term benefit, the short-term suffering—that whole beautiful combination.

VTC: Yes, you definitely have to have that. So, it’s something to think about: how you can live practically in the world. First thing you want to do is guard your mind against anger. If there’s anger in your mind, then for sure you’re going down the wrong street, so you want to protect your mind from anger. After that, if you can have a mind that isn’t angry but still look at the situation, then maybe you can practice developing some wisdom one way or the other.

Audience: I don’t have concrete quotes but when we do the vinaya, it’s so prominent how we kind of work on the basis of having guarded our afflictions. If we have not yet come to total control over them, then there is still the guideline of the vinaya that kind of sets us in the right direction. The vinaya we are doing at the Abbey: we are protected by that, and we make decisions within the vinaya that regards also people with whom we have contact, with whom we are living within our own community. I think that is very good.

VTC: I think that’s a very good point that we can get confused about, thinking “Should I do this or should I do that?” But we can always fall back on the vinaya, and it’s the bottom line on how to act. The bodhisattva precepts as well, adding them on because sometimes there may be an important concern that has to do with bodhicitta, where you can’t keep one of your vinaya things completely perfectly or literally. We can really fall back on the different ethical codes that we have to guide our behavior.

Audience: I was thinking we can go to the four reliances too, right, where you rely on the Dharma and not the person? I was thinking of this in the context of when we were Pure Land Marketing and they were talking about all these very famous Asian teachers who were appearing to teach the Dharma but there was like a mixed motivation. One of them had been a very famous teacher for a long time and then they saw very clearly something had changed. People change and they felt it was necessary to alert people, at least within their circle. Then whatever this person is saying is not in line with what is in the scripture, so we can go back there.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: But I don’t have to criticize him. He has benefited people tremendously, and recently he changed his behavior and is doing something that’s not appropriate.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: I thought they handled that quite skillfully.

VTC: I think just giving people a heads-up is important: “That isn’t in line with what the sutras say, or the tradition.” In other words, it’s not saying to somebody “They’re bad, they’re awful, don’t trust them, don’t go near them,” but just saying, “You need to be attentive and just check this person’s behavior, check what they’re teaching and if it coincides with the Dharma. Then you should make your own decision.” That’s a very good way to do it too so you’re not criticizing the person. But somebody could say, “But, they may be a Buddha.” About 25 years ago there were quite a few scandals in the Buddhist community. And one of the reasons people didn’t speak out is because they were told, “You’re breaking your samaya with your guru if you say anything. This person may be a bodhisattva and you create negative karma if you say anything,” so people were very, very confused. They said, “Something’s not right but we don’t want to go to hell for pointing it out.” That’s when His Holiness is just very practical about the whole thing and says, “You need to go and talk to the person if something is happening that doesn’t seem right.”

Contemplation points

Using the things we’ve given away in our visualizations

When we’ve genuinely done the Taking and Giving Meditation, Venerable says that a natural question arises: Having now given away our body, possessions, and virtue, can we use the things we’ve given away? Consider:

- When we’re doing the meditation, we really want to cultivate the feeling that we’ve given these things away; we’ve relinquished our attachment and clinging to them and that they now belong to others. As you’ve been doing the Taking and Giving Meditation over these past weeks, has this thought come up and, if so, have you experienced resistance to thinking in this way? What are the antidotes to the mind that still clings to objects?

- Consider the disadvantages of craving and clinging, and the advantages of relating to your body, possessions, and virtue without craving and clinging. Be sure to make this personal.

- Of course, we still need to use the objects we’ve given away: our bed, food, our body, etc, but it IS possible to use them in a healthy way, a way that benefits others. Venerable said that having dedicated them for the benefit of others, we should use them in that way. Think about some of the specific things you gave away during the meditation. Then consider how you might use them in a way that is beneficial to others.

- How might thinking in this way make you happier? How does it make you more mindful of what you’re doing and why? How does it benefit others?

- Resolve to cultivate this thought: that everything you have, even your body, now belongs to others; that you are simply a steward. Come back to it throughout the day, habituating this new practice of utilizing your body, possessions, and virtue for the benefit of others.

Aspiring bodhicitta

Before taking the bodhisattva precepts, we prepare our mind by taking the aspirational code in the presence of our spiritual mentor. Venerable Chodron went through the first seven of the guidelines for keeping our aspiring bodhicitta. Spend some time on each.

How to protect bodhicitta from degenerating in this life:

- Remember the advantages of bodhicitta repeatedly.

- What are the advantages of bodhicitta?

- How might remembering the advantages protect your bodhicitta from degenerating?

- To strengthen bodhicitta, generate the aspiration three times in the morning and three times in the evening.

- How might reciting the refuge and bodhicitta prayers in the morning and evening help protect your bodhicitta?

- If you are already doing this, how has it benefitted your mind and practice?

- How does it protect your bodhicitta from degenerating in this life?

- Do not give up working for sentient beings, even when they are harmful.

- When you’re having a difficult time with others, what thoughts can you generate to counter the desire you have to give up on them?

- Why is this point so important to the bodhisattva practice?

- Why does it protect your bodhicitta from degenerating in this life?

- To enhance your bodhicitta, accumulate both merit and wisdom continuously.

- Why does accumulating merit protect bodhicitta from degenerating in this life?

- Why does accumulating wisdom protect bodhicitta from degenerating in this life?

How to keep from being separated from bodhicitta in future lives:

- Abandon deceiving your guru/abbot/holy beings.

- Why is lying to your teachers and the holy beings a problem?

- How does being honest with them help you from being separated from bodhicitta in future lives?

- Abandon causing others to regret virtuous actions they have done.

- Think of personal examples in your own life where you’ve caused others to regret their virtue. Why is this harmful to you? To them?

- Why does abandoning this help you from being separated from bodhicitta in future lives?

- Abandon abusing or criticizing bodhisattvas or the Mahayana.

- What does it mean to criticize the Mahayana? What does it meant to criticize bodhisattvas.

- Venerable made it a point to say that this doesn’t mean that seeing everyone as a potential bodhisattva, we say and do nothing when we see harm in the world. Consider how to live practically in the world, how to keep this aspiration while still working for change to benefit sentient beings.

- Why does abandoning this help you from being separated from bodhicitta in future lives?

Conclusion: If you have already taken the bodhisattva vows or aspiring bodhicitta with a spiritual mentor, allow this contemplation to reinforce your virtuous goals and aspirations as you move throughout your day, resolving to continuously cultivate and never abandon bodhicitta. If you have not yet taken aspiring bodhicitta, consider the benefits of doing so. Even if you are not ready at this time, cultivate a feeling of appreciation for those who have, consider the benefits of doing so, and generate a wish to take and follow these guidelines at some time in the future.

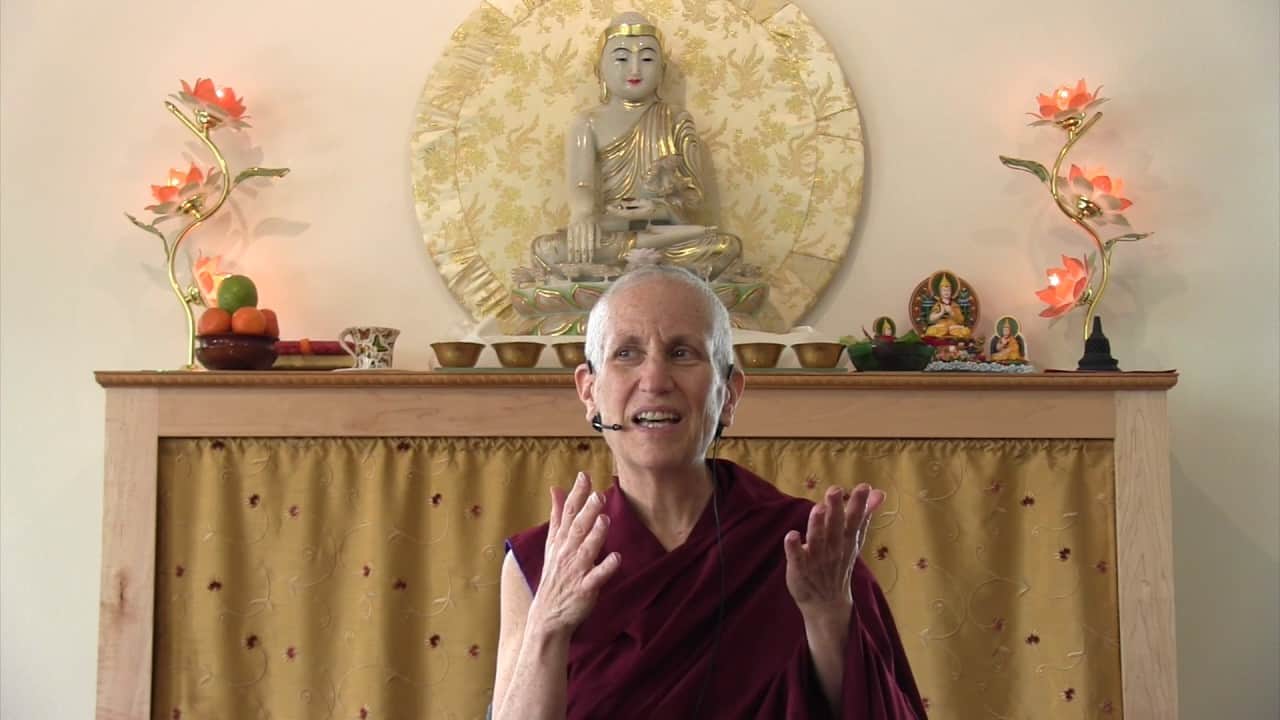

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.