The four types of clinging

Part of a series of teachings on a set of verses from the text Wisdom of the Kadam Masters.

- Clinging to sense objects

- Clinging as an increase in craving

- Clinging to views

- Ritual as a way of transforming the mind

Wisdom of the Kadam Masters: The four types of clinging (download)

We’ve been talking about the line,

The best sign of higher attainment is a decrease in your attachment.

We talked about just general attachment in daily life, and then last time I talked about craving and the different kinds of craving: craving for sense pleasure and rebirth in the desire realm, craving for existence (meaning rebirth in the material and immaterial realms where you have very sublime states of concentration), and then craving for non-existence (which means for everything that we don’t like to go away, or in extreme cases for the self to cease).

Then there’s still yet another kind of attachment. (Attachment, there are lots of kinds of attachment, because we have lots of attachment.) This one’s clinging. There are four different kinds of clinging. When we break it down into these groups they don’t encompass all the different kinds of craving, and the four don’t encompass all the different kinds of clinging.

In terms of clinging, again we find our old favorite, clinging to sense objects. Nice things, smells, sounds, tastes. touches, reputation, honor, praise, all these kinds of external objects, and so really clinging very strongly to them.

Clinging here is usually talked about as an increase of craving. We had the ordinary attachment to sense objects, and then we had the craving for them and it’s getting a little bit stickier. And then clinging, and we’re like [claps hands together] “gotta have it.” So there’s that.

The next three are actually clinging to different views. We don’t always cling to external objects or existence in samsara, we cling to views. And this can be especially pernicious when we cling to wrong views.

The second kind of clinging is just called clinging to views. This means clinging to all sorts of wrong views except the clinging to a personal identity and clinging to bad ethics and observances, which are the third and fourth types of clinging, which we’re going to come to. The second one includes all the other wrong views. These wrong views, it’s not voting for the wrong person. That’s not what we’re talking about. (Although I could extrapolate on that for quite a while, as you know. But I will refrain myself.) Here we’re talking about views that matter for spiritual practice. For example, if we say there’s no such thing as karma and its effects, meaning that our actions have no kind of ethical dimension, you can do whatever you want and it’s not going to affect what you experience. That’s a pretty wrong view. Or saying sentient beings are inherently selfish so talking about bodhicitta is just fairy tales. That’s a wrong view. I could go on and on: that there’s a permanent creator, that there’s no such thing as the Buddha, just on and on. All these kinds of wrong views that if we follow them we go down the wrong spiritual path, and we don’t gain any genuine realizations. What they call it is you gain “wrong realizations.” Which is kind of an oxymoron, but that’s what they say.

Then the third one, this one is clinging to views of a personal identity. It can start with clinging to a permanent, unitary, partless self that is independent of the aggregates and is the thing that carries the karma. It could include clinging to a self-sufficient, substantially existent self which is like the feeling we have that there’s a “me” that can control our body and mind-—the controller. We’re really into that one. And then the much more subtle clinging to self, when we think of the self as inherently existent, that’s not dependent on any other factor, including term and concept. Totally independent even of the mind.

All those kind of wrong views keep us firmly entrenched—especially the one of the view of the personal identity—keep us very entrenched in samsara, that’s the root of all the other afflictions.

Then the fourth type of clinging is another specific kind of wrong view which is…. This one is really hard to get a good translation that satisfies everybody, but what it is it’s like clinging to bad ethics and then observances. In the Tibetan tradition, they talk about it as bad ethics: thinking that it’s okay to steal in order to feed your family, it’s okay to kill to get rid of the infidels, these kinds of things. Things that are unethical we think are ethical. And also observances. Here it refers to, I guess, some practices they did in ancient India. I remember one of my teachers saying that if you jump on a trident and it comes out the center of your head then that indicates that you attained realizations or liberation. I don’t think that’s a good way to pass the test. But there are all sorts of views about what constitutes the path to liberation. So, wrong views about that.

In the Pali tradition they also include—and here I think this makes a lot of sense—wrong views about rituals and ceremonies. And considering that Buddhism existed within a Brahmanical society where doing the ceremonies and the rituals exactly 100% perfect was really emphasized over transforming your mind. So you had to pronounce everything correctly, and do the ritual correctly, and that was the path to liberation, that’s what accumulated good karma and whatever else constituted the path. Having that kind of wrong views about rituals and ceremonies, which I think is very easy to have in our culture as well, because it’s, “Okay let’s just do this ceremony and the ceremony itself has power and will change our karma or get us to enlightenment,” and so not seeing rituals and ceremonies as actual ways to transform our minds, but seeing them as being in and of themselves that path.

And that one it’s easy to kind of slide into, especially when we’re in a tradition that has a lot of rituals, and you can chant all day. I remember staying at one of the Tibetan nunneries on one of the major holidays, we chanted from morning until evening. Really, literally. Constantly. Broke for lunch and bathroom breaks and that was it.

If you don’t transform your mind, thinking the ceremony itself has some kind of inherent liberating power, is not really correctly following the path. So that is the fourth type of clinging.

To sense objects, to wrong views (except the two wrong views that are the third—clinging to the view of a personal identity, and the fourth one—clinging to a view of bad ethics and observances.) Whereas those two are misunderstood.

It’s important to understand this because often we think of attachment especially in terms of sense objects because that’s what’s so blatant in our lives. But also we can really get very attached, and crave and cling to, a lot of wrong notions. And that is very serious in our Dharma practice. And here again, we circle back to, remember, Nagarjuna’s verses in “Precious Garland” about the cows, one following the other, and the first one taking the wrong path leading it over a cliff or into a jungle, and how dangerous. That means following somebody who’s teaching wrong views. So how dangerous that one can be.

Attachment is a difficult one. Anger’s much easier to see as a fault. Especially other people’s anger. That, no doubt about it. But our own attachment? Much more difficult. That’s why on Friday night I asked you what are the defects of attachment—and here we spoke specifically about attachment to people—but it’s so important to think about these things and come up with the disadvantages yourselves.

Audience: When you talk about attachment to sense objects I’m wondering where the attachment to just the feeling of pleasure comes in….

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Actually it’s the feeling that we’re more attached to, but we think the feeling exists in the object, so the two are kind of conflated. Because in our mind we think “I want chocolate cake.” Because we think that the pleasure is inside the chocolate cake. And then similarly we may think, “Reputation, praise, aren’t those more inner things to be attached to?” But they all come by means of external objects—hearing sounds, people’s voices, reading what they write about us in newspapers or wherever. So it comes down to external communication like that.

To return to attachment to sense objects, here we have to really learn to differentiate what we want from what we need. Because we often say, “I need this,” when it really means “I want it.” Some things it’s good if we have them, but if we don’t have them we can still live. And here I’m talking about really basic things. We need enough food to stay alive. We don’t need lots of delicious nourishing food. It’s helpful, especially the nourishing part. The delicious part is going into the luxury area. Of course, if it’s not delicious then you don’t eat it, so you get malnourished. Unless you’re really desperate. But to really start asking ourselves what are our wants and what are our needs, and what are practical things that we can use and what are luxury items that we don’t really need to have. Because in this country we’re so used to…. We need luxury items, don’t we? And we don’t really need luxury items. Once you’ve lived in a third world country you realize that you don’t need so many things that you think you need.

Audience: What is the demarcation point where [inaudible] the mind is going from craving to clinging.

VTC: Oh, when you go from craving to clinging? It’s the intensity. In terms of sense objects, it’s the intensity. And then next time I’ll talk about craving and clinging at the time of death. That’s another type of craving and clinging.

[In response to audience] It doesn’t matter how long the puja is, if you’re transforming your mind through it, that’s good. That’s Dharma practice. But when you think that I don’t need to even look at the state of mind, I just need to do the puja because the puja itself will have the power—yes, like a magical thing. But pujas are definitely designed to transform your mind. But if you just kind of go in and you’re just like ‘blah blah blah” then it’s something else.

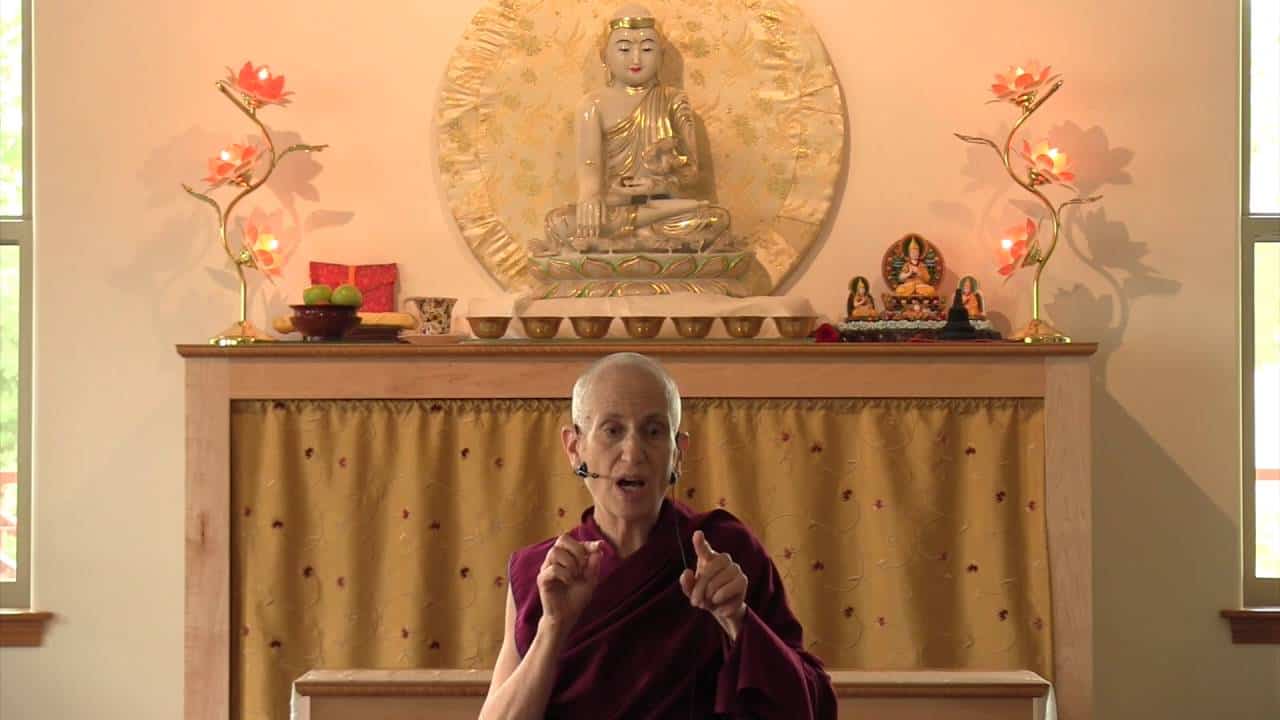

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.