Overcoming self-centeredness

Part of a series of teachings on a set of verses from the text Wisdom of the Kadam Masters.

- Seeing how the self-centered mind limits us even in spiritual practice

- Becoming aware of the karma we create under the influence of the self-centered mind

- The benefits of cherishing others

- Practicing wise compassion

Wisdom of the Kadam Masters: Overcoming self-centeredness (download)

A while ago we were in the middle of discussing a text by some of the Kadampa masters—Khuton, Ngok, and Dromtonpa—and they asked Atisha, “Of all the teachings of the path, which is the best?” And then Atisha gave some very brief slogans—which ones were the best—and we were talking about the third one, which was, “The best excellence is to have great altruism.”

When explaining that I was talking about the methods for developing bodhicitta, and we went through the seven-point-cause-and-effect method, and then the second method, equalizing and exchanging self and others. I think we were just at the point where we were talking about the disadvantages of the self-centered mind and the benefit of cherishing others.

We recently discussed this at the retreat, but it never hurts to have a reminder, because the self-centered mind is active every day, so we need to remind ourselves every day about it.

When we talked about it in the retreat, I just opened it up for discussion, and had people mention what they saw from their own lives of the disadvantages of the mind that thinks, “I’m most important. I’m right. I’m going to win. My happiness is more important than anybody else’s does. My suffering hurts more than anybody else’s does.” This mind that is constantly thinking about our own happiness and importance to the point of really it influencing our spiritual practice, too, so that we think only of our own liberation, and don’t think of the liberation of other living beings. When the self-centered mind is like that—which is a much subtler level of self-centeredness, it cuts the opportunity to enter the bodhisattva path, it cuts the opportunity to become fully awakened buddhas, because we become satisfied with our own nirvana, what they call “personal peace.” We just work for our own liberation, say, “That’s great! Wish everybody good luck, and I hope you get liberated but I’m going to enjoy my own liberation.” I’m being a little bit crass, but it kind of comes to that in some way. So we really want to avoid that kind of attitude at all costs.

The grosser kind of self-centeredness works very well with our afflictions, especially attachment, anger, pride, and jealousy, as well as all the other ones, because the self-centered mind is just looking out for our own wellbeing. Under the influence of this mind looking for our own wellbeing, we don’t like to listen to anybody else’s advice, even if they give it with a kind mind and are trying to help us. We always try and get the best for ourselves, give the worst to others. Whenever we make a mistake we try and justify it rather than admit it. We hate blame, we love praise. As somebody once told me, we want to look responsible but we don’t want to be responsible. All of this is very much the function of that self-centered mind. And under its influence then we create a ton of negative karma. And of course, that negative karma, who does it harm most? It harms us in the long term. Our self-centered actions definitely harm others right now, but then we implant in our own mind, karmic seeds that will ripen as painful results for ourselves. That’s a big reason to give up that self-centered mind, because we want to be happy, and we want other people to be happy.

Along that light, then, benefiting (or cherishing) others is a way to really create a lot of good karma because we’re putting others’ happiness before our own, and being considerate of them, and wanting the best for them, instead of just always being on the lookout for what benefits ourselves.

Cherishing others, I emphasized in the retreat, it doesn’t mean that we do everything everybody else wants, because sometimes what people want is not wise—it’s not good for them, it’s not good for us. Cherishing others is an attitude that we want to develop in our meditation, and then how we act it out in our day-to-day environment, we have to have a lot of wisdom for what that means. Otherwise we get what people call “Mickey Mouse compassion.”

I remember when I lived in the Dharma Center in France we did a skit one time for Zopa Rinpoche when he was there and it was about Mickey Mouse at Vajrayogini Institute, and Mickey Mouse ran the office. So somebody came in and said, “You know, I’m really broke and I need some money for some alcohol.” And Mickey Mouse just gave him some money from the Institute.

That’s kind of Mickey Mouse compassion. We think, “Oh, cherish others, whatever they ask for we give to them.” No, we really need to have quite a bit of wisdom in doing that. But it comes from an attitude, which is the attitude of cherishing others. It’s that attitude that we’re trying to focus on.

Sometimes we go to the behavior too quickly without working on the attitude behind it. All these meditations are working on the attitude (or emotion) behind it. When that is pure, when that’s solid, then the behavior comes along without so much confusion.

After seeing the disadvantages of self-centeredness, the benefits of cherishing others, then we exchange ourselves for others. This doesn’t mean I become you and you become me and I get all the money in your bank account and you get all my bills. It doesn’t mean that. It means that what we’re exchanging is who is of foremost importance. We do that by actually exchanging the labels so that when we say “I” it’s speaking of the “Is” (plural of “I”) of all other sentient beings. And when we say “you” we’re looking at ourselves as seen from the “Is” of other sentient beings who see us as “you,” as other.

Shantideva describes this very interesting practice that you do then. Your new self (which is now others) looking at your old self (which is others—which used to be others but you’re calling “I” now….)

What you’re doing is you’re being sentient beings looking at the “I” that you used to be—put it that way, that’s simpler. You’re being sentient beings looking at the “I” you used to be as sentient beings would look at your old “I”. And then you practice getting jealous of your old “I”, getting competitive with your old “I”, and getting arrogant over your old “I”.

Getting jealous would be you look at your old self and say, “Oh this person, they’re so much better, but they don’t do anything…. They have all this riches and stuff like that, but they don’t really do anything to serve sentient beings. Look at them.”

And getting proud over our old “I” is, “Oh, I’m so much better than that person, they just think they’re wonderful but they’re actually—can’t do very much right.” So you get proud.

And then you compete with your old “I”. “Oh that one thinks they’re going to get the best of me, but I’m going to work hard and I’m going to beat them out.”

It’s a very difficult way of thinking. But it’s quite interesting. You start to look at yourself and how you might appear in the eyes of others, and that leads you again to see the faults of self-centeredness and the benefits of cherishing others. Because you realize that when you’re putting yourself up, others would be jealous of you and they’ll point out all your faults. And when you’re putting yourself down, others will be arrogant over you and then criticize you for all your faults. And competing, we know what that is.

It’s a funny way of thinking, but it can be very effective for really attacking our self-centered thought and seeing how dysfunctional it is.

After that, then the next step is we do that taking-and-giving meditation. That’s where we’ve exchanged self and others, so we imagine now taking on the pain and misery of others (which we’ve called “I”). We take on their pain and misery, use it to destroy our own self-centeredness, then generating that. So that’s compassion. Then, with an attitude of love, wanting to transform and multiply our body, possessions, and merit and share that with all other living beings.

That, too, is a very profound meditation. People often teach it now very early on, and when you do that it sounds really good: “Oh, I’m taking on others’ suffering and I’m giving them my happiness.” But unless you’ve really done the preceding meditations—of equalizing self and others and the disadvantages of self-centeredness, benefit of cherishing others, exchanging self and others—if you haven’t done that, then the taking and giving, it doesn’t really change your mind much. But when you’ve really done those others and you’re really thinking of getting outside yourself and not looking at yourself and your own benefit all the time, really cherishing others, then when you do the taking and giving it wakes you up and it can be a a bit scary. And if it’s scary, it means that it’s really hitting the self-centeredness. Then if it’s really hitting the self-centeredness then we have to go back and see, “Okay, what’s the self-centered mind clinging on to that is causing this impediment in doing the meditation.” And then we have to work on that.

But if we’re just sitting there very comfortably: “I’m taking on the cancer of everybody, I’m giving them my body, and merit, and possessions, and I feel lovely….” Then it’s not touching us, is it? We’re just feeling kind of nice about ourselves. And this meditation, actually, if you do it seriously, it wakes you up, like, “I don’t know if I want to give my body away.” And then we see, “Wow, am I attached to this body.” Then you have to go back and really see the defects of being attached to this body, and the benefits of cherishing others.

When you really have strong renunciation of samsara you want to get out, and then you say, “Oh, I’ll take on all others’ suffering and I’ll stay in samsara, and I’ll give them all my merit, and they can get enlightened.” This is opposite to the mind of renunciation that says, “Hey, I want to get out of samsara, I want liberation.” And you go, “Ahhhhh. Hey, I want out, I don’t want to stay in this hell-hole anymore.” And it makes you see the difference between aspiring for liberation for ourselves alone and really aspiring to become a buddha for the benefit of others. Quite a powerful meditation.

If you want a very beautiful and expanded explanation of this meditation, the best one I’ve ever seen is in Transforming Adversity into Joy and Courage, by Geshe Jampa Tegchok. It’s in Chapter 11, and it’s a beautiful explanation of the taking and giving meditation.

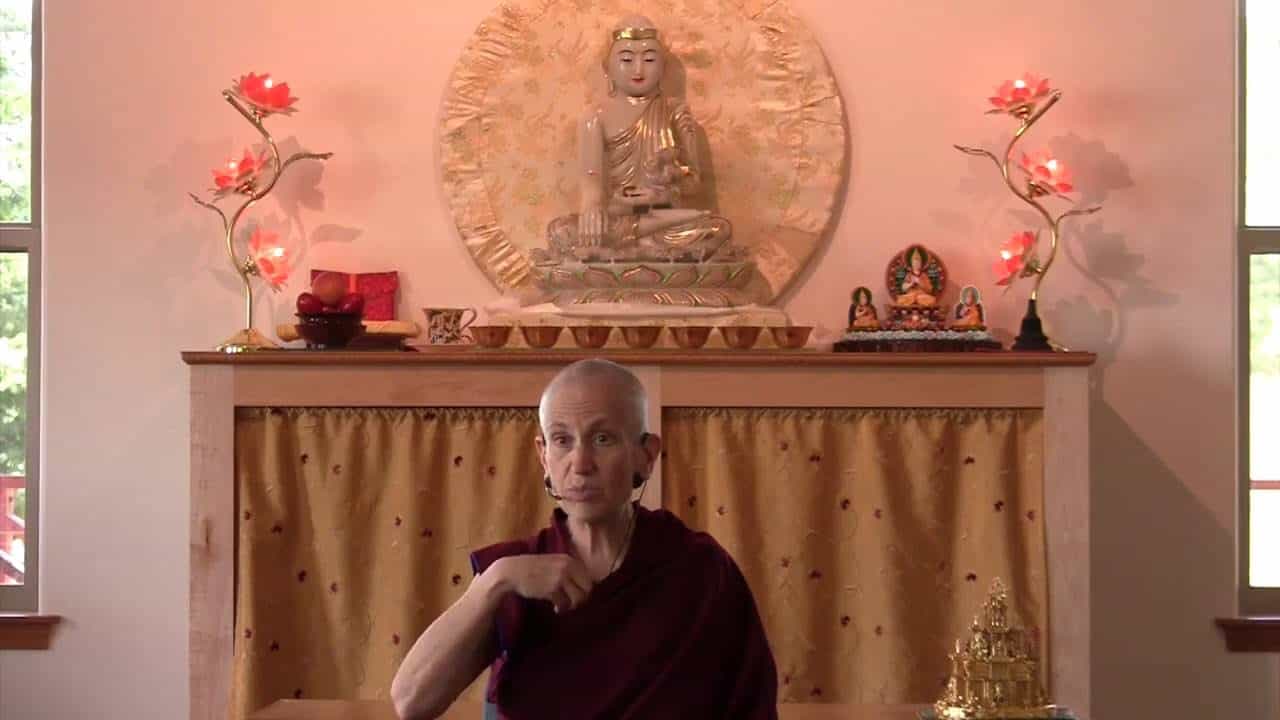

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.