Working with attachment to food

Part of a series of short talks about the meaning and purpose of the food offering prayers that are recited daily at Sravasti Abbey.

- Methods to work with the attachment to food

- Considering the causes and the results of the food that we eat

- Offering the food is a method to curb the attachment

- Mindfulness while eating

We’ll continue with the discussion of food and eating and how to work with attachment when we’re eating.

One way they recommend, which works extremely well…. We eat the food and we chew it. When it’s on the plate it looks so delicious and we have so much attachment. Then we chew it. If we spit out the food we chewed would we eat that? It looks kind of disgusting, doesn’t it? But it’s interesting because one minute it’s beautiful on the plate, then thirty seconds later in our mouth, if we spit it out it would look disgusting and we wouldn’t eat it.

If we think about what the food looks like going down our digestive system, and what it looks like when it comes out the other end, then certainly we wouldn’t have very much attachment for it, would we? So, if we’re having a lot of attachment for food it’s very good to remember that the food is not inherently existent food.

First of all, its causes. It came from the dirt. We certainly wouldn’t go outside and go in the garden and eat some dirt. Yet that’s where the vegetables came from, the fruit came from. Then of course after we eat it it doesn’t look very beautiful. It’s kind of strange, isn’t it, that you have the causes of the food and the results of the food, both of which we would not eat and are not very appetizing, but somehow in the middle we think that the result of the cause and the cause of the result somehow has its own inherent deliciousness in it. Isn’t that peculiar? It’s very strange how we living beings think. It really doesn’t make much sense when you think about it. So that’s a very good way to reduce our attachment to food.

Of course, sitting down and doing the meditation that we do when we offer it also reduces the attachment to it because we give it away. We’ve offered it to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, so it’s certainly not very becoming, nor appropriate, to be attached to what belongs to the Buddha. That wouldn’t create very good karma, would it? It would be like offering something on the altar and sitting and salivating over it, “Buddha, please give this to me.” We offered it, it no longer belongs to us. Why are we getting attached to it? That’s another antidote that’s helpful to reduce the attachment to food.

Like I said before, attachment to food…. Sometimes when you’re new to the Dharma it seems like, oh, that’s your worst attachment. What they say is attachment to food is nothing compared to attachment to sex, attachment to reputation, attachment to love and praise and approval.

Once I was at one of our Western Buddhist Monastic gatherings. We were talking about training our mind and how we train our mind and the difficulties. There was one Theravada monk who was explaining how he was living in Thailand and the people offer these beautiful meals to the monks in Thailand, and he just loved mangoes. Mango would be offered every day and he would just see this amazing attachment to the mango come up. He talked about how much he had to work with his mind to deal with the attachment to the mango, and calm his mind, and so on and so on.

Then I was the next one who spoke and I said, “You know, for me, if working on my attachment to a mango was the biggest thing I had to do in my early years of training, that would have been a breeze. Instead, my teacher sent me to be the disciplinarian of the macho Italian monks.” And then I talked about my experience working with them. It’s very clear, attachment to food would be nothing than working with attachment to… You know, you want praise and approval, not blame for things you didn’t do. And not people writing your teacher and telling him that you’re the worst thing that ever happened to the Dharma center, simply because you wanted people to go to puja instead of work.

Anyway, what I’m saying is don’t get too wigged out about your attachment to food and go into crisis about it and say, “Ahhh, I’m so attached to food this is….” Work with the attachment and the anger that causes the most difficulties in your life. And also gently work on your attachment to food. I say this because I’ve seen too many people go into some kind of thing about, “I can’t eat because there’s so much attachment.” That’s just not very healthy at all.

Mindfulness

I wanted to talk a little bit about mindfulness while eating. It’s quite interesting. I used to teach at Cloud Mountain Retreat Center, as many of you know, and they host retreats by Zen people, by the Theravada people, and also by the Tibetan tradition people. My friends there would tell me that you could tell which tradition retreat it was by the way that people ate. The Zen people would walk in, sit down, do their prayers chanting, and then eat, and the food would be gone in five minutes. Gone, finished, nothing. Chant the end of the thing, and leave. The vipassana people, Theravada people would come in, walking extremely slowly, lifting, pushing, placing. Finally they would get to their chair and sit down. Then they would pick up the fork up extremely slowly, with the food on it, and put it in their mouth, and then…. (chew slowly). And the meal would last 45 minutes to an hour. Mostly an hour, because they were mindful of the taste of every bite, everything. The Tibetans would walk in, normal pace, do their prayers, sit down, eat, finish, everything normal, and leave.

Here you see, within this, how different traditions have different practices to help us deal with the attachment. The Zen people eat very quickly because when you eat quickly there’s no time to be attached to it because everybody has to finish at the same time and you cannot be the last one. So you shovel it in. The Theravada people you eat very slowly. This is the insight people. My Theravada monastic friends don’t usually eat like this. But the insight people. Very slowly, chew, to be extremely mindful of each, the taste, and the movement and all. And when you do that, really, you want to swallow already because the feeling of this food in your mouth for so long is blah. Can I swallow it and drink something? You really lose the attachment. And also, you realize that when you sat down you had this whole mind that thought you knew how it was going to taste, and when you actually eat it it doesn’t really taste much like you thought. Maybe the first bite does, but really, as you chew it and you feel this goo in your mouth over time, and the same taste, it’s like, this isn’t how I thought the chocolate cake was going to taste. Or the spaghetti. Whatever it was. It’s quite interesting to see these different ways of working with the mind when we eat.

Both of these ways work, eating very quickly, eating very slowly. I think eating normally also works. Personally speaking, I think our motivation for eating is really the key thing, and much more important than necessarily being aware of the movement of the jaw as you eat (each bite, as you chew, each mastication). That word is enough to turn you off. It’s helpful to pay attention to this and to decrease the attachment, but to really come back to the visualization we’re doing, offering the Buddha food and the buddhas sending out light throughout our body. That’s another way to not have attachment to it, because we’re offering it, it doesn’t belong to us. So you eat normal speed and like that.

There are many different ways to eat mindfully. Mindfully doesn’t have to be slow. And I think mindful of our motivation when we eat is quite important. The five contemplations really are talking about mindfulness when we’re eating.

In the Chinese tradition when they do the five contemplations, you don’t just recite them at the beginning and then forget them, but while you’re eating you’re actually mindful of those. You’re mindful of the causes and conditions and the kindness of others by which we receive the food. We’re mindful of the food as medicine. We remember that our purpose in life is generating bodhicitta and attaining full awakening, so we have the resolve to eat with that kind of intention. Those five mindfulnesses, too, are another way to eat mindfully.

I’m saying this because the word “mindful” is so commonly used now that hardly anybody knows what it means anymore. We could call those, instead of the five contemplations, the five mindfulnesses before eating.

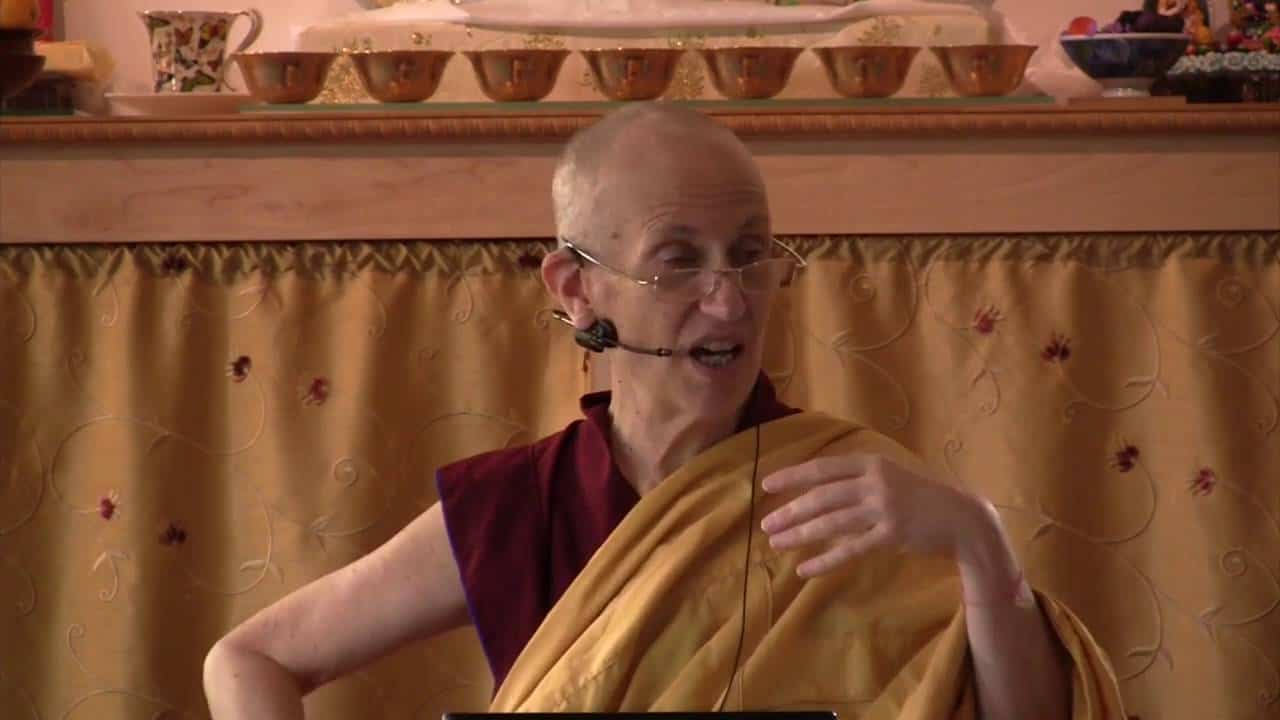

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.