Meditating on the four establishments of mindfulness

A series of teachings on the four establishments of mindfulness given at Kunsanger North retreat center near Moscow, Russia, May 5-8, 2016. The teachings are in English with Russian translation.

- Two ways to meditate on the four establishments of mindfulness

- Meditating on the common characteristics of the four

- Meditating on the individual characteristics of the four

- How the four establishments correspond to the Four Noble Truths

- The methodology of learning the Dharma is different from learning other things

The four establishments of mindfulness retreat 02 (download)

Good morning, everybody. I hope you’re well. I wanted to tell about some practices to do when you first wake up in the morning and when you go to bed at night. Because this makes your day, kind of, whole. And then, after that, we’ll do some meditation and go into the teachings.

When you first wake up in the morning, before you even get out of bed, generate your motivation. You want to think, “Today as much as possible, I’m not going to harm anybody.” So, not harming them physically, not speaking to them in a mean way, and really doing our best to avoid negative thoughts about others.

Another important thing to motivate us in the morning is to think, “Today, also, I will be of whatever big or small benefit I can be to others.” So, if you’re going to work, then this is the time to really transform your meditation for going to work and think that you’re going to work to benefit others that day, instead of, “I’m going to work because I want some money.” Of course, you need to support your family, but you want to make your motivation more than that, too. Think of the people that you may meet that day. It might be customers, clients, colleagues, your boss, your employees; if you’re a student, you’ll meet your professor, you’ll meet other students; and just really think, “Today, as much as possible, may I do things that are beneficial to them.”

Sometimes this may be something small, like giving somebody a piece of paper if they need it. Sometimes it may be something larger, like maybe one of your colleagues has an emergency at home, so you take on some of their tasks for the day. Or it might be that your mother, father, or some relative needs help with an errand, so you help them out with that.

What I also tell people is the best way to show your family that Buddhism is something good is to take out the garbage. Some of you made faces, like, “I’m above taking out the garbage.” None of us are above taking out the garbage. We make the garbage, so we should take it out. But so often in our families we let other family members do the dirty work. Yes, we let them cook, we let them wash the dishes, we let them do the laundry, we let them take out the garbage, and then we come, and our role is to eat and make everything dirty, and that’s it. “I’m working for the benefit of all sentient beings, I’m going to attain enlightenment.” So, we should put our compassion into practice and try to be helpful to the people we live with. Especially if you’re trying to impress your parents with the value of the Dharma, this will be it. You go and take out the garbage, and then your mother’s thinking, “Wow! Thirty years I’ve been trying to get my son to take out the garbage. I like Buddhism.”

Have a motivation to be of benefit to people. Also to strangers that you meet along the way during the day, be pleasant to them. If you have to go to the grocery store, the bank, or you have to make a phone call, email, or WhatsApp people, speak politely to the strangers that you encounter and thank them for the work they do.

And then the third motivation to generate in the morning—first one was not to harm, second one was to benefit—third one is to really hold onto and increase your bodhicitta motivation during the day. This is the motivation to become a buddha for the benefit of all living beings. If you cultivate that motivation in the morning, thinking, “I want to do everything today with that motivation,” then everything you do becomes very meaningful, and you create a lot of virtuous karma. If you’re afraid that you won’t remember to do the motivation in the morning, put it down on a slip of paper, put it by your bedstand, put it on the mirror in the bathroom, put it on the refrigerator door, and that way you’ll remember.

Try and recall your motivation during the day. Sometimes it’s helpful to use something that happens frequently throughout the day, maybe the telephone ringing or receiving a text message. Whatever it is, whenever you get that signal, then you come back to your motivation for a moment and renew it. This will make a difference in how you feel during the day, your emotional state of well-being, and it will also make a difference in terms of the karma that you create because you will be abandoning nonvirtue and creating virtue, which is so important for our spiritual practice.

In the evening, review the day and see how you did, see if you were able to act according to your motivation or not. In the areas where you were, then pat yourself on the back and rejoice in your merit. In areas where maybe you didn’t do so good, then do some purification with the four opponent powers.

Maybe during the day at work you started to get angry at one of your colleagues or maybe your boss. You were mad, but you succeeded in not saying anything awful. In that case, you would rejoice at being able to refrain from harsh speech, because that’s something that’s very good. Maybe normally you would have just lost your temper and shouted something or insulted somebody, but you were able to abstain from that, so you rejoice. But on the other hand, you did get angry inside, so that part needs some purification. That’s where, in the evening, you would take out one of the meditations on fortitude or patience to help you calm your mind before you go to bed. Because nobody wants to go to bed angry, because you’re not going to sleep well, and you wake up angry.

You need to learn the antidotes to apply for anger. You can learn those by attending teachings and by reading books. His Holiness’ book, Healing Anger, is a good book to refer to. The idea also is to practice these techniques for subduing our anger when we’re not in the middle of a heated situation. Because that gives us some practice and familiarity with it when our mind is not completely crazy with anger. In the evening, after you do this rejoicing and purification, then dedicate the merit from the day. Then you can go to sleep very peacefully because you’ve had a full day of Dharma practice.

Each evening as you reflect on what went well and what didn’t, you’re also making determinations of how you want to act the next day. Because of this, you keep learning from your experience, and you change. So then, it becomes possible to overcome a lot of our bad habits.

Overcoming our bad habits is not going to happen by next week or next year. When we were in Copenhagen, I was talking with one nun, she and I have known each other for about forty years, and she was telling me that at the beginning of her practice, when she heard all about attaining awakening, she thought, “Yes, I’ll be able to do that in this life. That shouldn’t be too difficult. And in a few years, I’ll be able to become a buddha.” Well, it’s forty years later, and we were laughing about this, because I had that same idea, pretty much. But when we start studying, then we get an idea of all the things you must do, all the things you must change in yourself to become a buddha, and that gives you a more realistic view, and you know it’s going to take some time. So, don’t get discouraged if you’re not changing as fast as you want to. When you think that we’ve had some of these habits since beginningless time, that’s been a while. So, it’s going to take some time to reformat the hard disk, so to speak, of our mind.

One time, His Holiness the Dalai Lama was teaching, and somebody asked him, “What is the quickest and easiest way to attain full awakening?” His Holiness started to weep. When he stopped weeping, then he explained to people that that question was not the question we really should be focused on. He explained about Milarepa, and some of you may have read this story about Milarepa. When Rechungpa, his disciple, went off to meditate, Milarepa’s final message to him was to reveal his buttocks and all the callouses on his tush, on his butt, from sitting so long. The message was, “You must put some energy into this over a long period of time without expectations of quick and easy accomplishment, and with faith that if you create the causes, the effect will come.”

We need to create a big diversity of causes because our mind is a very complicated thing. One meditation only isn’t going to do it. We must enrich a lot of different qualities about ourselves. That’s going to take a while. But I think the important thing is, if we know there’s a path, and we’ve met teachers who can guide us, then, on that basis, we should be totally delighted because we’re going where we want to go. For me, just knowing that there’s a path to make my life meaningful, that gave me a tremendous amount of joy, even though I’m only taking baby steps at the beginning of the path. Think of what it was like before you met the Dharma—you had spiritual yearning, you wanted to make your life meaningful, and you looked around and were taught there’s nothing around you that is at all appealing or inspiring. Having met a path that we have confidence in, having met teachers, having the opportunity to practice—wow, this is good! The way I look at it is, however long it takes, it takes. Just creating the causes gives me more than enough to feel good about and rejoice about.

We don’t need to tap our foot and go, “Okay, when are those realizations going to come? They promised enlightenment in one lifetime. They’re not living up to their deal, I want my money back.” His Holiness calls all that talk about enlightenment in one lifetime “propaganda.” He says, “Yes, for the few individuals who have practiced for a long time in the past, enlightenment in this lifetime is possible. But for the those of us who haven’t practiced so long on the path, it’s fanciful thinking.” He says to aspire to attain full awakening in this life, but don’t be disappointed if you don’t.

This is actually quite important, because if we hold a lot of unrealistic expectations, thinking that they’re realistic expectations, then when they don’t happen, we lose our faith and we stop practicing. And in that case, then we’re really in big trouble. The real thing is about being able to practice continuously, over a long period of time. It’s like the story of the rabbit and the turtle. There’s a turtle outside the cabin where I’m staying, a good reminder—gradually walking, slowly, in the same direction.

I think there’s really a lot of reason to be very happy in our lives and very encouraged simply because we have the conditions to meet and practice the Dharma, we have a precious human life. And we shouldn’t take our precious human life for granted because we could lose some of the conditions. Because of that, we want to really make good use of our life now, while we have so many good conditions.

We can spend a lot of time complaining, we’re very good at that. “Oh, I don’t have this good condition. Oh, I have this problem. Oh, I have that problem. Oh, poor me. I can’t meditate because I have to go to work. I can’t go to Dharma class because I have to wash the dishes. I can’t go on retreat because my little toe hurts.” I’ve always thought maybe I should do a book about the 5,259,678 excuses “Why I can’t practice the Dharma.” Because there’s always some excuse. Yes? I remember one day, I had a new one: I was supposed to go teach, and I was late teaching. Why? Because there was a watermelon on the counter that fell off the counter, broke, and made a mess, so I had to clean it up. For that reason, I was late going to teach. That’s a pretty good excuse, isn’t it? Another time it was because a cat caught a mouse. That’s not so unusual, that’s already in the book. The dog ate my Dharma book. That’s the first one—when the little kids say why they didn’t do their homework: “The dog ate my homework.” So, the dog ate my Dharma book.

Instead, really see how amazingly fortunate we are. Sometimes I look at my life and go, “Wow, what in the world did I do to get the opportunity I have now?” Of course, it takes effort, energy, perseverance, and fortitude to use our opportunities, but generating those good mental factors is part of the practice. Remember yesterday when we talked about the four objects of our mindfulness. The last one was phenomena, which refers to mental factors, some of which impede our practice and some of which help our practice. Those I just mentioned of consistency, fortitude, perseverance, and so on, those fall into the mindfulness of phenomena because they help us to purify our mind. As we start to go through the four establishments of mindfulness, they will help us to generate virtuous mental qualities and help us to lessen the destructive ones.

Let’s start with prayers and remember to visualize the Buddha, surrounded by all the buddhas and bodhisattvas in front of you, and yourself surrounded by all the sentient beings.

[Chanting, prayers, and meditations].

Common way of meditation

Yesterday we had a basic introduction to the four establishments of mindfulness and talked about the four erroneous conceptions that they will help us overcome. We’re going to move into the section of the text that says the manner of meditation. Here, there’s two ways of meditation: the common way and the exclusive way. The “common way” is how we practice in common with practitioners of the fundamental vehicle who aspire to be arhats, and the “exclusive way” is how bodhisattvas practice. Within the common manner of meditation, there’s common characteristics and individual characteristics. The “common characteristics” are the things that we’re going to be aware of that are common to the body, feelings, mind, and phenomena, and the “individual characteristics” are the things that characterize

Common characteristics

The common characteristics are: impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, emptiness, and selflessness. When we look at the first of the four truths for aryas, true dukkha, these four are the characteristics of that true dukkha. I’m using the Pali/Sanskrit word, “dukkha,” instead of the translated word, “suffering,” because “suffering” is not an accurate translation. Because when we hear the word “suffering,” we think, “Ohhhhh! I’m suffering!” We think of pain, don’t we? But the Buddha wasn’t saying that everything we experience is painful. And it’s clear from our own experience that not everything is painful. But everything that we experience in one way or another is not completely satisfactory. Because we may have happiness, but the happiness is not the best kind of happiness, it doesn’t last forever. So, the Sanskrit word “dukkha” actually means, “unsatisfactory.” The first truth should be “the truth of unsatisfactory conditions,” not “the truth of suffering.” So, when you hear the word “dukkha” think “unsatisfactory.”

These four characteristics are the opposite of another set of four misconceptions that we have. One of the mistaken characteristics we have is that the body is clean, pure, and fantastic. Actually, we think everything in our samsaric life is wonderful.

If we look at our body, feelings, mind, and phenomena, they are all impermanent. Whereas sometimes we think that they’re fixed and permanent. They’re all in the nature of being unsatisfactory, even though we think that they’re pleasurable. They are all empty and selfless, and here both empty and selfless refer to “not inherently existent,” even though we see them as inherently existent.

As the text says in the next section, “All conditioned phenomena are impermanent, all polluted phenomena are unsatisfactory, all phenomena are empty and selfless.” Here, when it says, “All polluted phenomena are unsatisfactory,” polluted or contaminated means things that are under the influence of ignorance and the latencies of ignorance. Right now, that means our body, our mind, and everything around us. How is it that we took rebirth? Because our mind has this fundamental ignorance that misapprehends how things exist, then it generates afflictions, the afflictions create karma, the polluted karma, and the karma ripens in terms of our rebirth. That’s the process of how we have a polluted cause of ignorance to start with that brings about the polluted cause of our whole world and our rebirth.

Often, we don’t like to hear this. “Oh, everything in my life is polluted, it’s under the control of ignorance.” We think, “Ugh! I don’t like to hear this because I want to be happy, carefree, and do what I want! And life is wonderful, full of pleasure, and I want more pleasure!” Remember the first talk in Moscow when we talked about the eight worldly concerns? Those were all about attachment to the pleasures of this life and the accompanying aversion to the displeasures of this life.

If I were going to teach you watered-down Buddhism, I would say, “Oh, the Dharma will help you have more of the pleasurable ones and less of the unpleasurable ones. So practice Dharma, go out to the bar, have a fantastic sex life with many partners, do whatever you want, it’s fine. And meditate occasionally.” But I’m not a fan of watered-down Buddhism, what we call, “Buddhism lite”. Because Buddhism lite doesn’t cut to the chase, it doesn’t really tell us the full truth of what’s happening. It’s like saying to somebody in prison, “Oh, yes, I know, it’s problematic being in prison, but we’ll put you in a more comfortable prison.” Somebody who is rather silly may say, “Okay, that’s better.” But somebody who is smart is going to say, “Hey, it’s still prison. I want to get out of prison. I don’t care about ‘beautiful prison’ or ‘ugly prison.’ I want to get out.” “Oh, but this prison, it has such pretty colors, I like it.” That’s not really going to make you happy, is it?

In the same way, just trying to fix our samsara, or cyclic existence, just trying to make it better, there’s nothing wrong with trying to make it better, but it’s not going to solve the problem. Because the problem is that as long as our mind is under the control of ignorance, everything we do will not be real freedom and won’t give us real happiness. I think one of the things that’s so hard for us is to realize how ignorant we are because we don’t think of ourselves as ignorant people. We don’t think of our world as particularly unsatisfactory, we just see certain aspects of it as problematic. This is the ignorance that makes us live our lives according to the eight worldly concerns, and we keep getting born again and again and again and again. Each lifetime, we never find the fulfillment and true satisfaction that we want.

Facing the truth of our existence can be rather shocking at the beginning. The Buddha is helping us see that we’re ignorant, and we’re like, “Wait a minute, I’m not ignorant. Buddha, you don’t understand. I have a university education. I have a good career, I’m not ignorant.” Buddha says, “Well, that’s nice. But think about what I say and see if it applies to you or not.” That’s what we’re doing in the four establishments of mindfulness—we’re looking at things in an honest way and seeing if the Buddha’s teachings apply to us or not. And, like I always say, we must realize and understand our basic situation, because if we don’t, then we won’t be able to change it. You must see the dirt in the room in order to clean the room. Imagine saying, “I want a clean room, but I don’t want to look at the dirt. I want somebody else to clean the room.” Unfortunately, practicing Dharma is something we must do ourselves. We can’t ask somebody else to do it, we can’t hire somebody else to do it. That would be like saying, “Oh, I’m so hungry, but I’m busy. Can you eat so that I’ll be full?”

Individual characteristics

The individual characteristics refer more particularly to each of the four. Some of the characteristics that refer particularly to one of the four can also be seen in others of them, too. So, it’s not an exclusive correlation.

The first thing we’re going to think about is the uncleanliness of the body. This doesn’t mean that you didn’t take a shower. It means that our body, by its very nature, is not so gorgeous. It’s foul. This goes against how we usually think of our body. We usually think of our body as “it’s attractive and other people’s bodies are attractive.” That’s where you get all the romantic poetry—“Your eyes are like diamonds and your teeth are like pearls.” What the Buddha is adding to that is, “And your belly is full of feces.” Buddha is helping us look beyond the superficial appearance of our body into what our body is really composed of. This is going to really change the way we see our body and the way we see other people’s bodies. Don’t say I didn’t warn you. It changes our perspective in a very good way because it calms the mind and gets rid of fantasies.

The second one is the individual characteristic of feelings, that feelings have the nature of being unsatisfactory. Whether we’re happy, whether we’re unhappy, whether we’re neutral, all our feelings are under the influence of ignorance, and they don’t bring us eternal fulfillment. Whereas understanding the uncleanliness of the body and what the body is helps us understand the first truth of the aryas, which is “true dukkha.” Seeing how the feelings are unsatisfactory by nature helps us understand the second truth, which is the “truth of the cause or the origin.” Don’t get confused and say, “Well, you said the second one is the feelings have the nature of dukkha, but the first one helps you understand the truth of dukkha. Shouldn’t they correlate?” Not necessarily. Because here, with the second one, in looking at our feelings—happy, unhappy, neutral feelings—as being unsatisfactory by nature, that helps us to understand craving and how we crave for happy feelings, we crave to be rid of unhappy feelings, and we crave for neutral feelings to be maintained. That helps us understand ignorance, which helps us understand the second truth, the truth of the cause of dukkha.

The third one is to understand the impermanence of the mind. Think about how the mind goes from this object to that object; it’s always changing. That helps us to understand the emptiness of the mind, that the mind is not some kind of truly-existent “I” or person. Remember yesterday that one of the misconceptions was that the mind is the self. Seeing how the mind is changing helps us see that the mind is a dependent phenomenon, and something that’s dependent cannot truly exist. When we think in this way about the mind, about it arising and disintegrating all the time, it helps us develop a wish to attain the third truth of the aryas, “true cessation.”

What this means is that rather than always have a mind under the influence of ignorance, that’s going up and down and very moody, flitting from one object to another, completely like a crazy elephant or a wild monkey, what we want is something steady. We want to see reality, we want the elimination of all these defilements, so we’re seeking true cessation.

For the fourth one, phenomena, the individual characteristic is that the afflictive aspects, the afflictive mental factors are to be discarded or subdued, and the purified ones that are helpful on the path are to be encouraged and adopted. This helps us to understand the fourth truth, which is “true path.” It’s going to take us to true cessation.

What I suggest you do is draw yourself a little chart with these correlations:

For the body, the individual characteristic is uncleanliness, and the truth of the four truths of the aryas that it’s helping us to understand is true dukkha. For feelings, what we’re trying to understand is that they are unsatisfactory by nature, and that helps us understand true origins. For the mind, the characteristic is impermanence, and that helps us to understand true cessations. For phenomena, the characteristic is subduing the disturbing mental factors and enriching the good ones, and that helps us understand true path.

If you can keep these in mind, then you understand how the four establishments of mindfulness help us understand the four truths of the aryas. You’ll also see how this practice helps us overcome four very serious misconceptions: that the body is clean; that feelings are in the nature of pleasure; that the mind is permanent; and that phenomena form a true self. This may seem like a lot of words to you right now, but if you can put some energy into studying this and reviewing it, then as you hear more teachings, the teachings you’ll hear in the future will fill out a lot of these understandings for you.

Studying Dharma is different than studying things at school. When you go to school, you’re supposed to understand everything, remember everything, put it all on a test, and tell the teacher what they already know. When you’re learning Dharma, the methodology is a bit different. You’re taught both simple things and complex things at the same time, and nobody expects you to understand the complex things at the beginning. The idea is that hearing them plants seeds in your mindstream, and by planting those seeds and remembering those things, when you hear later teachings, you’ll begin to understand things on a deeper level.

I think some of you have been to His Holiness’ teachings in India. Did you understand everything he said? Don’t feel bad, because even some of the geshes don’t understand everything he says. The idea is that we’re planting seeds, and through continuously studying and learning more and reflecting about these things on a deeper and deeper level, then gradually understanding comes.

In the afternoon, I’ll start teaching you some of the meditations on the body. But for your meditation in this next period, reflect on these different characteristics and check your own mind. Like, do you think that your body is pure and clean? One part of you may say, “Oh, no, I know it’s made of all sorts of stuff.” But then remember how you like to dress up, look good, and look appealing, and how other people’s bodies are attractive to you. Then you realize, “Hmm, maybe I do have this misunderstanding thinking the body is pure, clean, and attractive.”

If we think that the body is so attractive, then all these old ladies and old men would look sexy. If we really think that the body is attractive, like our deluded mind thinks, then all these other people would seem sexy to us. But they don’t, do they?

Audience: Maybe there’s something wrong with me, but when I’m reading Shantideva’s description of how people are sweating and carrying feces in their bodies and that food is getting stuck in their teeth, that doesn’t . . . I don’t develop aversion; it doesn’t get me adverse.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Keep meditating. Imagine your boyfriend, what he’s going to look like when he’s ninety years old.

Audience: What’s the dividing line between nonattachment to the body or detachment from the body and active aversion to it?

VTC: With aversion, it’s like, “Ew! Ugh!” There’s this emotional thing. With nonattachment, it’s just, “I’m not interested.”

Audience: What’s the difference between emptiness and selflessness? Why do we have two points here?

VTC: In the lower schools, there’s a difference—there are different levels of the object of negation. Whereas in the Prasangika view we’re just negating true existence or inherent existence across the board.

In the lower schools, emptiness would refer to the lack of a permanent, partless, independent person, which is like the soul that Hindus and Christians believe in. For the lower schools, selfless would be the lack of a self-sufficient, substantially-existent person. That person is like a controller of the body and mind.For the Prasangikas, they define emptiness and selflessness in the same way, saying it’s the lack of true existence.

Audience: It’s a question that arose after yesterday’s discussion: when we’re talking about feelings, dividing them into pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral, isn’t that just something coming from the side of the mind and assessments of the mind? For example, “Today a cold breeze is something I like, and tomorrow it’s something I dislike.”

VTC: The feeling is one thing, but the feeling generates an emotional response. Here we’re just talking about the feeling. There might be a breeze, and today the feeling from the breeze might be pleasant because it’s really hot, and then you generate a mind of craving or attachment of, “I want this.” Tomorrow, it’s cold outside, and the breeze, or the object, is the same, but the feeling is unpleasant, a painful feeling. Then your emotional response is, “I want to get away from it.” The object is the same. The feeling responses can be different, and each feeling response has its own emotional response.

Audience: Two questions for clarification. The first one is regarding visual memory: does visual memory belong to the inner/outer body category? Or is it something else?

VTC: The memory itself is . . . you have a remembering consciousness. So, the consciousness that’s remembering is a consciousness. The object that appears to that mind is a conceptual appearance, it’s not the actual object. So, that’s an object that is just for mental consciousness. It doesn’t appear to the visual consciousness.

Audience: The second part was if you don’t remember the particular image in regard to memory, but you still remember the feeling that it caused, does that memory belong to the feeling category or is it something to do with the mind?

VTC: Again, these cannot be totally differentiated. But if you’re remembering how you felt about something, that’s the mind that is a mental consciousness—that is remembering what you felt. But if you start generating that feeling again, because of the memory, then that is the feeling.

These are good questions. What we’re getting into is the difference between directly perceiving something with one of our five sense consciousnesses and thinking about it, remembering it, knowing it through a conceptual appearance, which is done by the mental consciousness.

When it’s a direct perception, the object must be close by, because our senses are perceiving it right now. When it’s a conceptual mental consciousness, then we can put different ideas together, we can remember things in the past, we can plan things in the future. In that way, some conceptual consciousnesses can be useful. But we can also use our conceptual consciousness to worry, to get afraid, to think of how mean everybody is to us, to think of how we want to get our revenge, and all those conceptual consciousnesses are big problems.

Eventually, when we perceive ultimate truth of emptiness, we want to go beyond conceptual consciousnesses altogether. Though before realizing emptiness nonconceptually and directly, we must first understand it conceptually.

Audience: Could you explain once again what the inner body is? I understand that it’s something that receives the information. But what’s the substance or the nature of the inner body?

VTC: The way they describe the inner body in Buddhism is it’s a subtle kind of form, and it is what helps us make the connection between the object and generating a consciousness that perceives that object. It might be, I can’t tell exactly, but this is what many people say, like when we talk about the cones and rods on our retina, there’s some very subtle substance, and that might be the inner body. Whereas the whole eyeball would be part of the inner and outer body.

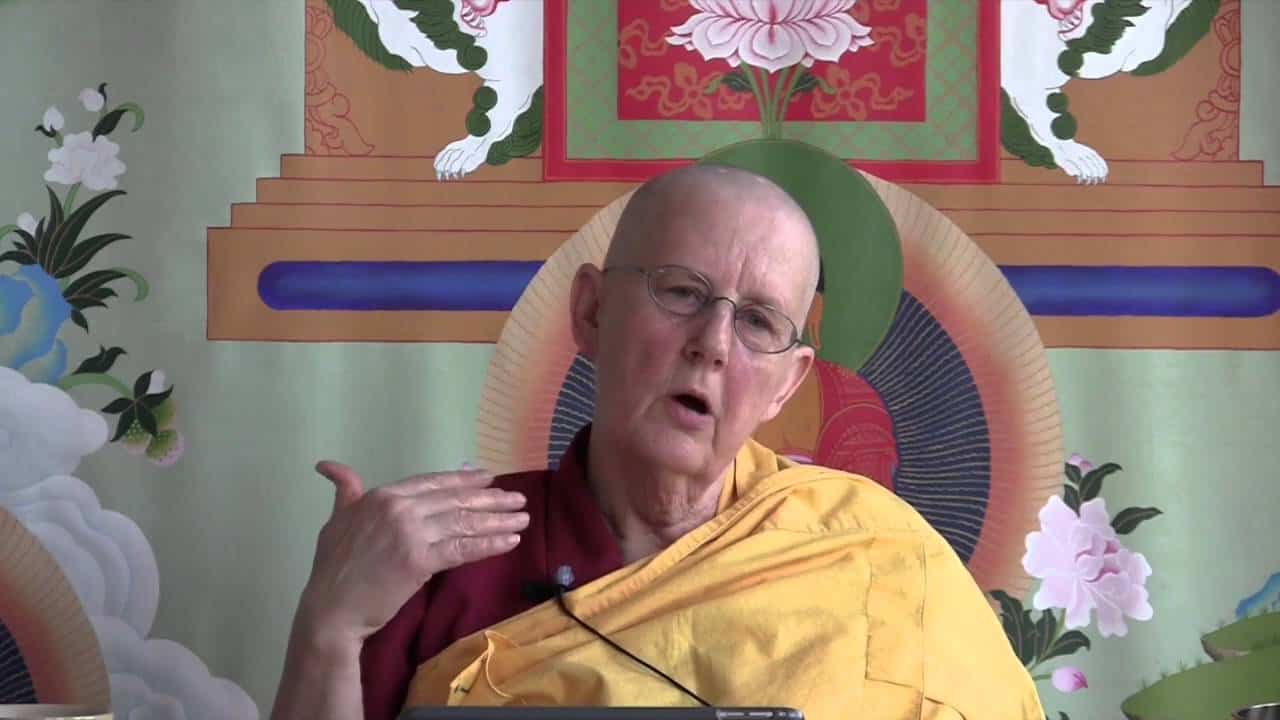

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.