Justifying our anger

Part of a series of teachings on a set of verses from the text Wisdom of the Kadam Masters.

- Overcoming resistance to applying the antidotes

- Being “taken advantage of”

- Having confidence and dignity

- Righteous indignation and compassion

Wisdom of the Kadam Masters: Justifying our anger (download)

We’ve been talking about the antidotes to the afflictions. First of all, overcoming our resistance to applying the antidotes, instead of justifying it, like, “My attachment’s good.” We didn’t talk about this one: “My anger is justified.”

What keeps us from really dealing with our anger so often is we feel it’s justified. Any normal, regular person would be upset by this. If I’m not upset, then the other person’s going to stomp all over me, and they’re going to take advantage of me. And for their own benefit they need to be stopped, because otherwise they’re going to create so much negative karma. So, out of compassion, I’m going to slam them. We justify our anger. I don’t need to apply an antidote, it’s good. I need to put this person in his place.

We can see how we do that, and how we see our anger as good.

This fear of being taken advantage of, this is really something very strong in us, this thing like, “Wow, somebody’s going to trounce me if I’m not careful.” I really see this with the guys in prison. Any slight thing somebody does becomes a big thing that you’ve got to get angry about and stand up for yourself. Otherwise they’ll just continue taking advantage of you. I try and tell the guys…. This happens in the chow line a lot: somebody comes and cuts in front of you in the chow line. Don’t wait for prison, it happens at the grocery store, it happens when you’re boarding a plane, it happens everywhere. Somebody cuts in front of you in line. People feel like, “Well I’ve got to tell them to get out of here because otherwise they’re just going to keep taking advantage of me again, and again, and again, because they’re going to see me as weak.” I tell them there’s a difference between, with dignity and self-confidence, saying, “Please come and take the place,” and, out of fear that the guy is going to beat you up, then acquiescing (so he doesn’t beat you up) and let him take the place. Instead of standing up, so he won’t beat you up, but instead he’s probably going to attack you in some other way anyway.

Are you getting what I’m saying? There’s a difference there between standing there and saying, “Yes, please, it’s fine, go ahead and do it,” and, [fearful] “Yeah, go ahead.” Out of fear. But you do it with your own dignity. Somebody does that, you don’t need to make a big deal out of it. Put the other person in front.

At airports I run into this a lot. People who think that they’re going to get where we’re going faster if they cut in front of me in the line. “That’s okay, go ahead.”

Also, when you’re driving, let the other person go ahead, rather than crash your car and get all excited with the road rage. Let the other person go ahead. It really doesn’t matter. But boy, people are like, “That’s my place, on the highway that isn’t moving.”

That’s one resistance we have to doing something with our anger, is we think that we need it: that’s it’s justified and it’s going to defend us.

Another way in which I see people not wanting to oppose their anger is similar but a little bit different. They see a situation of injustice and they think, “If I don’t get angry about it and do something, then nobody will do anything, and the injustice will continue.” So many people feel like anger is the only motivating factor we can have in order to correct injustice in the world. And I really disagree with that. You look and compassion can be something very, very strong that makes you intercede. But you intercede in a completely different way if you’re compassionate than if you’re angry.

When we’re angry, I don’t know about you, but I don’t think very clearly, and I don’t plan what I’m going to say very well, so it often comes out as a mess. Even though, the situation, somebody’s getting abused or there’s injustice, any of the social situations in the world that we feel strongly about. We can get so angry about them. But then when we act out of the anger we aren’t acting very clearly. Whereas if we have compassion—not only for the person who’s on the victim side, but compassion for the person on the perpetrator side—then we can act with some clarity of mind in a way that maybe the perpetrator can hear. Whereas if we just act with anger usually the perpetrator can’t hear it, they get defensive, they get more aggressive.

This really hit me many years ago when I was in Tibet and we had gone to Ganden Monastery—it’s up on a hill outside of Lhasa—and we were in a bus, but boy, it was hard getting up that hill in this bus. Switchbacks. Very hard getting up. And we arrive at the top. Most of Ganden was destroyed. The Chinese, and there were Tibetans who cooperated with them, they put in so much effort to get up that hill to destroy the Dharma. And I thought, “Wow, if I had put that much effort into practicing the Dharma as they put into destroying it, I would have gotten somewhere.” It really made me have compassion for these people who did this because I realized that, especially on the part of the People’s Liberation Army, it was mostly young boys in a village who wanted some work so that they could bring some funds home to the family because they were poor, so they enlisted in the army, they got sent out to Tibet where none of them wanted to be, given orders, they didn’t think about what they were doing, they just did as they were told. Certainly they created a whole lot of negative karma—I’m not justifying what they did—but when I actually thought of where they came from, and how they were raised, and how they didn’t have a clue, and the whole turmoil in China, and in Tibet during that time, then I couldn’t help but have some compassion for them.

Then if I take that into social situations that are happening today and think of having compassion for not only the Muslims that people are saying so many horrible things about, but for the people who are being so discriminatory, chief of which is (you know my favorite person) Donald Trump. But to have some compassion for him because he thinks that talking that way and thinking that way is going to bring him happiness and bring the country wellbeing. He’s not realizing what he’s doing. So to have compassion for him, and compassion for the Muslims, and with that kind of compassion speak up and say, “No, this is not the way we want our country to be. Our country is inclusive. Our country welcomes everybody, and everybody’s a citizen.” You speak up, but with compassion.

These are some of the arguments that I hear from people why they don’t want to do anything with their anger, why they think their anger is good.

So first, before we even think about applying the antidotes to the anger, we have to overcome these kinds of justifications and rationalizations in our own minds. And we find, when we’re angry, we have lots of good reasons why we should be, don’t we? Chief of which is “I’m right and they’re wrong.” Or, “They need to respect me and they’re not.” But the thing is, can we look at disrespect or injustice but with compassion, without needing to get angry about it.

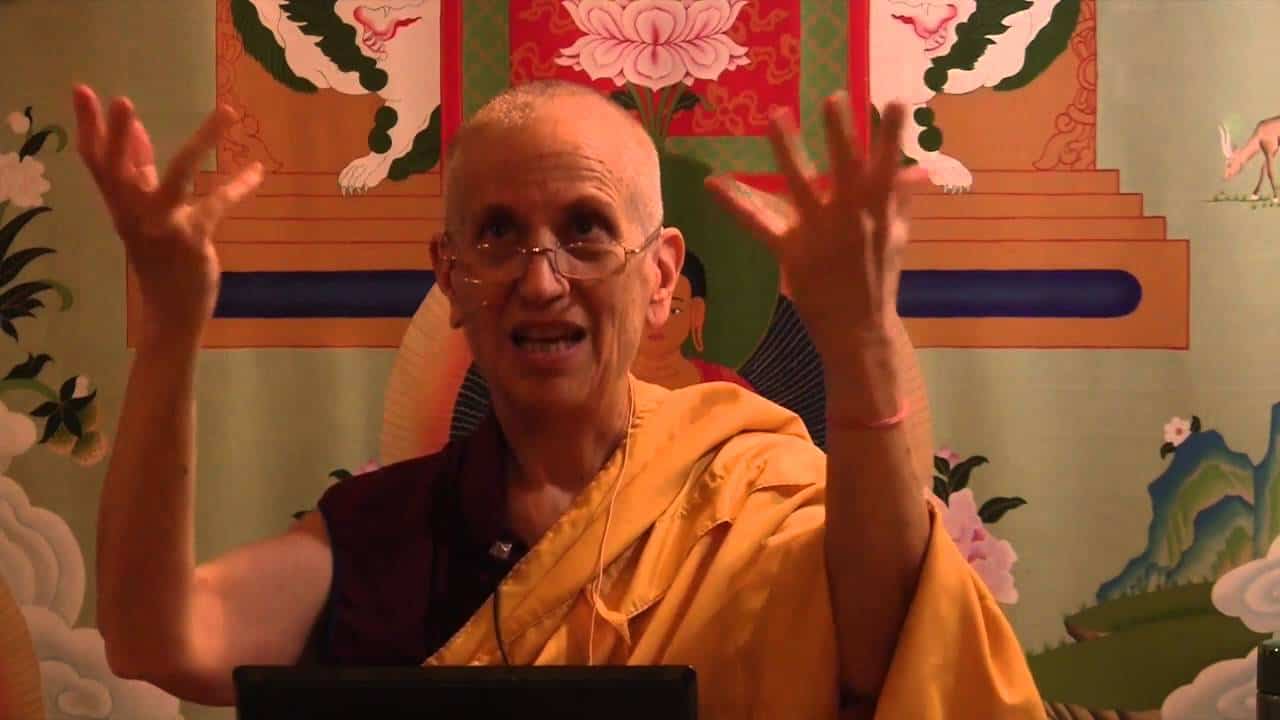

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.