Living with integrity

Living with integrity

Part of a series of teachings on the text The Essence of a Human Life: Words of Advice for Lay Practitioners by Je Rinpoche (Lama Tsongkhapa).

- Verbal pathways of action: lying

- Various types of lying

- The results of lying

- When people can’t handle hearing the truth

- Weaving around the truth on sensitive topics

The Essence of a Human Life: Living with integrity (download)

Yesterday we were talking about the 10 destructive pathways of actions, and I did the three physical ones. Today’s the four verbal ones.

The first of the those is lying. The biggest lie to abandon is about our spiritual attainments because that really cheats people in a way that completely destroys their trust in the Dharma. And also from the side of the monastics—or lay people who lie about their attainments—it’s really cheating yourself, too, and a big sign of arrogance or overestimation. That’s the big lie.

Then of course we have all the other lies. That doesn’t mean these other lies are small lies. We also tell very big other lies. They just aren’t this one that breaks the precept from the root, but they’re also quite serious.

Lying is basically distorting the truth: saying something is what it wasn’t, saying something wasn’t when it is, whatever is opposite to what is really happening. The question always comes up, “Well what about if you’re trying to save somebody’s life? If a hunter comes running up to the Abbey and says, “Where are the deer?” do you say, “Oh, I just saw one go there,” so he can go shoot the deer. I mean, of course you don’t do that. I think lying, it really has to have an element of for our own personal benefit. And it usually comes because we’re doing something we don’t want other people to know about, or we’re trying to get something that isn’t really ours, like lying in business. Deceiving in order to get a job, in order to get more money from the client, or whatever. All this kind of deception.

This whole talk may turn out about lying because there’s a lot to say about it, isn’t there?

First of all, lying destroys trust, doesn’t it? I know if people lie to me then I can’t trust them afterwards.

Ethics of lying

The New York Times has a column called “The Ethicist,” which I sometimes read because I want to see what do people think is ethical conduct nowadays. There was one letter in there from a young man who is gay who said that his father is paying for his college education, but his father suspects that he is gay (although he adamantly tells his father he isn’t, although he is), because his father—the reason he lies to his father—is because his father said that if he is gay then he will not fund his college education and will kick him out of the house and not speak to him again. So obviously it’s quite a threat, isn’t it? So this young man was asking what is ethical there. I was quite surprised at the response.

They had three different people responding. One of them said, “Well, your father is not doing his duty if he doesn’t send you to college, because that’s part of parental duty, is to support your child’s education. So if your father is threatening not to do his duty then you have every right to lie, because you deserve that college education.” The other two people said something similar—not so much about the father doing his duty, but “why does going to college have to be such a traumatic thing, just go ahead and lie to your father, and then after you finish college then tell him the truth and pay him back the money.”

I was sitting there and thinking, I’m not so sure about this kind of answer, because it promotes a culture of lying, in our own minds. And I don’t know about you people, but when I lie I don’t feel good inside. I just don’t feel good. I tried to lie when I was a kid, I was failure at it. I tried to lie to my parents. I couldn’t do it. I covered things up by not telling them things they didn’t need to know. So I just kept my privacy and didn’t tell them things that were going to upset them. But I couldn’t say purple when something was pink. And I couldn’t say “was” when it wasn’t.

I just wonder, if society starts condoning people to lie in these kinds of situations, then how do we feel about ourselves? I know it’s really difficult, especially for young people growing up. I mean I went through it too. Most of what I did I didn’t want my parents to know because it would upset them. But, like I said, I just basically didn’t go to those topics. Or changed the topic. Or wove around it in some way, so i didn’t have to say the opposite of what was.

I still didn’t feel comfortable doing that. I really wanted to be able to be straightforward and honest with my parents, and tell them everything, but when I tried that one time it was a huge failure. Essentially the message after that was, “Please don’t tell me. I don’t want to know, so don’t tell me.” And in fact my mother once told a story about something—about her friend and her friend’s daughter—and the moral of that story was, “don’t tell me.” And I saw my parents’ behavior with their parents. They lied to their parents. Because my grandmother would get very worried when we would fly to Chicago, so my mother wouldn’t tell her when we were flying. Or tell her a different day. And then we’d just arrive there. Because otherwise her mother would worry the whole time we were on the plane. So this kind of thing. It’s like my mother was doing that to save her mother the heartache, but I don’t know about you, it’s like, I don’t even want to get involved in that stuff either. Because then you’re kind of dancing all the time, walking on eggshells, trying to protect other people’s feelings, but their feelings get hurt anyway. So I don’t know.

I think definitely lying with an intention to hurt somebody, that’s something that’s quite negative. But lying to protect somebody’s feelings? I mean, I just wish people could handle the truth. Like I said, in my family the message was lie because we can’t handle the truth. So maybe in that condition it’s okay because they’re telling you to do it. [laughter] But still, it would be nicer to be able to tell the truth and have enough confidence that other people can handle the truth.

I think that’s what bothers me when people lie to me, is I consider it rather insulting, like, “What, you think I can’t handle the truth? Don’t try and protect me, I’m an adult. I can handle the truth.”

I’m just throwing some ideas out here to think about, because I know, for myself, I always feel much better when I can say, “Okay, this is just how I am, and that’s it.” Not in a way that puts it in people’s face, or rubs in the differences, or things like that, but not in a way where I’m trying to anticipate how they’re going to feel and disrespecting them because I’m thinking they can’t handle the truth.

On the other hand, when I think maybe they can’t handle the truth, then like I said, omitting different things.

It’s something to think about. And not just think about what the effect on the other person, but what’s the effect on ourselves of doing that.

Questions and answers

Audience: [inaudible]

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Right, because he’s hiding himself by not telling his parents. On the other hand, who wants to face…. I mean, he knows his parents better than I do. But if it was anything like my parents, I don’t like these kinds of blowups. So it you can avoid a blowup that would certainly be nice.

On the other hand, he may be doing it because he wants his education. But then he feels rotten inside, like you said. Even with your own parents you can’t tell them the truth.

[In response to audience] Yes. Compromising something important in himself.

[In response to audience] Yes, he’s trying to protect his relationship, which is important. But also eventually his father’s going to find out, isn’t he?

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: So being oversensitive…. Trying to go through your life protecting other people, which is being oversensitive to what you think they might feel, which is different than just being courteous to somebody. And it’s different from not putting it in their face.

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: There’s a lot of risk, and you don’t want to estrange people. But it’s also uncomfortable to keep a relationship where you can’t talk honestly. It’s really very, very difficult. I mean, my parents stopped funding me when I was age 18, because I wanted to do something they didn’t want me to do. So I said okay. And I think, actually in my case, I was better for it.

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: That’s an interesting question. If your father is funding you, thinking that you’re straight, and you’re not straight, and you’re not telling him the truth, when he said he won’t fund you if you’re gay, is that taking what isn’t freely given? Interesting question.

[In response to audience] Yes, it’s very cruel… But parents do this all the time. I mean, my parents said, “If you go to Europe with your boyfriend, that’s it.” I mean, they do this all the time.

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: So here’s another solution. Don’t tell him, but don’t take the funding either. Because in that way you’re not taking (maybe what’s not freely given). And you’re not living a lie, or lying, in order to get money. On the other hand you don’t feel ready to tell them what they’re not ready to hear yet, and you have your own integrity that you’re not selling out. Yes, that’s another way to do it. That makes a lot of sense.

These are difficult choices. But difficult choices make us grow up. If we didn’t face difficult choices we’d be infants all the time.

Lying harms trust

Then in relationships amongst adults, or even amongst parents and children…. As a kid if you see your parents lie it becomes confusing, because they’re telling you not to lie, but you’re seeing them lie. And then do I trust them? If I see my parents lie then are they telling me the truth? So it’s very confusing for kids. And also between adults it really harms trust, because…. Well, you know. I’m sure you’ve all had people lie to you.

And I think among adults, too, sometimes we do something that we don’t feel good about, and then we lie to cover it up. In that case there are two things. There’s the initial thing we did, plus the lie to cover it up. And so in that kind of situation I think it’s better to just admit what it was that we initially did, do purification practice, be honest with ourselves, purify it, let it go, and then not have to lie to ourselves or anybody else about it.

It’s really difficult when other people can’t handle the truth, isn’t it?

Weaving around the truth

Let me make one more thing. How I weave around things. A few years ago, when we first moved in here, the Mennonite church around the corner was having an open house or a fair, and we went, and I was talking to the minister’s wife and she said kind of “What’s your image of god? Do you believe in god?” And I wasn’t going to say “no” because that would stop the relationship and that wouldn’t help anything. So I didn’t answer that question. I said, “Just like you, we find that ethical conduct is really important, so we teach about not killing, not lying, things like this. And we teach about forgiveness. We teach about love and compassion. So many of our teachings and our values correspond with yours.” And she was very happy with that answer.

And what I said was completely true. I just didn’t answer her question, because I don’t think it would have been skillful to give a direct answer to that question. It would have unnecessarily harmed a relationship.

[In response to audience] If she had really pressed on? I would have said, “You know, there are a lot of different definitions of ‘god.'” And I would say, “If you see god as a holy being who has knowledge and abilities that human beings do not have, then yes, Buddhist, we believe that there are holy beings like that. We call them ‘buddhas,’ not god. If you believe that god is just the principle of love—not even a creator or anything, just the principle of love—definitely Buddhists assert that. If you think of god as a creator, then that’s where we have a little bit of a difference.” So I would put that at the very end, and left a little bit of difference, and then gone back to something that we all agree on.

I wanted to add one more point that somebody brought up. Someone said that they come from a Christian family and their nephew is gay and came out to her sister, and the sister said it made her realize how homophobic she was and how she had to change her mind. Because clearly she loved her son and didn’t want to alienate him or lose him. Somebody else remarked that this young man in the case is also in a high-risk situation because he doesn’t want to risk his education, he doesn’t want to risk his relationship with his father. On the other hand he’s sacrificing his own integrity, and he doesn’t feel good about living in a dishonest way, and that’s the kind of thing that can lead to suicide. So he’s in a difficult situation. But it’s hard. It’s like at some point you have to make your decision and be at peace with it. And if he does decide to come out, to do it and have confidence in who he is.

There are so many situations in life where you have to choose between two options you would rather not have. And so many situations where you can’t have the best thing that you want. And so the thing is to really look inside and see what is most important to us. And then go forward and accept the outcome. Because I think part of the difficulties in this situation is where we don’t want either outcome, and we’re trying to find a way not to have either outcome, which is unrealistic. In difficult situations you have to say, “Well, I’m going to have to face one outcome or the other, so which one do I want? How do I want to be? And, “I have the skills and resources and abilities to face whatever outcome it is. It may not be pleasant, but it’s also not going to last forever. And I get certain benefits from making the choice that I did.”

I think we get really messed up often when we’re trying to have a result-free decision. And result-free decisions don’t always come so easily. They don’t often exist.

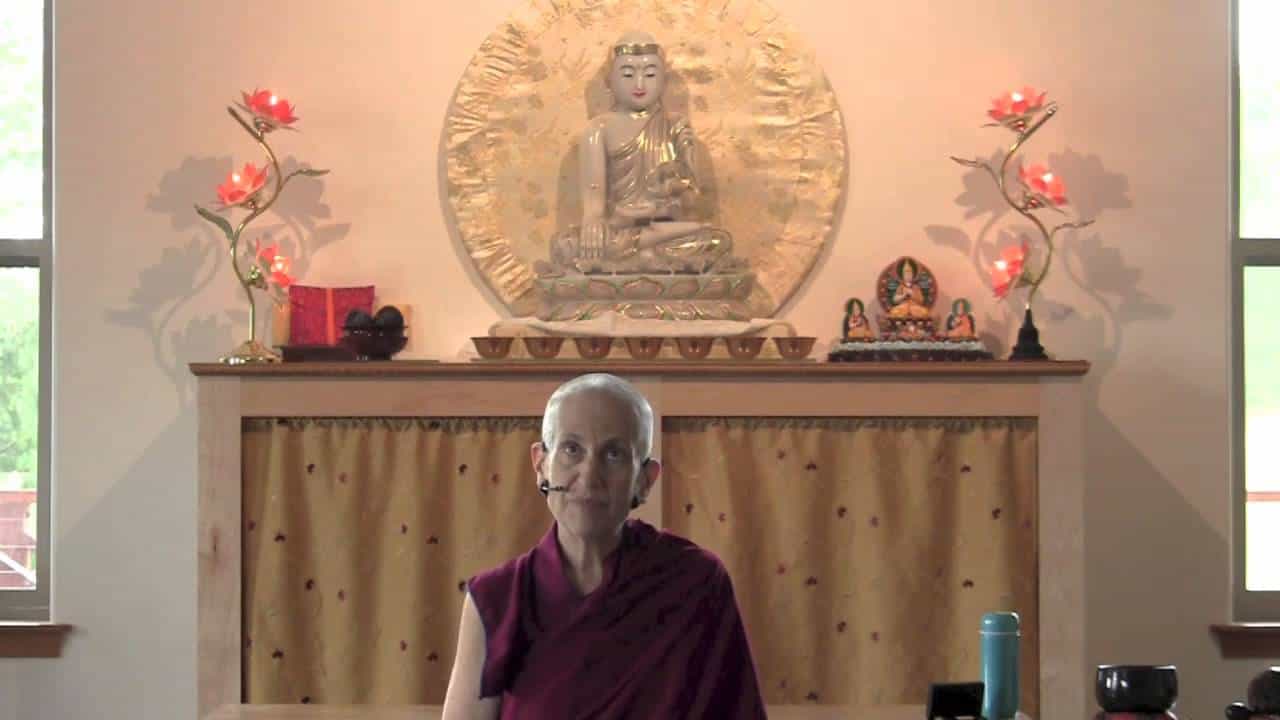

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.