Verse 73: Buddhas-to-be

Part of a series of talks on Gems of Wisdom, a poem by the Seventh Dalai Lama.

- Two ways to talk about the empty nature of our present mind

- Nothing to be removed, nothing to be added

- Giving the name of the result to the cause

- Seeing ourselves and others as potential buddhas

Gems of Wisdom: Verse 73 (download)

What is totally clean and free of every taint?

The mind that has been purified and is unmixed with the afflictions.

Actually, probably it should be “afflictions and all obscurations.” Or all defilements. Because that is the Buddha’s mind. But it’s also based on us having the buddha nature now.

Our buddha nature now has two aspects. One is the natural buddha nature, which is the emptiness of our mind. And then there’s the evolving (or transforming) buddha nature, which are all the impermanent factors that continue on until enlightenment that can be enhanced.

When we talk about the empty nature or our present mind, in one way you can say it’s pure, because it’s empty of inherent existence. In another way, because it’s the emptiness of a mind that has not yet been purified, then the emptiness itself is not yet completely pure.

But there’s this one quote about “nothing is to be removed and nothing is to be added.” And I can’t remember the other two lines, but it’s talking about…. When you talk about the empty nature of the mind, just in reference to emptiness, there’s nothing to be removed from the emptiness because the emptiness itself is not stained or polluted. There’s nothing to add to emptiness either. What we have to do is realize the emptiness of the mind, and that itself purifies the mind. And then we say by that mind being purified then the emptiness of it also becomes pure. Even though the emptiness was never really stained to start with, because emptiness is free of inherent existence. It’s not stained to start with in that way.

There’s also another analogy that they give. I think it all comes from Maitreya, about an asbestos cloth. (I know people cringe when they hear asbestos, so don’t freak out.) But an asbestos cloth which can be really dirty and filthy and full of defilements. When it’s put in a very hot fire, all the defilements burn, but the asbestos cloth doesn’t. In ancient times they called it stone wool. So they had it way back when. So the defilements would get purified, the stone wool wouldn’t change at all. So in the same way, when we meditate with wisdom, the fire of the wisdom purifies the defilements of the mind, but it leaves the nature of the mind there. So it leaves both the ultimate nature—the emptiness of the mind—and the conventional nature of the mind, its radiance (or luminosity) and quality of awareness. It leaves those things although all the defilements are burned up.

For that reason “What is totally clean and free of every taint? The mind that has been purified and is unmixed with afflictions,” and other obscurations.

We have the potential for that in us right now, that’s called the buddha nature. And then by practicing the path, that buddha nature becomes the four kayas of a buddha (the four bodies of a buddha).

So, let’s do it.

[In response to audience] So when you understand that about buddha nature, then whenever you look at a sentient being you can think, “Oh, that transmigrator is a potential buddha.” I think this relates to tantra, too, where you’re trying to see the environment as the mandala and sentient beings as deities. What you’re looking at in that case is you’re looking at their buddha nature and giving the name of the result to the cause. Which we talked about the other day. When you plant a seed you say, “I’m planting a tree.” So it’s giving the name of the result to the cause. So in this way, too. Sentient beings are potential buddhas, so you can see them as the buddhas they’re going to be. That doesn’t mean they’re not suffering now and you have no objects for love and compassion. They still are. They are objects for love and compassion. But you can also start to relate to them as potential buddhas, or as beings who have that radiant nature of the mind that is pure and the emptiness of that mind that is pure.

[In response to audience] Yes. So in Thich Nhat Hanh they say, “A lotus for you, a buddha to be,” it’s you’re practicing seeing that person in that light.

Now, you might say, “Well isn’t that just whitewashing all their faults? Shouldn’t we also notice their faults?” Well, we’re very good at noticing their faults. And a lot of their faults that we notice, they don’t have. We’re projecting those faults onto them. So, you could say it’s actually more realistic than our usual judgmental mind with which we observe other sentient beings. But you still observe that those are sentient beings who are overwhelmed by afflictions, and so they need to learn the path, they need to practice, so we still have to generate bodhicitta and complete the path. So looking at sentient beings as buddhas-to-be or deities doesn’t mean that we say, “Well, they’re all taken care of, now I don’t need to do anything for them. I can just go to sleep, and drink tea.” No.

You have to hold all these different views of sentient beings in your mind at one time, and be able to see them as sentient beings, as the deities-to-be in the mandala, as people worthy of compassion and being overwhelmed by afflictions, as people having the buddha nature and this incredible seed of purity and potential for amazing qualities. So you have to be able to hold all those different views in your mind, you know? It’s not like you say, “Oh, they’re inherently this.” Or you throw out any of the other perspectives. We have to hold all those perspectives in the same way that when we look at our body we have to hold multiple perspectives. In one way it’s the basis of our precious human life and we need it to be able to practice the path. So we see this human body as something incredibly fortunate, you know? To really protect and use on the path. Another way of looking at it, this body is just a garbage pit and there’s nothing there to be attached to. So both things are true. You know? And we have to hold both of those perspectives, and not just say, “Oh, the body’s one or the body’s the other.”

This ability to hold multiple perspectives is very important, I think, for us on the path. First of all, because it counteracts the very narrow mind that we have that wants to just label someone or something, put it in a category and then think we know everything about it. Which we often do. (You know, we often put people and things in these kinds of categories.) Actually, the fact that we can have these different perspectives is indicative of things being empty. You know? If things were not empty we could only look at them one way, they would be inherently that, there would be no possible way to see anything in any other way, and we would be stuck. So the fact that all these perspectives are valid, I think, indicates the nature of the lack of inherent existence. And so it makes our mind flexible to be able to look at things in all these different ways. Which is why it’s sometimes hard to do, because our mind is not so flexible sometimes. So this is what we often have to work with is making our mind broader so we can encompass many perspectives, many views, many different things, you know? And not just dig ourselves into a hole about anything, and say, “Oh, I’m like this, they’re like that, that’s all there is, and forget it.” Because that’s the way people wind up depressed. Isn’t it? You know, when you look at the depressed way of thinking, there’s a whole lot of grasping at true existence in there. And a lot of ordinary view. Actually, worse than ordinary view. It’s like “everything rotten. And it’s truly-existently rotten. And the situation I’m in can never change.” And that’s all erroneous ways of thinking.

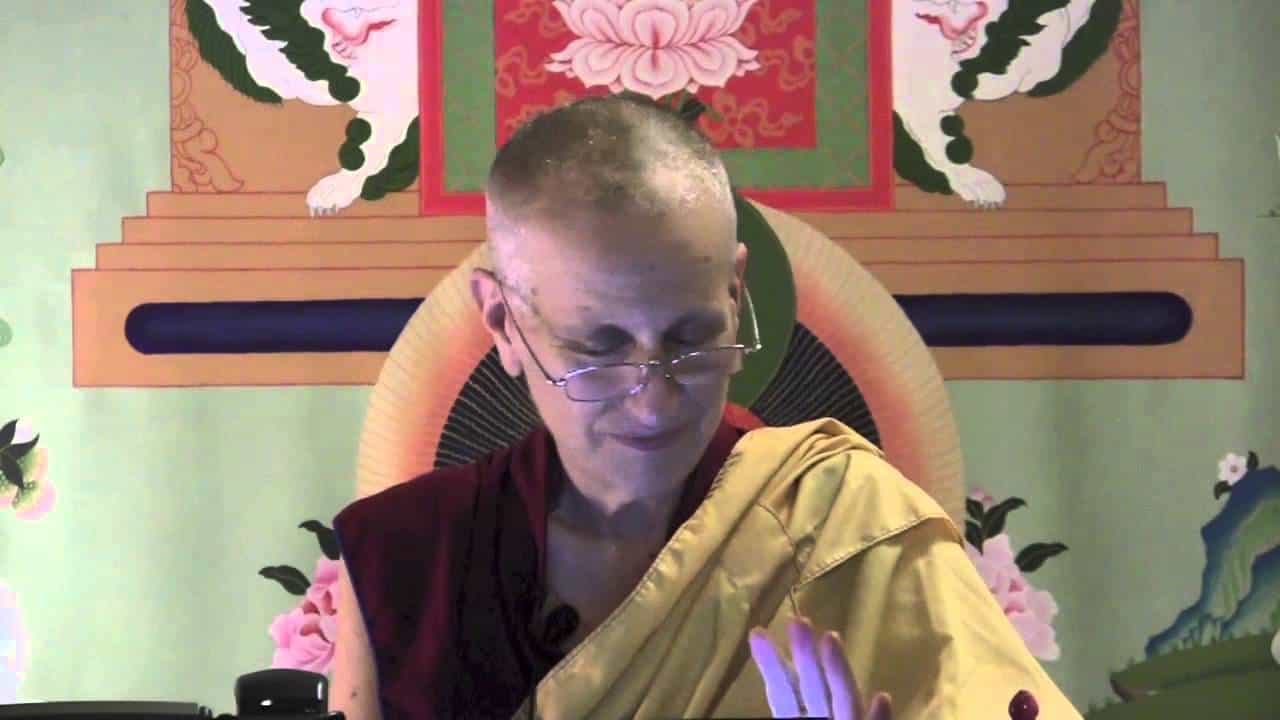

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.