Verse 56: The deadly sword

Part of a series of talks on Gems of Wisdom, a poem by the Seventh Dalai Lama.

- Denial is not something to confront with force, but to work with gently

- We need to look at our own minds and see where we deny thing and investigate wisely

- We need to develop a broad view of dependent arising and causal dependence

Gems of Wisdom: Verse 56d (download)

What deadly sword cuts off all branches of creative activity?

The sword of denial that does not face the reality of what is.

In the West we use the word “denial” in a specific way. So that is included here but it is not the only meaning. Okay? That’s very important.

Let me talk about the Western way we use the word “denial.” When we speak of somebody is not ready—well it’s the same thing—somebody is not ready to realize the reality of what is, and so they don’t want to look at it. That’s said to be a psychological technique. Sometimes people have a lot of judgment about denial. Like, “Denial is very bad. This person’s in denial. They need to change.” But I spoke with a doctor one time about denial and he said that he never tries to pull his patients out of denial because he figures if they are denying the situation it’s because they need to, they really aren’t ready to deal with it. And if you force somebody to look at something, or think about something, that they aren’t ready to deal with it’s not going to be in the least bit helpful to them. Whereas, if you’re able to create a circumstance, and help a person relax his mind to the point where they can look at something then they themselves “come out of denial.” But they do it themselves at their own time because they’ve developed whatever internal sense of well-being, or inner strength, that they need to have in order to see the situation as it is. Whereas, often in the west we think of pushing and forcing somebody out of denial. But that’s not necessarily helpful to them. Okay?

Having said that, we all need to look at ourselves and see where we tend to deny things and why we do that. Or, maybe not so much WHY we do it, but what areas do we have difficulty looking at, and what comes about because we do not look at those areas. Sometimes that’s a much better approach than, “What am I in denial about, and why am I in denial? I’ve got to get myself out of denial.” That way of relating to ourselves is not very helpful. But if it’s, “What is it hard for me to look at, and what are the effects….” You know, when we look at how NOT looking at something affects us that may give us that may give us the energy to start to look at how it affects us. Because we see the shortcomings of that. Okay? On the other hand, we may really see the advantages of doing that, because we admit to ourselves, “This is not something that I’m ready to look at right now at this very moment. I aspire to do that in the future, and these are maybe the internal qualities that I need to develop in order to do that in the future. So I will work at developing those qualities.” Yes? And so in that way give our minds some space, yes? And treat ourselves with some gentleness instead of, “I’ve got to confront this!”

Then, actually the meaning here, if we take it in more of a Buddhist sense, “What deadly sword cuts off the branches of creative activity?”

Going back to the other one: When we look at—in a psychological way—how is our creative activity limited by not looking at certain things? And so that’s one way of doing the thing of “what are the effects of not looking at things.” “How is this limiting my creative activity?” That could be another really good, useful way to look at it.

Okay, but, “What deadly sword cuts off all branches of creative activity? The sword of denial that does not face the reality of what is.”

In a Buddhist sense, the reality of “what is” refers primarily to dependent arising. So it could, in one way, refer to dependent arising as the reasoning that proves emptiness. And so thus when we cannot see emptiness—we cannot look at things as they are, and therefore develop a lot of unrealistic expectations—that limits our creative activity. Okay? That’s one way to look at it.

Or another way: By not understanding dependent arising we don’t understand causal dependence, and therefore we—in our conventional life—we develop wrong thoughts and very unrealistic expectations. Okay?

I’ll give you one example of this. Sometimes people look at the Abbey and they say, “This is all due to you.” Referring to me. And I always say, “No, it’s not all due to me.” Because it was very clear to me when the idea about the Abbey came, that one person alone cannot build a monastery. The existence of the Abbey depends upon all the people who have the karma to benefit from the Abbey. If people don’t have the karma to benefit from the Abbey, the Abbey will go out of existence. If people do have that karma, and they act on that karma, then the Abbey will grow and flourish. So it’s not one person. It depends on every single person who is involved in the Abbey in whatever big or small way they are involved. So some people are involved—they live here and it’s their 24/7 life. And somebody else may give $5 once, and that’s it. But all these people have the karma to benefit by the existence of the Abbey and to contribute to the Abbey, and all of them—each one of them—is necessary. It’s not just one person and it’s not just a small group.

It’s very important to be aware of this larger picture of how causal dependence works. That whatever we experience is a result of so many causes. I mean, so many causes, so many conditions that are happening right now. And also how we respond to what’s happening now creates new causes and goes about setting forth new conditions for what’s going to happen in the future.

There’s this whole incredible thing of interrelatedness that is really beyond our capacity to understand as ordinary beings. But just having an awareness of this helps us to have a very big mind, and to be very inclusive, and to think in the long-term. And thus, to have more realistic goals, instead of false expectations or false praise, or something like that. Okay?

And so I think that—in the example of the Abbey anyway, will help the Abbey flourish better in the long term. And then, in terms of whatever else people are involved in, that mind seeing that, you know, we are not a controller of every factor that leads to something. That so many other factors are involved that we do not have control over. And so to give ourselves some space and not expect ourselves to be able to make everything “perfect.” In other words, what we think it should be. Because the causes and conditions don’t exist for that. Because we’re all in this interdependent thing together.

[In response to audience] You’re speaking about it in terms of your field, architecture, but it could come in any field, when we say, “I’m the expert. And you shut up and do it my way. Because I’m the one who knows what’s going on here.” That when we have that attitude then we limit, actually, the creative possibilities, because everybody has something that can contribute that may be of benefit.

[In response to audience] Way back when, when somebody spoke like this, you went, “Oh, no, we’re just going to push forward.”

“All it needs is us! Not many factors, just six people.”

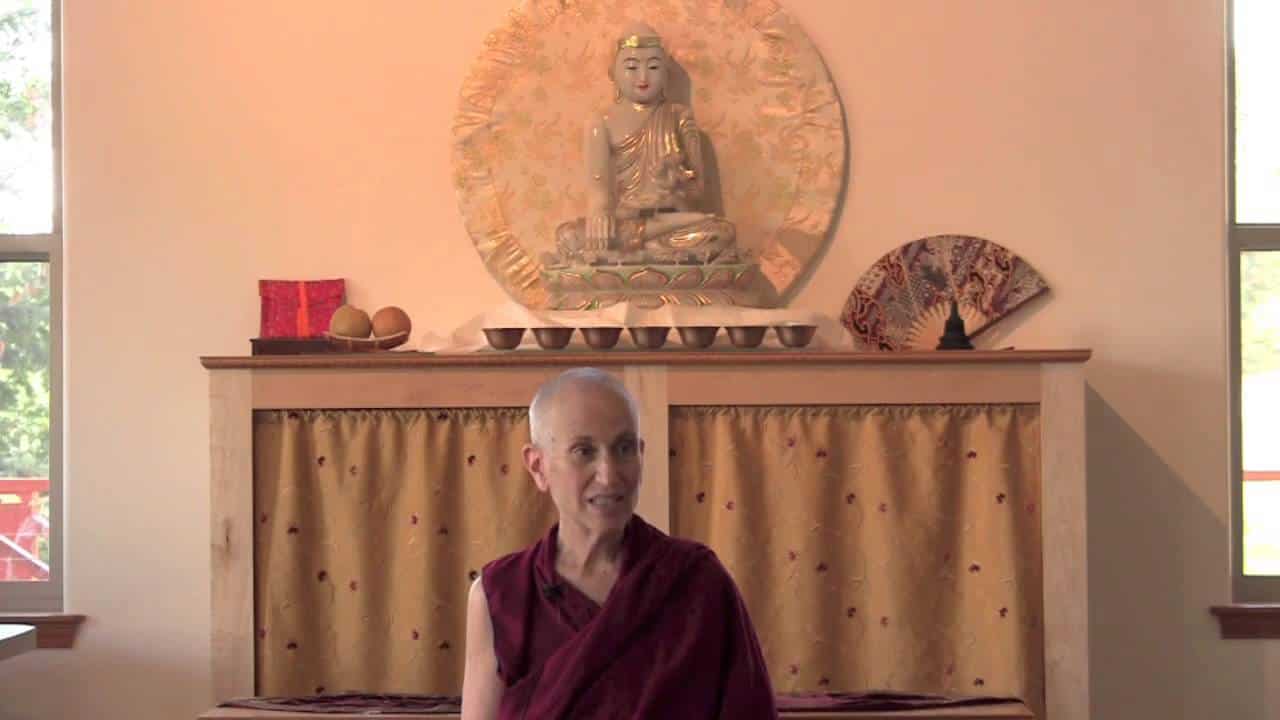

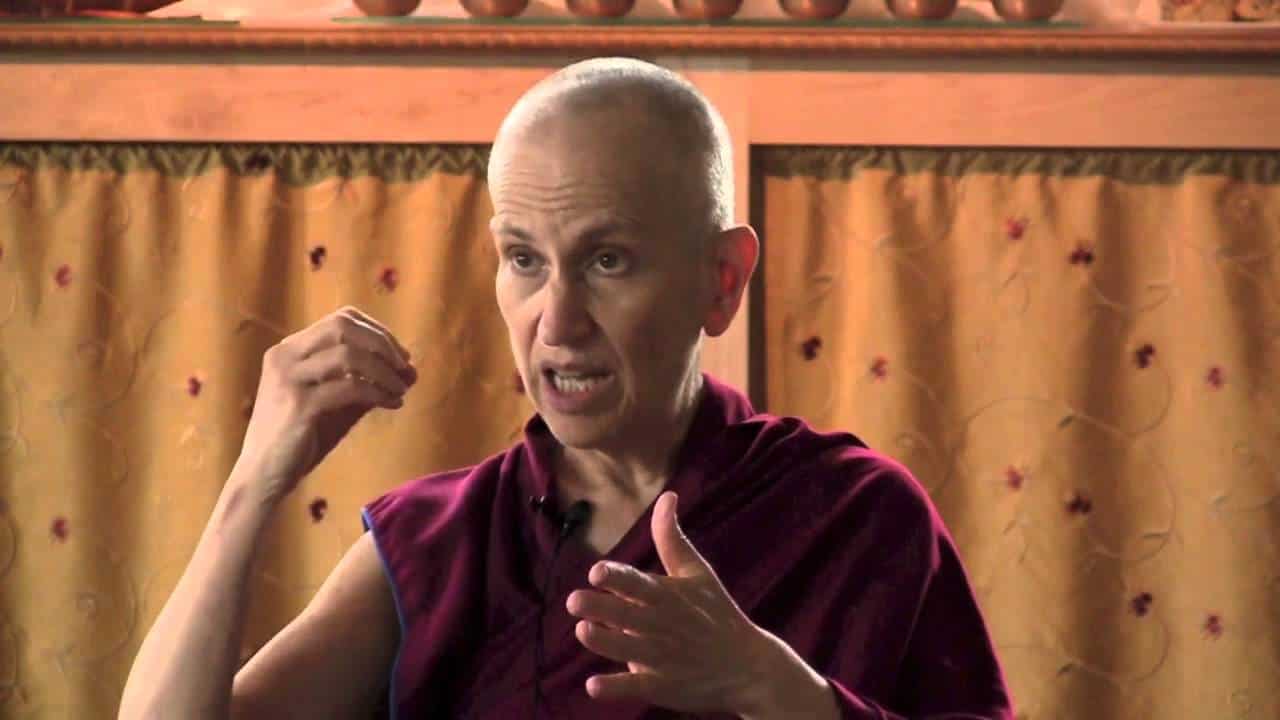

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.