Bodhisattva ethical restraints: Auxiliary vows 2-4

Part of a series of talks on the bodhisattva ethical restraints. The talks from January 3 through March 1, 2012, are concurrent with the 2011-2012 Vajrasattva Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey.

- Being disrespected (due to prejudice) and showing respect

- Auxiliary vows 1-7 are to eliminate obstacles to the far-reaching practice of generosity and obstacles to the ethical discipline of gathering virtuous actions. Abandon:

- 2. Acting out selfish thoughts of desire to gain material possessions or reputation.

- 3. Not respecting your elders (those who have taken the bodhisattva precepts before you have or who have more experience than you do).

- 4. Not answering sincerely asked questions that you are capable of answering.

NOTE: Talk starts at 5:25

Motivation

We all know we have precious human lives, that our lives are valuable, and that death comes quickly. Still, the allure of the eight worldly concerns is very strong, and at the slightest little instant it’s easy for our mind to go off chasing only the pleasures of this life. So, it’s important to reflect on our deeper Dharma motivation, to be aware of the nature of dukkha that cyclic existence has, that all these seeming pleasures aren’t going to really get us where we want to go. And then let’s remind ourselves of our true goal and steer our minds back on the path.

Let’s put our minds on our bodhicitta aspiration and really be aware of the internal joy that we feel when we know that our lives become meaningful by generating bodhicitta, and how much better that feels than the happiness that we chase after through sense pleasure and these kinds of things. Just compare Dharma happiness to worldly happiness and see where you want to go.

True happiness versus sensory pleasures

In talking about the eight worldly concerns, I’m not saying we shouldn’t have any pleasure in our life; that’s ridiculous. Of course, we all want happiness. We all want to enjoy our lives. It’s when we get attached to the pleasures of this life that we really go off base and our spiritual motivation gets ignored. It’s very easy for us to be grabbed by these little dangling carrots of temporary pleasure. We all have attachment to food—what else is new? I don’t know that that’s necessarily going to derail you from the Dharma. Of course you want to work on it, but I think we have to look at what are the attachments and aversions that have the potential to derail us from our spiritual aspiration, and especially for those who are monastics, from your monastic life.

Here we have to each look inside and ask, “What is it that I find so tempting, so enhancing, so enticing, that makes me feel so good that I’m going to run down this hill to have it?” We all have different things, but they all, in one way or another, boil down to the eight worldly concerns.

One thing that is especially prominent is relationships and the desire for relationships. This can be having an emotional relationship with somebody: “My one best friend who understands me and encourages me, who I can tell everything to.” It’s this kind of sticky emotional relationship that the world calls love and we call attachment. There’s that. And of course, there’s sexual attachment. When you put the two of those together—wow, you’re going to get down that hill real fast because “This person makes me feel so good. And, oh, um, they really make me feel good in many ways.” For people who are committed to a monastic way of life, this is the biggest one of the eight worldly concerns that derails us. Even for people keeping the five lay precepts, this can derail you from your practice, too, because you might be in a relationship, but then somebody else comes by who’s a little bit more attractive, a little bit more tantalizing, and then off you go with that new person. I’m not just talking about monastics here but lay people as well.

Of course, there’s also the desire for respect, for people to like us, to be popular, or to just to hang out and relax. “For goodness’ sake, this Dharma stuff is all the time. Can’t I relax?” As if Dharma is the cause of your stress. If Dharma is the cause of your stress I think we have to look at what are you doing in your meditations. Because if your meditation is bringing you more stress, you really need to seek some help. That doesn’t mean that we have to be in serious Dharma practice 24/7. Of course we relax, but we can relax with the Dharma mind and relax in a way whereby we’re still keeping our precepts without our mind just going off into la-la-land—surfing the web, looking at this movie, looking at that, and wanting to buy this, that, and the other thing. There are lots of ways to relax without the eight worldly Dharmas taking over.

On the other hand, you don’t want to be so uptight around the eight worldly Dharmas that you can’t do anything. I remember after I met the Dharma in the U.S. I went to Asia. Then, when I came back to the U.S., I was still a baby student, and I was so afraid. “Oh, the eight worldly Dharmas are going to completely overwhelm me. I’m going to lose my practice.” I was so tight. Don’t do that. You want to spread the Dharma, but you’re tight because you’re so afraid of your attachment. Other people look at you and go, “I don’t know that I want to practice the Dharma if that’s the outcome.” So, we have to relax, and be friendly and comfortable, too.

We’re going to continue with the auxiliary bodhisattva precepts. We talked about the first one last time: “Not making offerings with our body, speech, and mind to the Three Jewels.” This could mean any of the Three Jewels, doing something physically, doing something verbally, doing something mentally, each day.

2. Maintaining thoughts of desire/Acting out selfish thoughts of desire to gain material possessions or reputation.

Now for the second one. The second one is a doozy.

Maintaining thoughts of desire.

Or this one says:

Acting out selfish thoughts of desire to gain material possessions or reputation.

This one has the same words, but it dissects it a little bit differently. He says,

The next secondary misdeed, ‘The Great Way’ notes, has four aspects.

Here are four different ways that you could possibly transgress them.

One is strong desire. Second is dissatisfaction. Third is attachment to material acquisitions. And fourth is attachment to signs of respect. It is always, therefore, a misdeed associated with afflictions.

With some of the other ones, you can have a misdeed not associated with afflictions, because you don’t have a strong negative emotion. With this one, you always have that.

Je Tsongkhapa describes it as the ‘deterioration of the antidote to miserliness. ’ We become easily attached to our possessions, our homes, our cars, and so on. This is an example of the first aspect of the misdeed, strong desire.

He so kindly uses clinging on to material things. That’s a little bit easier for us to own, isn’t it? Strong desire for material things: “Oh yes, I have that; that’s okay.” But it could be strong desire for sexual enjoyment, strong desire for an emotionally sticky relationship, strong desire for status and things like that. It doesn’t necessarily have to be for material things. Strong desire is when the mind is stuck.

Furthermore, we are not often content with what we have and frequently wish for more or for something better, which is dissatisfaction.

That’s the old “I want more. I want better.” It comes in terms of material things. It comes in terms of relationships. It comes in so many different ways. “I want more. I want better.” This is something we have to be careful of at the Abbey, and also for people who are listening who are not at the Abbey, with all the new widgets that are available on the market. The iPad comes out, and the iPod comes out, and the iPhone comes out, and the Blackberry, and the this, and the that. All of a sudden, it’s like, “But I really need these. Everybody else has them. If I’m going to keep up with everybody else, I need them too. My old cell phone is useless. I need the new, modern up to date one so that I can really do all these extra added functions. And I’m tired of the printer I have. It’s okay, but there are so many better printers on the market—especially since it’s the Abbey’s money, it’s okay to buy it. It’s easy to get more extra widgets and doo-dads for whatever work we’re doing, because it’s not our money. It’s for the Abbey work. It’s really for the Dharma, so I really need this, and I need that, and I need this, and that, that and this, and this. I’m really so dissatisfied with the computer I have; it just doesn’t make it.” You know?

I’m not saying that we have to always work with dinosaur computers. Of course when it’s really affecting your work and you can’t get your stuff done, that’s the time to get something new, but just to watch the mind that always wants the latest this or that in the technological world. It’s so easy, because they’re always coming out with new things. “We need more. We need better.” It’s so easy. This is why we have a policy at the Abbey: For anything more than a $200 purchase, we have to come to the community. We can’t use our private money to get new blankets for our own room or new lamps or new this or new that.

Because we all need something, don’t we? “My whatever I have just isn’t good enough. And I’ll even buy it with my own money. It won’t even bother the Abbey.” No! That’s not the point. It’s important to look at this constant dissatisfaction that we have. We also need to be aware of that as a community. If we come to, as a community, feel dissatisfied with this and that and the other thing, and we don’t have enough… then we have to build Chenrezig Hall. No, that’s not it. If it were just for us, we wouldn’t build Chenrezig Hall. But it’s important to be really clear at how out-of-hand the dissatisfied mind can get. “I really need a new robe. I really need some new shoes. I really need this and that and…”

Audience: [Inaudible]

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Yes, that’s very good. Our mantra should be, “I need nothing.” Because when you don’t need anything, that’s when you have the greatest contentment. You don’t need anything, then you’re completely satisfied. But when we always need this, that, and the other thing, there is just constant dissatisfaction. That is one of the keynote features of samsara: dissatisfaction.

We long for the things that we might not often receive from others such as presents or indication of others’ respect for us, which constitute the third and fourth aspect,

So, that’s attachment to material acquisitions and attachment to signs of respect. We kind of long for these. It’s like people come to the Abbey and think, “Well, they go like this to me and see me as a senior Dharma practitioner, and think that I’m really wonderful because look, I’m wearing these clothes, and so they think of me as wonderful. If you want to give me a little bit of dana, that’s perfectly okay. You could give it to the community, too, but it’s better to give it to me.”

The desire for material acquisitions, hinting, flattering people: “Oh, that blanket that you got for the whole community is really nice! So-and-so is using it—hint, hint, hint. I could use one just like that, too.” The blankets don’t belong to us personally. They belong to the community. So, even if somebody gives you one, it goes to the community. We could get really into all these kinds of things—flattering, hinting, and making our needs known, out of dissatisfaction.

I’m not saying that we don’t have needs. It’s fine. We have needs. When you need something in your room, you come to the community. All the furniture, all these things are given by the community. We don’t go and get them on our own. We don’t hint to a lay donor to give us personally something for our room, or like that. That’s attachment to material acquisitions.

Then there’s attachment to reputation. This is what he says.

Many people complain about not being respected by others, forgetting that if they are worthy, others will naturally think highly of them! If we behave well and still people do not appreciate us, then it is their affair.

This needs some commentary. Because many of us do complain about not being respected by others. We have to look at why are we complaining. Because the word “complaining” is significant here. We’re complaining that others don’t respect us. Buddhism is new in the West. People don’t know how to behave around monastics. So, we could get into a big thing of complaining. “Oh, they don’t treat me nyah, nyah, nyah, nyah, nyah, nyah.” That’s complaining. That’s quite different than saying, “Oh, here’s a very new Dharma group. They’ve never had a sangha member come. Or they’ve never had a guest teacher. They don’t know what to do. We have to help them learn.”

Do you see the difference there? It’s very touchy. Sometimes you go somewhere, and you’re all set for people to really respect you, and do this, that, and the other, and they don’t do anything. You have to really watch your mind. Am I expecting to be treated like the Queen of Sheba because I happen to come here to teach the Dharma? We certainly shouldn’t be expecting that. If a group doesn’t know how to treat guest teachers or sangha, then we have to figure out some way so that they can get the information that they need, but without complaining to them that they’re not treating us properly.

I remember Rinpoche, when he was a little kid, talking about how people sometimes brag about their qualities so that other people will respect them. This kept getting back to the first of the root ones, but it relates here, too. He said, “It’s like if I’m a good cook, I don’t need to tell people I’m a good cook. All I need to do is cook. When they taste it, they’ll see.” When they see, then of course they respect you as a good cook. It’s the same thing. That’s what he’s saying here. If we behave well, if we do things properly, if we’re conscientious and a good practitioner, people will automatically respect us, and we don’t have to worry about that. If they don’t, then that’s their business.

It is difficult, because on the one hand, you want to teach people how to behave properly in a Dharma context. On the other hand, you don’t want to complain that they’re not treating you with enough respect. So, it’s a delicate kind of situation. It could be very easily misunderstood by other people. When I find myself in that situation, often even with you, if I don’t say something, then nobody ever learns what proper etiquette is. Then, when my teachers come here, oh boy! It just doesn’t seem right if people don’t behave properly. So, having to teach people is one thing, but we can do it without the mind that’s complaining, “You don’t treat me good enough.”

On the other hand, what about a situation where people aren’t respecting us because of their bias? Maybe their bias against our racial group, our ethnic group, our gender, our sexual orientation, our nationality, or… People can be biased over anything. So, what do you do if somebody is not respecting you because of that kind of prejudice and bias? Do you say something? Do you not say something? Is it complaining if you say something? Is it not complaining?

Audience: How would you know?

(VTC): How would you know? You could tell by the comments people make, how they react to you upon the first time they meet you, or how they react to everybody from your own particular religious or racial or gender group, or things like that.

Audience: I would think it really depends on context, because if you’re in an airport and someone stares mean at you and says something, but you’re just passing by, you’re probably in your mind just going to wish them well and say, “Wow, that’s my karma ripening,” for them treating you in that way. But if there’s a relationship where you’re going to be there for a while, then I think that it needs to be addressed in some way, maybe as a kind of NVC, checking with yourself first, and with others around the situation, where the person got all that.

(VTC): You’re saying it depends very much on the situation. If it’s a small thing with a stranger, maybe you just wish them well and disregard it. But if it’s something where you’re going to be somewhere for a long time and have a lot of contact, then you may want to address it and talk with other people in the situation about it. I agree with what you’re saying. In both situations, we have to be aware of the mind that complains.

Audience: It won’t work.

(VTC): Yes, it won’t work if we’re complaining—not at all.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): You’re saying even if it is some kind of group prejudice on the part of the other person, you don’t have to let it get to you.

Audience: I don’t have to answer back in the same way.

(VTC): Right, you don’t have to respond in the same way that that person acted towards you.

Audience: Or in any way maybe.

(VTC): Yes. It seems to me, if the person’s bias, let’s say, is going to deny you an opportunity to learn something that you want to learn, or an opportunity to use your creative capacity that benefits others, or you’re denied some kind of possibility that would really enhance your life and your ability to be of benefit, then it would be good to address it, but in a skillful way. If it’s a personal affront, and we’re just really prickly over personal affronts, then we really have to look at that mind that loves to take things personally.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes. She’s referring to a story I told how at the teachings with His Holiness one time, I noticed the monks always stood up and got to offer the tsog to His Holiness, and I would sit there going, “Oh, the monks always get to do it, and we women always have to sit down, and they get the opportunity, and they pass out the tsog, and they do this and this. ” But then I realized that if the women were the ones doing it, then I would say, “Oh, look, we women always have to get up and offer and distribute the tsog, and do this and this, and the men just sit there.” So, I realized it was coming from my mind, the thing that was complaining so much.

So, what do you think of what he says—that if we behave well and still people do not appreciate us, then it is their affair? Do you really believe that?

Audience: I believe that it would be great if I really did believe that.

(VTC): You believe that it would be great if you really did believe that. If we look closely, that’s true, isn’t it? It would be wonderful if we really could think that—that that’s just their affair. But do we really think, “Oh, they don’t respect me, they don’t honor me, they don’t do this and that for me, that’s their affair?” No. We think, “How dare they treat me like that. They don’t have any manners, their bias, their prejudice, their this, their that. I have every right to jump on them and complain.” It is something to really bring up in our meditation and practice this thing of “this is really their affair.” And “why is it their affair and not our affair?” It’s because our mind can think of so many reasons why it’s our affair. “If they don’t respect me, then other people are going to see it, and then the other people aren’t going to respect me.” We have all sorts of reasons, don’t we? “If they don’t respect me, then I won’t get my fair share, and I have to get my fair share, because everything has to be fair.”

Audience: But I’m thinking about, like the civil rights movement. It’s not just their affair if they disrespect, discriminate. And if I just say, “Oh, that’s their affair,” then who would have sat down at the lunch counters, you know? So, it’s this tricky thing of the personal part getting all tangled up in the self-centeredness, but there is an aspect if you want justice that’s really important to stand up for.

(VTC): Okay, so there’s this ambiguous area, and I think the civil rights movement is a very good example. Where do you just take people’s prejudice, and say, “Well, that’s their affair,” and go sit in the back of the bus, sit in your corner, and where do you bring it up as an issue?

Audience: I think it’s a certain motivation thing—personal versus group.

(VTC): Yes, a lot has to do with whether it’s you’re feeling personally offended and it’s me, or whether you feel like you are representative of a group and working on behalf of the group to establish something fair for the entire group.

Audience: I still think it’s none of our affair. If you want to do it because you want respect, that’s the craving problem. I can look and say, “Oh, they don’t respect me. That’s none of their business. I’m going to sit at this counter anyway.” Just because you accept that it is their affair doesn’t mean that you then slink away. It means that you actually have more power to stand up and not be touched by other people’s opinion; it really is quite empowering.

(VTC): What you’re saying is, if in those situations where you’re experiencing prejudice, if you really say, “It is their affair, and so because it’s their affair, I’m going to sit here anyway,” then you actually feel more empowered.

Audience: I was thinking about in nursing versus doctors in the workplace. As a group it seemed like we needed to raise our own esteem and feel like we were competent. Once that seemed to be strong and healthy, then that’s when we could stand up, maybe not our affair, but still we would do what needed to be done regardless of how they were treating us. That changed the situation; it changed how they saw us.

(VTC): You’re saying in terms of a group that’s being discriminated against, and you’re using the example of nurses relating to doctors in a hospital, that when the nurses had more self-esteem and more of a feeling of their own capabilities, they did what needed to be done without slinking away. And sometimes, you can do what needs to be done without raising a big ruckus. Standing up for what needs to be stood up for doesn’t mean that you have to criticize the other person and threaten them and make a scene, because that usually turns them against you. It’s an interesting one of really looking at what our motivation is, but I like very much what you said, if I really truly believe that is their affair, then I don’t let the limits they’re putting on me be limits for myself, because I realize that is their affair, and so I can go through, beyond those limits.

We make this misdeed when a strong feeling of attachment of any of the above kinds arises in our mind and we go along with it; we do nothing to counteract the disturbing thought, such as apply its remedy. The fault is letting the antidote to miserliness deteriorate. Miserliness’ antidote is the wish to give, and yielding to any of the four kinds of attachment is clearly incompatible with this wish. Being very attached to our belongings is inconsistent with the desire to share them with others.

So, that was the first one.

The second one is:

Furthermore, being dissatisfied with what we have and wanting more, as well as longing for gifts or honors.

That’s the third and fourth one.

These are not in keeping with generosity, the remedy to stinginess.

The idea is that when we’re always full of desire and wanting, wanting, wanting, it impedes our ability to give. That’s quite clear, isn’t it? Because stinginess is like, you have something, and you can’t give it. This is so much desire. Let alone have something that you can’t give, you’re actively looking for something for yourself.

When attachment and discontent arise in our mind, we may not succeed in countering them immediately. They may be so powerful that they overwhelm us for some time despite our efforts to recall their drawbacks and the advantages of non-attachment and contentment. If we sincerely want to put a stop to them, strive to do so, apply their antidotes, but because our afflictions are particularly strong, we do not succeed, we do not commit a secondary misdeed.

If you really see that your mind is overwhelmed by attachment, you try applying the antidote, but the afflictions are just too strong, and you get carried away, then you don’t break this one because you tried. The transgression happens when the attachment is there, and we just go along with it without trying to oppose it in any way.

We have tried our best and done what we could. This does not mean however that we are blameless and that our feelings of attachment carry no negative effects. It is simply that they do not amount to a secondary misdeed of the bodhisattva ethical restraints.

So, you’re not karma-free, but you’re not breaking the precept.

We can see that bodhisattva practice is both logical and psychological. Its purpose is to help us improve our thinking. When an affliction like attachment or discontent overpowers us, if we earnestly endeavor to stop it, then we are acting in accordance with bodhisattva training. Our application is correct because we are sincerely trying to improve ourselves. Logically, making no effort and just surrendering is a misdeed because we are doing nothing to progress, which goes against the purpose of bodhisattva training.

So, when we’re trying to do what we can, we’re not transgressing. But when we just say, “Oh, whatever, that looks so good, let’s go after it,” without trying to apply the antidote, then that’s when we get in trouble.

3. Not showing respect to seniors.

Number three, also from Chandragomin, is:

The third misdeed, not respecting seniors, is contrary to generosity in the form of giving protection and fearlessness.

It seems funny; why is not showing respect counter to giving protection or fearlessness? Nobody directly suffers if I don’t show respect. But we suffer when we don’t show respect. Also, when we show the example to other people of not showing respect, it could cause suffering.

Its objects are seniors, which in this context are people who have taken the bodhisattva vow before us and have therefore been observing them for a longer period of time than we have. It is not a matter of age, but of the length of time that a person has trained in bodhisattva ethical conduct.

Our seniors, here specifically, are those who have taken the bodhisattva precepts before we have.

Moreover, here the term senior refers to people who have certain good qualities, either scriptural knowledge or scriptural realizations, which make them trustworthy.

Somebody might be a junior, in terms of how long they’ve kept the bodhisattva vow, but they have many good qualities. Then they’re still considered seniors.

Although the seniors in question are not immediately put in danger by our lack of respect for them, on our part the misdeed still conflicts with the gift of protection. As for the action, there are various ways in which we can fail to show respect. We may refuse to rise, although it is common practice in society to get up when some worthy person enters the room.

I remember being raised like that—when somebody elder comes in the room, or somebody who does something respectable, you stand up. I’ve noticed that now, young people don’t do that at all. We have young people coming to the Abbey, and somebody who is senior or their teacher or somebody walks in, and they just sit there and keep eating, keep chatting. There’s no idea of this. It’s quite amazing what’s happened in the space of one generation. Sometimes I wonder what has caused this. Is it just kids being pampered, or is it that our notion of equality has taken over so much that we feel that showing respect to any other person is unfair because it makes ourselves less than somebody else? That’s really quite a foolish way of thinking. I don’t want to be equal to the people who are better than me. I want to show respect to the people who are better than me. I don’t want to consider myself equal and just as privileged, as entitled as them—because I’m not.

We may fail to greet people and offer them a place to sit.

That’s another way of disrespecting.

We may also be impolite in the way that we address them.

We might say, “Hey, you,” or call them by their first name, or we might not use a title or something like that when we should. Or we may be impolite in the way we ask them questions, thinking that they’re just there to answer our questions, or asking them questions that aren’t really suitable for us to ask them.

Behaving in any of these ways with someone who has trained in the bodhisattva practice longer than we have is a misdeed.

This is something to be careful of, because sometimes it’s just like, “Whatever. We’re all equal. I’m busy. This is no big thing.” You have to see what your relationship with it is, with somebody. I remember when I first went to Kopan, I was taught that every time Lama came by, we should stand up. I remember situations where I was trying to teach the boys English. Lama would come to listen, and I would disrupt the class and stand up and say hello to Lama. He’s all the time saying, “Sit down and continue.” In that kind of situation, I should sit down and continue, because he wanted to see how the boys were doing in learning English, and he didn’t want the class disrupted by me doing that.

So, you have to see what the situation is, what the person has told you before. With some of my teachers, I have much more informal situations. Other relationships, with my other teachers, they really like the relationship to be more formal. And even with some of them where it’s more informal, in some situations I’m very formal with them because that’s what the situation calls for. So, you really have to see what the situation is, who else is around, how that person asked you to act, and deal with it situation by situation.

Audience: I knew a person that used to be a monk, and he disrobed. He did a lot of Dharma and everything, and he just got re-ordained last year. I have more seniority than him. How do you deal with that?

(VTC): It’s a situation where there was somebody who was a monk before. He developed a lot of knowledge and so on. Then he disrobed. You got ordained in the meantime, and then he just re-ordained a year ago. You’re senior to him in terms of monastic ordination, or maybe even your bodhisattva vows, but you regard this person as somebody who has more good qualities than you do. You have to see what the situation is. If it’s a monastic situation where you’re going strictly by seniority, then you follow that. If it’s a private situation where you want to show respect to somebody that you respect, then you show them respect.

For example, there are different points of etiquette. I’m going off on a little bit of a tangent here. If you’re around your teacher and your teacher’s teacher, then you don’t show great respect to your teacher; you show respect to their teacher. For example, at Deer Park, Geshe Sopa would be teaching, and Lama Zopa would be there. Some people would kind of wait for Lama Zopa to sit down and would stand up when he came in, even though Geshe Sopa was already there. You don’t do that. When you’re with your teacher’s teacher, your teacher’s teacher is the one that is the focus of your respect. Your teacher, of course you treat them politely and courteously, but you don’t do things to show undue respect in the presence of their teacher. On the other hand, you don’t just treat them like Joe Blow either.

And then there’s things like if you have a lay teacher and when a lay teacher has come to teach. Monastics are not allowed to bow to lay people, because we have a higher ordination. But if somebody is your teacher, you want to show them respect. So then you stand in front of a Buddha image that might be near them and bow to the Buddha image—something like that.

4. Not answering questions.

The fourth misdeed also conflicts with generosity in the form of giving protection. It consists of not answering simple questions, such as, ‘How are you?’ or ‘How is your health these days?’ when they are asked in a sincere and friendly way. Or it may be that we do respond but in a sharp or aggressive manner. An example would be to angrily answer someone who asks after our health with ‘Mind your own business!’

Sometimes, maybe your health isn’t so good, but you don’t really want to talk about it with everybody, so then you just say, “Thank you for asking,” or “I’m doing as well as I can.” You respond in some way. You don’t turn away from them and just say, “Shut up. It’s none of your business.”

In either case we fail to respond to their expectations. It is a misdeed whether the person asking the question has the bodhisattva vows or not. In fact, this fault concerns everyone, whereas the previous misdeed has a specific object.

In the previous one, the object was somebody who has the bodhisattva vow before us. In this one, it’s anybody—somebody who just asks us a general question.

It is important that we give clear and polite answers to questions that we are asked, unless there is a good reason for not doing so.

Here it’s kind of referring more to just general manners. Maybe it’s not even in terms of a person asking you a question; the person saying “hello,” and you just walk them by without greeting them. It could be that. I would think it could apply to that thing, too, not just a person asking you a friendly question.

Many of the secondary precepts of the bodhisattva ethical conduct are in keeping with the standards of good behavior in society. By simply complying with these in situations that we encounter every day of our lives we will easily be able to observe a large number of the precepts and avoid misdeeds.

He’s saying if you just behave like a mensch. A mensch is like a nice, warmhearted individual—a warmhearted, humble, friendly individual. Then you’re going to save yourself a lot of transgressions. What happens when we’re angry? When we just walk by people without answering? When we’re proud, and we don’t want to show them respect? Or we’re greedy and we’re trying to get to something before somebody else does? That’s when a lot of our manners really decline.

It seems like nowadays maybe we have to teach a lot of people manners.

Audience: Yes. I actually asked about this with respecting our elders. It just seems, like you said, that it’s not really present in this generation, and it seems like our culture has become so casual that you can almost feel even awkward sometimes to show respect, that showing it would help me to feel it more. So, I’m curious how to show respect in certain contexts.

(VTC): Yes, it’s a very good point. So, this is a twenty-something speaking, saying that you feel like you really want to learn more about how to behave in different situations, and that society has become so casual that sometimes you want to show respect but you feel awkward in doing so, like other people are going to look at you like, “What are you doing?” or whatever. But you know that it would actually help you to do that. I would say go ahead and do it, and it might really set a good example for some other people. And if they ask you, “Why did you stand up for that person?” then you can explain to them about the benefits of noticing other’s good qualities, and respecting them, and how that helps us to develop our own good qualities. So especially people of your age, if they notice you doing that, and then comment on it to you, it’s an opportunity for you to share something.

Audience: A new development like “manners schools.” I don’t know what to call it—“good behavior schools?” It’s like a kind of university where you go and you learn like in a normal school, but then you also learn how to behave. I don’t know what you call it, but…

(VTC): There are whole schools for teaching you how to behave. They had that when I was young—debutants and all this kind of stuff. They called it “Finishing school.” But I think it doesn’t hurt to learn some manners. Just basic human manners sometimes can save us from so many disputes and misunderstandings with people. Because sometimes it’s just because of a lack of plain old acknowledging someone’s presence, or acknowledging what they did, or just very simple things that people get so hurt and offended by. It’s important.

Audience: I think it’s just young people anymore. I think they’re kind of out of the habit, even if they learn. I was just last year in a situation where I was with a group of Buddhists actually, and a monk came, both an elderly man and a monk that we didn’t know. But A, the monk, and B, who was quite elderly, and nobody moved. I did, but I was raised in the south. But it surprised me that just from the very fact, forget the monk part, just the very fact of an aged person who is a stranger to the group was not welcomed in a more respectful way. And this is among people my age, so…

(VTC): You’re saying even people in their ‘50’s and so on… There’s a situation with a group of Buddhists, of course, who were working for the benefit of all sentient beings, but an elderly monk came, and nobody moved. There was another monk, and he did, and you did, but then all the other people sat there. You’re saying, aside from it being the fact that he’s a monk, which would make him an object of respect, the fact that he’s old should make him an object of respect also. And to at least show consideration for somebody who is older.

Audience: And the quick deduction that he probably is quite the senior monk.

(VTC): Yes. That could be an Abbott and who knows what, but we don’t know him and “We’re all equal.”

Audience: I think sometimes the respect that someone shows could be misinterpreted as submission. Like if I want to show respect to someone, that someone won’t accept it because they would think that I am thinking like I am under them. But it’s just a sign of respect.

(VTC): You’re saying that sometimes showing respect can be a sign of submission to somebody?

Audience: Mostly in the cities, when someone from the countryside comes and shows some kind of respect, the people from the city say, “Hey, no, come on, sit down, you’re equal to them.” So, it’s misinterpreted. I want to respect them, and I show it, but they want to refrain from doing it, because they are interpreting it as submission. And so, it is to show respect for the people.

(VTC): You’re giving an example of somebody from the countryside coming in and showing respect to somebody who lives in the city. The person who lives in the city misinterprets that as that person is thinking that they’re lower than me, and I don’t want them to think that I want them to think that everybody’s equal. But in fact, the person from the country is just showing respect.

Audience: So, it starts to stop showing respect because…

(VTC): Okay, so then that person would stop showing respect. But then, why would the person from the countryside show respect to the person in the city?

Audience: Not because that person is from the city, perhaps it’s some of more age or because he respects the other person and just wants to…

(VTC): Oh, okay, so it’s no necessarily because they’re from the city.

Audience: It’s just one respecting the other.

(VTC): Okay, one person respecting, the other misinterpreting it as they’re making themselves lower, where they want everybody to be equal, so then the person stops doing it.

Audience: In the city, I think they are losing their respect, and in the country the people are more familiar with respect. When they go to a restaurant, the people in Oaxaca will always say good afternoon. In the city, when you say something like that because you are familiar, it is customary when in the country to say “good afternoon” when you finish. You say, it’s a Mexican custom. You are leaving, and you say something to show respect. But, when you go into the city and say these things, the people are like, “Something is wrong with you, you look very strange.”

(VTC): This is kind of like the situation John is talking about where you’re showing respect, and you’re showing common courtesy to somebody, but the people in the city, or the people who are around you as young people say, “What are you acting that way for?” And so, then you think, “Oh, well, I want to fit in with everybody else,” so then you stop doing it. But actually, it’s a nice kind of thing to do, like you’re saying when you go into a restaurant to greet the people and before you leave to thank them and…

Audience: I don’t know how to say when you finish, too, you say “provecho.”

(VTC): Enjoy, good appetit.

Audience: In Mexico in the big cities, they lose all this respect.

(VTC): So, signs of respect or just plain old common courtesy, people really, they’re too busy; they’re too stressed. They’re too self-centered. I think that’s something that we should really do our best to embody—to do those small things, especially when we go out in public, to extend those small courtesies and kindnesses to other people. Some people look at you like you’re strange for acting that way, but other people may look at you like you’re strange, but they notice it and they respect it themselves. And they actually feel better around you, because you say hello to them whereas all these other people don’t.

Audience: I do remember sometimes feeling, when somebody was paying me respect, it touched my heart, it did.

(VTC): Oh, yes. Sometimes when people show you respect, it really makes you want to behave better. It really touches you. When I go to Singapore, after the teachings very often people come up and they want to make an offering. Just the way they make an offering and how they greet you, or how they bow, it really makes you feel like, “Oh, I want to behave well and be a proper monastic.” You feel the way people are respecting the role that you’re in. It can really make people rise up to the occasion when we respect them.

Audience: I’m thinking about the twenty-somethings, thirty-somethings—how we were raised and being a parent. When I raised my son, we did not emphasize this kind of manners and such because we’d gone through this leveling process of the 60’s where everything was literally leveled. What became the focus was equality, and children should be respected, and children have rights. I remember that was very much in the culture: children have rights, children should be respected. So, it was this different focus, and I remember when he was about six, looking at him and going, “Wow! He doesn’t have any manners.” And I remember my brother being really upset with me. When we went to visit my brother was about, “Why haven’t you taught your kid any manners?” So, I had to really sit and talk with my son about, “Stand up when your uncle comes in the room,” and he was like, “Why?” It was like, “Wow! This is interesting,” because we had kind of taken it all out.

(VTC): You’re saying the generation that grew up in the 60’s and 70’s made everything equal: kids have rights, and kids should be respected, and so as a result, the kids never learned any manners, and it could be upsetting to other people later on. And then actually, now as you’re a parent, and you watch how your son treats you, you wish that he had more manners and more consideration, don’t you?

Audience: Basic polite respect.

(VTC): Basic polite respect and consideration, but your value in raising him when he was little was, “We’re all equal, and I want him to be my friend.”

Audience: When I was teaching, I noticed this a lot in families. One thing that really stood out was that I could see that people had no time to speak to their kids. Everyone was racing to the next thing. For anyone like John’s age or older, for younger ones, to learn these things, your parents have to sit down and take time with you. There was one statistic that I heard when I was teaching fifteen years ago, that the average time that a parent spent talking one-on-one with their child, in a week, in a good week, was eleven minutes.

(VTC): Oh, my goodness!

Audience: Eleven minutes, and that was in one week. Everyone is sort of shuffled here and shuffled there. You have to be taught these things. You have to model them; that’s how they learn. So, it’s mostly this generation of not being taught.

(VTC): Yes. Okay, so you’re saying as a teacher, watching, and parents not teaching their kids manners because they’re so busy doing this and that and the other thing, taking their kids here and there, and that you remember reading that the average amount of time that a parent had talked one-on-one with their child in a week was eleven minutes, which is shocking. Because to learn manners, and respect, and proper attitudes, children have to be instructed verbally, and it also has to be modeled. But when everybody is in such a hurry going here and there and the other place, it doesn’t happen.

Audience: I was going to say that I’m part of the generation that did not learn these “rise when your elders come in” things, but also that, and I’m not disagreeing with a lot of things that have been said, but also in my family people knew that I respected them without those things happening. So, at the same time for people who are not seeing this happen I think it’s good enough to assume that the person had more respect or manners, and simply that it wasn’t done that way in their family. My parents knew that I respected them because I listened to what they said. I followed their advice. It was a different kind of relationship—at least from our side. I’m not disagreeing with anything that’s been said, but in certain situations there are ways to act, and I agree with that. I like protocol, but that’s from our side. I’ve dealt with this in the college system because, even from my generation to the students going to college now, there are differences. I’ve had to really communicate a lot with different people to understand that. Just because they didn’t act the same way it didn’t mean there was no respect.

(VTC): You’re saying that just because people don’t show formal respect doesn’t mean that they don’t have any respect at all. So, don’t be too quick to jump on them. That’s very true. But like you said, in your family, maybe you didn’t have to rise and these kinds of things, but you listened to your parents’ advice and things like that. What I observe sometimes, too, is some people still may have respect and listen to advice, but some people, let alone the external manifestations of respect, the internal ones they also lack. I mean somebody may not rise, but then if they just sit there and they’re casually talking and completely ignoring, that’s different than if they don’t rise but they nod their head and greet you. So, there’s different levels, different ways, of showing respect.

Audience: I only wanted to say, how do you know that somebody has a bodhisattva vow longer than this or that person…

(VTC): Yes, we don’t necessarily know if somebody else has had a bodhisattva vow.

Audience: So then you have to behave in front of everybody like this.

(VTC): Yes, well you know, it never hurts to show respect to others. I know I try and model it for other people. When I pass people on the path, I put my palms together, and technically speaking, if you were in a Theravada monastery, a sangha member would never do that. But I feel that it’s good for my practice, and I also want to show respect to others, and I go like this. But it’s really astonishing to me the number of people who don’t anjali back.

Audience: Why don’t they do that at Theravada?

(VTC): Because you have a higher level of ordination, and so you don’t even go like this to people who have a higher level of ordination. If you watch, with His Holiness, he’s always like this with everybody. I follow that example, and I think it’s just friendlier, and also, it’s better for my mind to show respect to other people. In fact when I was in Thailand, one of the people came up to me and said, “You don’t do that to lay people.” I was putting my palms together and saying, “Thank you.” They just said, “You don’t do that to lay people.”

Audience: Did you continue or not?

(VTC): I think I did but maybe not when that person was around. Because for me it felt so awkward, because I really wanted to show my appreciation to somebody else.

There are also very interesting ways in which we seem to show respect, but it’s kind of funny. Like when somebody comes in the room, and we don’t just stand up gracefully, but we pop up like this. It’s like, “Oh, I better act good or you’re going to criticize me.” And then you see that the person’s not really having respect, but they’re just doing it. Sometimes they’re communicating that “I don’t really respect you, but I don’t want you to criticize me either.” So, we have to make sure when we’re doing things, that we do it in a graceful manner, not in a showy, flashy way.

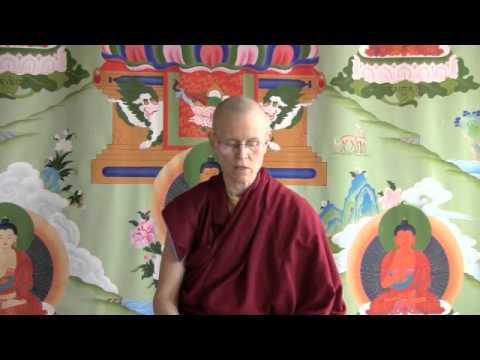

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.