Bodhisattva ethical restraints: Auxiliary vows 41-43

Part of a series of talks on the bodhisattva ethical restraints given at Sravasti Abbey in 2012.

- Auxiliary vows 35-46 are to eliminate obstacles to the morality of benefiting others. Abandon:

- 41. Not giving material possessions to those in need.

- 42. Not working for the welfare of your circle of friends, disciples, servants, etc.

- 43. Not acting in accordance with the wishes of others if doing so does not bring harm

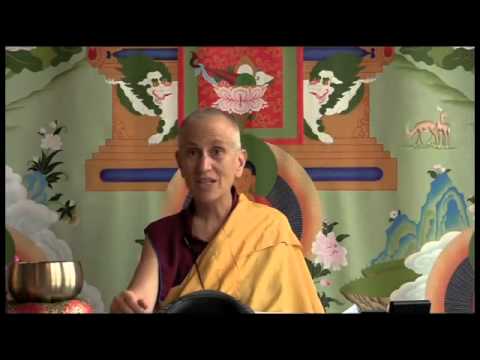

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.