Bodhisattva ethical restraints: Auxiliary vows 8-10

Part of a series of talks on the bodhisattva ethical restraints. The talks from January 3 through March 1, 2012, are concurrent with the 2011-2012 Vajrasattva Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey.

- Auxiliary vows 8-16 are to eliminate obstacles to the far-reaching practice of ethical discipline. Abandon:

-

8. Forsaking those who have broken their ethical discipline: not giving them advice or not relieving their guilt.

-

9. Not acting in accord with your pratimoksa precepts.

-

10. Doing only limited actions to benefit sentient beings, such as strictly keeping the Vinaya rules in situations when not doing so would be of greater benefit to others.

While we have our precious human life it’s very important to develop the determination to counteract the eight worldly concerns and develop the antidotes that actually counteract them. Although we may have a perfect opportunity to practice the Dharma, when our mind goes chasing after the pleasures and comforts of the eight worldly concerns, we waste this precious opportunity. Also, in the process we create a great deal of negative karma by doing things to procure and protect the things that will make us happy only in this lifetime. So, it’s always important to stretch our mind and consider future lifetimes, consider what samsara is, consider the situation of ourselves and all living beings in samsara. Thereby, with a very expansive mind that takes into account the big picture, make decisions, live our life, and do what is important in the long term, even if it means a little bit of discomfort or extra work right now.

That doesn’t mean to exhaust ourselves, but it does mean to have some stamina so that we can endure doing things that are even slightly uncomfortable or inconvenient. Because if we don’t have the endurance to do that, then it’s rather strange that we’re able to endure samsara at all and not counteract it. So, with a mind aspiring for your own and others’ liberation and enlightenment, let’s listen to the teachings.

The courage to endure hardships

I was thinking, it’s rather strange that we can’t endure minor discomforts and minor inconveniences, but we can endure samsara, which is filled with such incredible amounts of physical and mental stress, suffering, and so on. We’re so patient with samsara—“Samsara, no problem, no problem”—but some minor thing that we have becomes huge. Huge! It’s inverted priorities. Then we wind up really wasting a whole lot of time.

I was reading today about some Chinese masters giving advice about cultivating bodhicitta, saying how we must not have a weak mind, not be cowardly and timid, easily inhibited, and unable to bear anything, because if we are, that indicates a great deal of self-centeredness, doesn’t it? “I must always be comfortable. I must win. I must be right. I must have things my way. I must always have nice things.” And then absolutely no tolerance to endure even a minor discomfort for the sake of the Dharma. You can see that when our mind is like that, we waste this opportunity. Then on our death beds, we don’t have anything to show, because everything we spent our life on is gone. It was gone the moment after we had it.

I’m not saying we should push ourselves and become exhausted. That doesn’t make much sense. But to gradually develop some ability to have some fortitude and some endurance of different things. Because we endure a lot for the sake of this lifetime, don’t we? You go through this whole educational system, stay up all night to take exams, but we can’t manage to stay up until nine o’clock to meditate. We go through so much difficulty to keep a job. When you work, you can’t just take off every day that you don’t feel like going to work, otherwise they’re going to fire you. You must have the ability to go to work even when you don’t feel well and still be productive. You have a family you must still take care of whether you feel well, whether things are going your way or not, whether people are praising you or blaming you.

And yet when it comes to the Dharma, we can’t endure, we don’t seem to be able to endure anything. It’s rather strange, isn’t it? “I need my little empire.” I’ve noticed you’ve reduced your empires, but some of you are making good effort even with a small cloth, but you have reduced the size of your empires. So strange.

Anyway, we pledge to work for the benefit of all sentient beings from now until enlightenment, but we can’t endure anything ourselves. How are we going to work to benefit sentient beings when somebody does the smallest thing and we get upset, out of sorts, offended, insulted, and so on and so on. We must really think about what is important and keep our mind on that. Then these little things we just let go, let go, let go, because it’s impossible to arrange all our duckies so that they’re in line, it’s impossible to have nirvana and samsaric pleasure at the same time.

We’ve been discussing the bodhisattva vows, and to keep them we must endure a little bit of discomfort. Otherwise, we’re going to break them right, left, and center. We’re now going on to the “Misdeeds Contrary to the Perfection,” or the “Far-reaching Ethical Conduct.” There are nine secondary bodhisattva precepts pertaining to far-reaching ethical conduct. These are very interesting. There’s a lot to think about in this upcoming set.

8. Rejecting those of degraded morality.

Number eight, Chandragomin says, is “Rejecting those of degraded morality.”

Abandoning beings whose practice of ethics has declined is a misdeed that is described as rejecting the objects of particular compassion.

Those people who don’t keep good ethical conduct when we’re working so hard to keep good ethical conduct. You may think, “We’re enduring all these difficulties, and they’re not, and yet we’ve got to be kind to them and not reject them when they’re doing such stupid things. They’re ruining the reputation of the Dharma, and they’re acting like such enormous jerks, and that’s called, ‘Rejecting the objects of particular compassion?’”

Audience: Where are we coming from when we’re doing that? From pride?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Probably some pride, anger, maybe disgust, or disdain.

First, as concerns the object of the misdeed, Arya Asanga in his ‘Bodhisattva’s Levels’ calls them ‘the wicked and immoral who create the causes of their own suffering.’ There are two kinds of beings, human or otherwise, of degraded morality. The first are those who have not the slightest practice of ethics.

Somebody that doesn’t know anything about ethical conduct, or if they knew or they were taught, they don’t care beans. Just read the newspaper, plenty of them in public office and in other places as well.

They are completely immoral and lead depraved lives. The scriptures give us examples of people who have perpetrated one of the five heinous actions—[killed their father or mother or an arhat, for instance]—but such people are rare, so we should include in the first group all sinful people.

That word sinful drives me crazy. I have no endurance for that word. How about all people who create a lot of negativity? Those are the people in that group, not just the people who do the five heinous actions, but people who lie, cheat, steal, are dishonest and renege on their commitments, break laws, blame other people, create disharmony, and all that kind of stuff, people who do the ten non-virtues. It just sounds like us. He says:

There is no lack of them, and the desire to reject them comes very easily. However, those who practice the bodhisattva path should on the contrary feel compassion especially for them. Why? Simply because they have produced and most likely will continue to produce the causes for tremendous suffering for themselves in the future.

Dropping our biased views

We’re doing prison work here at the abbey, and sometimes when we mention to people that we’re doing prison work or that we go into prisons, they look at us like, “How can you do that, those people are so awful. They’re so dreadful, frightening, immoral, horrible, and indecent. How can you do anything for people like that, and how can you even bear to go in a prison to be with them?” People look at you in that way.

One of my friends who did his PhD developed an anger program for prison. He said that his experience in prisons, and to a large extent this is mine as well, is that some of the people are very difficult, but some of them are regular people who happened to get caught, while there’s a lot of regular people on the outside who didn’t get caught. Of course, it depends on what neighborhood you live in, what race you are, because the police will police different neighborhoods in a very different way. A lot of drug abuse and substance abuse by whites in wealthy neighborhoods is conducted inside, so the police who drive by are not thinking about that, they’re thinking to protect those people from burglars. But actually, those people inside of those houses are snuffing or shooting or drinking or misusing pills or whatever, but the police don’t see that, and they don’t catch it. Whereas in a poorer neighborhood, the drug business is done right on the street, so they police it, they see the people, and they’re easily arrested.

In any case, we have a lot of prejudice against inmates in our society, and once somebody is incarcerated, it becomes very difficult for them to get a job afterwards. People look at us sometimes when we say we’re doing prison work, like, “What are you doing with those people?” Like I said, some of the people that I write to clearly have mental problems, and rather than be in a prison, they should be receiving psychiatric help. In the prison they’re usually just drugged up so much, but they really need psychiatric help. Then there’s other people who have intense anger or intense desire, and it’s difficult for them to control. So they did something like that and got arrested, but who amongst us has never done anything impetuous under the influence of desire or anger? You might say, “Well, it’s not as bad as what they did.” That may or may not be true, we don’t know. Because it’s amazing sometimes the things that people have done that they don’t talk about. Presenting one image to the world, and then a whole other thing is going on in their lives.

What I’m trying to say is that to be prejudiced against people who are incarcerated is really quite unfair, and I think it actually leads to more problems, because those people are eventually, most of them, going to get released and go back into the community. They need jobs, they need housing, and they need good friends. For example, when I got the first letter, it must have been ’76, ’77, or ’78, from an inmate, I was so surprised because I had never thought of doing Buddhist prison work at all. It was because I have the bodhisattva vow that I responded to this person. And I didn’t tell my mother [laughter]. Bodhisattva vows overrule what your mother says.

Thus, this whole thing started that we’re now involved in, and it’s because of having this particular precept. Somebody wrote, and it was a sincere question, and I can’t just put the letter in the garbage, I must respond. So I did, and we have this whole prison project now.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: You’re saying that we’re told, not only by the media, but also by our school system, that somebody who is in prison is a bad person, and we don’t question it, we just go along with it. And you’re saying that there’s other countries that have different kinds of penal systems where they give the people some responsibility and they don’t have a criminal record following them around afterwards. And sometimes it can really turn out much better for everybody in that regard. A much lower recidivism rate.

But yes, definitely we don’t question what the news tells us. And what I find especially interesting is if a poor person does an illegal act, we have one attitude, and if a rich person does it, we have a different attitude. If a poor person breaks into somebody’s house to get money, we have one attitude, if a rich person embezzles thousands of dollars or cheats people out of millions of dollars, we have a totally different attitude. It’s really rather amazing.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: It’s the same here that the people who are poor, who don’t have legal representation, or in our country they have an attorney appointed to them. But usually that person doesn’t do very much, and so they don’t have adequate legal representation. But somebody who is wealthy can pay a top-notch lawyer, and as a result, they find some way to get out of prison, and we call it the justice system. Really rather amazing.

Anyway, this is a good thing, to watch our prejudice against people who are incarcerated, or even people who aren’t incarcerated who have done very negative actions. Watch how we are prejudiced against them or discriminate against them. Or how if a person is wealthy, has a scam, and gets a million dollars, we think that’s great. But if a poor person steals a hundred dollars, that’s really terrible. Watch how we sometimes praise the negative actions that people do.

The second group of people of degraded morality consists of those who have taken vows and made commitments to an ethic and have subsequently broken them.

This sounds like us. Of course, there’s major transgressions and there’s minor transgressions. Sometimes we meet people who have committed major transgressions and are no longer in the Sangha. Or if you look at what’s happening in the Catholic church right now, people having major transgressions. With precepts that aren’t root downfalls, like drinking or something like that, we may know monastics who have done that or have done other kinds of things like that. Sometimes it’s really tempting, the mind gets so critical of those people, saying, “Get out of here, forget it.” This precept is particularly against having that kind of attitude.

The action consists of forsaking or of scorning anyone who falls in either of these two categories.

I think I told you the Zen story about the Zen master who had one student who was awful, very obnoxious, not keeping the precepts very well, and so on. Other students, the very good students, came and said, “Why don’t you kick him out of the monastery?” And the Zen master said, “Actually, you’re the ones who should leave because you can handle yourselves, but he needs special attention and compassion.” So, it’s that kind of thing.

When it is out of anger or animosity that we look down on such beings or reject them, using their wickedness or their debased ethics as an excuse, it is a misdeed associated with kleshas.

Anger, animosity, and arrogance, because you’re looking down.

Doing so out of laziness or sloth is a misdeed dissociated from klesha.

So, its’s a misdeed, but it’s not as heavy.

Doing it because we have forgotten the bodhisattva instruction is a misdeed dissociated from afflictions as well. This is the case for many of the secondary misdeeds. When we simply forget to abstain from the action in question, it is still a misdeed, but one dissociated from afflictions. Thus, there are three ways to commit a misdeed dissociated from afflictions: out of laziness, out of sloth, and finally by forgetting the bodhisattva instructions.

All three of those are examples of misdeed not associated with afflictions.

There are several exceptions to this rule. It will not be a misdeed when we abandon these beings in any of the following circumstances.

There are some exceptions. One is:

We have a reason to believe that it is best to ignore the wicked person for the moment, for it will help him or her progress.

There might be a situation where it’s best just to ignore that person or not reach out because it will make them think a little bit more about what they’re doing and why and so on. It might help them in that kind of situation.

[Two,] We want to avoid upsetting a large number of people.

I don’t know what ‘a large number of people’ is, because some people when they do prison work are not very smart and go beyond a proper relationship when you’re a volunteer in a prison. They may have what Lama Yeshe called ‘Mickey Mouse’ compassion, saying, “Oh, fine, when you’re released just come and live with my family,” even though they don’t know the person very well. Or they don’t know why they’re imprisoned or how safe it is to be with that person. Out of some kind of funny compassion, compassion without wisdom, they say, “Oh, well, come live in my house,” and then your family gets very upset. Like, “Wait a minute, don’t we have a vote in who lives here?” and, “We want to have some say-so, too.” That might be an example of this one. In that kind of case where a lot of other people are going to be upset by your reaching out to help somebody with degraded morality, then it’s better not to.

The third situation is:

Looking after them would be contrary to monastic rules or social conventions.

If taking care of that person would make you break your monastic vows in one way or another. Or if it would be really opposite to social convention such that people would get all stirred up about it and wonder what are you doing being a Buddhist acting in this kind of way. In those kinds of situations it wouldn’t be a transgression.

Here’s an example. Once in a while, I get letters. Sometimes they’re from people I don’t know, but mostly they’re guys that I’ve been writing to. They’ll say, “Oh, my release date is coming up, can I come stay at the Abbey? I need a place to sign for where I can go live when I’m released. Can you do that?” And I usually say no. And the reason is, first of all, it’s not my decision to make, it’s something that belongs to the whole community to make. Also, because I feel that when somebody is released from prison, they need to get themselves on their feet in regular society. Then when they’ve been able to do that, if they want to come to the Abbey, they know very clearly what they’re giving up. Otherwise, sometimes taking them in here is a route for them to escape being responsible for themselves, getting a job, earning a living, re-establishing relationships with their family, and so on. So, it’s better for the person. It’s going to be harder for them for sure, but it’s going to be better for them to get themselves set up in society and not just come here because we’ll take them.

9. Not training for the sake of others’ faith.

Number nine, Chandragomin says, is “Not training for the sake of other’s faith.” What does this one read as?

Not acting according to one’s vowed trainings when it would generate or sustain faith in others.

The previous one was, “Forsaking those who have broken their ethical discipline, not giving them advice or not relieving their guilt.” So, this means really reaching out and helping those people with broken precepts or who just don’t have much ethical conduct to start with.

This fault consists of not following the common rules according to our vows for individual liberation [our pratimoksha precepts]. To inspire faith in others or strengthen the faith they have we should respect all aspects of the precepts of individual liberation that we have by abstaining from drinking alcohol and eating after noontime, for example. By failing to do so and thereby shocking or disappointing others, we transgress not only the precepts for individual liberation but also the bodhisattva precepts. The fault therefore concerns those who have taken the precepts for individual liberation, such as monks’ or nuns’ precepts, as well as the bodhisattva precepts.

As we go on, it comes out that this also applies to lay practitioners who have the five precepts, not just to monastics. But the gist is that when not keeping our precepts for individual liberation, we should be keeping them, especially when it’s going to make other people lose faith in the Dharma, lose faith in us, or have a critical mind.

When we fail to observe our discipline for lack of faith and respect, we commit a misdeed associated with afflictions. Disrespect leads to looking down on it or to minimizing its importance or to thoughts such as, ‘That’s for the people who follow the hearers’ vehicle. As a follower of the Mahayana, I don’t need to worry about those lesser aspects of the monastic discipline. It really doesn’t matter if I drink a little alcohol once in a while or eat after noon.’

You find people who have that attitude.

If we neglect to observe our precepts for individual liberation out of laziness or sloth, it is a misdeed dissociated from afflictions. Once we have taken ordination and have committed ourselves to the bodhisattva precepts as well, the observance of our monastic precepts takes on even greater importance. We should respect the precepts of ordination for the sake of others as well as ourselves, to inspire faith in lay people, strengthen the faith they have, and prevent it from decreasing.

We’re coming to a bodhisattva precept soon where you’ll hear very generally that the bodhisattva precepts in working for the benefit of others trumps the precepts for individual liberation, meaning that the bodhisattva precepts are more important. If you have a bodhicitta motivation, if you don’t follow the individual liberation precepts, it’s not so bad. So, there is that thought, but many people use that as an excuse to not train their mind according to the precepts of individual liberation, saying, “Oh, but the bodhisattva precepts are more important, and I’m doing this with bodhicitta for the benefit of all sentient beings, so I don’t have to… If I tell a little white lie, it’s okay; if I cheat on my income tax, it’s okay; if I do this, that, and the other thing, it’s okay because I’m doing it for the benefit of sentient beings with bodhicitta.” And you hear this all the time. There is truth that if you really have bodhicitta, that is the case. If you really have a good motivation, that is the case. But if we don’t, if we took the pratimoksha precepts, we should keep them.

People have different ways of keeping them. In the precepts for individual liberation there are exceptions for things, like for the one about eating in the afternoon. If you’re sick, if you’ve been doing manual labor, if you get wet because it’s raining, if you’ve been traveling, if you’re exhausted, something like that where it’s going to adversely affect your health or adversely affect your ability to practice, then it’s not a transgression to eat in the afternoon.

In terms of the alcohol one, for tsog, you dip your finger in, take a piece of the two substances, and put it right here on your lip. But I remember one time, when Alex was giving a talk in Seattle many years ago and afterwards we did tsog. It was just a group of people I didn’t know, and they start pouring beer out for everybody, including me. Alex and I are looking at each other, and we said, “Excuse us?” “Oh, well, this is what we do; tsog is a party. We have a party, and we’re tantric practitioners, so this is okay.” No, no. I think I got the point across here.

Audience: We had a young woman who came here, and I was telling her, “We’re getting ready for tsog.” She looked horrified. Her face was really scared, and I said, “Gosh, what’s going on?” And she said, “Oh my gosh, I’ve had really bad experiences with tsog.” Then she proceeded to tell me that she was at the center, the lamas got drunk, it was just a giant party, and it was really scary for her. Then I said, “No, that is not what you’re going to see here.” She really enjoyed it, and she stayed for a month, but it was really interesting how scared she got.

VTC: This is a good example. You’re saying that somebody came here, and when you said that we were going to do tsog, she got very frightened. Then when you questioned her about it, she said that she was once at a tsog where the people got drunk, and that was very scary for her. I imagine it makes you quite disillusioned, as well as frightened. Here are these people who are teaching you, and they’re really loaded. How much can I trust these people? That’s a very good example, it destroyed somebody’s faith. So, we should always take care and keep our precepts well, not only for our own benefit but for the faith of others. Sometimes the way we keep precepts here isn’t the way people keep them at other temples and so on. When we go there, if they keep something stricter than we do, then we follow what they do. If they keep it looser than we do, we don’t follow it.

Audience: If you follow the precepts, how can you follow it stricter or not stricter?

VTC: Like this thing about eating in the afternoon. I have a friend who is a Theravada nun, and she’s had two heart attacks. When she was recovering from her heart attack, she still didn’t eat in the afternoon. That’s how strict they keep it. People will have incredible health problems because they keep the precept very strictly, whereas in our tradition we say you need to keep your body healthy. It’s very, very important, because if you don’t have good health, then it becomes very difficult to practice. So, if you eat in the evening because of health reasons, there’s not a problem. Or if you’ve been doing a lot of manual work, you’re tired and need the energy.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: If you’re someone in the Tibetan tradition, you’ve had two heart attacks, you eat in the evenings for health reasons, and you go to a temple where they don’t eat in the evening, what do you? I would think in that case, if you feel that you need to eat for health reasons, don’t stay in the temple because they don’t serve food and would probably get very upset if you’re a monastic in their temple eating in the evening. But if you felt your health was good enough, and for one day you could not eat in the evening, then go. I think it depends on the situation.

There are many different precepts like this. In the west we’re often pulled in very different ways because the lay people don’t know the precepts. Often, if we’re with people who keep the precepts in a different way, they want us to do another thing, so we often can’t please everybody. We must negotiate it one way or the other, and that’s just the way we do it.

How this restraint applies to lay practitioners

There is some discussion amongst learned masters as to whether this secondary misdeed refers to everybody who has the bodhisattva vow or specifically to those who have taken the ordination precepts, in other words, monastics. Bodhibadra, one of Lord Atisha’s spiritual masters, said in his commentary to Chandragomin’s ‘Twenty Verses’ that this precept is primarily meant for the ordained. However, ‘The Great Way’ adds: ‘Nevertheless, it seems that a large number of the precepts for lay people with the vows of individual liberation are common to the precepts of ordination.’

For a lay practitioner, the main precepts are not killing and stealing. The one about sex is different, but not lying, not taking intoxicants and so on, they’re very common. So, it would apply in that case to somebody who is a lay person, too.

It’s important if you’re a lay person to keep your precepts when you’re with other people and to not have this mind, whether you’re ordained or lay, that says, “But it’s just a little white lie, and if I tell the truth, people are going to be offended.” Which often means, “I did something I don’t want other people to criticize me for, so I don’t want to tell them.” We must learn to be straightforward and think about our ethical conduct. And of course, admit our mistakes when we don’t keep it. That’s why we do purification on a daily basis and why as monastics we do the posada twice a month.

This is why the misdeed is described as ‘failing to train in the common rules.’ Lay practitioners of the bodhisattva path who also have the precepts for individual liberation should respect both categories of precepts by abstaining from drinking alcohol, for example.

Basically, what this precept is about is not rationalizing breaking your pratimoksha precepts by saying, “I’m working for the benefit of sentient beings.” That’s basically what it boils down to. Because when we rationalize that, it disturbs other peoples’ minds.

I heard this story from one monastic who, I don’t know where they were, but people were smoking grass, and he started smoking grass, and one of the people looked at him and said, “You’re a monastic, aren’t you supposed to not do things like this?” And he continued. And I said, “Well, what did you say?” This monastic said, “Oh, I just said, ‘Well, you know, I’m human.’” That’s what he said to the other person. But this is the kind of thing that if you have the bodhisattva vow, really think about the effect of your behavior on other people.

Audience: Sometimes when they invite you, sometimes the food has alcohol or wine or something like that and you don’t know.

VTC: What about when food has alcohol? If the food is cooked, the alcohol is no longer active. I usually recommend though, that if you have a proclivity for alcohol, even though the alcohol is not in the food, the taste of the alcohol could make you start craving it, so it might be better not to eat it. But, technically…

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Or if you don’t know the person before you go to their home, just mention it to them and say, “By the way, I know a lot of people cook with alcohol, but I thought I should let you know that I don’t eat food like that.”

10. Doing little for the sake of others.

Number ten is “Doing little for the sake of others.” Here it says:

Doing only limited actions to benefit sentient beings, such as strictly keeping the vinaya rules in situations when not doing so would be of greater benefit to others.

Here’s that thing, it’s a situation where we have a choice between keeping a vinaya rule or doing something of great benefit to others. If you say in your mind, “Oh, but I’ve got to keep this absolutely, completely, strictly,” and as a result, you miss out on the opportunity to benefit somebody, that is a break of this precept. On the other hand, if you rationalize your wish to break your precept by saying, “I’m doing it for the benefit of others,” then you break the previous precept.

Audience: Can you give an example of the first situation, where you should break the vinaya in order to benefit a number of people, what would that look like?

VTC: For example, we have this thing with our robes where we must ‘determine our robes,’ or ‘declare our robes,’ declare that they belong to us. If at the same time you’re supposed to do that with somebody but there’s the opportunity to really do something beneficial for somebody else that would have a really great impact, you give that up and say, “Oh, but I have to go and do this ceremony to declare the robes.”

Audience: It’s the ceremony you would have to leave to do that and help the other person, I see.

VTC: I faced this situation many times because I’m not supposed to be alone in a room with a man. But when I do interviews, somebody doesn’t want everybody else to hear, so you sit alone in a room with a man, but there’s a window in the room, and you tell other people what you’re doing, and so on and so forth. Because if somebody came to me very upset and I said, “Oh, I’m sorry, I can’t talk to you,” or “We have to talk in the middle of the dining room,” then that would be quite difficult for the person.

‘The Great Way’ describes the tenth secondary misdeed as ‘following specific rules.’ It involves failing to do things that would be helpful to others because we strictly observe the specific rules of the precepts for individual liberation. In his boundless compassion, Lord Buddha manifested himself as a monk for the welfare of all living beings.

He’s going to lead into an example here.

To allow living beings to develop their good qualities and reduce their faults, he underlined the importance of having few desires, scant possessions, and of being content with what we have. Lord Buddha lived by these rules himself and placed them at the very core of the monastic training.

Simplicity is, in terms of possessions, at the core of our training.

He taught monks and nuns to follow these principles so that they might avoid committing many ill deeds. When we do not retrain our desires, we often get involved in harmful activities and thereby create considerable negative karma. On the other hand, by limiting our possessions and contenting ourselves with reasonable quantities of plain food and clothing, we also reduce the number of potential objects of attachment. Furthermore, as we are not caught up with acquiring ever more belongings and maintaining the ones we have out of greed and attachment, we are left with more time and energy to devote to study, reflection, and meditation.

That’s the reason the Buddha set out many of the precepts for monastics, so that we live a simple lifestyle, we don’t have a lot of possessions, so that we’re not involved in thinking, “How am I going to get this, how am I going to get that?” We’re not involved in taking care of these things, and we’re not going to get upset if they get broken and lost because we don’t have them. So even as a monastic, we have to think about when we buy things for the monastery, too, and not just think, “Oh, this is for the monastery, we can buy it.” We should really think, “Is this something that we really need?”

As our minds become stronger and more resistant to selfish desires, the wish to do more for others grows proportionally. We should then go beyond the initial step and instead of limiting the number of our effects, increase them so that we can use them to help others around us.

Once you have a handle on your desire, your bodhicitta has increased, and you really want to be of greater benefit, it makes some sense to have more possessions if you use them for the benefit of others, or because with that change in your mind you want to use them for the benefit of others.

Logically, once we have realized bodhicitta, taken the bodhisattva vows, and are firmly intent on helping countless living beings, the monastic principle of limiting our possessions no longer applies, for it restricts what we can do for others. In fact, for the sake of others, never ourselves, we should have as many goods as we can.

But it’s for the sake of others, never ourselves we should do that. Again, we don’t use this a rationalization to say, “Well, I’m practicing the bodhisattva vehicle, so I don’t need to have a simple lifestyle, I should have all these things because I use them for the benefit of others.” So not to rationalize and say that kind of thing.

In the context of bodhisattva practice, persisting in owning few possessions is therefore a fault, as it conflicts with service to others.

This is talking about a person who is at a certain level in their practice.

We commit a misdeed associated with afflictions when out of anger or animosity, without regard for others’ well-being, we think, for example, ‘Never mind other people, I’m just going to continue to live in this small hut, or small apartment, it gives me less work.’ Limiting our belongings out of sloth or laziness is a misdeed dissociated from afflictions.

So you have great bodhicitta, but it’s like, “I don’t want to take care of all this stuff, and clean so much stuff, so I’m going to continue with my simple lifestyle,” instead of having more things that then you can use for others.

Nevertheless, until we gain control over our minds, and as long as we are still subject to many disturbing factors such as attachment, it is better to keep few possessions and content ourselves with less. Once we have fortified ourselves with a strong altruistic aspiration to enlightenment and are no longer vulnerable to the afflictions, owning great wealth is a notable advantage in bodhisattva practice. Possessions and wealth as such are neutral. It is only when having them prompts our disturbing factors that it is better to limit them. When great wealth no longer stimulates our afflictions and we can use it to benefit others without risk, it is a great gift. Each of us must determine which is our case.

I would add that even if you are at a level where you can have great wealth and it’s not going to affect your mind, it might still be better for other living beings if you show the aspect of living a simple life because they need to have a simple life. The teacher might have bodhicitta and be able to do all sorts of things, but if they do that, the students are going to say, “But our teacher has a Mercedes, and our teacher has this and this and this, so it must be okay,” because people copy their teachers. So, if you’re the teacher in that situation, if your disciples aren’t really capable, they don’t have that level of mind, and they have a lot of attachment to these things, out of kindness for your disciples you should, even though you aren’t attached to these things, still live a simple lifestyle. Like Lord Buddha did. That’s why the Buddha stayed as a simple monk. He could have had a lot of possessions, but he chose not to, and it was an example for us.

This gets into some very interesting topics, because as individuals we may not have a lot of possessions, but sometimes monasteries have a lot of possessions. The prayer hall might be filled with all sorts of things, or even the place where you receive guests, very lavish, beautiful furniture, china dishes, and all sorts of incredible things. It’s an interesting thing. I remember talking with one lama about this and his feeling was, if you have a very beautiful temple and these kinds of very nice things, even the place where you receive guests, then more people will want to come to the temple, and that’s good for the people, it attracts them.

And my argument was, “Well, yes, I understand that, but then it could also make other people criticize the temple because the temple has more wealth than they do.” And if you look, this was one of the main criticisms that communism had against Buddhist temples. They were so wealthy, and many people in the ordinary population were very poor. It really created a lot of bad feelings, and this was the rationale for destroying the temples and the monasteries.

So, it’s an interesting question. And sometimes you meet lay people who really want the temple and the monastics to have very luxurious things. Maybe they’re somebody that’s quite wealthy, and they have a lot of respect for the Sangha, so they want to give all these kinds of things. In one way, they have a mind of faith, it makes them happy. Other people also might be happy to see such beautiful things around when they come to the monastery. Some people might be pleased by that. Other people might really criticize it. I thought, “These people renounced, so why do they live in a place where they have more luxury items than we do?” I tend to be quite sensitive about this and side with the latter position. But I certainly have been to temples where I’ve seen the other thing, the incredible stuff that they have. And I always feel a little bit uncomfortable, like, “We’re renunciates, you know?”

I’ve also been to temples, or I’ve seen different people who receive a lot of donations, a lot of gifts and things like that, but they don’t really keep it in the temple, they use it for social welfare projects. Instead of using the money and so on to beautify the temple, they do projects for society. I remember once I was at a temple in Penang, Malaysia, and I was so impressed there. I finally met the master from there, a few months ago. He wasn’t there when I visited. It was quite a large temple, it wasn’t very elaborate or anything, but he had set up an old folks home and a kindergarten for the kids, and he had the little kids go and visit the old folks. It was perfect. It was so good, because the old folks were just delighted and so happy to see all these little kids. Then he had a clinic, and I was thinking, “Wow, this is so wonderful.” And it’s because there were disciples who gave him the money, and he chose to use it in this way. Also, because he had many disciples who ran these things, so there were many volunteers. He might have paid a few people, but many, many volunteers doing this. And it was very beautiful.

And when I went to Singapore, also Venerable Fatt Kuan, I stayed at her old folks’ home when I first arrived. She had a temple and used donations to make an old folks’ home for destitute old women so they had a place to live. A few times a week they would all do chanting together. It was very sweet. She’s the one who built Taipei Buddhist Center, the place where I teach. She used the donations that she received and built a huge, very beautiful Buddhist center. It’s very simple but beautiful, and all the different Buddhist groups can use it.

You see people who use their offerings like this, in a positive way for society. I think it makes other people happy, and it stops criticism. We should do something to benefit society. This is something that Buddhism has been much slower to do than Christianity, for example. Because sometimes we’re so focused on, “Let’s get out of samsara,” and doing our meditation and study to get out of samsara, that we don’t get involved in these social welfare things. On the other hand, you can get involved in the social welfare things and be so busy you have no time for practice and study, and that’s another extreme. What’s very good is within a group if you have some people that are more inclined to offering service, they do those projects. Then the other people who are more inclined to study and practice can do those things, so you have some kind of balance in there. I think it’s good.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: The question that came up about how to work with the beggar situation in Bodhgaya. When you were on a program abroad, they gave you a list with the authentic charity organizations that really help the people in the area. Yes, that’s very good.

Audience: I was thinking some more about number eight. Is it just having critical thoughts initially?

VTC: Number eight, the one about the people of depraved morality. It’s not just a passing critical thought, but it’s getting so negative, like, “I don’t want to have anything to do with this person.” Kind of having no compassion towards their situation. On the other hand, if it’s going to be better for that person if you remain aloof so that they get the idea, “Oh, I did something that’s not so good,” then that’s something else.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: It’s the situation of somebody that you might have a very judgmental attitude about. They’ve pushed your buttons because they’ve broken precepts, or they have no ethical foundation or something like that, and they’re doing a lot of negative actions. It has pushed your buttons, and you get very critical of them. You’re saying you realize that you’re critical of them, and you really want to have a kind heart towards them, but at that moment your afflictions are so strong that it’s hard to get from point A to point B.

I think just the fact that you notice that your mind is critical and that you have the idea of, “I don’t want to think like that,” already you’re opposing that negative thought. You’re realizing that there’s something wrong with the way you’re thinking, that it’s opposite to the values you have. And even though the afflictions are very strong at that moment, and you can’t control them, you’re definitely going in the right direction.

Maybe you can’t control your judgment at that time, but later you go back and sit on the cushion, and you really work with your mind. Then you develop more understanding and compassion for that person. The precepts are designed to lead us in the direction we want to go, so we must try. Just like the other one, the second auxiliary one, about following thoughts of desire. We’ve got to try to oppose them, and if we try and still fail, we’ve done our best. It’s not a full transgression like that. But if we just say, “It’s too strong, I’m not even going to try,” or we just buy into the idea the afflictions staying to start with, then we’re going opposite to the bodhisattva way.

We sometimes see that when other people do behavior, we’ll feel disappointed in them, or disillusioned or something. They’ll do something negative, and we thought, “But I thought you were beyond that.” And then they do something like that. When that happens, really work on trying to develop some patience, fortitude and compassion for that person. It’s not the ‘Mickey Mouse’ compassion of, “Well, it doesn’t matter what you did,” but compassion that frees us of our judgment.

On the other hand, when it’s us, and we’re tempted to break a precept, we shouldn’t just say, “Well, other people need to be compassionate with me, it doesn’t matter if I break my precepts,” because that is going against the following one, which is not keeping our precepts when it would cause other people to lose faith or be disappointed in us, or in the Sangha, or in Buddhism in general, or whatever.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, “Others are so compassionate, it doesn’t matter if I break my precepts.” No.

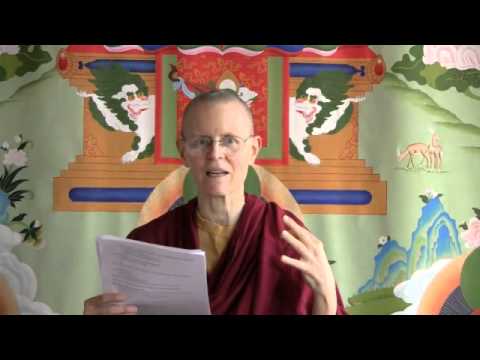

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.