Bodhisattva ethical restraints: Vows 9-11

Part of a series of talks on the bodhisattva ethical restraints. The talks from January 3 through March 1, 2012, are concurrent with the 2011-2012 Vajrasattva Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey.

- Vows 9-11 are to avoid:

- 9. Holding distorted views (which are contrary to the teachings of Buddha, such as denying the existence of the Three Jewels or the law of cause and effect, etc.)

- 10. Destroying a (a) town, (b) village, (c) city, or (d) large area by means such as fire, bombs, pollution, or black magic.

- 11. Teaching emptiness to those whose minds are unprepared.

Bodhisattva ethical restraints: Vows 9-11 (download)

Motivation

Let’s generate our motivation. Think of our fortune in being able to listen and discuss the bodhisattva vows, bodhisattva precepts, so we can learn what the behavior of bodhisattvas is. By learning how bodhisattvas think and speak and act, then it’s clear in our own mind how to think and speak and act, what to practice and what to abandon. Doing this will enable us to progress through the stages and accumulate the causes and conditions to actualize our spiritual aspiration to be of the greatest benefit to all living beings, through attaining the enlightened state of a Buddha.

A quick review

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Have you been thinking about the ones we’ve gone over so far?

Audience: A little bit.

(VTC): How about other people?

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Has it been helpful?

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): So, you’re able to see how these differ from the individual liberation precepts in that they’re really emphasizing actions of the mind, whereas the other ones are emphasizing body and speech, and also how much more detailed these are in terms of highlighting specific actions. Another interesting exercise to do is to look through these actions and say, “Do they fit in any of the ten non virtuous pathways? And if so, which ones? Because the ten non virtues are kind of the umbrella categories. And why is this particular instance of that particular one of the ten non virtues emphasized?”

What really strikes me, looking at the bodhisattva precepts, is you can see that they are designed for somebody who is not a beginning practitioner. Because a beginning practitioner is going to be familiar with the general actions of the five lay precepts. Then you get more technical going into those five, or into the ten non virtues, when you look at the monastic precepts. But here, when you look at these—praising yourself and belittling others out of attachment to honors and offering—is a new practitioner going to do that? Probably not, because they don’t really know enough to be able to praise their own good qualities. They may not be so jealous of other people who get things, because they realize they are beginners.

It’s very interesting. As you stop being a beginning Dharma practitioner, sometimes your mind can more easily create certain negativities than it did when you were beginning. Because when you are beginning, you don’t get arrogant about things. You’re just eager to learn and soak it all up. When you know a little bit, that’s when the arrogance and conceit come, isn’t it? “Oh, look how much I know, but that beginning person doesn’t know. I’m so great.” So, you get a whole new kind of way that afflictions can arise in your mind once you’ve been around the Dharma a little bit.

Similarly, with the second one—not giving material aid or giving the Dharma—material aid is something that may apply to everybody. A beginning practitioner isn’t going to encounter that because they don’t know enough Dharma to give it. It’s only somebody who is seasoned, who has been around a while, who is going to say, “Oh, I don’t really like this person,” or “I don’t want them to know the Dharma because then they will compete with me”—something like that.

That’s true with some of these other ones, too, like “Denigrating the hearer’s vehicle or causing people to leave their individual liberation precepts.” And the one we just did—“Saying that the Mahayana isn’t the Buddha’s teaching“—is a new person going to do that one? No, they don’t know Mahayana or the Fundamental Vehicle; they don’t know all of that. That’s going to be somebody who has been around for a while. Who’s going to denigrate the hearer’s vehicle? A new person? No, they don’t know enough! It will be somebody who has been around a while. Who is going to take the robes from a monastic, or give them, or not treat them properly, even if they’ve broken their discipline. Is that a new person? No, it’s going to be somebody who has some power because they’ve been around a lot. It’s very interesting to go through these precepts as we cover them and say who is it who is likely to be involved in this kind of behavior. Then we may see how one day we may be the kind of person who is going to be in a position to do this kind of action.

It’s quite interesting. It gives you a whole new perspective that sometimes when you know a little bit you have to be even more careful than when you don’t know very much. The arrogance can come more easily, the jealousy, the attachment, the anger, the clinging to my position in the community, “my reputation in the Buddhist world”: “I want material possessions,” or “I want to damage the Sangha. I want to damage specific monastics.” These are things that people who are very involved in Buddhism are going to do. Okay, the Beijing government, like we were saying before, they could destroy monasteries and things like that, but they don’t have the precept. Who is going to have the precept who could be stealing from the Three Jewels? It could be the caretaker of the altar, couldn’t it? Or it could be somebody who is really trusted in the community who thinks, “Well, nobody will suspect me of taking this, that, or the other thing from the altar”—something that was offered to the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha. It’s very interesting to think about these things.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes, it’s a very good point. In ancient times there were many kings who were Buddhists. You can see that some of these things are actions that somebody with a lot of worldly power could carry out against the Sangha. Nowadays we do have people who have some worldly position who are Dharma practitioners. I don’t know if they have as much power as the kings of the past, but still, when you have worldly power, then it’s very easy to do things that damage practitioners. You can see as we go through this that a lot of it has to do with taking, in one way or another, the material things that belong to the Triple Gem, or that are needed by practitioners in order to do their practice. We’re coming up on one where you don’t steal directly but you kind of cause the whole situation to happen with the intention of harming somebody who is practicing. So, it’s going to be somebody with some kind of power who has those bad feelings. It’s not going to be somebody totally unrelated to the Dharma because those people wouldn’t have the precepts, even though they may do some of the actions like them.

9. Holding false or distorted views.

Here we are on number nine from Shantideva, who says:

The ninth transgression is holding wrong views. Let us examine the object first. Here, the expression ‘wrong or false views’ refers notably to the opinion—

Here he’s delineating what kind of things.

—that enlightened beings, karma and its effects—the connection between our actions and our experience—and rebirth—past and future lives—do not exist. The action is holding these views even when we know full well that these do exist.

First of all, when he says “knowing full well that these things do exist,” I think if you knew full well, you wouldn’t be holding these wrong views, so I don’t know why that sentence is in there. I don’t understand that. Here he is referring to specifically saying, for example, “Enlightened beings or the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha don’t exist, or karma and the law of karma and its effects doesn’t exist.” In other words, there’s no ethical dimension to our actions, so we do whatever you want as long as nobody finds out, and we think that past and future lives don’t exist.

This isn’t just having doubt or having it on the back burner or something like that. This is holding a very rigid, stubborn, close-minded view that’s kind of like “Well, let’s see if you can make me believe in that.” Along that line, for example, a subsidiary would be saying, “It’s impossible to get enlightened. Not only the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha don’t exist, but there’s no way to get enlightened. There is no path to enlightenment. People are inherently selfish, so there’s nothing to do about it. This is all stuff made up just to make people be good. They want to threaten people with karma to make them be good.” It’s these kinds of things. And you hear people say this all the time.

But then you have to ask, “Why is this damaging?” Because this is also one of the ten non virtues. It’s the tenth of the ten non virtues. Why is this one damaging? It’s a free world. Why can’t people just believe what they want? What’s wrong with thinking that Buddha, Dharma, Sangha don’t exist, and that karma and its effects don’t exist, and rebirth doesn’t exist, and just saying that’s all just a bunch of rubbish?

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes, you won’t get enlightened. Why?

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): If you don’t think there are enlightened beings, then you don’t think there’s a path to get there. So, you’re not going to embark on that path. That’s something damaging to yourself, and then indirectly to others.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes, it throws your bodhicitta out the window, doesn’t it? If you think that there’s no such thing as full awakening, then how are you going to have bodhicitta? What else?

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes. It’s very easy to do negative actions because we don’t consider the consequences of our actions very much. Now somebody is going to say, “But do we need to really believe in future lives to realize that there’s an ethical dimension to our actions? Doesn’t that sound a little bit like what we learned in Sunday school? You don’t get punished now; you get punished by going to hell afterwards? Isn’t it an awful lot like that? Wasn’t that just invented to teach people, all these kinds of shepherds and goat herders, to be nice? We’re sophisticated twenty-first century intelligent people. We don’t need to be made afraid in order to know not to do negative things.”

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): You wouldn’t understand that by looking at the world? Why?

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): You’re saying people nowadays, many of them, don’t consider the effects of their actions, even in this lifetime, and just have a very reckless attitude of “well, whatever” or “as long as they don’t find out about it.”

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes. People get impatient. “Why do I have to wait to become enlightened? I want something quick.” They think this whole thing about looking at the results of our actions is a real key thing. I remember with one of the people in prison that I wrote to for quite a long time, one of his big realizations when he was incarcerated was “The decisions I made in my life are what got me to being incarcerated.” He spent a good deal of time at first being quite angry at other people, because when you’re first busted for whatever, it’s always somebody else’s fault. We know that, and we haven’t even been arrested for anything. Well, maybe we have. But even if it’s not something you would be arrested for, we always say it’s somebody else’s fault. But then, when you sit in prison for a while, you’re going, “Well, how did I get here anyway?” He wrote me this long letter and really traced certain conditions that he came in contact with as a child, and his decisions on how to act in those circumstances, and how those decisions led him to be in other situations in which he made other decisions, and that led him to be in other situations where he made other decisions, and so on, and so on. He could trace exactly how he got into prison. And this was a big ‘a-ha’ thing of “Oh, my actions have results.”

And yet so many of us in our life don’t think of the results of our actions. Even in this lifetime we don’t think, “If I do this, what’s the result going to be in this lifetime?” Much less do we think about what the result is going to be in future lifetimes.

But cause and effect exist. It exists on a physical plane; everybody knows that. Why do people go to work? It’s because they want to make money. There’s a cause, and there’s an effect. People believe in certain kinds of causes and effects, but in a way we just kind of go into outer space and say, “Well, these actions don’t lead to any kind of effects; they just disappear. And as long as you don’t get caught, then it doesn’t really matter as long as nobody knows about it. It doesn’t really matter.”

What I find so interesting is you see that anybody who enters politics nowadays, their whole past gets investigated and all this stuff gets dredged up. But at the time they did those actions, did they ever think, “Oh, I might be running for political office, and this is going to be dredged up?” No. Nobody thought like that. They just thought, “Why not? I can get some benefit from doing this, that or the other thing. It doesn’t really matter.” Then, years later, all of it gets dredged up. Then they’re very busy talking this, talking that, trying to explain their things, and doing everything except saying, “I made a mistake.” They won’t say, “I made a mistake.” They may go as far as saying, “I’m sorry that happened,” but they will not say, “I made a mistake.” It’s interesting, isn’t it?

These wrong kinds of views, when we’re not careful, can take us down quite a slippery slope and get us into all sorts of strange situations.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): I don’t understand. If somebody says that the Buddha wasn’t already enlightened when he was born but actually practiced in this life and attained enlightenment…

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Some teacher was saying that he’s like a therapist.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): The Buddha was like a therapist?

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Oh, I see. I see. So, it’s somebody who is not teaching all of the Buddhadharma, but just, let’s say, what the Buddha’s saying about emotions but not teaching about karma and rebirth and those kinds of things.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Okay, he’s neglecting that the Buddha taught about that. That would fall under one of the earlier ones, wouldn’t it, of saying abandoning the Dharma by saying that the Buddha didn’t teach certain things?

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): If somebody has wrong views, and they’re in a position of giving Dharma talks, and they’re espousing their wrong views, then that can be very bad for the Dharma.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes. Point nine is regarding if you have wrong views. You don’t even have to tell anybody; you don’t have to teach them. You just have them. But you can see that doing so is damaging for oneself as an individual, and then if you’re in a position where you teach that to others it’s even more damaging.

There are some things that it takes us a while to really develop some confidence in, but that doesn’t mean we have wrong views about them. This is especially true when it comes to rebirth. I certainly didn’t grow up with that idea. It wasn’t an automatic part of my cultural background and the assumptions that I grew up with. So, getting used to the idea of rebirth is one thing, but saying, “Oh, it absolutely is a bunch of nonsense,” is another thing. Here we’re talking about somebody who really has a very stubborn wrong view.

Generally speaking, a false view can either be an assertion that something exists when it does not—

That’s like the view that inherent existence exists even though it doesn’t.

—or the denial of something that does exist.

That’s like saying, “Karma and its effects don’t exist.”

However, this transgression involves only the latter, which is far more serious than the former.

I would think it would depend on different things in the former. It would be if you start saying the Buddha is some creator being, or there’s an inherently existent state of enlightenment that we’re all part of, or there’s a cosmic mind that we’re all going to dissolve back into. I think that’s also quite damaging to people.

The nature of the major transgression, holding false views, is identical to one of the ten non-virtues, the last of the three harmful mental karmic paths. Committing the ninth major transgression does not require making others share our opinions, nor is the presence of the four binding factors necessary. In fact, we annihilate our virtue and lose our bodhisattva vows as soon as we entertain one of the above-mentioned wrong views.

So, it’s just having that. Here, “entertain” doesn’t just mean a light kind of thinking. It’s deep in your mind. You can see you don’t have to say anything, you don’t need the four binding factors, which we’ll come to, it’s just thinking in this way. It can be quite dangerous.

10. Destroying places and so forth.

Number ten from Shantideva says:

The tenth major misdeed involves destroying places. The object—places—includes villages, towns, regions and provinces, but not the people living in them. The motivation is the intention to destroy a place, provoked by a klesha, by afflictions. There is no desire to steal, for example, but simply to destroy. The action is demolishing by any means. This brings war to mind. Although in a war it happens that places are wrecked, this is not usually the main objective.

Because in a war usually you want to harm the people. The place is secondary.

Here, the specific aim is to ruin a place. A relevant example would be arson, purposely setting fire to the house of someone we don’t like.

Of course, there, the person could be inside, so you want to harm them, too. But this is specifically, you don’t want to necessarily harm the person; you don’t want to steal the possessions—you just want to destroy the habitat where somebody lives.

Not razing a town but killing or wounding its inhabitants could be the third major transgression, ‘striking others out of anger. ’ But not this one, the tenth. If we confiscate the peoples’ property, the fault is of yet another nature.

That cause is more that you’re stealing.

It may be the fifth, taking that which belongs to the Three Jewels, or the sixteenth, inflicting fines on ordained persons and accepting what has been offered or what was intended to be offered to the Three Jewels. But, in any case, it is not the present fault.

Some transgressions are called ‘king’s transgressions,’ and others ‘minister’s transgressions’ because people in positions of power are most likely to commit them.

Following Shantideva’s list of downfalls, the first five that he talked about—in other words, numbers six through ten—are said to be the king’s transgressions, because the kings have the power to do this, and the present one, a minister’s transgression. Yes, five to nine would be the kings, and this one the ministers. But it seems to me a king could do this one, too.

Anything about that one?

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Here, it’s specifically talking about human habitats. I’ve often thought about that. Because we’ve relocated the ants, and so on. But here, it’s specifically specifying human habitats—just wanting to destroy.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): People can have all sorts of motivations. You’re jealous of somebody. Somebody else has a very nice monastery or a very nice house, and you’re jealous and want to destroy it.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes. Because the most important thing somebody possesses is their life. That’s the killing precept. Then the second thing is that in order to stay alive, you need certain material things. If somebody is destroying those material things, especially the place where you live, then you have no home to go back to and you’re exposed to the elements. All your wealth is taken away, and now you’re just trying to put your life back together.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): It seems funny, okay. Here’s somebody who has gotten to the level where they’re taking the bodhisattva vow, which means they have some kind of intention for enlightenment, and then they would go out and destroy a town or set fire to somebody’s house or whatever.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Well, we’ve taken the bodhisattva vow; do we always have virtuous minds?

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): These things seem extreme. I think that’s one of the reasons why they are root infractions. To commit a root infraction, your mind really has to be in a state where you’re really overwhelmed by negativities to get yourself to the point where you would do something like this.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): No, remember I said at the beginning that these are things that were found throughout the Mahayana sutras, that Asanga and later Shantideva extracted and made into a series of bodhisattva precepts. They didn’t occur through specific situations like the precepts of individual liberation did. But you could also see maybe there’s somebody who develops psychic powers, and then they think, “Oh, wouldn’t that be interesting to see if I can destroy this, that, or the other thing—some place where people live.”

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): We’re always so shocked! It’s even happened here. We may know somebody very well and they seem to be really doing good work on the Dharma path, and they’re really making a lot of progress, and then wham! They’re like out in left field! And we’re so shocked. How could this person who has been coming to retreats, and done this, and this, and this, go and do that? Because they are human beings, and we are under the influence of afflictions and karma.

(VTC): That’s a very good example. Look at what people do when they’re getting a divorce. The person that they love so much now they have so much vile hatred toward that same person. And you could never even imagine it would have happened.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): If you take away somebody’s house, that would be stealing. Here we’re talking specifically about destroying it. That’s a different state of mind. You steal it because “I want it.”

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes. It’s the idea of “I want to damage you. But, you know, I’ll taunt it. I want to damage you. The fact that I have it and you don’t, will really hurt you.” Whereas this one is just the mindset of “I want to destroy.” It’s slightly different than stealing. I mean, it still could be the same motivation, to harm somebody, and have some similar effects.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): In that kind of thing, like when a government buys something to build the freeway, they compensate the people, hopefully.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes, but that house has been their house; it no longer belongs to the other person.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): No. It has to be somebody else’s thing, I think. It’s not destroying your own property. Otherwise, what about when you take down a building because you want to rebuild it? This is intentionally destroying somebody else’s property.

11. Explaining emptiness to unprepared beings.

We’re on number 11. Shantideva says:

The eleventh major transgression is incurred by teaching the profound concept of emptiness to those who are not qualified to hear it. In the words of the ‘Six-Session Guru-Yoga,’ it is ‘teaching emptiness to people who are untrained.’

Now, I’m going to read the way he described it here. But it isn’t the way I’ve previously heard it explained, and also there’s some points of it that seem strange, okay? So, I’ll go through what he wrote here, and then I’ll tell you the way I’ve usually heard it.

The object is any unfit person, in other words, anyone who is not sufficiently trained in the stages of the path to enlightenment to understand the notion of emptiness and who is therefore in danger of being frightened by it.

That part is easily understood. Somebody who doesn’t have sufficient awareness of the lamrim and of conventional reality is in great danger of misunderstanding emptiness so that they think that nothing exists.

People need to prepare themselves by training gradually in the paths shared with persons of lesser and intermediate motivations before they can tackle the topic of emptiness without risk.

That’s for sure.

The object is an insufficiently-trained person who follows the great vehicle, aspires to realize enlightenment and has taken the bodhisattva vows but has yet to meditate the stages of the path to the point of realizing bodhicitta. As a result, he or she runs the risk of being profoundly troubled by the notion of emptiness.

Here, he’s limiting the person to somebody who is a Buddhist who has taken the bodhisattva vow, and he explains why as follows, and this is the point that I have a qualm with.

The action consists of rashly teaching emptiness to unsuitable people. The transgression is complete if followers of the Mahayana—

So, he’s specifically saying followers of the Mahayana.

—as a consequence of our explanation, misinterpret emptiness to mean that nothing exists and take fright. They then think that achieving Buddhahood is too difficult and conclude that it would be better to give up the idea of enlightenment and seek personal liberation from samsara instead.

Now, that I don’t understand—why somebody misunderstanding emptiness would make them abandon the thought of enlightenment and seek personal liberation instead. Because, you have to realize the same emptiness to attain arhatship. That’s why I don’t understand what he’s saying here.

When they then effectively abandon the Mahayana and strive for individual liberation, the transgression is accomplished, for their motivation has fallen from the superior to an intermediate level. This transgression supposes that we have not made an effort to assess the student’s readiness to hear an explanation of emptiness.

Let me stop before we get into this part, because the following part is something that makes a lot of sense.

The way I’ve usually heard this one described is the person doesn’t have to be somebody who is following the Mahayana and has taken the bodhisattva vow. It can be any old person. But as he’s saying here:

The transgression supposes that we have not made an effort to assess the student’s readiness to hear an explanation of emptiness. If we take the trouble to evaluate their suitability and mistakenly conclude that they are apt, even if they are shocked by the topic to the extent that they give up their aspiration to Buddhahood and follow the hearer’s vehicle, the transgression is incomplete. Although we have not succeeded, we have tried our best to assess the student’s abilities.

When the above conditions are fulfilled, teaching emptiness to those who are unprepared constitutes a major transgression of the bodhisattva vows despite the fact that emptiness is the ultimate mode of existence of all phenomena and that understanding it is the unique door to liberation from samsara. We must conclude, therefore, that it is not because something is true that it is necessary or even right to explain it to anyone who crosses our path.

I want to come back to that point. The way I’ve always heard this explained before is, it can be just any old person, but we don’t check that person’s capabilities. So, it doesn’t have to be someone with a bodhisattva vow or Mahayana, it can be Joe Blow or whoever just walks in off the street. But we don’t assess that person’s readiness to hear teachings on emptiness, and we teach them. And because emptiness is such a delicate subject, they misunderstand it as many people do. The lower schools all misunderstand it and think that emptiness means nothing whatsoever exists.

Somebody comes in off the street to the Dharma center, and you teach emptiness. “When you look in this you can’t find a clock. When you look in here, you can’t find a real cup. When you look in here you can’t find a real person, yourself,” and then that person gets the wrong idea. “Oh, nothing whatsoever exists! If nothing whatsoever exists, then I can do anything I want because cause and effect doesn’t exist. Nothing exists. So, there are no effects of my actions, and everything is just make-believe. As long as I think it, that’s the only thing that gives it some reality and, in fact, nothing really exists.”

It’s falling to that nihilistic state, which is very dangerous. The person is very apt to not take care with observing karma and its effects, which is a danger for them. They are prone to commit a lot of negativities because they think, “Well, nothing exists, so it doesn’t matter what I do.” It can be anybody. It’s really emphasizing the point that we have to assess somebody’s suitability to hear a teaching. Just because we know something, and just because a Dharma teaching is true, that doesn’t mean it’s good to tell it to everybody who we come across.

This is something to really think about. Sometimes in our enthusiasm to share the Dharma with people, we teach them the Dharma, but they’re not ready to hear certain things. They get the wrong idea, and it really turns them away from the Dharma. Here, the specific instance is emptiness, because misunderstanding that leads to this nihilistic view and unethical actions. It could be any aspect of the Dharma. We’re just so over-exuberant and want to tell everybody that we’re not sensitive to what exactly that person needs to hear.

Or sometimes we might be even a little puffed up with ourselves. I call it the “chai shop guru syndrome.” You learn a little bit of Dharma, and now you’re going to become the guru at the tea shop. This happens all the time in India and Nepal. Somebody learns a little bit of Dharma, and then they sit and teach the little bit they learned. Whether they understood it correctly or incorrectly doesn’t matter. They’re so full of exuberance to talk about it that they talk about it in the tea shops, without considering do they know it well enough. Or in this instance of this precept, they teach it without considering is it skillful to teach that to this person? Is the person going to understand things correctly and get the right idea?

So, it’s really emphasizing this one to assess people and look at their training. Especially before teaching emptiness; they always say that you teach about conventional truth first before teaching the ultimate truth. The whole thing about conventional truth is causality: dependent arising, karma and its effects. People always have to learn that before they get teachings on emptiness. You see some people, it’s like, “Forget karma and its effects, that sounds like Sunday school; I want Dzogchen Mahamudra. I want to go into the bliss of wisdom and emptiness and lose myself there,” but the people haven’t understood really well about karma and its effects yet. It becomes confusing for them when they start to think about emptiness, because they aren’t yet grounded enough in a proper understanding of just conventional functioning.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Okay. You were describing the situation you were in. Somebody who is brand new came, and they were grieving the loss of their child, saying “How did this happen? What’s the Buddhist explanation for why it happened?” And yet, you don’t want to get into the whole thing about karma, because they’re brand new off the street. I’ll tell you a story. Do you remember when the flight that went down over Lockerbie? 803? Yes, so, the flight that went down over Lockerbie had a lot of students from a university—was it Syracuse or Rochester? It was a Pan Am flight, remember? This was many years ago, like 1989 or something. I happened to go to that school, and I was giving a talk. Some people there were grieving the loss of their friends, and they asked, “How do you explain this?” And I made the mistake of talking about karma. It didn’t work. And I subsequently learned a similar lesson when I went to a Jewish group and they said, “How do you explain the holocaust?” You don’t talk about karma. That’s not the skillful approach.

In those situations where people are grieving, they always want to know why. But actually, the answer to that question is not really going to help them. The issue is not why did it happen. That’s always our instantaneous reaction of “Why did it happen,’ as if understanding why would help. Often, understanding why doesn’t help at all. Whether it’s a situation of the “why” meaning the immediate conditions, or “why” meaning the whole karmic thing.

The real thing that people are asking or saying is, “I’m grieving. Can you say something to me that will help me alleviate my grief?” They’re saying, “Why did this happen?” But really, what they’re saying is, “Can you help alleviate my grief?” That’s the real question. I think it’s much more skillful, if you tune into what their question really is, to talk about how to alleviate grief. It is a tragedy. It’s the last thing you expect. It’s a shock. Even though on an intellectual level we know things are transient, whenever something happens, we’re always shocked because our mind is clinging to the idea of permanence.

One thing I say to people that I think really helps is, “When we’re separated from somebody that we love, we’re not mourning the past, because we had the past with them. What we’re mourning is the future. We had all these thoughts that that person would be in our future with us. It’s turning out that the future we anticipated is not going to be. So, we’re actually mourning something that hasn’t even happened yet.” And then they go, “Oh, yes, I’m mourning something that hasn’t even happened. I’m mourning something because of my expectation.” And then I say, “Look back in the past and think about the benefit you received from knowing that person. What you shared with that person. Rejoice that they were in your life for as long as they were.”

“Because we know that everything is transient, we know everything is under the influence of causes and conditions and that separation is inevitable. Rejoice for as long as that person was in your life. Wasn’t that wonderful, that you shared what you were able to share? And you loved each other, and you learned from each other, and so many good things happened. And so, just rejoice that you had that. Take the love and everything you gained from knowing that person, or those people, into the future with you. Share that love with other people that you meet in the future.”

That gives people who are grieving a way to think about the situation and a way to transform the loss into getting in touch with the fact that their heart can be full of love for that person. They can take that love into the future and share it with other people. I find really talking to what their needs are in that situation is much more skillful and much more effective than going on a long discourse about karma, and why suffering things happen to good people because in the past they created negative actions. They don’t want to hear that their loved one created a negative action in their past life, you know? That’s not on their radar. It’s better to talk to where they are at the present.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Sometimes when I’m giving a talk I’ll say, “How many people are beginners?” And I’ll raise my own hand, because I’m a beginner. Otherwise, people don’t like to say they are beginners, when we all are, really. I try and get a sense of the group. Sometimes I may ask somebody beforehand, if I’m going to a specific Dharma center, something of the group. Or you ask people questions. Or you start teaching something that you know everybody can take and handle, that’s not going to damage them in any way. Then you see by the expressions on their face what’s going on. I would not go into a group I don’t know and just start teaching about emptiness. That’s not appropriate. It’s not what people need to hear at the beginning. You could speak about how their mind is the creator of their happiness and suffering, which is actually dealing with the topic of emptiness, but it doesn’t run the risk of somebody misinterpreting things.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Oh, yes. This is talking about somebody giving a teaching on emptiness, somebody explaining emptiness to somebody who is unprepared. It’s not talking about having a discussion about emptiness with a Dharma friend.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes, if you’re discussing something with a Dharma friend, you bring up different ideas and you go back and forth, and this is what they do at the monasteries all the time. And this is how you learn.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Well, you have to see who is in the Dharma group. If it’s Joe who just walked in; he knows nothing about Buddhism.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Oh, yes. It seems like there are teachings that are publicly offered: “Come and get the highest class tantra initiation Friday night. It’s your only opportunity. Come get it. It’s only $99. 99 for you—special price.”

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Even His Holiness is giving things that are open to everybody. Is His Holiness’ first Dharma talk in the lecture series about emptiness?

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): No, it’s about bodhicitta, having a kind heart, using our intelligence, using reasoning to evaluate the teachings. He doesn’t start something off with emptiness. He gives people background. And then when he does teach emptiness, very often it’s at a level where the people who aren’t ready to hear it are not going to understand it anyway because he’s saying, “This is what Nagarjuna said in this text in this verse, and then we compare it to that verse here,” and the newbies are going to go, “Huh? ” But His Holiness always gives background.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes, at most Dharma centers there’s weekly teachings and people can drop in. But then, if you’re teaching that class and somebody brand new drops in, you have to see where you are in the text and what you’re teaching. Very often, if somebody does that on the emptiness section, I’ll say to the person, “You probably won’t understand this and dah-da-dah,” and give some kind of introduction before I teach what I had in mind for the rest of the class. It’s to make sure somebody doesn’t misunderstand.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): You’re talking about a situation where a teacher is showing the nature of the mind to a student. That’s probably not going to be done in a Dharma class with a lot of people around.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): You know, I’m not really well-versed in that. I don’t think I can comment on it. First of all, you have to see if that teacher really is capable of showing students the nature of the mind or not. First of all, you have to check that. Second of all, you have to check the students. And like it’s saying here, if somebody checks a student well and then it winds up that the student misunderstands, you’re not breaking this precept. This precept has to do with just not caring and giving the teaching broadly.

This whole thing about teachers showing people the nature of their mind, it’s talked about sometimes as if it just happens in the Dharma center on Thursday night. You just show up and you’re going to get this transmission and be shown the nature of your mind. I’m not so sure it happens that way; I’m not so sure. Because first of all, Dzogchen is an extremely high practice. You have to do a whole lot of preparation to actually be able to do Dzogchen meditation properly. And I know people just walk in off the streets and they’re getting instruction on it. I don’t know, but if you look at the way the great Dzogchen masters—Longchenpa and so on—have taught, it is so much preparation. And then being shown the nature of the mind is not just you happen to be in the group on Thursday night and “Oh, I happen to be giving the nature of mind today, to 35 people who are here.” It’s not like that. To really have that happen, to have some proximity or some good experience, a teacher is going to know that student very well and will have led them from the beginning of the path.

Because if you look where Dzogchen is in the view of the nine dhyanas, it’s the last one. You have to do the first eight first. I’m talking about to really do it. Nowadays, what a lot of teachers are doing is just planting seeds in people’s minds. We’ll give you this initiation, we’ll give you this thing, you probably won’t understand it anyway, but it plants good seeds in your mind for future rebirth. That’s a way a lot of things are taught now.

Because when you look at the qualifications for that kind of student and then you say, “Do I have those qualifications?” that’s all you have to do to understand what is happening. “This teaching is for a student that has this, this, this, this and this, trained in this and this, and has some sense of this and some sense of this and some sense of the other thing. Do I have all of that?” So, let’s go back and create the causes. It’s good to plant the seeds. You plant the seeds, and then in a future lifetime those seeds will ripen, so good to plant the seeds. But in terms of our practice, we need to practice where we’re at.

You have to build the foundation before you build the roof. Otherwise, like we had here, the meditation hall was up in the air, remember? We had the walls and the roof, and we brought them over, but it couldn’t be used because there was no foundation. You build a good foundation, then you can have firm walls; then when you put the roof up, it stays up and it doesn’t leak, and it doesn’t fall down.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Well, you know what I’m going to say. He was reading a book on something about the new American Buddhism or something. I haven’t seen that book yet. Somebody was saying that a very popular teacher said that the Tibetan nomads were very unsophisticated whereas westerners are very psychologically sophisticated, so they’re ready for Dzogchen. So, he’s asking me what I think about that. And he’s lived here a year and a half.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): I don’t think I need to comment on that.

For some reason or another if you ask a question and I don’t understand your question properly, please keep asking it until I do. And then second of all, regarding that question that you asked, to ask one teacher what they think of the way other teachers are guiding their students, that’s not really appropriate. It’s great to ask a sincere question about “Here’s this teaching, am I ready to do it?” But don’t ask one person to comment about how somebody else is guiding their students. Because different people are attracted to different students for one reason or another reason, and to ask somebody to make a general comment about what some other teacher is doing is not something that I would want to do. Because I have no idea how somebody is guiding their individual students and what they’re teaching, what the background is and this and that. If you’re asking “Is this something I should practice,” then that’s something I can respond to.

But that’s different than saying, “This teacher is teaching people this and that and the other thing, what do you think about it?” I’m thinking, “Where would that question be coming from? Why would we want to know what this person thinks about what that person is teaching? Why would we want to know that? Is it because we’re thinking of studying that teaching from that teacher and we want to know if we should?” In that case we should ask the question “Here’s somebody who is teaching this. I feel drawn to study it. Do you recommend that I do?” That’s the question you’re really asking. Do you get what I’m saying? But the question “What do you think of so and so teaching this and that?” what’s the real question behind that? There’s another question behind that, not the question that’s being asked. At least, that’s what it feels like to me. So, maybe it might be good to get in touch with what is the real question that you’re trying to ask.

Because what I think about how somebody else guides their students is who cares? Who cares? Why is that valuable information? Does it help that student? Does it help that teacher? Does it help the person who is asking it? For me to comment about somebody else, how they are guiding their students when I don’t really know, is not for me to say. And it’s not information that I think would be valuable to anybody in their practice. I think, when we think things like that, we should ask ourselves, “What am I really trying to ask?” and then ask what we’re really trying to ask. What it is we really want to know that would actually be of benefit to us in our practice?

It’s kind of like how you see in India, the chai shop gurus, people are talking about what level of the path their teachers have realized. “This teacher is an incarnation of so and so, and that one is an incarnation of so and so.” “No, you’ve got it all wrong, this one is an incarnation of this, that one is an incarnation of that. Their incarnation lineage goes back in here, and so then the way they teach, I’m sure they’ve realized this level and that level and the other level.” And I wonder, what use it that? What use is that?

You might say, well, it develops faith if you say, “So and so is the incarnation of so and so.” It might help develop faith a little bit but to just say, “So and so is an incarnation of so and so,” that itself doesn’t really develop faith. You have to see how the person is acting and see if their actions are something that increases faith in you. It’s not just some title or rumor that they are this or that, or they have realized this and that. You have to look at what are they teaching, and how are they behaving, and how do they treat people? Then, the most important thing is not what level they’re at, or who they’re the incarnation of, but “I’m the incarnation of somebody who just got out of the hell realm, and I have a precious human life, and I better not waste it.”

You’re laughing, but this is true, isn’t it? That’s the important thing to know. I just got out of the hell realm. I have a precious human life. It’s important for me to use it wisely. It doesn’t matter what level they’ve attained and who they’re the incarnation of. What matters is: “The teaching I’m getting, does it correspond to the general Buddhist teaching? Am I understanding that teaching correctly? How do I put that teaching into practice?” That’s what’s important. “Oh, this one’s a Rinpoche who was recognized at this age, and that one is a this, an incarnation of so and so”: that might help develop some faith, but sometimes all these people with these names and titles don’t act in ways that develop faith, and then you get more confused.

There’s something called “the four reliances.” I should talk about that. That really shows what’s important to understand. Remind me, and I’ll talk about that.

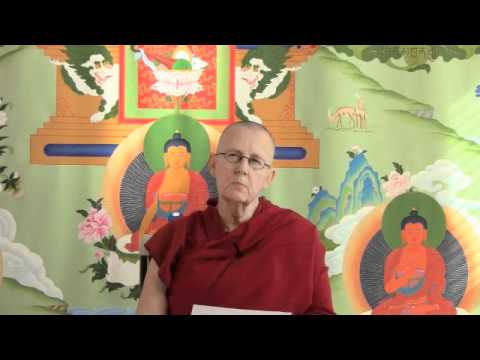

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.