Attributes of true dukkha: Empty

Part of a series of short talks on the 16 attributes of the four truths of the aryas given during the 2017 winter retreat at Sravasti Abbey.

- Emptiness according to the view common to all Buddhist schools

- The definition of an impermanent, unitary, and independent self

- How this view is an acquired view

- Using reasoning to check out the views we were raised with

To continue with the 16 attributes of the four truths, we talked about impermanence and we talked about dukkha, which is commonly translated as suffering, but that’s a very bad translation. The third attribute is “empty.” The syllogism that goes with it is,

The five aggregates are empty because they are not a permanent, unitary, independent self.

This is according to a view that’s in common with all the different tenet systems. The Prasangika alone would define “emptiness” differently, as the lack of inherent existence. But here, because it’s something in common with all the tenet systems, it’s that the aggregates are empty of being a permanent, unitary, independent self. That kind of self is the one that was asserted as the “atman” by the non-Buddhists at the time when the Buddha lived, and very closely resembles the idea of a soul that exists in Christianity and other religions, that there’s some permanent, unitary, independent soul. The arguments against there being that kind of self or soul can also be used to disprove a “creator,” because a creator would be permanent, and unitary, and independent.

Now we have to look at what those three qualities mean. Permanent means, as we figured out before, not changing moment to moment. Something that is permanent can’t change. It means that it’s not produced by causes and it doesn’t produce an effect. That alone, if the person were permanent like that, then we couldn’t do anything because we’d be frozen. We would not be able to have any effects, we could not change. But every single thing we do, we’re changing. Every single moment in time, we’re changing. A permanent kind of thing that is the person just doesn’t work.

Partless, or unitary, means something that’s monolithic, it doesn’t depend on different parts. But the self does depend on the body, it depends on the mind. It is designated in dependence on a collection of different parts. But this kind of unitary self is just one thing. No parts.

Then “independent.” Independent has different meanings in different situations. Here, usually, independent means independent of causes and conditions. Again, not arising due to causes and conditions, not producing any kind of effect. Sometimes “independent” here is glossed to mean independent of the aggregates, so some kind of person that’s independent of the aggregates. But something that’s independent of causes and conditions would be independent of the aggregates, because the aggregates are dependent on causes and conditions and they change all the time. So it kind of boils down to the same thing.

This is an acquired view. This one is not an innate one, it’s one that’s learned by incorrect philosophies and psychologies. Did you learn at some time as a child, or as an adult, that there’s some thing that is just permanently who you are? Permanently, unchangingly, lasts forever, no parts, no causes, no effects, independent from your body and mind, that is just who you are. Did you learn that kind of idea as a kid? That’s this one. It’s an acquired afflictive view, meaning that it’s something that we learned through wrong philosophies or ideologies. If you hold that kind of image of a permanent self, if you really hold that and you want to be consistent with holding that, then it’s…. I mean, it doesn’t work because then you can’t change. And we are changing so our experience disproves it. But on a soteriological level it means we could never become liberated, because something that’s a permanent self can never change, can never be liberated. That’s it. Always polluted, always stuck in samsara, that’s it. You have to say that if you’re going to be consistent with having a permanent self.

It’s an interesting thing to look at because many of us learned that kind of thing when we were children. Similarly, we may have learned about a creator who is permanent, monolithic, doesn’t depend on causes and conditions. Nothing caused the creator. The creator always was. Creator always will be. Does not change. If a creator cannot change, and is permanent, then that creator cannot produce anything. Because as soon as production is asserted, there’s change. Every time you make something, something has to change from what it was to what it will be. When you make a table, the wood is changing from just being wood to being a table. But the person who’s making it, the creator of the table, also has to change because they have to do things to make this thing come into being. In the same way, a permanent creator would have to change in order to create the world, the sentient beings, the environment. Something that is permanent, something that is independent of causes and conditions, cannot change, cannot produce. Similarly, something that’s monolithic, not dependent on a collection of parts, just one monolithic, unchanging thing. What can that do? Nothing.

You really have to use reasoning to check out some of the views that we grew up with. And many people find that they practice the Dharma for a while, and they really appreciate Dharma philosophy, and emptiness, and like this, but then something happens and they want to pray to God. Just because you learned it when you were a kid, “I want to pray to God.” But what’s your idea of God? Is it permanent, monolithic, independent? If so, such a being cannot do anything, and praying is useless. If such a being can do something, then it can’t be permanent. It can’t be independent of causes and conditions. It’s got to have parts.

We really have to think about this. Sometimes we have this old baggage from pre-Buddhist days hanging around in our mind, so we really have to use this kind of reasoning to think about it.

Similarly, for people who say there was one unitary substance, unitary cosmic substance, out of which everything was created. Well, if it’s one thing, and it’s unitary, then it can’t have parts that become different objects. If it’s permanent it can’t change to become different things.

It’s so interesting, most societies have some idea of some permanent something something that is beyond everything, yet also creates. But when you use reasoning you can’t prove that kind of thing. In fact, you prove the opposite.

Those of us who were studying with Geshe Thabkhe this summer when he was refuting some of the non-Buddhist schools in chapters 9-12 of Aryadeva’s “400 Stanzas,” some of the schools have this view that the self is basically permanent, but part of it is impermanent. And if we look, sometimes we think that way. Yes, there’s a permanent soul that’s really me, that’s eternal, that never changes, but there’s also a conventional me that changes, that gets reborn, that changes bodies, changes mental aggregates, that changes over time. But then there’s also a ME that doesn’t change. Aryadeva really refuted that, because how can something be permanent and impermanent at the same time? Because those things are mutually exclusive, they’re contradictory. Something cannot be both. You can’t say, “Yes, there’s this eternal, permanent soul that’s really me, and on a conventional level everything about me changes.”

There’s a lot in this particular one to think about, and to really search our own minds about what did we believe, what were we taught as children? Because sometimes those things that we learned as kids, they kind of linger on in one way or another. And is such a thing possible?

This is just one of those kinds of lingering beliefs. Another one may be that this creator (or something) gives rewards and punishments. And then you conflate that with the Buddhist idea of karma. Which is completely different. Karma doesn’t depend on a creator. We are the creator, we create our own actions. And we experience the results of our actions. There’s no external being who gives rewards and gives punishments. If there were then there could be a rebellion in there. Especially if that being is supposed to be compassionate.

Just look at the things that you learned early on and what you still need to work on and really let go of.

Audience: One of the things that I’ve had to let go of is that I’m inherently flawed, or inherently there’s some sort of original flawed sin that is totally irreparable and you’re screwed.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): That’s another one of them, isn’t it? Original sin. What did I do? I was created flawed. Or I inherited flaw, I inherited wrongness genetically. After this apple fiasco. Then it was implanted in the genes, and just because I’m a product of all these ancestors going back to the two original ones, they got flawed so I inherited it genetically. If you believe that kind of thing then you’re asserting the body and the mind are completely the same. Or that your mind was produced by your parents’ minds, and then they really lost their mind when they had us.

Very interesting. Take out these things and really look at them, it can be quite liberating.

Audience: When I first met the Dharma and I heard a little bit about buddha nature and storehouse consciousness from the Chinese tradition, I really thought those were permanent, unitary, and independent, and it was very comforting for the mind. It took many years for me to see, “Oh, I’ve completely misunderstood.”

VTC: Right. That’s very common, to see the idea of a foundation consciousness, or storehouse consciousness, as like a soul, and in fact, the Buddha says sometimes that he taught that for people who like that kind of idea of a soul as a way that they could kind of hold onto a little… They would be attracted to that idea. But then as they progress they would learn that a foundation consciousness couldn’t be permanent.

But it’s interesting, isn’t it, this idea of there’s something permanent. In Buddhism what is permanent? Emptiness. Nirvana. Those are the ultimates that are permanent, that will never let us down. But things that are conditioned, especially by afflictions and karma, cannot be trusted.

Audience: During this retreat I had one of those experiences where I found myself talking to God. And I never fully believed, but I guess I never fully disbelieved, like deep down. Intellectually I was like “this is not true” but it sort of came out, and I had no idea it was there. So it’s, like, buried deep and it hides. So you really got to like open up and see what comes out. And I think one way you can really get at those deep, underlying beliefs is think about your death. What’s going to go through your mind? Are you suddenly going to start praying? Because I think a lot of people might. But yeah, I was just shocked that was in there and I had no knowledge of it.

VTC: There’s lots of stuff in there that we don’t know about ourselves. That’s why purification, I think, is quite important. It flushes out a lot of that stuff.

Not to criticize people who believe in a creator. Because for some people that view helps them to maintain good ethical conduct. So we don’t go around criticizing other religions when they can benefit other people. When it comes to debating philosophy, yes we can debate philosophy and criticize and point out inconsistencies and everything. But that is very different than criticizing a religion or telling people who have a certain faith, who benefit from that faith, telling them that that’s just craziness. When people are having some doubts then they’re really open and we can talk to them and bring in new ideas.

Audience: Has anybody been able to determine why Buddhism emerged when it did? The point at 2600 years ago, its relevance to emergence of other religious schools of thought…

VTC: Well, the people there had the karma to receive the teachings. As we were talking last night, when people have karma to be benefited, then that karma can ripen, then the buddhas automatically manifest and give the teachings, or do whatever they can to benefit.

Audience: What I struggle with is so much of the content that we read talks about beginningless, so why did it happen then, if it was beginningless?

VTC: Well, why wouldn’t it happen then? Why would it happen then? Because the causes and conditions were coming together for it to happen. You don’t need some type of external creator who all of a sudden decides, “oh, now we’re going to teach this and that.” It’s sentient beings have that karma that’s ripening, and then the buddhas, because of their great compassion, just automatically respond.

The Dharma was also taught before in other universes, other world systems. This isn’t the first world system where the Dharma has existed. There have been previous wheel-turning buddhas in previous universes, infinitely.

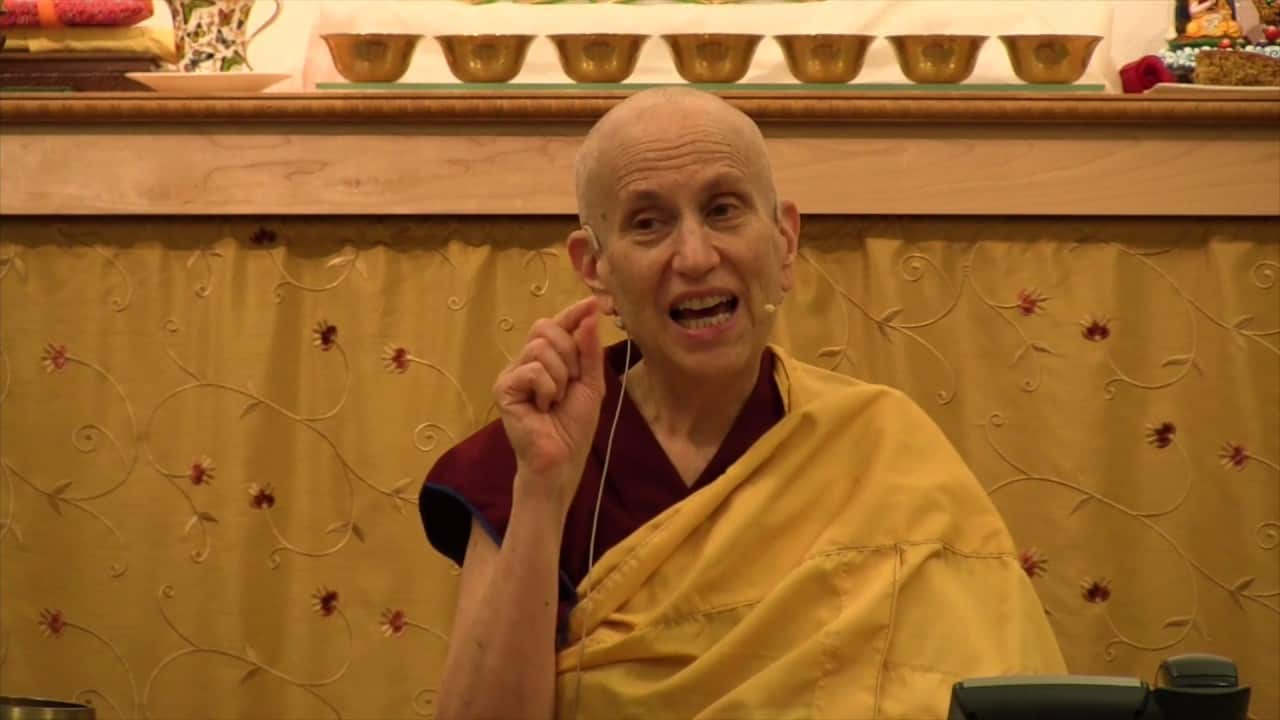

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.