Attributes of true dukkha: Selfless

Part of a series of short talks on the 16 attributes of the four truths of the aryas given during the 2017 winter retreat at Sravasti Abbey.

- Defining a self-sufficient substantially existent person

- The idea of a “controller”: How much control do we really have?

- What can be identified as the controller?

- The Prāsaṅgika Madhyamaka view of “empty” and “selfless”

Last time we were talking about the third attribute of the first truth, true dukkha, and saying that the five are empty because they are not a permanent (or eternal), unitary (or partless), independent self. This is the view common to all the Buddhist schools. This kind of thinking of a permanent, monolithic, independent self is a completely fabricated—intellectually fabricated—conception. It’s not something that’s innate, that we’re born with, but it’s something that we have made up because it feels good. When you’re afraid of death, and you don’t know what’s happening after death, to have this idea that there’s some permanent, monolithic, impenetrable, unchanging (thing) that is really you is very comforting. When you think about it, it’s just this idea of some kind of soul or self, or something like that, that makes you feel, “Okay, my body may decay, who knows what happens to my mind, but something that’s the essence of ME, that never changes, impenetrable, always ME, continues, and it’s not destroyed.” That’s very comforting to people. The problem is that if you apply any bit of logic to it you see that such a person—an I, a soul, a self—cannot possibly exist. That’s the problem.

We human beings are very good. We create all sorts of ideas about many things, but we don’t often apply reasoning to our ideas. “I’m broke, so I think I’ll write a bad check—or a fraudulent check from somebody else’s account. Sounds like a great idea!” We don’t think logically, reasonably of what the result is going to be. It’s this kind of intellectually made up thing.

The fourth attribute, the syllogism goes,

The five aggregates are selfless because they are not a self-sufficient, substantially existent I or person.

Again, this is the view common to all the Buddhist schools that everybody would agree on. Different from this permanent, unitary, independent self, the self-sufficient, substantially existent one can change. It’s influenced by causes and conditions, and it’s this feeling like there’s something in me, maybe some aspect of my mind, that is in control of the whole shebang. This is our control-freak self. It has acquired and innate forms. But it’s the one that feels, “Oh, I can control my body, I can control my mind. I’m in control here. Look, I can control my body. I choose to move my hand. I’m in control here. There’s a person that’s in control.” I—maybe some aspect of my mind,—says, “Move your hand,” and the hand moves. Look, I’m in control. And I say, “Okay, let’s think about loving kindness.” So you think about loving kindness. Oh look, I’m in control. I can tell my mind what to think about. Or let’s think about my taxes. I’ve got to sit down and do my taxes. (Not in the middle of retreat.) And so look, I’m in control. I make my body sit down and I make my mind focus on the taxes.See, there’s a ME that’s in control. Right?

The problem with this one is, how much control do we have? Can we prevent our body from getting old and sick and dying? Forget it. Can we make our mind concentrate? It feels like we should (be able to). I hate to admit it, it’s an excuse—but it doesn’t feel like an excuse, it feels like it’s quite reasonable—why my concentration is not so good. It’s because I don’t really try hard enough. If I just kind of sat there and really tried, for sure I could have single-pointed concentration in that very session. It’s just I’m a little bit lazy, so I don’t try. But I could make my mind do it.

Wrong again. We soon notice that, don’t we? We may have great aspiration, but we can’t make our mind do anything for too long when it doesn’t want to.

Also, the problem with asserting this kind of self or “I” is what are you going to identify it with? You have to find something that is it, so what is a self-sufficient substantially existent I? Is it our body? Well, our body can’t issue directions for things to happen. Is it our mind? Well, it seems like our mind can control things (except it can’t). But also, again, which state of mind is it? And we can’t find one single consciousness that can alone perform that role. So we say it’s “selfless.” “Selfless” means there isn’t that kind of self.

That’s what all the Buddhist systems can agree on for those last two, for empty and selfless. In terms of the Prāsaṅgika Madhyamaka school, both empty and selfless would have the same syllogism, saying,

The five aggregates are empty and selfless because of not being an inherently existent person.

There the object of negation is an inherently existent person, which is different than either a permanent, monolithic, independent person or a self-sufficient substantially existent person. An inherently existent person is not dependent on any other factors whatsoever, and it also seems to be somewhere in our body and mind, associated with our body and mind but also separate from it. Something that, again, exists under its own power. it’s a very subtle level of grasping that apprehends the self as existing that way. To notice that and to see the difference between that and the self-sufficient substantially existent one, I think, requires a lot of deep understanding and strong mindfulness and concentration, because the inherently existent “I” kind of easily hides. As soon as you think you’ve got it, it’s actually showing itself as being the body, or showing itself as being the mind. We can never quite catch it as something that is associated with the body and mind yet separate from it. It’s very difficult to catch, and it’s also something that’s totally independent of everything else. It just sets itself up.

I think sometimes—this is my guess, I don’t know—when your mind’s a little bit quiet and you just think, “I”—or you think your name—and this feeling of something just kind of [perks up]. Maybe that’s it. I’m not sure. It’s not this kind of gross thing like “I’m in control.” It’s much more subtle than that. They say that you can see it when somebody accuses you of something you didn’t do. Or even something that you did do, but especially something that you didn’t do. But I’ve heard one geshe say that actually that’s the self-sufficient one that pops up in that circumstance. But then I asked another geshe and he said, well, just try and see the inherently existent one, because if you get that one then you’ve got all the others. And what I found very interesting is in Tsongkhapa’s Lamrim Chenmo there’s no mention of a self-sufficient substantially existent self. And he wrote that text prior to his middle lamrim, and prior to (Gongpa Rabsel) Illumination of the Thought of the Buddha. And in those two texts he talks about a self-sufficient substantially existent “I.” So, I don’t really know. I’m still trying to figure this one out, too. But that’s a little bit about what I’ve thought about so far.

For the Prasangika, they would assert that kind of emptiness (or selflessness) as the third and fourth attribute of the first truth. They would also assert that kind of emptiness (and selflessness) not just for the person but for all phenomena. Everything. Not just that there’s no inherently existent “I” but that there are no inherently existent aggregates (or whatever). And in thinking about this more… Because the five aggregates are always the example used in it, I wonder if the Prasangika would really redo those and say, “The I is empty because of not being inherently existent,” and put the “I” there in terms of the aggregates. And do a second syllogism: “The aggregates (or all other phenomena, which usually implies the aggregates… There’s more phenomena besides the aggregates) are empty (or selfless) because of not being inherently existent. Because the Prasangika assert a selflessness not only of the person (which means our “I”) but also of all other phenomena. Other people’s “I”s and the aggregates, and the chair, and the table, and empty space, and everything else.

There are definitely some differences here between the schools. But, that’s the big troublemaker. As Nagarjuna says, if we can’t really hold in mind the first two [attributes] (especially the second), then it’s going to be very difficult to hold in mind the last two. Because realizing the first two (impermanence and dukkha), and then also realizing the foulness of the body, those things come prior to realizing emptiness and selflessness. And yet, Nagarjuna says, the foulness of the body, how long can you hold onto that understanding? A minute or two? But as soon as you get up from meditation and think of lunch the body no longer appears foul to you. If we can’t hold onto those understandings, which are much easier, then to think we can just dive right in and realize emptiness immediately is a little bit over our reach.

This is important to contemplate, whether it’s over our reach or not, and it’s very helpful, as you’re going around all day, to sometimes ask yourself the question: If you’re walking, “Why do I say ‘I’m walking’?” Or if you’re thinking about something, “Why do I say ‘I’m thinking’?” “Why do I say ‘I’m daydreaming’?” Or another way to put it is, “Who is daydreaming?” “I’m having this fantastic distraction in my meditation, I don’t want the bell to ring. Who is having this distraction? Who’s dreaming about buddha-boy? Who is unable to concentrate?” “I can’t concentrate at all.” Who? It’s a very good question. Who is unable to concentrate? “I am, I can’t.” Who? What’s that “I” that can’t concentrate? Look for it. “I’m so tired I want to go to sleep. Where’s my blankie?” Who’s so tired? We should ask the kitties who’s sleeping all day. It’s quite interesting to just ask yourself. “Those people don’t appreciate ME.” Who’s the person they don’t appreciate? This is a really good one. “They don’t love me.” Who is it they don’t love? Who’s that “I” that’s unloved? Or unnoticed. Or unrecognized. Who should be Maheshvara, but nobody sees that. Nobody sees my potential. [laughter] Just investigate that, it’s very, very interesting. Very interesting. That’s a kind of practical way you can put this to use in your life.

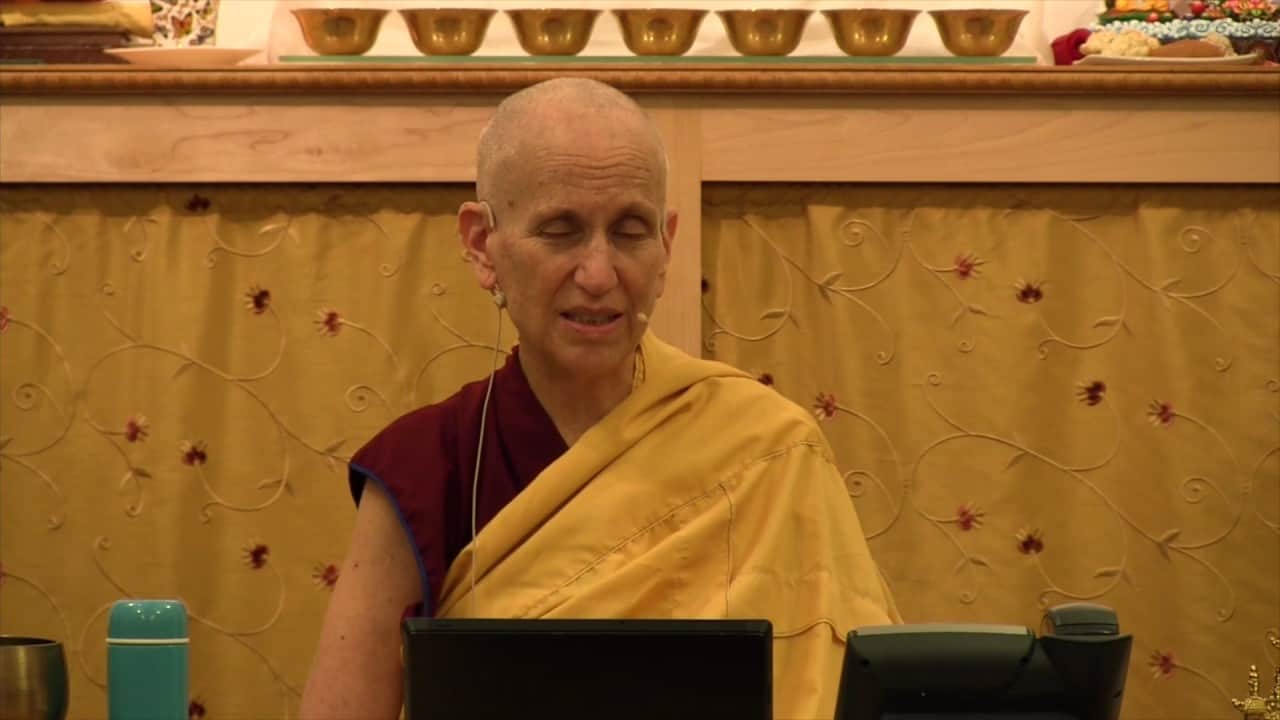

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.