Bodhisattva ethical restraints: Auxiliary vows 30-33

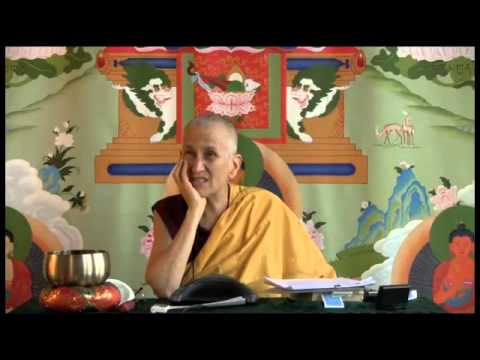

Part of a series of talks on the bodhisattva ethical restraints given at Sravasti Abbey in 2012.

- Auxiliary vows 27-34 are to eliminate obstacles to the far-reaching practice of wisdom. Abandon:

-

30. Beginning to favor and take delight in the treatises of non-Buddhists although studying them for a good reason.

-

31. Abandoning any part of the Mahayana by thinking it is uninteresting or unpleasant.

-

32. Praising yourself or belittling others because of pride, anger, and so on.

-

33. Not going to Dharma gatherings or teachings.

The bodhisattva path is the path that depends on cultivating compassion, altruism and especially wisdom. Those are all traits that we have in us right now to a small degree. What we want to do is fertilize those seeds, water them and help them to grow so that they become the actual manifest minds of bodhisattvas and then buddhas. And we want not only to help those seeds grow within our self but in each other as well.

So, it’s not just, “I want to get enlightened for the benefit of all sentient beings”—again the big ME—but it’s “We want to get enlightened for the benefit of all sentient beings.” In our actions we’re really looking out for others and trying to help them cultivate their good qualities and to water the seeds of virtue in them. This is quite a full-time job, but it’s a wonderful job, and it involves looking at ourselves and looking at others with whole new eyes—the eyes of nurturing what is good in ourselves and others. With that kind of motivation, aspiring for full enlightenment, we’ll listen to instructions on the bodhisattva precepts.

Watering seeds in others

It came up this morning in our meeting about taking care of our own needs. If we don’t take care of our own needs, we don’t have a happy mind, and when we don’t have a happy mind it becomes very difficult to practice. It’s important to take care of our own needs because it helps us water the seed of virtue within ourselves, but it’s also important to keep looking beyond our own needs and really care about the needs of others so that we can water the seeds of virtue in others. We’re not just being concerned with “My merit, how I can accumulate merit? How I can learn the Dharma? How I can practice? How my seeds of virtue can get watered?” But it’s really thinking how can we also water the seeds of good qualities and the seeds of virtue in the people around us.

Because we know that when we have manifest ignorance, anger and attachment, already our own seeds of afflictions have been watered. But then we usually speak and behave in ways that bring about the ignorance, anger and attachment of whoever is around us at that moment. So, it’s important to continually ask ourselves, “Do I really care about the needs of others? Do I care about the welfare of others? Do I care about the enlightenment of others? And if I do, how can I water their good seeds and help them along the path?” With an insect it might be reciting a mantra and blowing on it. With one of our fellow students it might be discussing the Dharma or helping each other when we get stuck. And with other people you never know the seeds of virtue that you’re going to be able to water in somebody’s mind if you pay attention.

Last week when I was in the dentist’s office, a volunteer just brought up something that had been really troubling her in her practice and right there in the dentist’s office we talked about it. I just needed to give a simple explanation and she said, “Oh, that’s true, that’s really true.” And then it was gone and I was going, “Oh, my goodness, imagine what you can do waiting to have your teeth cleaned!” [laughter] You never know where the opportunity is going to pop up before you to do something that’s beneficial. So, it’s important to have that kind of attitude.

30. Taking Pleasure in Applying Yourself to the Non-Buddhist Treatises

The new one is thirty. It says, “Taking pleasure in applying yourself to the non-Buddhist treatises.” The previous one was applying yourself excessively to non-Buddhist treatises and this one is really getting into it so that your mind is beginning to change views and say, “Oh, these non-Buddhist treatises, they really have a good point here.” I remember in Dharmsala, when Geshe Sonam Rinchen would teach us things like the Samkhyas’ philosophy—because you have to learn a little bit about it to refute it—we would scratch our head and say, “Who in the world would ever believe this stuff?” And he said, “Well, if one of those panditas came here and explained it to you, you would believe it.” In other words, don’t be so arrogant that you think you won’t fall for something. Sometimes we have to learn non-Buddhist things so we know what people in the world are thinking, so we know what their ideas are, so we can have discussions with them and share ideas with them and have an interchange and present them with new ideas to consider. But in the process of learning what other peoples’ ideas are we don’t want to get so fascinated with them that we forget the path that we’re already on.

I think I gave the example last time about how at one point in Buddhism in the West people started thinking, “Oh, but Buddhism doesn’t really do everything, we need psychology.” And all of a sudden all these Buddhist practitioners are reading all these psychology books, going to psychology courses and psychologizing on their meditation cushion. I think psychology is very helpful but I think in a way people, at least during that time, may have gotten too interested in it and not realized the difference between psychology and Buddhism; and what can psychology offer you and how does that differ from what Buddhism offers you; that they aren’t exactly the same and you use the two different things for different needs, even though there’s some overlap between them.

Or it could get into, if you really start reading science books, learning about the universe here and this and that and the other, you get so interested and so fascinated in it and you don’t have any time for your Dharma study. Then you start thinking, “Oh well.” Some of the scientific ideas really jive with Buddhist concepts, some of them don’t. And some of them, the scientists themselves have two different ideas so it’s something to be interested in but to really always check our view.

For example, some scientists would say there isn’t an objective world, the whole thing with the wave and the particle, so they may say there is no objective reality, that what we perceive depends on the perceiver. That would really jive very much with Buddhism. But then you’re going to meet other scientists who say, “No, there’s an objective reality out there.” And some scientists similarly will say, “There are the smallest particles, we just haven’t found them,” and other scientists may say, “No, there aren’t any smallest particles.” You find a difference; some of those ideas tend more toward the Buddhist view, at least the Madhyamaka view, some tend towards the view of the Vaibhashikas or the Sautrantikas. So we can’t say science is one unilateral, monolithic field and neither is Buddhism. There’s a lot of diversity of opinions.

Dagpo Rinpoche says:

This misdeed, The Great Way calls ‘Taking pleasure in applying oneself to the non-Buddhist treatises,’ which means that we should not relish reading or studying non-Buddhist philosophies but consider it as we do taking medicine, something unpleasant but necessary.

I think that’s a little harsh; I think there are some interesting we can learn in other things.

By enjoying it too much and rejoicing in it, we commit a secondary misdeed associated with afflictions because we are under the influence of attachment. We should not acquaint ourselves with non-Buddhist philosophies and views for our personal enjoyment, but because it is necessary to benefit living beings. As we pursue our studies, we must keep the purpose of it in mind, we are learning about them to better help others.

I think that’s really important that Buddhists don’t just study Buddhism. Especially if you’re on the bodhisattva path, you have to learn a whole wide activity, but whether you’re learning accounting or construction or the theories of another faith or philosophy, it’s important to always have very clear in our mind our motivation for doing it so we don’t get confused. Otherwise, you might start thinking, “Oh, accounting is so interesting.” Maybe for you it’s nursing, not accounting. “This is so interesting, maybe I should really do that.” And then we get off track.

The last four precepts, one was rejecting the Disciples’ Vehicle, then while you have your own tradition devoting yourself to the Disciples’ Vehicle, then applying yourself excessively to non-Buddhist traditions, then the fourth was taking pleasure in applying yourself to them.

Those four faults, the first represents the decline of an aspect of the ethic of collecting virtue, which is rejecting wrong views.

The first one, the wrong view here, was thinking that it’s totally unnecessary to study the Disciples’ Vehicle. That’s a wrong view. If we transgress that precept we are not rejecting that wrong view, but we’re buying into it.

In the second and third ones—[which are when you have your own tradition directing your mind to the Disciples’ Vehicle and also excessively studying the non-Buddhists things]—we’re also transgressing the ethic of collecting virtue, the aspect of it of studying and reflecting.

It’s because we’re not putting our energy in the suitable directions for what we’re studying and reflecting. And then the commentaries don’t specify with which precept the fourth misdeed is compatible.

Remember, there are the three types of ethical conduct; what are they?

Audience: Not doing harmful actions, practicing virtue, and benefiting other beings.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Right. Abandoning harmful actions, create virtue and benefiting sentient beings.

31. Rejecting the Mahayana

Number thirty-one is “Rejecting the Mahayana,” and he says, “Next we have four misdeeds in relation to greater objects.” Here greater objects meaning the Mahayana, the universal vehicle.

[The first of which is] rejecting the objects of wisdom. It consists of denying that the collection of Mahayana scriptures is authentic and as such, is a misdeed associated with afflictions.

Remember we had one of the root precepts which was saying that the Mahayana scriptures are not the teaching of the Buddha. This initially, when you read it, might lead to thinking, “Oh, the Mahayana scriptures aren’t authentic.” It sounds like the same thing but pay attention, it is different here. Here’s where the difference comes in.

The Great Vehicle’s teachings are too vast for our narrow minds and as a result we question their validity. We distrust the deep doctrine of emptiness, the profound aspect of the path, and the extraordinary qualities of the buddhas and bodhisattvas, an example of the vast aspect of the path.

Here it’s because we don’t understand emptiness or we don’t understand bodhicitta, so we begin to have a lot of doubts and distrust and this kind of skepticism and disbelief that says, “These teachings are just make-believe, this is crazy stuff, what do you mean everything is empty of true existence? This is here, I see it, I touch it, I feel it, it’s not empty.” People hear the buddhist idea of bodhicitta and exchanging self for others and really caring for others as much, if not more, than caring for ourselves and they say, “Impossible! Ridiculous! We are biologically programmed to be selfish because we want to get our own genes in the pool and that’s the only way, we can’t overcome that. All this Mahayana talk, these sutras are not authentic, they’re just babble.” That’s one way that it can happen.

Do you think we’re inherently selfish, that our body’s programmed us that way and there’s no alternative to it? It would really take a lot of joy out of life if you felt that way, wouldn’t it?

Audience: It would justify a lot of really bad behavior too.

VTC: Yes, it sure does.

Audience: It seems like a person that’s celibate disproves that whole idea. Otherwise they would not be able to be celibate; they couldn’t do it.

VTC: Yes right, that’s true. That’s why some people think we’re nuts. [laughter]

One weekend when I taught in San Francisco, somebody who studied evolutionary biology commented that when somebody harms us, we are programmed by our genes to get angry and retaliate and protect ourselves from harm. She was saying this is just common sense to keep ourselves alive, and it’s genetically in our body. When you first hear that, it sounds right, doesn’t it? Because you look around and this is what everybody thinks. I was saying, “But we actually have a choice of emotions. We aren’t emotionally programmed so that if this happens, we must feel this.” I said, “We do have a choice in what we feel.”

She was saying that there’s been a scientific study that when we walk down the street if people don’t look at us our mood goes down. And if we’re in a meeting and people ignore us, in other words, if we’re not recognized just in casual ways by eye contact or a greeting—very simple ways—then our mood goes down, our self-esteem goes down, and we get kind of depressed. I guess there’s been some studies showing this. And she said, “This is just how we are. We’re programmed. This is evolutionary biology.” And I said, “No, we do have a choice. Look at His Holiness, he’s trained his mind deliberately, conscientiously, continuously, so when he sees a stranger on the street his reaction is not ‘Is this person noticing that I exist?’ and letting that determine his mood, but his whole way of relating to the stranger on the street is, ‘Here’s another sentient being who has been kind to me and how can I be of benefit?’”

And I said, “How we relate to somebody, what perspective we carry with us determines how we experience a situation.” Many people may bring the perspective of “Notice me” but not everybody does, and we can certainly train our mind to have a different perspective. She was going, “Oh.” It’s true, if you think about it. I was saying “If we just live on automatic and we’re not aware of what we’re feeling and thinking, then that’s very true, most people will react by feeling kind of down. But we have a choice and we can be more aware and mindful and we can deliberately train our mind in a different way. This is not all pre-programmed.”

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: But I think sometimes they may say the genes program us.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, I think they mean condition but it sounds like a narrow condition.

There are four specific ways of rejecting the Mahayana. We can refute the possibility of achieving higher insight, such as the wisdom understanding selflessness by practicing these teachings.

That’s one way of refuting the Mahayana: thinking, “It’s impossible to develop the wisdom realizing selflessness because selflessness is a bunch of quackery,” or “There’s no possibility to change our mind,” or whatever reason we have. It’s holding that kind of idea.

Secondly, we may deny that they allow us to increase our merit.

In other words, it’s thinking that the Mahayana teachings don’t enable us to increase our merit and create virtue, or maybe just saying, “It’s impossible.” Some people say, “Exchange yourself for other? Impossible. That’s la-la-land.”

Thirdly, we might declare that it was not Lord Buddha, but lesser masters who taught the Mahayana scriptures. And finally, we can assert that they are useless for living beings.

Audience: What’s the fourth one?

VTC: Saying that the Mahayana teachings are useless for living beings. That’s like saying love, compassion and altruism are useless for living beings.

If we find ourselves doubting the Great Vehicle teachings we should think that perhaps we lack the wisdom to fathom them but that the Tathāgatas perceive all phenomena directly and it is on that basis that they gave them. We could say to ourselves, ‘With my limited faculties, who am I to judge? Since the buddhas are omniscient, their perceptions are infallible, and all their teachings must be so as well.’

For some people, that way of thinking works and for some people it drives them nuts. Because some people may say, “Okay yes, the Buddha’s omniscient, sure, I don’t understand this, but I believe that, and so I can give it some space and leeway.” And other people are saying, “Look, I don’t really understand who the Buddha is, I’m not quite sure the Buddha exists so I’m not so sure that I can just sign off. I have to really understand this and investigate it and make up my own mind.” So this way of thinking may or may not work for everybody.

Although we may not succeed in feeling faith in all aspects of the Mahayana teachings, if we can manage not to deny them we will avoid this misdeed.

That’s one thing—maybe we don’t have faith in all the teachings but at least we don’t have to reject them. I think that’s a very good point; we may not believe it but we don’t push it away either. It’s like when people say to me, “What’s the difference between Buddhism and Christianity?” Or, “Do Buddhism and Christianity lead to the same goal?” How are you supposed to answer that question? I say, “I haven’t even actualized the end of the path I’m following, how can I even say where the path I’m not following leads to? That would be pretty presumptuous on my part, I have no idea. In the same way to reject something without a thorough understanding of it doesn’t make any sense.

Certainly I can debate different ideas within Christianity, based on logic and reason and come to a conclusion about that, but I have no idea what the Christian mystics practiced and what they realized. There’s no reason for me to comment on that at all. I love when people try and ask me these questions and make me give an opinion about something that how can I possibly have an opinion about. Usually my opinion factory is quite good and I think if you got me maybe off camera, I might give you a few opinions but if I’m really serious, I’m thinking well about things, I can’t say.

Generally, it may be difficult for beginners on the path to aspire to every aspect of Buddhist teaching, but they should maintain a neutral attitude toward the parts that do not appeal to them.

This lady who was asking the question on evolutionary biology drove me home after the talk on Sunday and she was saying, “I just have doubts about rebirth and these deities but I know the practice works.” It was interesting, similar to what you were saying. And she was just getting really stuck, “I really like Buddhism and I feel so drawn to Tibetan Buddhism but I just can’t accept some of this stuff.”

I said, “Stop sweating it,” because sometimes our mind gets into “I’ve got to figure it out right away and I’ve got to understand this and got to get it right now.” I said, “Relax, just practice whatever makes sense to you, put that into practice, use that to improve the quality of your life. As you do that and as your mind develops and changes, from time to time you can revisit some of these topics and they may appear differently to you, but you don’t need to figure them all out right now.” And she kind of went, “Oh, okay.”

I think that’s really true, because how many of us understand everything? I don’t know about you, but I don’t. That’s why they say we keep studying, reflecting and meditating all the way until we become buddhas because we don’t understand everything. And it doesn’t mean we’re a flake if we don’t. I think it means we’re honest. When people say, “Oh, I understand it all” it’s like the guys who say they’re enlightened.

32. Praising Yourself and Belittling Others

Thirty-two is “Praising yourself and belittling others.” Now that I’ve explained to you the right way to see everything, unlike all those other people with all their wrong ideas and wrong ways to go about it. [laughter] So, it’s praising yourself and belittling others. Remember this came also as one of the root precepts? But again it’s different, so pay attention here.

This fault is described as inverting the result for the outcome of the correct practice of the Mahayana should be to praise others and depreciate ourselves.

Does that sting a little bit?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Praise others is okay but depreciate myself? I’m really important here, you know? If I praise others it’s to illustrate to other people how wise and compassionate I am and what a good practitioner I am.

Audience: That depreciate myself, what is the difference here?

VTC: Good question. The part that depreciates ourselves and tells ourselves, “I’m incompetent, I’m stupid, I’m unlovable, I’m worthless, I make so many mistakes, I can’t do anything right;” there’s that side of ourselves, but that’s not what we mean by “The result of the Mahayana is to praise others and depreciate ourselves.” Because that way of depreciating ourselves is a very self-centered way. Remember? If I can’t be the best one, I’m the worst one? It’s completely revolving around ourselves and our own deficiencies and how bad we are and “blah, blah.” That’s not what he means here by “The result of a correct Mahayana practice is depreciating ourselves.”

What he means here is that when we think about whose happiness and suffering is important, instead of holding me, me, me, me, me, we say, “Others and then me.” Instead of going into a room, “Here I am, aren’t you pleased?” we really go in the room with, “Who can I be of benefit to here?” That’s what he means. Not depreciate ourselves in a psychologically shameful way, but just releasing that mind that says, “I’m the most important one and everything that happens to me is so crucial and so critical and so earth-shattering.”

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Right, exactly. It has the quality of humility. Being humble and having humility is very different than having low self-esteem. When we disparage ourselves, the result is low self-esteem. When we reduce our importance because we see with a wisdom mind the kindness of others, that kind of humility is not imbued with trashing ourselves and so on and so forth. It has a certain kind of gentleness and resilience to it.

Normally if people don’t treat us the way we think we should be treated, we’re kind of, “Do you know who I am?” But I think that the really great practitioners don’t view the situation like that. They’re not looking at it as, “Oh, here’s all these people, do they know who I am and are they treating me the way I should be treated?” They’re going into the situation of, “Here are kind mother-sentient beings, how can I help them?” What you go into the situation with is going to determine how you experience it, what you perceive, even.

When we praise ourselves and disparage others out of pride or vanity, the misdeed is associated with afflictions. It is also the case when we extoll our supposed good qualities or denigrate other people because we are angry with them. It is therefore, the motivation that differentiates the secondary misdeed from the major transgression.

What’s the motivation for the major transgression?

Audience: Material gain.

VTC: Only material gain?

Audience: Praise, offerings, support.

VTC: Offerings, support, honor, status, a group of followers. Attachment and arrogance are involved with that one. What’s the motivation here?

Audience: Self-centered thought.

VTC: Read the paragraph. What’s the motivation here? I just read the sentence.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: For breaking the secondary one it’s pride, vanity or anger?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Let’s go through this again.

We praise ourselves and disparage others out of pride or vanity, the misdeed is associated with afflictions.

Isn’t that the motivation for the first transgression?

Let’s go back to the first transgression:

Praising oneself and denigrating others out of attachment to material gain or to marks of respect.

That’s the motivation there. He also mentions somewhere later on about pride.

Audience: But it says here on this one we’re praising our own good qualities, the other we’re thinking material support and status, so I’m trying to discern what the difference actually is.

VTC: The difference is, on the first one we’re looking for material support, we’re looking for honor. It’s done out of attachment or arrogance. This one is the case when we extoll our supposed good qualities or denigrate other people because we are angry with them. So anger is the motivation for the secondary transgression.

Audience: A different affliction.

VTC: Yes. Different motivations.

Audience: You also said on the first one that jealousy can be also involved in your mind.

VTC: Right, jealousy. But it seems to me pride and jealousy are very close because pride is when you see yourself as higher looking down, jealousy is you see yourself lower looking up.

Audience: So that sentence is contrasting the two.

VTC: It seems to me that it’s contrasting the two, unless I’m mistaken and he’s saying it’s either pride or anger for the secondary one.

There is no misdeed in the following situation: One, this kind of behavior is useful for it favors someone’s progress or two, it inspires faith in others or strengthens the faith that they have.

Let’s see if it says in here about the motivation, if it clarifies that part about pride. Where’s the red prayerbook? Oh, I’m sorry, my mistake. It says:

Praising oneself or belittling others because of pride, anger and so on.

So, I was wrong. Oh, my praising myself just got blown away. Pride and jealousy are being separated out here. So jealousy and attachment for the first root transgression and pride and anger for this one.

33. Not Going to Attend a Dharma Teaching

Thirty-three is “Not going to attend a Dharma teaching.

The Great Way defines both the thirty-third and thirty-fourth misdeeds as the deterioration of the causes of wisdom.

We just heard the thirty-third. The thirty-fourth is “Scorning the master and relying on the letter,” which we’ll get to later.

The first is then said to be the failure to study, for it consists of neglecting to attend Dharma events. As the prime cause of wisdom is listening to teachings, staying away from them hinders the development of discernment.

When someone is teaching the Dharma formally or holding a discussion or a debate on it, if out of pride, anger or animosity we do not attend, we commit a misdeed associated with afflictions. If we do not participate because we are either too lazy or slothful to go, the misdeed is not associated with afflictions.

So pride, anger, animosity: “I know so much already, I don’t need to go to that teaching” or “This guy is a complete jerk” with a real animosity, or “This teacher insulted me” or something like that. Does this mean that every time there’s a Dharma teaching taught by any teacher you have to go? No. We’ll get into that, so don’t go to the other extreme because we have to have some reasonableness here.

On the following seven conditions, there’s no misdeed. We cannot go because we’re incapacitated by illness.

That’s quite different than if we’re lazy. If our teacher is teaching and we’re just too lazy to go, that’s not so good, is it? That doesn’t help our own practice. But if we’re incapacitated by illness and we don’t go, that’s reasonable.

The second is we’re unaware that the teaching is being given.

That’s a good reason for not going.

Third, we suspect that the person conducting the teaching might make mistakes in the explanation.

The person who is giving the teaching, they’re not our teacher, we don’t really know who they are, we don’t know their qualifications, or maybe we’ve heard something about them, or we’ve heard what kind of education they have had or haven’t had, and we have some doubts about their qualifications. Then we shouldn’t feel obliged to go if we feel that that person could be making mistakes in the explanation.

Not only have we heard this subject explained many times before, we have studied it and understood it well.

If you’ve heard the subject explained many times, studied it very thoroughly, you understand it very well, there’s no need to go. But discerning when we’ve done that, that’s an interesting thing. How do we know that we know it well? When His Holiness teaches even lamrim topics, all these geshes who themselves teach the same texts go. But would Geshe A go to hear that text if Geshe B explained it? If Geshe B was their friend and colleague, they wouldn’t go. His Holiness is their teacher, so they go. There’s some difference if you’ve really understood it and have a firm grasp on it. Still, usually even if it is your own teacher, you would go unless you’re doing service for the monastery, you’re doing some other important study, you’re doing retreat or something else is going on that’s really important.

We are generally well-trained and have already learned almost everything we need to know.

We are spending our time seriously meditating to achieve a high degree of concentration.

If you’re in retreat, you don’t necessarily have to break retreat to go listen to a teaching even if it is by your teacher. Being in a situation with a lot of other people and so on and so forth is going to be disruptive to your retreat, you don’t have to go.

For lack of intellectual faculties, we are incapable of understanding, remembering, and concentrating on what we hear.

Did you notice that one of the conditions is not “It’s hard to understand”? That’s not a condition for not going.

There is one exception in terms of necessity. There is no misdeed when we do not go to avoid annoying our spiritual master. If we suspect that our main teacher would not agree with our going, it is better to abstain. It is customary when we are already following spiritual masters to consult them before requesting instruction from another master for the first time.

If somebody is not your teacher and you’re not sure if your primary teachers would approve of you going, then it’s better not to go. Because usually, if you have a strong relationship with your primary teachers, then you would ask them first before requesting teachings or taking initiation from somebody else. If you’re just a beginning Dharma student and you don’t have a strong relationship with a teacher, then you can go to different teachings and just listen and see what makes sense to you and which teachers you want to follow, which practices you want to do and you can explore like that. But if you’ve already been doing something and have a teacher for a period of time, it’s customary to check with that teacher. Sometimes your teacher will send you to study with other teachers. Lama Zopa actually was the one who sent me to study with Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey and introduced me to several other teachers as well, so sometimes that will happen.

Audience: Why is laziness as the motivation not considered an affliction?

VTC: Why is laziness as a motivation not considered an affliction. Laziness in general laziness is an affliction, it’s one of the twenty secondary afflictions. But here what it’s calling affliction means anger, jealousy, pride, attachment, the ones that are really nasty, kind of explosive and make a mess. Whereas laziness is just, “I don’t feel like it” and sleeping too much or whatever. It still is an affliction, but here it’s called “Without affliction” because the quality of the affliction isn’t like the ones that are being called “With affliction.”

Audience: How do you discern what kind of teachings are in your area or how do you decide that kind of thing?

VTC: What do you mean, in your area? Geographically in your area?

Audience: No, I mean this particular like not going to a Dharma gathering for teaching. What you’re able to do and not able to do.

VTC: It doesn’t mean that you have to scour the area and find every Dharma teaching and go to it. I think it’s more referring that if your teacher is giving a teaching it really is for your own benefit to go; and not be angry at your teacher, “Oh, I’m so ticked off at my teacher, I’m not going to teaching,” or, “I just don’t feel like it” or “I want to go out for a hot fudge sundae instead or watch the football game.” Because with your teacher the relationship is really important. If there’s somebody there who is not your teacher you may feel like, “Oh, this is in general a highly respected lama, I would like to go and attend the teaching.” In that case if your teacher were around, you would say “Is it okay if I go?” If your teacher isn’t around then you would make up your own mind. But let’s say it’s somebody else, your Dharma friend who is giving a teaching or somebody you’ve never heard of before or somebody that you’ve heard of before but not in such good terms. Or maybe it’s even a teacher who is considered very high but you’re not sure you really want to make that karmic connection with them, then you don’t go and that’s okay.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: You’re having interpersonal problems with the other students who are there so you don’t want to go to the teaching because you’re going to have to see Sam. That’s not a good reason. You don’t skip the teaching because Sam is the person sitting in front of you—unless you’re really afraid that you’re going to lose it and start screaming and yelling and throwing your prayer book in the meditation hall. Then maybe don’t go. [laughter]

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.