Purifying non-virtue: Coveting

Part of a series of teachings given at the Winter Retreat from December 2011 to March 2012 at Sravasti Abbey.

- Definition of covetousness

- The four branches that make coveting a complete karma

- The difference between coveting and aspiration

- The karmic result of coveting

Vajrasattva 25: Purification of mind, part 2 (download)

Today we’re going to talk about coveting. This is defined as desiring possessions that belong to others and planning how to obtain them. So this is the mind of “I want.” I appreciated thinking about this as full-blown attachment, because then it makes me think, “Wow, that’s really never going to get you anything,” because it’s so exaggerated. In coveting the object can be anything that we desire. It can belong to other people, it can belong to someone in our family, or it can be something that nobody owns. We can covet any kind of thing, it’s not just material possessions. This is something I always had wondered about the meaning of coveting in Buddhism. I’m glad to have this clarified. So coveting is for not just an object—like a possession, it’s also possible to covet qualities—for example, a talent that somebody else has. That notion fit with my experience of watching my mind around those types of things. It seems to be very much a similar kind of energy.

They say it’s especially harmful if you covet something that belongs to the Triple Gem. Like, “I really want those food offerings that are on the altar.” Then, “I’m going to go get them.” You know? That’s not so good, don’t go there. That’s a little about the object of coveting.

The non-virtue of coveting

The complete intention has the three branches. First is that we recognize the object for what it is. Second is we have the intention or the wish to get it. Then third is we have some affliction, which in coveting is usually attachment. Coveting wouldn’t have to necessarily start with that affliction of attachment but it would probably end with attachment. Examples of this intention might be something like, “Oh, wouldn’t it be nice if I could have this.” Or, “I sure wish I could have that thing.” And, “It’s so nice, and would make me so happy.”

Then with the action (and remember this is all on the mental level), now the thought is developing. It often just flows from one thought to the next and goes like, “Wow, I really wish I had this. I think I’m going to get this. I’d really like to get this thing.” Now you’re moving more into action. The complete action is, “I’m definitely going to get this and this is how I’m going to do it,” because now you’ve got the plan—you’ve moved into that next phase.You can see how in those last three (the complete intention, the action, the completion of the action), they’re just a flow of thoughts, one moving into the next, strengthening.

It’s good to have an understanding about this. Because then as you see that happening in your mind you might be able to cut it. You might think, “Wow, now I’m into planning. I think I’m pretty far along here, maybe I better really slow down.”

What’s coveting and what’s positive aspiration?

This is good to differentiate. It’s good to differentiate between coveting and something that’s a positive aspiration. There are things that are useful for us in our life. And then there are things that we covet, and plan, and scheme, and connive that are things that really aren’t that useful for us in our life, because we’ve over-exaggerated their good qualities and we have that energy, really scheming and conniving and all that.

Aspiring is different from that. Here we’re recognizing the value of something—that really does have that value. We’re seeing it and our heart is moving in that direction. But it doesn’t have this kind of frenetic energy that comes along with coveting. Coveting has overestimated the value of something and then we cling, and grasp, and plan.

We could aspire to have bodhicitta in a really wholesome way, or we could actually covet it. I thought this was interesting to think about because it’s good to discern what positive aspiration is. In a sense it’s the same energy as that of desire. So then it’s nice to make this discernment. When we look at bodhicitta, we’re not overestimating the qualities of it when we’re seeing it correctly. And then our mind just has this faith and aspiring for that. It’s a light, hopeful quality of the mind versus if you were to have an incorrect understanding of bodhicitta and thinking only of how it might benefit you. If you didn’t understand it correctly you might think, “Oh, and then people would respect me and I’d be something special. I want bodhicitta.” Well, that wouldn’t be a correct understanding of bodhicitta and then you could be coveting it. I found that interesting to read.

The result similar to the cause for coveting

The result similar to the cause for coveting is interesting. The result is that we can’t complete our projects. This is because the mind is always jumping around, it’s never satisfied. You know, “I want this, I want that,” and you want so many things you never complete anything. Then we’re always involved with this energy, and it’s always dissatisfied, and we always drop that and start something else. So then we can’t fulfill our wishes and our hopes, and we’re always dissatisfied. So that’s the result similar to the cause—we can’t complete our projects.

In closing, there’s one thing I read that I have kind of a reaction to, but then I listened to something else that helped me. I thought I’d share this. When the Buddha spoke about this in one sutra, (the sutra is called The Foolish and the Wise Person), he says:

His action marks the fool, his action marks the wise person, oh monastics. Wisdom shines forth in behavior. By three things the fool can be known: by bad conduct of body, speech, and mind. By three things the wise person can be known: by good conduct of body, speech, and mind.

I always hate it when they call us fools (laughter). Then I was listening to a teaching by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. It is so funny when he said this, you know how when they talk about the 84,000 afflictions (we talked about these the other day and we boil them down to the three poisons, remember?). But there are, like, these 84,000 afflictions. He calls them, “the 84,000 fools.” Then he says you also have 84,000 constructive things in you. And those fools, they’re on a basis that won’t last, they’re based on ignorance. They can’t hold. Their foundation doesn’t hold. So, they are 84,000 fools that we have in us and they aren’t going to overtake the 84,000 good guys who have a solid basis. I find it a little easier to take when I hear about fools now.

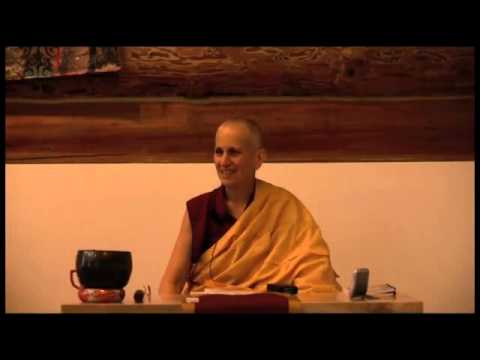

Venerable Thubten Tarpa

Venerable Thubten Tarpa is an American practicing in the Tibetan tradition since 2000 when she took formal refuge. She has lived at Sravasti Abbey under the guidance of Venerable Thubten Chodron since May of 2005. She was the first person to ordain at Sravasti Abbey, taking her sramanerika and sikasamana ordinations with Venerable Chodron as her preceptor in 2006. See pictures of her ordination. Her other main teachers are H.H. Jigdal Dagchen Sakya and H.E. Dagmo Kusho. She has had the good fortune to receive teachings from some of Venerable Chodron's teachers as well. Before moving to Sravasti Abbey, Venerable Tarpa (then Jan Howell) worked as a Physical Therapist/Athletic Trainer for 30 years in colleges, hospital clinics, and private practice settings. In this career she had the opportunity to help patients and teach students and colleagues, which was very rewarding. She has B.S. degrees from Michigan State and University of Washington and an M.S. degree from the University of Oregon. She coordinates the Abbey's building projects. On December 20, 2008 Ven. Tarpa traveled to Hsi Lai Temple in Hacienda Heights California receiving bhikhshuni ordination. The temple is affiliated with Taiwan's Fo Guang Shan Buddhist order.