Bodhisattva ethical restraints: Introduction and vows 1-3

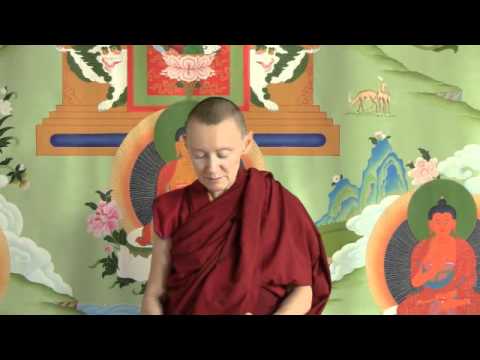

Part of a series of talks on the bodhisattva ethical restraints. The talks from January 3 through March 1, 2012, are concurrent with the 2011-2012 Vajrasattva Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey.

- Introduction

- Explanation of vows according to a commentary by Dagpo Rinpoche which uses Tsongkhapa’s explanation

- Vows of engaging bodhicitta

- Vows 1-3 are to avoid:

- 1. (a) Praising yourself or (b) belittling others because of attachment to receiving material offerings, praise, and respect.

- 2. (a) Not giving material aid or (b) not teaching the Dharma to those who are suffering and without a protector, because of miserliness.

- 3. (a) Not listening although another declares his/her offense or (b) with anger blaming him/her and retaliating

When a precept has more than one aspect, doing just one aspect constitutes a transgression of the precept.

Bodhisattva ethical restraints 02: Introduction and vows 1-3 (download)

Mindfulness doesn’t mean to just bear attention on what you’re doing. We keep mindfulness on our bodhicitta motivation. We anchor our mind to that motivation. That motivation is always, if not manifest in our mind, then latent and easy to manifest in our mind. In that way, we maintain mindfulness on bodhicitta. When we have bodhicitta, there are certain actions we want to do and certain actions we don’t want to do. Certain actions are conducive to the benefit of all sentient beings, and certain actions are the opposite.

The bodhisattva vows, the different precepts in the bodhisattva ethical code, are like advice that says, “Okay, when you really have the aim to become a Buddha for the benefit of sentient beings, do these things, and try to avoid these things.” It’s like an accumulated book of good advice and tips on how to accomplish your aim. Like I keep saying, don’t see precepts and samaya commitments and things like that as tying you down, but as things that are showing you how to accomplish what you want to accomplish. It’s really important to really keep that in mind.

We think, “Oh yes, sentient beings want happiness like me. They want to be free of suffering just like me. How am I going to accomplish that?” Well, I’ve got to become a buddha because then I won’t have all the impediments I have right now. I’ll have the skills that I don’t have right now. So: “What do I need to do to become a Buddha? Tell me how to do it.” That’s what the teachings are all about. The bodhisattva ethical code is the real practical advice about paying specific attention to these kinds of actions and the motivations that lie behind them. Because if you get involved with them, you’re going to go opposite to the direction that you want to go to.

It’s like how in magazines, they have “18 tips for a better life.” So, we now have “18 tips to become a buddha.” We have eighteen major tips and 46 minor tips. That makes a good magazine article—the kind with bright red letters on the head and some sexy person on the front. Then everybody might follow the bodhisattva path; wouldn’t that be nice? But it’s minus the sexy person on the front. We’re going to really be exploring what these tips are that will lead us in the direction that we want to go.

I want to explain a little bit about the three different ethical codes in the Nalanda tradition. Because we have the pratimoksha or individual liberation ethical codes, the bodhisattva ethical code, and the tantric ethical code. Sometimes these are called the three sets of vows, but they aren’t really vows. They’re really more like ethical codes or sets of ethical restraints.

The pratimoksha or individual liberation ethical codes

In the pratimoksha or individual liberation vows, that’s where we have the five lay precepts, your eight anagārikā precepts, the novice monks’ and nuns’ precepts, the shiksamana precepts and so on. Those are all part of the individual liberation ethical code. All of those precepts you take from somebody—you take from a preceptor, or you take from the Sangha. You take those in the presence of somebody, and those different sets of pratimoksha precepts or individual liberation precepts came about, we could say, by necessity or by trial and error.

In other words, when the Buddha was alive—actually for the first twelve years—the Sangha didn’t have any precepts because nobody did anything that was terribly obnoxious. Then when people started doing things that were kind of offensive or unethical, based on real-life events, the Buddha made different precepts that say, “avoid this” and things like that. That’s how we got the five precepts; that’s how we got the monks’ and nuns’ precepts, and so on. It was because specific individuals did naughty things. So, there are the group of six monks and the group of six nuns, and they say that due to the kindness of these twelve naughty individuals we have the precepts we have. [Laughter]

There is one nun in particular, Sthulananda—oh, I can’t believe this person. In some ways, she might very well be a caricature, but she might also be a real person. Boy was she getting into stuff! And there was the same thing with the monks, who were always doing one thing or another. This is how those precepts evolved.

The Buddha would establish them when news of a certain naughty action came to his ears. Sometimes he would say something, and then a different situation would come up, and he would have to adjust it more or less for that different situation. It was like, “Don’t do this except in these circumstances; then you can do it.” Each of our monastic precepts has a story behind it, and then stories that made the exceptions and so on.

Three levels of practice

That’s the first level of precepts. To take those, you take refuge in the Three Jewels. Then at that time you also have the opportunity to take the five lay precepts. That really sets the ground for your practice. Sometimes I’ve described the practice in terms of three levels of “stop being a jerk,” because a buddha is not a jerk. So, there are three levels of practice to stop being a jerk. The first one is, “Let’s get our everyday ethical material together so that we stop being like a super-big jerk by killing and stealing, using our sexuality unwisely/unkindly, lying, and taking intoxicants.” That is the bare bones. Then, as manifestations of that, are all of the hundreds of other precepts that the monastics have.

That’s the first thing we do to really stop being a jerk, and you can see it. Look at the people that you’ve known in your life. Who are the people that bug you the most? [Laughter] Yes, it’s the jerks! What do the jerks do? They kill, they take what hasn’t been given to them, they sleep around and flirt and do all sorts of unbecoming things. Then they lie about everything they do, speak harshly to others, get loaded, and their behavior is completely uncontrolled. When we think of ourselves, that’s hard, but think of the people you least want to be friends with. They’re the people who do these five things. And every religion agrees, except for Catholics who make an exception for alcohol—I’m joking. But they do! They do, and the monastics are allowed to drink in that tradition. I find it amazing. Okay, I better be quiet now. But you can see in Islam, you’re not supposed to drink, for the same reason. People just get crazy when they do. So, that’s the first level.

The bodhisattva ethical codes

Then the second level is the bodhisattva level. With the first level, we’re trying to control our own behavior and not create the cause for a bad rebirth. With the second level, we’re really trying to work for the benefit of others. First you generate the aspiring bodhicitta, which is when you aspire to become a buddha for the benefit of all beings, but you’re not committing to do it yet. You have that aspiration.

Then, when you’ve progressed a little bit more and you say, “I really want to engage in the bodhisattva path and really practice it,” then you have what’s called engaging bodhicitta. And then you take the bodhisattva ethical restraints. Aspiring bodhicitta is like wanting to go to Dharmsala, and engaging is like getting your ticket and your visa and getting yourself to the airport and on the plane. You can see the difference in commitment there, so there are differences in your practice as well. That’s in terms of the bodhisattva ethical conduct.

Then, on the basis of your individual liberation and your bodhisattva practice, you enter the Vajrayana. At that time, when you take initiation into the upper two tantric classes of yoga and highest yoga tantra, you take the tantric ethical code and also the samaya—the commitments, the pledges.

When we look, there are increasing scales of difficulty. With the pratimoksha ones, you start with the five lay precepts and the monastic precepts, and that already can be difficult. Then the bodhisattva precepts are more difficult. Then, the tantric precepts are even more difficult to keep, because each set is making our mind more and more refined, making us more and more aware of our behavior. So, that explains the increase of difficulty.

Also, with our individual liberation precepts, to break those you have to either do something or say something. Of course, your mind is involved, and the mind is going to determine a lot of the action and how heavy it is and if you actually completed it and so on, but you actually have to do something or say something for the pratimoksha precepts. Those are precepts that really govern actions of our body and speech. They relate to the mind, but you can’t break them just by the thoughts you have in your mind. You cannot commit a full transgression just by the thoughts. Because the mind is the root of everything. First the mind goes, then the speech, then the body. In practicing restraint, we start with the grossest and the easiest concern, which is our body and then our speech. And then the most difficult to restrain is our mind. We can see that. Before you say something, something is going on in your mind. And before you punch somebody or pat them, something else is going on in your mind. So, the mind is the source of the verbal and physical actions that are restrained by the individual liberation precepts.

Some of the bodhisattva precepts regard what we do; some of them also regard what we say; and some of them you can break just by thinking—by your thought alone. It’s much more refined because it’s really getting us to look more closely at what our thoughts are, what our motivations are, what kind of mental factors are manifest in our mind at the time, what kind of emotions we have that are motivating us to do something. They’re more refined and they’re more difficult to keep.

The tantric ethical codes

Then the tantric precepts and commitments are even more difficult because those have a lot more to do with the mind. Some have to do with body and speech, but a lot have to do with our mind. They’re much easier to break. Also, they are more complex because the kind of mental actions that we’re becoming aware of with the tantric precepts are much more subtle than with the bodhisattva precepts, which are much more subtle than the individual liberation or pratimoksha precepts.

Similarities but also some differences

Before you take these three sets of vows, you’re not really supposed to know them. Nowadays, people often read something, but technically speaking, you’re not supposed to fully know them before you take them. The bodhisattva precepts are different, and there is an exception. With those, we’re really encouraged to learn, and to learn about them even before we take them, and to even practice as if we had them in order to help us reaffirm or to cultivate that bodhicitta motivation. That’s why teachings on the vinaya precepts or the tantric precepts are only open to the people who have them, but teachings on the bodhisattva precepts are open to everybody.

With the individual liberation precepts, if you transgress a root precept—with all the factors complete—then you’ve lost that ordination, and there is no way to retake it. For example, monks and nuns have different amounts of root precepts, and if we break any of those, with all the different branches complete, then we’re no longer monastics, and we can never re-ordain in this life. With the other categories of precepts that are not the root ones, if we break those, we confess and restore them on the posada days, like when we did the confession and restoration here. Or if we’ve done some of the major ones but not fully, then those we restore in the presence of the Sangha, making confession and purification. Sometimes the Sangha gives you something to do to give you space to think about what you’ve done and decide if you really want to humble yourself and come back and be a part of the community again. But if you break those completely then it’s finished.

With the bodhisattva precepts, if we break the root ones completely, we lose the ordination, but it is possible to retake it. And it’s the same with the tantric precepts and so on. There are different methods to retake them. With the bodhisattva ethical code, we can retake it in front of a teacher, or we can also do it on our own. So actually, once you’ve taken the bodhisattva precepts, we’re supposed to take them on our own every morning and every evening. For those of you who are doing the six-session yoga, you can see that there is a verse particularly for that so that you fulfill that commitment when you do your six-session. In that way, you are renewing your bodhicitta ethical code or ethical restraints on a daily basis and strengthening them by retaking them every morning and every evening.

For the tantric precepts, although we have a prayer, kind of, in which we imagine retaking them and go through the precepts and through the commitments—the samaya for the five dhyani buddhas—we’re not really retaking it when we just do that as part of our daily practice. It’s certainly imprinting it more in our mind, but we’re not really retaking them and purifying. To really do it with the tantric precepts, if you do 100,000 Vajrasattva then you can purify transgressions to the tantric precepts. Or, once you’ve done the retreat on that deity with a certain number of mantra and the fire puja that concludes the retreat, then you can do the self-initiation, and you can retake the tantric ethical restraints at that time. Or you can retake the initiation with a master, and at that time you also retake all your tantric precepts and commitments.

With each of these levels of precepts, there are some similarities but also some differences according to taking them and how they came about and what constitutes a break and so on and so forth. We’ll be getting into that.

Bodhisattva precepts origin story

While the monastic precepts of individual liberation were created due to the “kindnesses of these naughty monastics,” the bodhisattva precepts weren’t organized as an ethical code from the very beginning. Rather, different bodhisattva advice was sprinkled throughout the Mahayana sutras, and then it was brought together, and so, let me make sure I explain this correctly.

Arya Asanga was one of the great bodhisattva scholar practitioners; he lived in the fourth century, I believe. Then he accumulated a lot of the advice from different Mahayana sutras into his ethics chapter of a text called The Bodhisattva Grounds, or Bodhisattvabhūmi. He also wrote another text called the Srāvakabhūmi, The Hearer’s Grounds, and he gives a lot of information about meditation in there and a lot of the practices common to all Buddhist practitioners. But in The Bodhisattva Grounds he’s really focusing on people who want to practice the bodhisattva vehicle. In the ethics chapter, he detailed four major transgressions and then 46 minor ones, or auxiliary ones.

Chandragomin, who was a lay person but a bodhisattva, who was also at Nalanda University, I believe, condensed Asanga’s elaborate explanation into a short text called the Twenty Verses on the Bodhisattva Ethical Restraints. He condensed the four major and the 46 auxiliary ones.

Asanga had asked those reading his text to also go through the rest of the Mahayana scriptures and see what other kind of advice the Buddha put in them about what to practice and what to avoid as a bodhisattva. And so Shantideva, the author of Engaging in the Bodhisattva’s Deeds, did just that, and he wrote a text called the Shikshasamucchaya, or Compendium of Trainings. Here he compiled a list of fourteen major transgressions that were based on the Ākāśagarbhasūtra. Now, one of the fourteen transgressions from Shantideva’s list was the same as one of the root ones in Asanga’s list, so that brings us to seventeen root precepts. So, where did the eighteenth one come from? Shantideva got it from another sutra called the Sutra for Skillful Methods. So, the eighteenth bodhisattva root precept came from the Sutra for Skillful Methods. That’s how we got this ready-made list of 18 plus 46. It’s not like the Buddha said, “Okay, here they are,” and went, “One, two, three four, five. . .” But rather, they were collated over time to make the list that we have now.

What I wanted to do is go through these, and I was going to do it by reading from Dugpa Rinpoche’s commentary, because he referred to Asanga and Chandragomin and Shantideva and so on and gave a commentary on each of these. I thought to read it, and we can just kind of discuss it as we go through it. Then after each time, go back and in your meditation think of some examples in your life that apply to the different precepts as we go through them.

1. Out of attachment to gain and honors, praising yourself and belittling others.

Chandragomin says:

Out of attachment to gain and honors, praising yourself and belittling others.

Dugpa Rinpoche says the first major transgression of the bodhisattva vows consists of praising oneself and denigrating others out of attachment to material gain or to marks of respect. So, you can see here that it’s for a specific purpose. It’s like, “I want something out of somebody. I want them to think I’m wonderful; I want them to bow down to me or be my little groupies that follow me around or praise me to other people. And I’m kind of jealous of this other teacher who has a good reputation, and I don’t want people to follow them, so I disparage them and show how I’m a much better practitioner and my teachings are much better. ” That’s called having a big ego. But there are so many subtle ways to do this in which you don’t look like you have a big ego. We’re very skillful in this kind of thing: how to appear humble but at the same time promote ourselves in a selfish way. We know how to do it.

In The Great Way, which was Lama Tsongkhapa’s commentary on the bodhisattva ethical code, he says:

From three angles, the object, the words spoken, and the motivation, the meaning becomes clear.

In looking at this precept, we’re going to look at the object who is the person spoken to, the contents of the words that were said, and the motivation behind the words.

The first aspect, the object, is always a person other than ourselves. In other words, if we talk to ourselves we might commit a misdeed, but never a major transgression.

This happens when we sit here and go, “Oh, I’m so much better than that other person. I want everybody to follow me and not them.” If you’re sitting there and talking to yourself instead of saying Vajrasattva then your lips are moving, but that’s not what you’re saying. That’s a misdeed. We’re not saying it’s karma-free. It’s a misdeed, but it’s not a major transgression.

Furthermore, the person we address must be capable of hearing and understanding what we say. He must therefore be of the same kind—or, in other words, a fellow human being. Speaking to either an animal or a being belonging to another realm of life does not qualify.

So, the transgression is not complete by talking to ourselves alone in a room or talking to a dog or a cat. And then the second aspect was the content of the words that are spoken. We may proclaim good qualities that we do not have or at least that we don’t have to the extent that we do, or we disparage others and deny the good qualities that they actually possess.

The transgression therefore involves misrepresenting the truth either through an outright lie or by simple exaggeration. It is also necessary that the object of our scorn has excellent qualities and be generally respected for them. It is someone held in esteem and trusted by others.

Here he’s really getting into the details: it needs to be somebody of high esteem, you need to have a certain motivation, and it’s a distortion of the truth. Even though these are technical points that make it actually much more difficult to break, it’s still good to think of the times when we put ourselves up and put others down and it’s not necessarily through lying or exaggerating. It’s really telling the truth but telling the truth in a very special way with a very special motivation, like “that person doesn’t know what they’re talking about.”

This precept is particularly given in a Dharma context, because it’s very easy if you get into a position of being a leader in a Dharma center or leading meditations or discussion groups or giving Dharma talks. You want to hold onto your students because they’re the ones that give you their respect, and they’re the ones who give you offerings. You don’t want them going to somebody else! Because then your livelihood is at stake. So, this is the kind of thing that a Dharma practitioner could very easily do.

Now, although it may be focused particularly on that, surely in so many other aspects of our life we can do it, too. Even if you’re working at a job, there are ways of putting yourself up and putting the other person down—either by lying or exaggerating, or sometimes not by lying and exaggerating. But it’s with this very conniving motivation because we want to get something out of it: “I want my boss to give me this new opportunity, or the promotion. I want the raise. I want to be able to travel. I want to be captain of the team, or whatever it is.” So, it can apply to other things as well. It sounds really awful when applied to Dharma situations. That’s why we need these kinds of precepts to protect us. Just because we’re Dharma practitioners doesn’t mean that all the rubbish is gone from our mind, as you see by one day in retreat. [laughter] It becomes abundantly clear, doesn’t it?

The third aspect, the motivation, is attachment to either material goods or honors. It is not necessary to crave both, however; one is enough. In the first case, the goods we desire must belong to someone other than ourselves. They must not be communal property—for example, a house owned collectively with other members of our family. This principle does not apply to attachment to honors, because clearly honors are not owned in the same way. Therefore, if we praise ourselves or belittle someone else out of longing for signs of respect, from our parents for example, we commit a major transgression.

Now, think of that as it relates to your brothers and sisters. Do you sometimes praise yourself and put them down because you’re wanting praise and approval from your parents? Or, maybe you do it because you want to be on your parents’ good side, and maybe they’ll give you a little bit more money in their will or whatever? Actually, forget the will; who waits that long? Maybe they’ll give you some cash right now. When you live in your parents’ house until you’re forty nowadays, why not? [laughter] So, I think that’s an interesting example there: putting ourselves up and putting somebody else down to gain our parents’ respect or praise or to get something out of them. And it’s the same way with our employer. It’s the same way with somebody if you’re trying to attract them to yourself but they’re dating somebody else: I put myself up and put them down. Because you want that person to like you and respect you and stuff like that.

However, it is legitimate to praise ourselves with the idea of acquiring material goods when we intend to use them for a good purpose, such as making offerings to the Three Jewels or helping the needy. Since it is not done for the sake of personal profit prompted by attachment, there is no transgression. Here, if you speak about your good qualities, you’re not going to be exaggerating them or making up ones that you don’t have. This would be more like when somebody needs some money for doing a Dharma retreat or making offerings—actually a Dharma retreat could be more for yourself—but you want to make offerings or you want to maybe go somewhere to help at a certain temple or center or something and need support for that. Then to say what you’ve been doing so that you’re worthy of that support, that’s completely okay. Because you’re not exaggerating, and it’s not so much your support; you need the money because you want to make offerings, or you want to help, or something like that. That’s okay.

For example, we’ve gotten involved with the Youth Emergency Services in Newport, trying to help the homeless teens in our area. If we speak about the good things that the Abbey is doing for people in the attempt to raise some money for the Youth Emergency Services, then that wouldn’t fit into it because it’s not for our own personal gain. Or, if we talk about the good qualities and things that the Abbey is doing because we’re trying to build Chenrezig Hall, and we’re not exaggerating or making up things, then that’s also okay because that is not for personal gain. That’s actually for the benefit of most of the guests. If it was just the people at the Abbey, we don’t need to build that big building. That’s mostly for the guests, so to really let people know, that’s completely okay. But what we want to avoid here is just this very egotistical thing way of thinking: “I’m so great, don’t trust them, the quality of their teachings is lousy and they’re this, and this, and this, and this, and it’s made up, and it’s done out of this very corrupted motivation.”

That’s also going to be different than warning somebody of a teacher who is doing controversial things. If somebody says, “I’m thinking of going to teachings by so-and-so,” and you know that there has been so much stuff on the internet about so-and-so and their behavior, then you might say, “Just be aware that that person is quite controversial, and you might want to really investigate very carefully before you get involved.” That’s okay to say because that’s done out of care and concern for the other. It’s not out of attachment to yourself to get that person to follow you or to give you something, or things like that.

It’s very good to think of different examples here and really know what the details are, because otherwise we might get very confused and think that we shouldn’t at all speak of our own good qualities, even in situations where people ask us to tell them the good things that we’re doing. They like to feel inspired and want to know, and then we think, “Oh, I’m going to break a precept by doing that.” That’s why we need to know the precepts well so that we don’t hold back unnecessarily and so that we don’t speak out of a really rotten motivation to others and to our own detriment.

The motivation has yet another aspect. Our words must stem not only from attachment but from jealousy as well. There is no reference to jealousy in either the ethics chapter from Asanga or in The Twenty Verses on the Bodhisattva Vows (by Chandragomin).

However, Shantideva in his Compendium of Trainings names jealousy as a further requirement for the motivation referring directly to the Ākāśagarbhasūtra for this information.

Therefore, to commit the first transgression, not only must we be attached to goods or to signs of respect, but we must also be jealous of people’s excellence such as their nice belongings or other’s consideration for them. Because we cannot bear the thought that they enjoy these, we exaggerate our own good qualities and denigrate the people in question who are respected by others. This is done either in the hope of gaining some material benefits – gifts, cash, food, clothes, means of transportation, and so on – or because we yearn for signs of other’s respect for us – good seats, distinctions, tributes.

This refers to people doing all sorts of things for us so that we can just stride in and feel very important.

Furthermore, the people we speak to must be capable of hearing and understanding what we say. In fact, we can speak scornfully directly to the worthy person we disdain or to someone else who respects that person.

So, you can speak right to the person themselves or to somebody else.

When all these conditions are fulfilled and the four binding factors are present as well, the first major transgression is effectively complete.

We’ll get into the four binding factors a little bit later. But they’re listed in the book there, you can read them.

2. To those in distress who lack a protector, out of miserliness, not giving wealth or Dharma.

Chandragomin says:

To those in distress who lack a protector, out of miserliness, not giving wealth or Dharma. The second transgression of the bodhisattva vow is made by refusing to share the wealth or the knowledge of the Dharma that we possess. To better understand the meaning of this transgression, we will investigate its following objects: First, the object or the petitioner;

This refers to the person who is asking.

Second, the substance request; third, the subject who receives the request;

So, this would be us.

Fourth, the motivation. The object is a petitioner with particular traits who is seeking wealth or spiritual instruction. As Acharya Chandragomin specifies in his Twenty Verses on the Bodhisattva Vow, it is ‘those in distress who lack a protector.’

This is somebody who is really in distress who doesn’t have somebody else to turn to—that’s the person who is asking us for either material goods or for Dharma instruction.

Thus, the petitioners must be truly in need. They may be hungry and have nothing to eat, have no clothes to wear, or no roof over their head. Furthermore, they must have no other recourse but us. They must not have any family or friends or someone to guide them that they feel they can trust. In other words, when people are in need materially or spiritually, but have the possibility of appealing to someone else for assistance, there is no fault in refusing their request.

The same two conditions apply to spiritual instruction: the people must have no one else to whom they can turn for the teachings that they are specifically seeking; they must be completely dependent on us for them and place all their hopes in us.

And the final point regarding the petitioner is the way that they make their appeal. It must be done sincerely and properly, which is to say according to religious and social conventions.

So, if somebody comes up and just says, “Hey, give me this,” that’s not a proper request. Or, if you know that the people have somebody else that they can also rely on, then if you refuse, it’s okay. Of course, if they’ve already checked with all those other people and at this point they really don’t have anybody else to rely on, then it’s another situation.

The second aspect requested:

The substance may be one of two kinds: material goods – money, food, clothes and so on – or spiritual instruction. An exception is made regarding a request for dangerous substances, such as weapons, poisons, or anything else that the person could use to physically harm himself or others. There is no fault in refusing these or for that matter any spiritual instruction that potentially through misuse could damage the petitioner or other people. This can be quite complicated in the present context of social or medical assistance. For example, when a drug addict appeals to us for illegal substances or for funds to purchase them, we may wonder should we or shouldn’t we provide them with this?

Some may think that being a bodhisattva means to give everybody whatever they ask for because we’re supposed to be generous. Somebody asks, and maybe they really need, so we should give them the money to go buy their drugs or alcohol or go get it for them. Somebody could be thinking like that.

In bodhisattva practice the answer is found in terms of two criteria—temporary and long-term benefits. Providing addicts with drugs in most cases will provide a short-term benefit: the user will momentarily be satisfied. In the long-term however, drugs are harmful, and for that reason we will not supply users with them.

This is very clear. Sometimes this can happen with a family member who is drinking or drugging. It can happen when you stop at a gas station, and somebody comes up and asks you for something. I remember in Washington D. C. when going for the Kālacakra, I was walking to the stadium one day and somebody asked me for something. I like to give food, so I handed him food, and he didn’t want that. So, then I said, “Well, I’m sorry, I can’t help you. I’m a nun.” I didn’t want to give somebody something that could be used for something else. Of course, they could be using it for transportation or a place to stay, I don’t know, but in that kind of situation I didn’t want to take the chance. And I figured food is always something nutritious.

The long-term effects override the temporary benefit. Conversely, if something carries a temporary drawback but an ultimate advantage, it should be furnished.

We’re always thinking here in terms of our generosity. And basically, in terms of any choices we make in our life: what’s the short-term benefit and what’s the long-term benefit? If something is of neither benefit in the long-term or the short-term, don’t do it. If it benefits in the long-term and the short-term, do it. If it’s not beneficial in the short-term, but it is beneficial in the long-term, do it. But if it is beneficial in the short-term and not in the long-term, don’t do it. This is very helpful criteria for when we have decisions to make in our life. Really look long-term. And especially when we’re looking long-term, consider not just the criteria for what material or reputation gain will I get in the long-term, but what about my ethical conduct in the long-term? What about my bodhicitta practice in the long-term? Which situation is going to be most conducive for my developing in the way that I want to develop in the long-term?

An adequate subject is a person who has the possibility of giving the substance that is sought, because he has them or has the possibility of procuring them.

So, we’re the subjects and somebody’s asking us for something.

To commit a transgression, we must have received a request for a form of wealth or a teaching that we have in our possession and yet refuse to give. It is easy to understand that if we do not have what is asked of us, there is no fault in refusing it. The motivation behind the refusal is miserliness.

So here, too, we’re looking at a specific motivation. It’s miserliness.

We incur the second transgression when out of stinginess we decide not to share the harmless belongings or Dharma teachings that were requested of us. In addition, for the fault to occur, it is not necessary that the petitioner be aware of our refusal.

So, we don’t have to say “no” directly to their face. We can wiggle out of it.

We might wonder whether we contravene this precept when we do not give money to charities that solicit our financial support for projects in the Third World, for example.

Before I tell you about his thought on this, what do you think? Do you think that fulfills the criteria given so far?

Audience: No.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Why not?

Audience: Because he has other places to go.

(VTC): Yes, there are other places to go.

It seems unlikely that refusing donations to charities constitutes transgression of the bodhisattva precepts, but to check we must consider each aspect of the transgression. The first requisite is that the person be truly in need. The second is that he has no one else to turn to for assistance. This suggests a personal contact and a personal approach. The procedure in fundraising for charities is far from personal, and the soliciting charity itself is not in need. Moreover, fundraising campaigns are often organized to help large groups of people, even entire nations, as in the case of famine-ridden regions in Africa for example. Individually we are not capable of resolving such widespread problems. We do not have the faculties or the means to fulfill all their needs.

If a large number of people were to combine their efforts they might successfully alleviate a degree of suffering temporarily; however, we know that the solution would be short-lived as long as the cause of the problem is not treated. It is sometimes better to contribute towards projects that offer solutions to problems to prevent similar situations from reoccurring in the future.

I think that’s really something to think about. It’s the whole thing of “the house is on fire,” and putting out the fire versus preventing the house from catching on fire. In different situations you definitely need to put out the fire, but other situations it’s better that we keep it from catching on fire to start with.

For all these reasons, the decision not to give money to a charity does not imply a transgression of the bodhisattva precepts.

Now, what about when you get something and then somebody asks you for that something. You know they have somebody else that they can ask, but you also feel like, “Geez, why are they asking me? Ask somebody else. This is something that I have, and I really want to hang onto it.” Then what?

Audience: Miserliness is up.

(VTC): Miserliness is up, right. Have you completed a full transgression?

Audience: No.

(VTC): No, but have you completed part of a transgression?

Audience: Yes.

(VTC): Yes, there is some kind of clinging on our part. So, even though we may not commit a full transgression, it’s very good for us to notice the different ways that clinging and miserliness arise in our mind.

You might wonder, “Well, how can somebody be stingy about the Dharma?” Well, as far as I’ve heard it described, some people don’t want to give somebody else a teaching because then that person will be capable of teaching it themselves, and then they will be competition. It’s the same way that sometimes you don’t want to give someone some material goods because then they’ll have it and you won’t, or they’ll get the respect for having it and you won’t. I guess it could be the same in terms of teachings. Not wanting to help somebody, that’s a pretty rotten motivation, isn’t it? Now, what about if somebody asks for a teaching that’s way above their head? In that case, it may be better to say no.

Audience: [Inaudible].

(VTC): It’s better to say no. I remember one time when Rinpoche was in Dharamsala, and I went to see him, and I asked him some question about emptiness. He looked at me and said, “You wouldn’t understand the answer even if I explained it to you.” And then he proceeded for maybe 15-20 minutes to talk about emptiness. So, I don’t know what happened.

3. Not listening to others although they apologize, and out of anger, striking others.

Chandragomin says:

Not listening to others although they apologize, and out of anger, striking others. The third major transgression of the bodhisattva precepts is double. It first consists of not forgiving the people who have wronged us, of yielding to our anger towards them, of refusing their apology and verbally abusing them. Once we are overcome with wrath, its second aspect involves physically abusing the people concerned.

This is really unbecoming for a bodhisattva, isn’t it?

This transgression therefore takes two forms: refusal of an apology and physical mistreatment. Both have the same underlying cause: giving into and maintaining angry feelings within us, which is where the fault actually lies. In the first case, overwhelmed with anger we are led to refuse their apology and to assault them verbally by covering them with insults for example. When that is not enough to relieve our anger, we attack them physically, strike them, beat them, or tie them up or have them incarcerated.

Before we go on here, have any of you received an apology and not forgiven the person? Have you ever had a person come to you and sincerely say, “I’m sorry,” and you say, “Well, I’m not going to forgive you; I don’t accept that apology,” no matter how sincere they are? Some people say yes, some people say no.

Audience: [Inaudible].

(VTC): Well, that could be part of it. They might be sincere—they look sincere—but we’re so angry that we can’t see the sincerity, so that’s included here. They might be very, very sincere, but we’re so angry that no matter what they say or do, we completely refuse to accept their apology. It can happen, can’t it? And then we’re holding onto a grudge tremendously. It’s like, “I want to get back at them for what they did to me.” They come and apologize. We could be so mad that we’re holding a grudge, we want to retaliate, and we want them to admit their fault. So, even if they come and admit their fault, we want to rub it in: “Oh, so you finally understand how much you hurt me? You didn’t realize it at the time? You just took your liberty in this and this and this and this. Your apology is total b. s. Why did you do it in the first place? I’m never going to forgive you.” When you watch TV and movies, this is the context of things, so it has some relationship to real life.

In both cases, the object of our wrath must be a fellow human being, someone who is capable of understanding what we say. For the first aspect of the transgression, refusing an apology, the objects are people who have harmed us in some way and have later come to regret their deed and earnestly wish to express their contrition in the form of an apology. Their sincerity is important. We often say “sorry” automatically, without really thinking of what we are saying. Frequently it is a mere reflex. In the present context, the apology must come straight from the heart and be motivated by a genuine wish to make amends for a wrong.

And people do apologize like that. They come to realize that they did something that was unbecoming or damaging, and they regret it.

In addition, it must be presented at the right time and in the right way. People who wish to excuse themselves must not do it in an ill-considered and careless fashion; they should take into account the time and place and present their apology with a respectful attitude in accordance with tradition and social customs.

So, it’s not just “Ah, and by the way, I’m sorry I stole your wife.” It’s a very sincere thing and not just something you say to somebody when you’re walking by or when there are a bunch of other people around so that they can’t really consider what you’re doing.

Choosing the right time for our activities is invariably important.

This I find quite interesting.

In the secondary precepts the choice of the appropriate place and occasion is frequently stressed. It is perfectly logical. For example, if people are very annoyed with us and still under the sway of anger, there is no point in trying to seek their forgiveness for they will not listen.

That’s true, isn’t it? If somebody’s still really mad then there’s no point in apologizing yet.

Offering our apologies in fact will most likely have the opposite effect to the one we are seeking. Far from pardoning us, they will probably become even more furious than before. It is also unfitting to try and excuse ourselves when a person is very busy or engrossed in some other activity. We need to choose a moment when the person has the time to listen to us and would be willing to do so. We can see that the instructions for bodhisattva practice are very pragmatic and concern situations we encounter daily. Using them can greatly improve the quality of our lives and help those around us. By following these guidelines, we will be better equipped to deal with a large variety of circumstances. We will relate to others in a way that will create greater harmony and ultimately benefit society at large.

Here, he’s talking about not only place and timing regarding when we apologize, but also when we do anything. Because lots of times the person is involved in doing something else. They’re involved in thinking something else. They’re involved in going somewhere, and we just grab them and say whatever we need to say, without any concern for what their situation is. We do that lots of times in our life, and it leads to a lot of feelings of tension between people. It’s not actually something unethical—we’re not lying or stealing or whatever—but we’re being very inconsiderate because we want to say something. We want the answer. We want to get it off our chest, or whatever it is, and it doesn’t matter to us what’s going on with the other person.

He’s saying in all the situations in our life to really think: “When is the right time to say this? Where is the right place to say it? How is the right way to say it?” Do this Instead of just “blaaaah.” This happens at the Abbey a lot, actually when people are in the middle of doing something. We won’t go into it, but it happens a lot and can be very disturbing. So really, when being considerate of others is at the forefront of our mind, then we really think right time, right place, right method. It always turns out better if we do.

Remember when you were a teenager, and you wanted to ask for your parents’ permission for something? We always were very considerate of the right time, the right place, the right words. We didn’t rush it or hurry it; we waited for the right thing. We buttered our parents up, and then asked for what we wanted. It’s true, isn’t it? But then when there are other situations, when we just want something quickly, then we just do it any old way, and it’s likely to create not very good energy with the other person. When we’re considerate, it creates a much better energy. We got our parents to do things for us because we knew how to ask in the right way. But I’m not saying we should make it a practice of buttering people up.

The first aspect of the transgression, therefore, involves continuing to harbor bad feelings and resentment and refusing to accept apologies that are offered properly at a suitable time. There may be several steps to the process of rejection. First of all, we decide not to accept them. Then we make our decision known; for example: “I cannot pardon you for what you have done.” Then maybe we’re angry, like, “Are you out of your beep-beep-beep mind? I am never going to forget this!” Or maybe we say, “What you did is unforgivable and will not be easy to make up for.” We’re not going to be very sweet. We’re going to use a lot of swear words and really let it be known that they had absolutely no business doing what they did. They’re so selfish, the scum of the earth, and what they did is totally inexcusable. Any idiot knows that. So, why are they even asking us for an apology? We really rub it in and humiliate the person tremendously. Have you ever apologized to somebody and had them not accept your apology?

Audience: Yes.

(VTC): What was that like?

Audience: [Inaudible].

(VTC): It’s very painful. So then when we flip it, when we don’t accept somebody else’s apology, it’s the same kind of thing.

All the while we continue to relentlessly bear a grudge against the person who is asking for forgiveness. If we continue to feed our anger instead of letting it go, we may very well be led to commit the second aspect of the transgression, which is physical abuse of various sorts.

That’s when it’s like, “Are you crazy?”

The motivation of the transgression is resentment, the fact of holding a grudge. Someone may make us very angry by speaking to us in a way that we find offensive for example, and instead of forgetting the incident we brood over it. Keeping it foremost in our mind, we prolong our feelings of anger.

Are any of you doing that in your meditation during retreat—going through things that have happened in the past? “Oh, how dare they do that!” Are you having a nice, focused concentration on that with no distraction? Vajrasattva doesn’t intrude at all. Lunch doesn’t intrude at all. Nothing intrudes. You’re 100% focused on “Oh, they did this to me; I was so hurt.” Who says we can’t concentrate?

Questions & Answers

Audience: They say the vows must be taken every morning. If not, is it like losing them?

(VTC): Yes. If you’ve taken the bodhisattva precepts before, yes. You should take them every morning and every evening.

Audience: How do I take them?

(VTC): You can use any of the prayers to do so—even the prayer that we do at the beginning: “I take refuge until I am enlightened. By the merit I create by engaging in generosity and the other far-reaching practices, may I attain Buddhahood for the benefit of others.” When you do that, you can be visualizing the Buddha in the space in front of you, and light coming from the Buddhas and bodhisattvas while thinking, “I’m taking, and retaking the bodhisattva vow.”

Audience: So, it’s not like taking the whole vows?

(VTC): No, no, no, no, no, no. Reciting the vows is another thing. Taking them is through one prayer, and there are shorter verses and longer verses in which you say I am making a commitment to practice the deeds of a bodhisattva.

Audience: So, it’s generating the awakening mind by taking them every day.

(VTC): Yes, not just generating the awakening mind, but really making the determination to follow the conduct of a bodhisattva, to engage in the deeds of a bodhisattva.

Audience: Is it that you have to refuse their apology? Or is it like something else—you can’t accept it or refuse it?

(VTC): So, you’re asking if you’re not really refusing it, but you can’t accept it and need some time to think about it?

Audience: If a person comes to you, and you’re angry or hurt, whatever is in your mind, the anger is still there, and you haven’t really worked that out in your mind, and you can’t really accept it because that’s in your mind, so then you can’t even see their sincerity. Whether it’s there or not, you can’t even see it.

(VTC): You’re saying that you’re still actively holding onto anger even though somebody’s apologizing to you.

Audience: Yes.

(VTC): That’s the thing: you’re not on top of it, and that’s how this gets transgressed, because we’re not on top of it. We’re not willing at that moment to say to ourselves, “Oh, I need to really consider this and try and let it go.” If we’re saying to ourselves, “Oh my goodness, they apologized. I thought this would never happen in my whole life. I’ve never even thought about letting this go because I never thought they would apologize, and here they are apologizing” then you may not be completely free of your anger yet, but you’re really going in that direction. You’re appreciating their apology. But when you’re still hanging onto it with so much resentment that you can’t really take their apology in then it’s refusing the apology.

Audience: [Inaudible].

(VTC): At the time when you couldn’t accept their apology, that’s not accepting the apology. Then, later, when you change your mind and you really feel grateful to them, they don’t know that you have. It would be nice to contact them and let them know that you changed your mind, and that you really appreciate their apology after all. I’m sure that would make a big difference to the other person.

Audience: Does that purify the transgression?

(VTC): I think you should still do some work purifying. Because you want to make sure you don’t do it again. Part of the thing is putting the habitual tendency in your mind to do it again. So, I think you need to do more than just later decide to accept it. You need to actively try and remind yourself to accept apologies.

Audience: I thought it was interesting about apologies. Wouldn’t it be better not to hold grudges regardless of getting apologies?

(VTC): Yes, and I think that’s what, in some way, it’s pointing to. This precept isn’t saying that you hold the grudge until the person apologizes: “Oh, now finally! You’ve gotten your wits, and you’ve apologized. I accept it.” No, we should be working on our anger all the time and trying to release whatever anger there is so that we can forgive the person whether or not they apologize. If we do that, then if they do come and apologize, it’s very easy to accept it because we’ve already worked on it ourselves, and we forgive the person.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Uh-huh, but in some way, that’s what it’s getting at. The real transgression occurs when they apologize, and we refuse it. The thing it’s getting at is not forgiving and holding onto the anger in any situation, especially if somebody is apologizing.

Audience: With the pratimoksha vows, if you break one of those, that’s it, you lose it?

(VTC): If it’s a root pratimoksha and you break it with all the parts complete then you lose it.

Audience: So, what is a root pratimoksha vow?

(VTC): Well, it’s not important for you to know that in terms of the monks’ and nuns’ vows. In terms of the five lay precepts, they would be killing—intentionally killing a human being who dies before you—and so on. It would be stealing something that does not belong to you in any way, that is of the amount that the government would get involved, the legal system would get involved—taking it and making it your own and really delighting in that. The third one, unwise and unkind sexual conduct, is principally if you’re in a relationship. It means going outside of that relationship, or even if you’re not in a relationship, going with somebody who is in one. The lying one is particularly lying about your spiritual attainments. The one of intoxicants is not a root one, so if you drink intoxicants, you don’t lose your five lay precepts. With the five lay precepts, if you break it from the root, many teachers will let you retake them. But with the monastic vows, we’re finished; there is no possibility of retaking them.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.