The precepts of aspiring bodhicitta

Part of a series of talks on the bodhisattva ethical restraints. The talks from January 3 through March 1, 2012, are concurrent with the 2011-2012 Vajrasattva Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey.

- Beginning the explanation of the bodhisattva ethical restraints (vows)

- The precepts of aspiring bodhicitta

- How to protect your bodhicitta from degenerating in this life

- How to prevent being separated from bodhicitta in future lives

- Abandon the four harmful actions

- Practice the four constructive actions

Bodhisattva ethical restraints 01: Precepts of aspiring bodhicitta (download)

The eight precepts of aspiring bodhicitta

Since this is aspiring bodhicitta, I thought I would go through some of the precepts for aspiring bodhicitta, in case people forgot to look them over or didn’t even know they had them.

There are eight precepts of aspiring bodhicitta. There’s first a set of four and then there’s two more sets of four that are combined to make one set of four, but they’re expressed as two sets of four. The goal of these precepts is to protect our bodhicitta, so it doesn’t decline in this and future lives.

How to protect one’s dedicated heart from degenerating in this life

We certainly don’t want it to degenerate in this life. First,

Remember the advantages of bodhicitta again and again.

You’ll see throughout the Lamrim there’s always sections on what’s the advantage of this and what’s the advantage of this and what’s the disadvantage of this. The Buddha really explains to us what the advantages of something are so that we’ll have some enthusiasm to go and generate it in our mind. This is the same strategy that a car salesman uses, or a laundry soap salesperson, or whatever it is: “Here’s the advantage.” And we go, “Oh yeah, if I use this toothpaste then this is going to happen and that’s going to happen,” and we completely let this rubbish propaganda influence us. But we don’t spend time thinking of the advantages of bodhicitta. This is what we should actually spend our time thinking of. This is explained in the lamrim. I’m not going to tell you now; you can look it up. It may be good to think about it a little bit, see what you come up with, and then compare it to the text.

Then, The second one:

To strengthen our bodhicitta, generate the thought to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings three times in the morning and three times in the evening. Recitation and contemplation of the prayer for taking refuge and generating bodhicitta is a good way to fulfill this.

The refuge and bodhicitta prayer that we did is actually verse A1 in the Six Session Guru Yoga. Verse A1 is refuge, and it’s bodhicitta. If you think properly, when we say, “By engaging in generosity and the other far-reaching practices, may I attain awakening for the benefit of all sentient beings,” that could be generating aspiring bodhicitta. That could also be generating engaging bodhicitta. So, there’s that way to do it, but here in the Six Session Guru Yoga we’re doing verse A3, and that’s generating the aspiring bodhicitta. We do this three times in the morning and three times in the evening.

And then three:

Do not give up working for sentient beings even when they are harmful.

It’s very easy to give up working for sentient beings. We get really, really mad at somebody, and we say, “Forget this sentient being! They’re incorrigible! There’s nothing I can do to help them. They don’t listen to me, for god’s sake—or for Buddha’s sake either. They don’t listen to me, and I’ve been trying to benefit them—in other words, control them—for a long time, and they just aren’t following!” It’s very easy to get discouraged, to get fed up, to say, “Forget this sentient being.” Or when we get really mad, we might say, “Forget all sentient beings.” Just forget them all; they’re a nuisance. They’re a pain in the neck. I just want liberation so I can get away from them. It sounds like the motivation to take drugs, or drink, doesn’t it? “The people around me are a pain in the neck. I can’t stand them. I want to get away from them”: glug, glug, puff, puff, pop, pop. But you can see that motivation doesn’t work. So, it’s important not to give up our love and compassion for sentient beings.

And then the fourth one is:

To enhance one’s bodhicitta, accumulate both merit and wisdom continuously.

Try and do practices that accumulate merit: offering mandala, making offerings—things like this, these kinds of actions. And also accumulate wisdom: meditate on dependent arising and emptiness. Both of those will act as things that support our bodhicitta. Even though this is aspiring bodhicitta—it’s not yet engaged bodhicitta—we still need to support it. If we lose aspiring bodhicitta, then forget engaged bodhicitta; it’s impossible.

Preventing separation from bodhicitta in future lives

The first four protect us from letting our bodhicitta degenerate in this life. But we also want to act in ways so that we can encounter bodhicitta in future lives and encounter teachers who will teach us bodhicitta. We shouldn’t take it for granted. How many people on this planet have never even heard of bodhicitta? So, if we really want to encounter it and learn about it in future lives, then we need to create some karma to do that in this lifetime.

So, the four remaining precepts are in two complementary sets of four. These help us to not be separated from bodhicitta in future lives.

Abandon four harmful actions

The first on is:

Deceiving our Guru, our abbot, or other holy beings with lies.

This one is also easy to do. It’s like if our teacher asks us a question and we feel embarrassed because we didn’t follow the instructions or this, that, or the other thing, so we kind of fudge the truth. It’s not so difficult to do that. But when we lie to our teacher, our abbots, or to holy beings, are we really protecting ourselves, or are we harming ourselves? We’re doing it because we want to protect our reputation. Is having our teachers think well of us our goal? Is that our goal in the relationship? “Yes! I want to be popular; I want to be liked; I want to be smiled at and accepted and said sweet words to and praised and approved of and everything else!” That’s it, isn’t it?

Is that the proper motivation? No! It’s our motivation, but is it the proper motivation? No! Our motivation should be to form a relationship whereby we’re trusting this person to guide us on the path. And to guide us on the path they may need to correct us, they may need to reprimand us, they give us teachings, whatever it is. But if we’re trying to look good in front of them and we’re not being truthful, then how are they going to benefit us if we’re putting on a front? Finally we met somebody who really wants to benefit us, who’s not just a fair-weather friend or attracted to us because we’re good-looking or funny or have money or whatever it is—we finally met somebody who really cares for us, but what do we do? We lie to them. Who’s getting hurt when we do that? Ourselves. The point is not about having a good image in front of our teacher. The point is to be open and honest so our teachers can help us.

Audience: In relation to this precept, I’m wondering about active deception versus passive deception. Like when someone is put on the stand and they vow to tell the truth, the whole truth. So, it’s a situation where you might think, “I’m not sure how they’d feel about that,” or you think your teacher might disapprove of it, so it never comes up.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): And you’re going to make sure it never comes up.

Audience: It’s not like lying; it’s not like directly lying when things are asked to you in which case you would tell. It’s more like, “No, I’m not going to go there…”

(VTC): Okay, so it’s the kind of thing where you’re not sure how your teacher would really feel about something, but you don’t bring it up and you make sure they don’t bring it up. If they did, you would probably kind of…

Audience: Make a joke.

(VTC): Exactly. You would make a joke or wiggle out of it one way or another. This is when we do something so we don’t have to answer the question, or do this, that, or the other thing. But it’s interesting, when we have that thing in the back of our mind about, “Maybe I’m doing something that isn’t really good for me on the path,” and we don’t want out teacher to find out about it, that’s a very good example of relating to our teacher as an authority figure. “What they don’t know won’t hurt them, and they can’t disapprove of me.” But what our attitude should be is, “I’m doing something, and I’m not so sure if it’s something that’s really conducive to get me where I want to go on the path to enlightenment.” If I’m really unsure if doing this is going to get me where I want to go, then I should ask somebody who can clear it up for me and tell me whether this action is something that will help me on the path or hinder me on the path. But why don’t we ask that question? Because our motivation isn’t really to progress on the path; it’s to look good.

Audience: Or we already know the answer and don’t want to hear it.

(VTC): Exactly, we know the answer and we don’t want to hear it—or who knows what it is.

Audience: We’re afraid of what the answer might be.

(VTC): But that again is because we’re afraid of what the answer might be. Even if our teacher tells us to do something, our mind instantly reacts with “I can’t do that!” You have to see if it’s “I can’t do that” or “I don’t want to do that.” Or we have to see if it’s, “Gee, I aspire to do that but it’s beyond my capability right now.” In which case that’s fine. I aspire to do that, and it’s beyond my capability, but I hold that aspiration. Or you might be thinking “That is interfering with my pleasure, and I don’t want to hear anything that interferes with my pleasure.”

The second one to abandon is:

Causing others to regret virtuous actions that they have done.

This is another one that is easy to do. When someone has done a virtuous action, maybe we’re jealous of them because they did it and we didn’t. Or maybe we wanted their attention, and they were putting their attention somewhere else doing this virtuous action. Or we wanted their resources, but they gave their resources to somebody else. There are all sorts of ways in which we may subtly, or not so subtly, discourage somebody who has done something virtuous—because it interferes with us getting what we want, or it interferes with our ideas.

For example, there was this Maitreya Buddha statue that they want to build in India. His Holiness was saying that it’s very good, in all these Buddhist pilgrimage places, if we also helped the native population. The people who live there are often very poor, or landless, or ill, or whatever. So, somebody went to Khensur Jampa Tegchok and said, “Well, don’t you think that instead of building this statue they should build hospitals and clinics and things like this?” And Khensur Rinpoche just said, “His Holiness said that it would be nice to benefit the people in the community.” And the person said again, “But don’t you think it would be good, rather than doing that to do this?” And Khensur Rinpoche just repeated again, “His Holiness said that it would be good to benefit the people in the community.” Building the Maitreya Buddha statue is a virtuous action, so he certainly wasn’t going to tell somebody, “Don’t do that.”

It may be that some people prefer to use their money to help sentient beings rather than build statues. That’s up to that individual’s personal choice. Rinpoche wasn’t going to tell them this, that, or the other thing. But he also wasn’t going to tell them that building the statue was bad, or that they shouldn’t donate to that. Some of these things can be quite subtle sometimes. It’s important to not discourage somebody who has done something virtuous, like, “Why do you want to go on that long retreat? Go on a shorter retreat, then we can go on holiday afterwards.” Or saying, “Why do you want to give that donation to them? We can use the money for ourselves.” This means to really not impede other people’s wish to do virtue: “Don’t do your meditation session now, do it later. Let’s go out to dinner now.” And when we come back at 10:00 PM you’ll be too tired then, but never mind.

Then the third one is:

Abusing or criticizing bodhisattvas or the Mahayana.

They say since we don’t know who’s a bodhisattva and who isn’t, it’s better not to criticize anybody. Now, what does this actually mean—not criticizing bodhisattvas—and why is this so bad? Well, if we criticize a bodhisattva who’s working for the benefit of sentient beings, it’s like criticizing an action that is being done for the benefit of sentient beings. And since we as aspiring bodhisattvas, according to this verse, and we want sentient beings to benefit then we don’t want to interfere with the actions of somebody who is doing that. Now, does that mean that we never say anything? Is it like: “I don’t know who’s a bodhisattva and who isn’t, so I never say anything. I know all sorts of who-knows-what’s-going-on, but I don’t say anything”? No, it doesn’t mean that.

There are times when all sorts of weird things are going on and we need to bring it up and talk about it, but we need to do it at the proper time, to the proper people, and without being angry and judgmental. But it’s important to talk about it for the benefit of the people involved. This is true even if it is somebody who is a Dharma teacher or who is this, that, or the other thing, or has the reputation of being somebody who has the title of being a tulku or a Rinpoche. If something is going on that is against the general Buddhist precepts, we have every right to bring it up to them or bring it up to whoever it is, in a Dharma Center, or whatever. But we don’t do it with the motivation of bad-rapping that person, grinding them into the dirt, and ruining them, because that’s a motivation of anger.

I’ll just relay a little incident I had with Lama Yeshe as an example. He would come to the Dharma centers once a year, once every other year, once every three or four years, and all sorts of people would come and talk to him for advice, but he needed to know what was going on in the Center. I remember once he was asking me questions about some people and what they were doing, and I didn’t want to say anything because they were doing something that I didn’t think was so wise, and I didn’t want to criticize anybody to my teacher. Lama kept asking in different ways, and finally I said, “You know, I really don’t want to criticize anybody.” And he said, “There are times when you need to tell what somebody’s doing so that somebody else can step in and help them.” So then I told him. There are different situations where we need to say something so that somebody else can get help. One of our root Bhikshuni downfalls is if another Bhikshuni has committed a root downfall, and we don’t say anything about it. We need to speak so that other people have the opportunity to purify things. But that’s very different from criticizing somebody with an angry, judgmental mind and the intention to really trash them.

Then the fourth one is:

Not acting with a pure selfless wish but with pretension and deceit.

Instead of acting with a pure, selfless wish and wanting to benefit others, this is when we act with pretension and deceit. We should abandon doing that. Pretension and deceit are two of the auxiliary negative mental factors. With pretension, we pretend to have good qualities that we don’t have, and with deceit, we pretend not to have bad qualities that we do have. Instead of really having a pure, selfless heart and acting accordingly, we’re pretending to be some great bodhisattva just so we can get reputation or offerings or something and look good.

Or we’re covering up our faults and pretending not to have certain negative qualities, negative traits—again, so that we look good. Here, as much as possible, we try and have a pure, selfless wish. Sometimes it’s really hard and we don’t have one. If we don’t have a pure, selfless wish, at least don’t put on a show pretending to have one. At least let’s not have pretension and deceit. Maybe we just have to be honest and say, “Well, if I were a bodhisattva, I would really have a pure, selfless wish about this, but I’m not. And this is the best I can do at this particular moment, and I aspire to do better in the future.” That’s much better than putting on a song and dance show pretending to be something that we’re not.

I have to confess something I did last year. When the alarm rang at a quarter to five in the morning, sometimes I would get up, turn on the light, and then go back to sleep for five minutes, then press the alarm again, another five minutes, press it again, and probably got another ten or fifteen minutes of sleep—with the light on so everybody would think I was awake. I am not doing that this year. Of course, just because you don’t see the light doesn’t mean I’m not up, because I often meditate without the light on. But you can be sure that if it’s a quarter to five this year and the light’s on, I’m out of bed.

Practice four constructive actions

The four constructive actions that we want to practice, which are the opposite of these, are:

Abandon deliberately deceiving and lying to Gurus, abbots, holy beings, and so forth. Be straightforward, without pretension or deceit.

Number one on the “to do” list corresponds to number one on the “don’t do” list. Number two on the “do” list corresponds to number four on the “abandon” list. So, this first one is to practice being straightforward without pretension or deceit.

And then three:

Generate the recognition of bodhisattvas as one’s teacher and praise them.

That counteracts criticizing bodhisattvas or the Mahayana. And then the fourth is:

Assume the responsibility oneself to lead all sentient beings to enlightenment.

That counteracts the second one to abandon, which is causing others to regret virtuous actions that they’ve done. When we cause them to regret virtuous actions that they’ve done then we’re leading them away from awakening. When we assume the responsibility to lead them to awakening then we’re doing the opposite of that.

When we really look at these closely, they can be difficult to do, can’t they? And yet, this is just the aspiring bodhicitta. But this is the whole reason why there are these guidelines, so that we know what to practice and what to abandon. And we have them so that we can train our minds in doing this. So, we should be really happy thinking, “Now I know what to do, how to train my mind,” instead of thinking, “These are too difficult; I can’t do them.“ These as things we are practicing, that we are training our body, speech, and mind to do, if we take them like that and remember them all the time then slowly we actually do train our body, speech, and mind.

Any questions so far?

Audience: (Inaudible)

(VTC): Are you referring to the refuge guidelines or the root tantra? It’s the root tantra? With the root tantra, what we’re trying to do is not make best friends of people who criticize the tantra and criticize our tantric masters. That doesn’t mean we give up working for their benefit. It just means that because our minds are not very strong, we don’t become best friends with the people who are going to criticize our chosen spiritual practice because we could be adversely influenced by them. This comes up in the refuge precepts as well. But that doesn’t mean we lack compassion for these people; it doesn’t mean we don’t work for their benefit. We can still work for their benefit and still have compassion for them but without being really close in a way that we can be adversely influenced by them because our own minds are conflicted—we want to be popular, and we want people to approve of us and like us.

Generating bodhicitta

Then Verse A4 is from Shantideva. I believe it’s in chapter three. This and the next two verses are actually from Shantideva.

Spiritual Masters, Buddhas and bodhisattvas: please listen to what I now say from the depths of my heart. Just as the sugatas of the past have generated bodhicitta, and just as they dwelled in the progressive trainings of the bodhisattvas, so I, too, for the sake of benefiting migrating beings, will generate bodhicitta and will practice the progressive trainings of the bodhisattvas.

Sugatas are those gone to bliss; it means the buddhas. In other words, just as they went through the ten far-reaching practices, those progressive trainings, we, too, aspire to benefit migrating beings instead of just wanting to look good.

All the buddhas and sugatas and tathagatas of the past, how did they attain full awakening? It was through practicing the ten far-reaching practices and all the other practices and trainings of a bodhisattva. So, just as they practiced that way and became buddhas, I’m going to do the same practice that they did. We do this, saying it very clearly in front of the whole visualization of the refuge field with Shakyamuni Buddha and all the lineage lamas, and all the buddhas and bodhisattvas and arhats and dakas and dakinis and protectors and so on. We’re saying this in their presence; they’re being witnesses to us saying something from the depth of the heart. As we say here, “I say it now from the depths of my heart,” it’s important to really, every day, renew our bodhicitta in this way. This is actually one of the commitments of bodhicitta.

If we look at our bodhisattva trainings, one of them is to generate bodhicitta repeatedly in the day and the evening. This is fulfilling it here. This is the engaging bodhicitta, and so we imagine when we’re saying it that we are again receiving the bodhisattva ethical restraints. I don’t want to call them vows because people misconstrue the meaning of the word vow. But it means that we’re again recommitting ourselves and imagining re-receiving the bodhisattva ethical restraints in the presence of all the buddhas and bodhisattvas, with all the sentient beings looking on. When we do the visualization clearly and really think about what we’re doing, it’s very, very moving to do this. And we do it every morning and every evening. Our bodhicitta really becomes firm in this way.

And then we take our commitment to try and become a buddha for the benefit of sentient beings seriously, and it’s not just a flippant kind of thing that we were saying because it sounds good, or we were emotional that day or whatever it is. We’re retaking this every day. And in this way, by doing it and imagining that the light comes from all the buddhas and bodhisattvas into us and that the light is the nature of the bodhisattva ethical restraints, then we really feel: “Okay, I’m taking them again, and now they’re pure again, and I’m starting afresh again. And now I’m going to go forward with that same kind of enthusiasm I had the first time I took the bodhisattva restraints.” So then you feel really good, and all the sentient beings are around you going, “Right on!” And all the buddhas and bodhisattvas in front of you are going, “Far out!” And then, after we do that, in the next two verses we rejoice.

Rejoicing

Having attained an endowed human rebirth now, my life has become fruitful. Today I have been born in the Buddha’s family and have become the Buddha’s spiritual child.

So now our human life has become really precious. I remember one of my teachers saying, “The fact that our mother had to go through labor pains and everything she went through to deliver us, now it actually has some meaning because we’ve taken the bodhisattva ethical restraints.” Now what our mother did was worthwhile—everything she went through. So it’s important to really think about that: “And now my life has become fruitful.” We’re thinking “My life is now meaningful. I’ve been born into the Buddha’s family and have become the Buddha’s spiritual child” in the sense that I will grow up, on my spiritual journey, to become like the Buddha. I’m the child that’s going to grow up to become the adult.

We can feel really happy about our lives: “Wow, my life has not been wasted. I’m not perfect, but wow, my life is meaningful, and it has purpose. I’ve done something really good. And I rejoice.” It’s very important to really rejoice instead of thinking, “I just took them, and I can’t keep them, what am I going to do? This is too hard!” Because that whole thing is just a thought, and it’s a self-sabotaging thought. It’s a thought of pure, unadulterated nonsense. So, get rid of it.

Otherwise, it’s like you’re saying, “Shantideva, look: you are lying. My life has not become meaningful and purposeful because I took the bodhisattva vows. I’m just this degenerate beep-beep-beep who can’t do anything, and what you’re telling me is a lie.” Do you want to say that to Shantideva? Do you really want to tell him that he doesn’t know what he’s talking about—that this is too hard, and you can’t do it, and your life is meaningless? Think about it, because we get into those kinds of mental states sometimes, don’t we? Think about it. If Shantideva were right here in front of me, if Buddha were right here in front of me, would I really say, “You’re lying”? I hope not. It’s important to really see that all these self-deprecating, self-sabotaging thoughts are just that: self-deprecating, self-sabotaging lies. It’s not the Buddha who’s lying; it’s our own self-centered mind that’s lying.

Conscientiousness

So, A5 was taking joy in bodhicitta. Then A6:

From now on, whatever happens, I will act in accordance with this family and will never sully this faultless and pure family.

This is meditating on conscientiousness: “I took the bodhisattva ethical restraints. I want to be conscientious, and I value virtue. It’s something important to me, and so I’m going to be conscientious about this and not act in ways that bring disgrace to the buddhas and bodhisattvas.” In an Asian culture, the group identity is very much an identity of the family. So, you don’t do anything that brings disgrace upon your family, because you are part of this group and part of this group identity. You take it very seriously. In the west we say, “Forget group identity, forget my family; I don’t care if I disgrace them or not. I moved out of the house a long time ago, and anyway, they were all alcoholics.”

We need to have a different way of thinking. We need to see that we have entered the Buddha’s family in this way—by taking the precepts. We have some responsibility. We have not just responsibility to other people; we have responsibility to our own selves, our own integrity, and our own conscientiousness. We have a responsibility to act in accord, as much as we are capable of doing, with what we said we’re going to do. Of course, as I always say, if we really could keep the precepts perfectly, we wouldn’t need to take them. We all know that we can’t keep them perfectly, but here what we’re doing is encouraging ourselves so that we try and do the best that we can. And that’s what’s important—that we just do the best that we can. When we make mistakes, we pick ourselves up and try again. And this is telling us to really feel quite happy because “Now my life has become meaningful.”

When you think about it, it’s true, isn’t it? What a fantastic way to spend our life: to try and generate this intention. And even if our bodhicitta is contrived or fabricated, the fact that we respect and treasure bodhicitta and think it’s a good thing, that’s really swimming upstream from what the self-centered mind tells us to do. And it’s contrary to what most of our culture tells us to do with all the magazines called Self and I and this kind of thing. We should really treasure that. We should respect that part of ourselves that wants to practice in this way. Let’s rejoice at how fortunate we are to be able to practice this way.

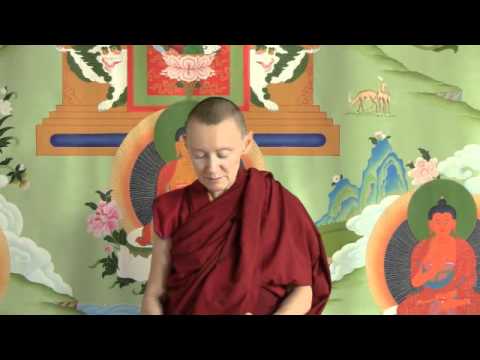

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.