The best antidote

Part of a series of teachings on a set of verses from the text Wisdom of the Kadam Masters.

- The importance of applying specific antidotes to the afflictions

- How the wisdom realizing emptiness is the general antidote for all of the afflictions

- Examining how all phenomena are dependent arisings and are empty of inherent existence

Wisdom of the Kadam Masters: The best antidote (download)

The next line is,

The best antidote is the recognition that everything is devoid of intrinsic existence.

What this means is we have our disturbing emotions (like anger, attachment, jealousy, laziness, lack of integrity, spite, and all sorts of delightful things like that) that we need to apply antidotes to. When afflictions come in our mind it’s not just a question of ignoring them and waiting until they go away. Sometimes we can do that, but that doesn’t really solve the problem because if we think about the situation again a little bit later we’re going to get angry again, or get greedy again, or something like that. So in the Tibetan tradition we mainly focus on applying an antidote, in other words, generating another state of mind that is the opposite to that disturbing emotion.

In the case of getting angry we generate fortitude and love. In the case of cruelty or violence we generate compassion. In the case of greed or attachment we meditate on impermanence or the benefits of generosity, or something like that. In the case of ignorance of karma and its effects then we contemplate how karma and its effects, that law, works.

These are individual antidotes that apply specifically to individual afflictions that we have. But there’s one antidote that is the best one (that we’re talking about here) which applies universally to all the various afflictive states we have, and that’s the understanding that all things lack any kind of inherent (or intrinsic) nature.

In 25 words or more…. [laughter] …what that means (it’s difficult to give a short explanation of this) is that things, the way they appear to our senses, is they appear to be very real objects out there. They appear to be something out there, unrelated to us. This is a table. This is a recorder. This is the color red. This is the carpet. This is a wall. Or the ceiling. Or whatever. It looks like all these things exist external to us and have no relationship to our mind, except we just happen to be walking along and contact them. So they appear to be very independent to us. They don’t appear to depend on our mind, to depend on our perspective, on how we look at things, on what we call them.

But when we actually analyze a bit deeper we see that things are very, very dependent. We call this a wall for a certain reason, don’t we? If those same pieces of faswall (that’s the material it’s made out of) were laid flat we might call it a floor. But when those materials are laid perpendicular like this (or vertical) then they’re called a wall. If the building’s partially destroyed those bricks may still be standing there, but are they a wall? Doesn’t a wall have to hold up something? [listens to audience input] Okay, so maybe it’s still a wall. It’s no longer the wall of a house, for sure. In fact, it might be considered a mess instead of even a wall.

Without the rest of the building would this be a floor? Or do you have to have the rest of the building to have a floor? Without you existing would there be me? In other words, if nobody else existed, would we say “I”? Would we say “me”? Or is “me” always in relationship to somebody else: “me” and “others.”

Right now, what do we have for lunch? Soup is a good example. When you have soup, soup comes from many different things, doesn’t it? You have to have carrots and celery and potatoes and whatever else you choose to put in the soup. But is the soup any of the vegetables? Is the soup the broth? What exactly is the soup? What do you think the soup is? [listens to audience input] The carrots would be part of the soup, but it’s not the complete soup, is it? Is there anything that is the complete soup?

[To (young person in) audience] When you look at who you are, who’s Miranda? Can you point to who Miranda is? Is Miranda a chin? Who’s Miranda? [listens] A complete product of what? What do you need to make “Miranda”? [listens] You need a body. What else do you need? [listens] She wouldn’t be a sister without having a sister. [listens] You need your body. Do you need your mind, too, to have Miranda? You need all your feelings, don’t you? And all your thoughts, and all those kinds of things. Because if there was just the body of Miranda, I don’t think we’d call it Miranda. It’s interesting when you think about something. [listens to audience] [laughter] But he wouldn’t be a father without you.

When we look at things, things exist dependent on other things. They don’t exist on their own. Right now you’re students. But you’re students because there’s a school, because there’s the teacher. You can’t be a student without there being a school and without there being teachers, can you?

Everything we are, everything we look at, depends on something else. It either depends on (for example) the teacher and student, or parent and teacher, like that. Or it can depend on its parts. (For example) we look at the recorder, and the recorder is just a bunch of parts put together in a certain way. Isn’t it? Are any of the parts the recorder? No. But is it strange that you put together a bunch of parts that are not a recorder, but you get a recorder from doing that? Does that seem odd? Because all the parts are not a recorder. How can you put together a bunch of things that aren’t a recorder and get a recorder? How does that work?

Can you put together a bunch of oranges and get an apple? No. Then how come we can put a bunch of things that aren’t a recorder together and have it be a recorder? That seems rather strange, doesn’t it?

What makes it a recorder? [To audience] Dad [of the two young girls in the audience] you can answer this one. We call it a recorder, and we have a definition for recorder, and it fits the definition of recorder. But it’s strange, because all the parts are not a recorder, and if you put all the parts together in front of you like this they’re still not a recorder. They’re only a recorder when you put them all together in a certain way.

[In response to audience] A flower, right. Think about that one.

Or think about the soup. You take out the potatoes, you take out the carrots, you take out the broth, where did the soup go? When did it stop being a soup?

What we’re getting at here is that everything’s dependent on other things. And when we see the world as things being dependent then our view is much more flexible than when we see things as being very solid and concrete, as existing out there objectively, not in relationship to us or in relationship to anything else.

So, that “best recognition” is the recognition that they lack any kind of objective, or intrinsic, existence.

It’s very interesting, very good meditation to do when you eat lunch. You put salad on your plate, then you think, “What makes this salad? Why do I say there’s salad on my plate?” What makes it salad?

What else do we have? [Looking at the table, where lunch is set up.] Tofu. What makes something tofu? It’s quite interesting to start, and okay, well there are all these different molecules that make tofu. So which molecule is the tofu? I wonder if there’s only one tofu molecule. Do you think there are a bunch of different molecules together that form tofu? I don’t know. Is there one complex tofu molecule? Or are there many tofu molecules put together? And which one’s the tofu?

Anyway, thinking like this gives us a lot more space in our minds so we don’t react so emotionally to different things.

Like if you’re really attached to something, clinging onto it—”I want this!”—then you look at it and you mentally put it into different parts, and then you say, “Okay, what is it about this that I want?” Something you really want very much, then you break it into different parts, and then, “Hmm? None of these parts looks so good.” Do they? So what is it I’m craving?

It’s a very good antidote, like that.

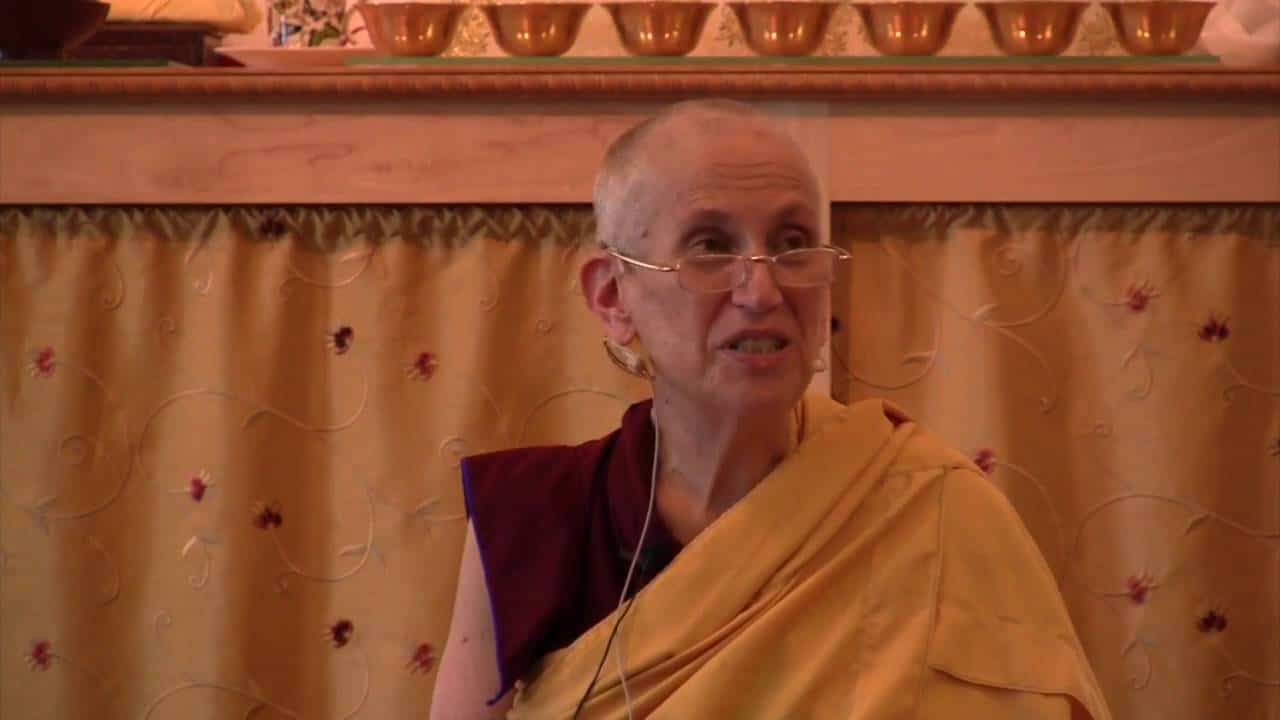

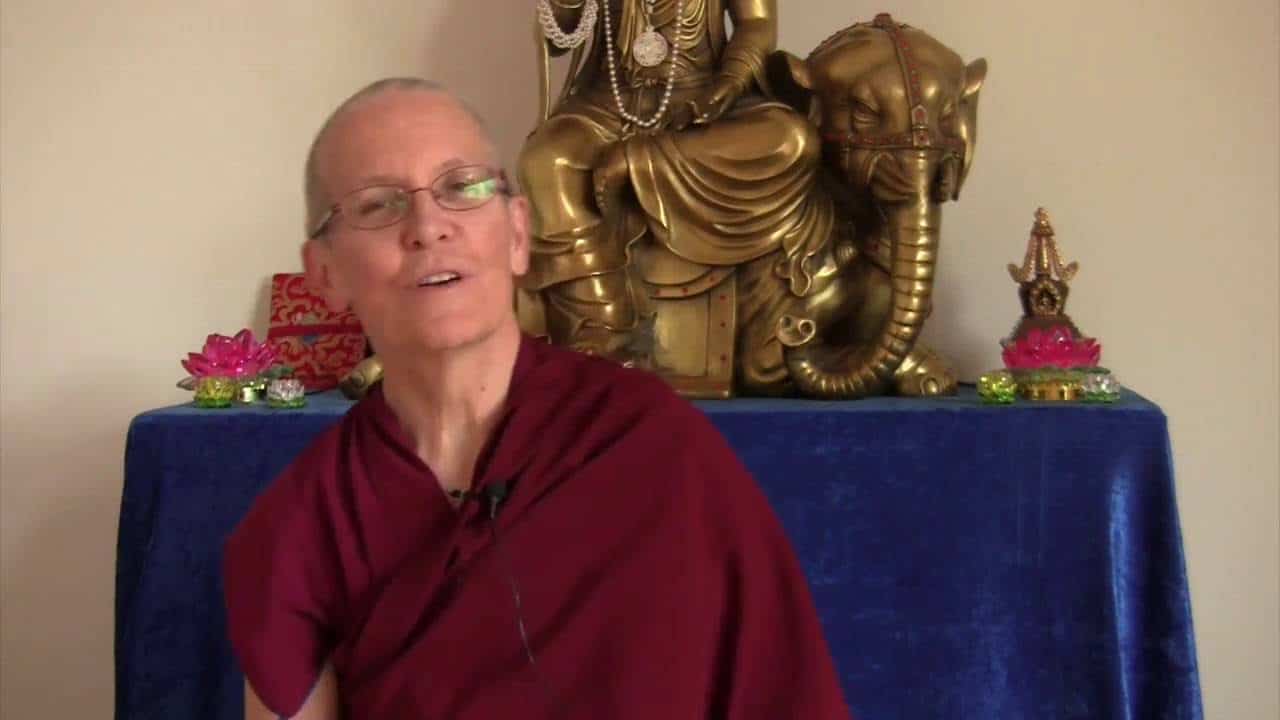

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.