Emptiness and the self

Part of a series of teachings on His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s book titled How to See Yourself as You Really Are given during a weekend retreat at Sravasti Abbey in 2016.

- The example of a car and its parts, and how it applies to the person

- The two meanings of “self” that must be differentiated

- Name-only

- The four-point analysis

- Questions and answers

We will continue on with chapter 11, which is entitled: “Realizing that you do not exist in and of yourself.” When he talks of “existing in and of yourself” or “being established as its own reality,” all of those are synonyms for inherent or independent existence. In other words, it means that something has its own essence, it can set itself up; it exists independent of all other phenomena, all other factors. All those terms mean the same thing.

He starts with a quotation from the Buddha:

Just as a chariot is verbalized [designated]

in dependence on that collection of parts,

so conventionally a sentient being

is set up depending on the mental and physical aggregates.

This example of a chariot is used quite a bit, actually. You find it in the Pāli Canon and then also in the Questions to King Milindra, and it is also in the Sanskrit scriptures. I guess a chariot was a luxury item in ancient India, something very easy to get attached to. This is kind of like your red sports car when you are 45 years old, or whatever your thing is. Maybe it’s chocolate, or whatever your big object to attachment is. Maybe we will use a car because people have cars, and you get attached to your car, don’t you?

When we look to see a car there, it looks like it is just a car. There is a car. Any idiot knows that’s a car. That’s how the car appear to us, as if it is an objective entity out there, as if it set itself up, as if it’s not dependent on anything. Everybody knows it’s a car. It has car essence that radiates from it. But actually when you look, if you start to take the car apart—you have a hood, and a roof, a windshield, and an axle, and pistons, and an engine, spark plugs and wheels, and I don’t know all these other terms, but there knobs to pull the windows down, and the place to hang your cup. It has mechanical parts, it has seats, it has doors, it has windows, and it has a dashboard. If you take your car and start separating all these parts and laying them all out, where is your car? The dashboard is over there, and one wheel, two wheels, three wheels, four wheels, an axle over there and dashboard over there, your cup holder in the center—because that’s the most important part—and the steering wheel. So, when you separate all the parts, do you have a car?

Audience: No

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): No. They are the same parts that are there when you have a car. You haven’t taken away any parts, and you haven’t added any parts, but the arrangement of the car parts is such that our mind no longer looks at them and says, “There is a car.” Having parts scattered all over the place cannot drive you anywhere. Those same parts are not a car—individually or collectively—but when you put them together in a certain form, all of a sudden you have a car. And it seems as if car popped up from the side of the parts or the collection of parts, but it couldn’t have because it’s the same parts that were there when they were spread out, and it wasn’t a car then. So how does the perception of a car come up? We have the conception of a car and we give it a label, and then we forget that we were the ones that created it by giving it a label. Instead it appears to exist from its own side.

Just as a car exists by being merely designated on the basis of that arrangement of the car parts—called the basis of designation—the car exists only by being merely designated in dependence upon the basis of designation. In the same way, what we call me or I or person comes about in the same way. You have all the different physical parts of the body, throw in a consciousness, and if it walks and talks and snores, then we say ‘person,’ or “There is Joe.” But actually, there is nothing in that collection of things that is Joe from its own side. Joe came into being because, on the basis of that collection, we looked at it and said, “Oh, there is a person, and we will call him Joe.” We could’ve called him Muhammad, we could have called him Moses, we could’ve called him Roberto, we could have called him anything. It’s just a name, but the conception of there being a person there came about from us.

The analogy with the car makes sense, right? You can see how the car came about just by being merely designated in dependence on the collection of parts. You don’t feel too uncomfortable with that. When you talk about yourself being merely designated depending on the collection of parts, you don’t feel too comfortable with that. “What do you mean I am merely designated in dependence on a collection of parts? I’m me! I’m here, parts or no parts. I am here, and I’m in command?” Isn’t that how we feel? And yet when we analyze, there is no difference between the example of the car and the example of me. The difference is that we really grasp at me, don’t we?

Two meanings of self in Buddhism

In Buddhism the term self has two meanings that must be differentiated in order to avoid confusion. One meaning of self is ‘person’ or ‘living being.’

This is important. I, me, person, living being, whatever—that’s one type of self.

This is the being who loves and hates, who performs actions and accumulates good and bad karma, who experiences the fruits of those actions, who is born in cyclic existence, who cultivates spiritual paths and so on.

Oneself is just that conventionally existing person. The other meaning of self is in words like self of phenomena, self of person, or selflessness.

The other meaning of self occurs in the term selflessness, where it refers to a falsely imagined over-concretized status of existence called ‘inherent existence.’ The ignorance that adheres or holds to such an exaggeration is indeed the source of ruination, the mother of all wrong attitudes—perhaps we could even say devilish. In observing the ‘I’ ……

This is the ‘self,’ the inherent existence that we have put onto objects that they don’t have. Going back to our sunglasses example, this is the darkness that we put on the trees and everything else that they don’t have from their own side.

In observing the ‘I’ that depends on mental and physical attributes, this mind exaggerates it as being inherently existent, despite the fact that the mental and physical aggregates being observed do not contain any such exaggerated being.

Like we just talked about, we put together all the parts of our body and toss in a consciousness and we say, “me,” but nowhere in that collection is there “me” even though we believe there is. “I feel like it exists,” is not a good reason. You learn in Buddhism that, “I feel like it must be this way,” doesn’t count as a reason. If you are looking for something, you have to find it. You can’t just say, “I feel like I have a thousand dollars in my wallet,” and there is going to be a thousand dollars there. You have to be able to locate it.

What is the actual status of a sentient being? Just as a car exists in dependence upon its parts, such as wheels, axles and so forth, so a sentient being is conventionally set-up in dependence upon mind and body. There is no person to be found either separate from the mind and body, or within the mind and body.

We can’t find any person here in the mind and body, and we can’t find any person that’s separate from it either. Because like I said this morning, if you could your body and mind could be here, and you could be on the other side of the room. Does that makes sense? No.

“Name Only”

This is the reason why the “I” and all other phenomena are described in Buddhism as “name only,”

Or another synonym is “merely designated,” or “merely imputed by mind.”

The meaning of this is not that the “I” and other phenomena are just words, since the words for these phenomena do indeed refer to actual objects.

We can’t say a person is a word, and we can’t say a car is a word, so when it says things are “name only,” it doesn’t mean that the person is only a name, because a name can’t walk, talk, and sing and dance, but a person can. So what it means is that they exist by being merely designated.

Audience: Can I ask a question? In the paragraph before, the very last sentence where it says, “there is no person to be found in that separate from mind and body or within mind and body,” it’s really talking about an inherently existent person even though it doesn’t say ‘inherent existent’?

VTC: Yes, but even the conventional person, you can’t find. You can’t find an inherently existent person in the mind and body. The conventionally existent person exists by being merely labeled. You can’t find “it” inside the mind and body either; it’s an appearance. Because if you could find the conventionally existent person in the aggregates, then it would be inherently existent.

Audience: Yes, I understand the words, but that sounds like nihilism, like negating the person.

VTC: No, the person exists by being merely designated, but when you search for the person, you can’t find it.

Audience: I am not comfortable with that.

VTC: I know. That’s why we are not comfortable.

Audience: But we are not looking for the conventional person.

VTC: When we’re doing the four-point analysis, we are examining how the conventional person exists; we are not looking for the inherently existing person. We are examining how the conventional person exists, and it doesn’t exist either in the body or apart from the body, because if it did it would be inherently existent. The conventionally existent person exists by being merely designated. That’s all that’s there. That’s it. It feels incredibly uncomfortable because as soon as we say “I,” it doesn’t seem like it’s just something that exists by being merely labeled but that’s unfindable when you search for it with ultimate analysis. But there is nothing you can find when you search for it. It’s only when you don’t search that there is the appearance of person. When you do search, it’s gone.

Let’s continue a little bit here. This will make us incredibly uncomfortable if it’s beginning to touch home. It makes us incredibly uncomfortable because we are sure that there is something findable there. We are sure! There has got to be something that carries the karma from one life to the next! Our mind says, “You can’t say the person just exists by being merely labeled, because what carries the karma in that case? There is got to be something that carries the karma, not just something that exists by being merely labeled. There has got to be something.” And then we really like the Svātantrika Madhyamikas because they say there is something here. But as soon as you say there is something there, there is no need to designate it. As soon as there is something from its own side, no matter how much from its own side, there is no need to designate it—and it must be inherently existent. But that doesn’t feel right either. This is designed to makes us squirm. Buddhism is not deliberately trying to make us squirm, but it’s our mind that wants to hang on to something; there has to be something there.

The “I,” mind and body

Rather, he said that “since the words for these phenomena do indeed refer to actual objects.” As soon as we hear actual objects, “Oh good, I’m relieved. There is something there. This thermos doesn’t exist just by a name. There is really a thermos there. Yes, that’s comfortable. My reality is back to where it was before.” But no. There is no thermos in this basis.

Rather these phenomena do not exist in of themselves: the term ‘name only’ eliminates the possibility that they are established from the object’s own side.

Established from the object’s own side means that there is something there that makes it what it is. His Holiness is saying that calling it ‘name only’ means that there is not something there that makes it what it is.

We need this reminder because the “I” and other phenomena do not appear to be merely set up by name and thought, quite the contrary. For instance, we say that the Dalai Lama is a monk, a human, and a Tibetan. Doesn’t it not seem that you are saying this not with respect to his body or his mind but about something separate?

You say the Dalai Lama is a monk, a human being, a Tibetan, but do you feel like you are saying that on the basis of his body, or his mind, or something a little bit different from his body and mind?

Without stopping to think about it, it seems that there is a Dalai Lama that is separate from his body and independent even of his mind. Or consider yourself if your name is Jane, for instance, we say, “Jane’s body, Jane’s mind,” so it seems to you that there is a Jane who owns her body and mind and a body and mind that Jane owns.

In other words, Jane is separate from her body and mind.

How can you understand that this perspective is mistaken?

What do you mean mistaken? It’s right!

Focus on the fact that there is nothing within mind and body that can be “I.” Mind and body are empty of a tangible “I.” Rather just as a car is set up in dependence upon its parts and is not even the sum of its parts, so the “I” depends upon the mind and body.

But it is not the body or the mind, or something separate from the body and mind, or the collection of body and mind.

An “I” without depending on the mind and body does not exist,…

“Ok, the “I” depends on body and mind. Good. He’s getting closer. There is something there!”

…whereas an “I” that is understood to be dependent upon mind and body exists in accordance with the conventions of the world.

I will read that whole sentence all together:

An “I” without depending on the mind and body does not exist, whereas an “I” that is understood to be dependent upon the mind and body exists in accordance with the conventions of the world.

Understanding this type of “I” that is not at all to be found within the mind and body and is not even the sum of mind and body, but exist only through the power of its name and our thoughts is helpful as we strive to see ourselves as we really are.

This “I” “exists only through the power of its name and our thoughts.” That’s it! This “I” that we think is so important, that has to get its way, that has to be respected, exists only through the power of its name and our thoughts. There is nothing there on the side of the base. But that is totally contrary to what we see with our eyes, isn’t it? the way we see with our eyes, it is all there—these are speakers, this is cloth, this is a piece of paper, a thermos, gong, tissues, me, you. So, the way things appear even to our eye sense consciousness is erroneous. Remember I told you that Lama Yeshe told us we were already hallucinating, that we didn’t need to take acid? This is what he was talking about. We are hallucinating real people and real objects.

Four steps to realization

There are four major steps towards realizing that you do not exist the way you think you do. I will discuss this briefly first, and then in detail. The first step is to identify the ignorant beliefs that must be refuted.

This sounds really easy—identifying ignorant beliefs. We are smart people. We can identify the ignorant beliefs, no problem! But this is actually the hardest part of the whole thing.

You need to [identify the ignorant beliefs] because when you perform analysis, seeking yourself within mind and body, or separate from mind and body and you do not find it, you could wrongly conclude that you utterly do not exist.

We have to be aware what our ignorant view is and what is appearing to that ignorant view. He is saying that we have to know beforehand that this is the ignorant appearance, that this is the ignorant view, because if we’re not clear about that, when we try to negate inherit existence, we just think that there is nothing there whatsoever—no person at all. That is not what’s happening. This ignorant view exists, but what’s appearing to the ignorant view does not exist. There is a person that exists, but that is not what appears to the ignorance.

Because the “I” appears to our minds to be established in and of itself, when we use analysis to try and find it and it is not found, it seems that the “I” does not exist at all, whereas it is only the independent “I,” the inherently existent “I,” that does not exist.

But you see, our problem is that we can’t tell the difference between the two. Take the sunglasses example. If you have been born with sunglasses, the tree appears to you, but the dark tree is also appearing to you, and you see the dark tree. Can you differentiate between the dark tree and the tree if you’ve never seen a tree without seeing the darkness? No, they look completely molded together, and that’s why this first step is so hard, because we can’t differentiate the wrong view of the “I” from the [inherent] “I” that does exist. That’s why they say that this is really the most difficult step with the whole thing.

Because there is a danger here of stumbling into denial and nihilism, it is crucial as a first step to understand what is being negated in selflessness. How does the “I” appear to your mind? It does not appear to exist through the force of thought;

When you think “me,” think “me, me, me,” do you appear to exist through the power of thought? No. “I don’t exist through the power of thought. I am here!” Isn’t that how we feel? “I am here. I don’t exist just because somebody gave me a name.” We really rebel against that because we are sure there is something in there.

…rather, it appears to exist more concretely. You need to notice and identify this mode of apprehension. It is your target.

That “I” that appears to be there that screams, “Wait a minute! I don’t exist by mere thought! I am in here!” That’s the one. That’s the object that doesn’t exist but feels so strongly like it exists, that thinks if this doesn’t exist, I don’t know what does! I mean that’s how strong we hold it.

The second step is to determine that, if the “I” exists the way it seems to be it must be either one with mind and body or separate from mind and body. After ascertaining that there are no possibilities in the final two steps, you analyzed to see whether the “I” and the mind, body complex can be either one inherently established entity or differently inherently established entities.

After we have some idea of this “I” that’s screaming out, “I exist,” then we have to determine that if the “I” exist as it appears, then I should be able to find who I am. There should be an “I” that I can find. And there are only two places to look for that “I”—either in the mind and body, or separate from the mind and body. So, if the “I” inherently existed, it would have to be either one with the mind and body, or separate from it. There is no other alternative. For a conventionally existent “I,” there are lots of alternatives, but for an inherently existent “I,” there are only these two. This is because with an inherently existent “I,” when we are saying, “I exist,” that’s a strong “I.” If it exists, we must be able to find it. There are only two choices.

A merely labeled “I”—we don’t need to find with ultimately analysis because we are not claiming that’s independently existent. The “I” that exist by being merely named, we don’t need to find through ultimately analysis; we only use conventional language when we are not analyzing. But for an inherently existent one, we’ve got to find it, and we have two choices where it is.

As we will discuss in the following sections, through meditation you gradually will come to understand that there are fallacies with “I” being either of these.

There are fallacies with the “I” being either one and the same with the body and mind, or different from them.

At that point, you can readily realize that an inherently existent “I” is unfounded. This is the realization of selflessness. Then, when you have realized that the “I” does not inherently exist, it is easy to realize that what is “mine” does not inherently exist.

But this is more difficult to realize—when you realize that the “I” doesn’t inherently exist, to establish that the “I” does conventionally exist. And you don’t have a complete understanding of emptiness until you can do that.

The first step, identifying the target

Usually no matter what appears to our minds, it seems to exist from its own side independent of thought.

Does this thermos depend on thought? How does it appear to you, as dependent on thought?

Audience: No.

VTC: No, it appears out there, radiating thermos, the essence of “thermosness,” doesn’t it? If somebody were to tell us that this thermos exists only by name, only because somebody gave it a name, what kind of craziness is that? That’s what we would think. This doesn’t exist just because somebody gave it a name. It has thermos nature in it. That’s how it appears to us. That’s the object of negation—exactly what we perceive every day that we are so sure exists. That’s the thing that doesn’t exist, but it doesn’t mean nothing exists.

When we pay attention to an object whether be yourself, another person, body, mind or material thing, we accept how it appears as if this is its final inner real condition, this can clearly be seen at times of stress, such as when someone else criticizes you for something you have not done. “You ruined this!” You suddenly think very strongly, “I didn’t do that!” and might even shout this at the accuser.”

All day long things are appearing inherently existent to us. But we don’t see that very clearly. His Holiness is saying that at times of either great stress, great anger, or great attachment, those are the times when the appearance of inherent existence is easier to find if we are skillful. It appears clearly then, but even then it’s still not so easy to find because as soon as we start looking for it, it hides. It’s very clever.

How does the “I” appears to your mind in that moment?

Somebody is blaming you for something you didn’t do, like your boss, or your spouse, or somebody you really respect and like. You want that person to think well of you and now that person accuses you of doing something you didn’t do. How do you feel? What’s the appearance of “I” at that moment? “I didn’t do that! Why are you accusing me? The world is against me. It’s unfair!”

How does this “I” that you value and cherish so much seem to exist? How are you apprehending it? By reflecting on these questions, you can get a sense of the way the mind naturally and innately apprehends “I” as existing from its own side, inherently.

This isn’t an intellectual thing. We can say, “Oh, yes, somebody accused me of doing something I didn’t do. The “I” appears very strongly like there is a real, inherently existent me. I am sure that that exists. Now I recognize the object of negation.” That’s just a bunch of words. We haven’t really gotten the feeling for what it is.

Let us take another example, when there is something important you were supposed to do and you discovered that you forgot to do it, you can get angry at your own mind, “Oh awful memory!” When you get angry at your own mind the “I” that is angry and the mind at which you are angry appear to be separate from each other.

They appear to be different, don’t they? Yes. “My stupid mind!”

The same thing happens when you get upset with your body or part of your body, such as your hand. The “I” that is angry seems to have its own being, in and of itself, distinct from the body at which you are angry. On such occasions, you can observe how the “I” seems to stand by itself as if it is self-instituting, as if it is established by way of its own character. To such a consciousness, the “I” does not appear to be set-up in dependence upon mind and body.

Can you remember a time when you did something awful?

Let’s do this. Remember a time when you did something awful. You got it?

…and your mind thought “I really made a mess of things.” At that moment you identify with the sense of “I” that it has its own concrete entity, that is neither body nor mind, but something that appears much more strongly.

When you think, “I really blew it!” you are not thinking my body really blew it, or my mind really blew it. You are thinking, “I really made a mess!” That “I” is so concrete, isn’t it? “I am a real loser, with a capital “L.”

Or remember a time when you did something wonderful or something really nice happened to you….

So, remember a time like that.

……something really nice happened to you, and you took great pride in it. This “I” that is so valued, so cherished, so liked, and is the object of such self-importance was so concretely and vivid clear. At such times our sense of “I” is particularly obvious.

Think of that “I” as it appears when you did something terrific and you got praised and you feel really good about it. Okay, got that feeling of “I”? Where is it? What is it? What are you going to draw a circle around and say, “That’s me!” Do you see what I mean when I say that it starts to hide? It appears so vividly, “I did this wonderful thing!” But when you ask, “What is this “I,” what are you going to hold? What is it? It seems it’s like it’s here and it’s concrete, but you can’t really put a circle around and say, “I found it,” can you?

It’s very weird, very weird. “I’m here. I did something wonderful,” but where is that sense of “I”? “It’s here.” Well where? Where is here?” “Here!” Where? “Right here!” “But that’s empty space, that’s just air. Where is it? What is it?” “Oh, it’s inside the middle of my chest. I’m there. Or maybe it’s at the back of my mouth, screaming “I.” Or maybe is inside my brain.” If you mentally dissect, if you unzip here, do you find “I”? “No, I just find ribs, lungs, heart, all sorts of goo. I don’t find “I”! In the back my throat screaming “I,” it’s not there either. In my brain?” If you mentally open up your brain, you find all these different lobes. Are any of them you? “Not, that, but I’m here, I’m sure I’m here. It feels like it.” We see how contradictory our mind is when we start to analyze; what we feel and what comes out of our analyses do not match at all.

Once you catch hold of such a blatant manifestation, you can cause this strong sense of “I” to appear to your mind, and without letting the way it seems diminished in strength, you can examine it, as if from a corner, whether it exist in a solid way it appears.

This is the trick. You have to keep that feeling of a very strong “me” very vivid, and just with one tiny corner of your mind check to see if it exists the way it appears. But as soon as we start checking if it exists the way it appears, we can’t find it!

In the seventeenth century, the Fifth Dalai Lama spoke about this with great clarity:

Sometimes the “I” will seem to exist in the context of the body. Sometimes it seems to exist in the context of the mind,”…

“Oh, I’m going to be reborn in another life. It’s my mind that carries the karma.” Or somebody says, “I’m so intelligent and creative. That’s my mind. I am my mind.”

Sometimes it will seem to exist in the context of feelings, discriminations or other factors.

“I am my happiness,” or “I am anger!” It seems to hide between in all those things, but as soon as we turn the spotlight on those things as if indeed the “I” is there, then it hides again somewhere else. It vanishes.

At the end of noticing a variety of modes of appearance, you will come to identify an “I” that exists in its own right, that exists inherently, that from the start is self-established, existing undifferentiatedly with mind and body, which are also mixed like milk and water.

We keep looking to try to find this “I,” but it keeps hiding. Sometimes it’s our body, sometimes it’s our mind, and sometimes it just evaporates into space. But eventually we come to see that the whole thought of “I” is something that exists in its own right, as if it sat itself up independent of everything else, existing inherently from the start as if it was self-established. In fact, there wasn’t even a start. “I’ve always been here, self-established. It’s not that I exist because there are causes for me. I just exist because I am me!” Existing undifferentiated, undifferentiatedly with mind and body—this independent self that seems to set us up also appears to be mixed in with the mind and body. That’s really contradictory, isn’t it? It sets itself up, but it’s also mixed in. It’s independent but it’s mixed in.

…with the mind and body which also seem mixed like mind and water,…

mind and body just kind of merge somehow.

This is the first step, ascertainment of the object to being negated in the view of selflessness. You should work at it until deep experience arises.

The remaining three steps, discussed in the following three chapters, are aimed at understanding that this sort of “I,” which we believe in so much, and which drives so much of our behavior, actually is a figment of the imagination.

This “I” that we defend, that we go berzerky over if somebody criticizes and doesn’t respect, is a figment of our imagination. Does it feel that way? No. See what I mean? The “I” that’s the “I” to be negated is the thing that “If this didn’t exist, I don’t know what does exist. I am sure that this exists. Yes. This is me!” This solid “I” does not exist at all. He didn’t say the solid “I,”—just half of it doesn’t exist. He said it doesn’t exist at all. Finish, kaput, nothing.

For the subsequent steps to work, it is crucial to identify and stay with this strong sense of a self-instituting “I.”

Then His Holiness gives a series of meditative reflections which I will read. In your next meditation, you can read these and you can do a little reflection on it.

Meditative Reflection

1. Imagine that someone else criticizes you for something you actually have not done, pointing the finger at you and saying, “You ruined such-and-such!”

2. Watch your reaction. How does the “I” appear to your mind?

3. In what way are you apprehending it?

4. Notice how that “I” seems to stand by itself, self-instituting, established by way of its own character.

That’s the first reflection. The second one is very similar, except for the example.

1. Remember a time when you were fed up with your mind, such as when you failed to remember something.

2. Review your feelings. How did the “I” appear to your mind at that time?

3. In what way were you apprehending it?

4. Notice how that “I” seems to stand by itself, self-instituting, established by way of its own character.

Also:

1. Remember a time when you were fed up with your body or some feature of your body such as your hair.

“I don’t have any hair! I don’t have any hair!” or, “I’m supposed to have straight blond hair and I have brown, curly hair. I don’t fit in!” Go back to being a teenager. Remember when you were a teenager and you were unsatisfied with your body, which was especially blatant when you were a teenager. Remember how you thought, “I need to look like that person in the magazine and I don’t!”

2. Look at your feelings. How did the “I” appear to your mind at that time?

3. In what way are you apprehending it?

4. Notice how that “I” seems to stand by itself, self-instituting, established by way of its own character.

Also:

Remember a time when you did something awful and you thought, “I really made a mess of things.”

Or even more awful, “I hope nobody ever finds out that I did this.” To say, “I made a mess of things,” we can admit sometimes, but when it’s so awful, then, “I hope nobody ever knows I did this.” Look at the feeling of “I” that comes then. That’s really strong, isn’t it? But it’s very interesting when we are feeling this strong “I” as in “I hope nobody ever finds out that I did this.” Is that “I” that you are holding to the “I” that did the action years ago, or the present “I”? Which “I” is it? You see when you start to analyze which one, “Maybe it was the “I” that did the action thinking, “I hope nobody ever finds out I did it. But the “I” that did the action doesn’t exist anymore. I don’t have to worry about that. I will worry about somebody finding out that I did it! But the present me didn’t do that. So which me am I afraid is going to be uncovered?” There is a very strong “I” there. It’s not the past one. It’s not the present one, but it’s right there, self-instituting, not dependent on anything. Like I said, the moment that you start to search for it, the moment you start to apply reasoning, the whole thing seems to fall apart. “It wasn’t me that did the action because that “me” doesn’t exist anymore. But the “me” who exists now didn’t do that action, so which “me” am I afraid is going to be revealed to the world as the ultimate sinner?” Very interesting, who that is.

1. Remember a time when you did something wonderful and you took great pride on it?

Or remember a time when somebody else did something wonderful and you stole the limelight and the praise. What kind of “I” appears then. “Oh, I am so smart. So-and-so did all the work and look at me. I am in the spotlight.” How does that “I” appear to you? How are you holding it? It appears to be out there, self-independent.

1. Remember a time when something wonderful happened to you and you took great pleasure in it.

For example, the Dalai Lama looked at you. Have you ever noticed when His Holiness walks into teachings, the Tibetans used to all have their heads down, but now all the Ingies and Tibetans look up, “C’mon, look at me, look at me. I’m here. I’m here being humble.” And then, he looks at you, and what is the feeling of “I” then? “Wow! I exist! The Dalai Lama looked at me. I can tell the world the he looked at me!” His Holiness walks in and out of teachings, and this is what’s going in 99% of the audience. He is trying to teach us what does not exist, and we are holding onto it like this.

There is some time for questions.

Audience: Why can’t the strong “I” be a dependent “I”?

VTC: Because the question he is asking is, “How are you apprehending that strong I?” Does it feel like to you that that “I” is dependent, that it exists just because of causes. It doesn’t feel like a dependent “I,” does it?

Audience: I am not sure that the strong sense of “I” necessarily contains in it the sense that is an unchanging, independent, something. I guess the question is why can’t either one have this overly high denotation of an “I” that is changeable?

VTC: We are not saying changeable or unchangeable. That’s not the definition of inherent existence. It is self-instituting, it is self-powered, existing from its own side. If something existed from its own side, it would have to be permanent, but being permanent is not the definition of inherent existence. His Holiness does say that if you are a Bodhisattva, you need very strong self-confidence. If you are a wimp, you can’t be a Bodhisattva. You need very strong self-confidence. But we usually think of self-confidence as this overblown “I” that is really there. Somehow there has got to be a way to have self-confidence, but realize that the “I” exists by being merely designated. As soon as we put any more solid stuff in there, then it’s independent of everything else.

Audience: I think it was said that things exist by being merely labeled through the power of thought. That power of thought or thought itself—is that inherently existent?

VTC: Oh, yes, now we are really getting something! Whose mind gave it the label? What is that thought that gave it the label? God? There must be some self-instituting something that gave it the label. No, that thought is just an energy blip through the mind, and other people seem to have similar kinds of thought. We all agreed to call something a thermos. That’s it. It’s not like, “My mind calls it a thermos. That mind is the real mind, the real me. That’s who I am, the one who called this a thermos.” That’s not going to work.

Audience: Yes, I was just going to say that it seems to be like a really fine balancing act to refute that very strong “I,” but still think or know that there is a conventional “I” that does produce karma, or that does….

VTC: This is the hardest thing about it all. This is the hardest thing, to find that fine line and negate exactly what doesn’t exist without negating more and without negating less. But we are extremist and we easily negate more and we easily negate less. It’s very difficult, they say.

Audience: I’ve been trying to take these things more looking at the side of the subject rather than the object. That’s what I was talking about, like here, the object of negation, and we’ve been learning how only certain kinds of minds can do to certain things. Ultimate analysis is the kind of mind that doesn’t seek conventionalities. It is the one that does something else. I am wondering a couple things, like when we are not looking for how the inherently existent person exists. We are looking for how the inherently existent person exists…

VTC: No, we are looking at how the conventionally existent person exists. The inherently existent person does not exist at all.

Audience: Ok, so…

VTC: We are researching how the conventionally existent person exists. But like I said, we have a hard time differentiating between the conventionally existent one and the inherently existent one.

Audience: But is it the mind of ultimate analysis that’s not finding the inherently existent person and not finding the conventional person and the aggregates?

VTC: If the self were inherently existent, it should be findable. The ultimate analysis does not find a findable “I.”

Audience: When we examine for the conventional person, we also don’t find in the aggregates that…

VTC: We are not searching for the conventional person. We are examining how the conventional person exists.

Audience: But we did say that within the aggregates, we don’t find the conventional existent person either.

VTC: No, because then it would be inherently existence.

Audience: Right, so what mind is doing that?

VTC: That’s ultimate analysis.

Audience: Okay.

VTC: But, but we say, “Oh I’m looking for the conventionally existent person,” but actually we are clinging on to an inherently existent person.

Audience: Right, okay! My last question is about the text, page 130, you said, “When you think “me,” do you exist through the power of thought? No. And then the text says “This mode of apprehension is your target.” Is the mode of apprehension there, is that the mind that’s doing that, or it seems like to me is more the mind that is grasping this…

VTC: Well, it’s both things. It’s the ignorant mind that’s grasping at inherently existent object. The object that you think is existing, even if that object is yourself, an inherently existent you, that’s the object of negation. You are trying to identify the object that ignorance holds. Ignorance is the mind, and so what is ignorance grasping at? What is it apprehending?

Audience: So when they are talking about the mode of apprehension, it seems to me a lot of times that in practice, you have to look at how the mind is grasping it.

VTC: Right, so here, how was the mind grasping it? As something real.

Audience: Right, it’s starting to sound like water poured into water.

VTC: No. How is the mind grasping it? There is a real “me,” independent of anything else.

Audience: Okay, thank you!

Audience: Yes, I was going to come back to the conventional thing. Is there a thermos there?

VTC: Yes

Audience: What mind knows there is a thermos there?

VTC: A conventional valid cognizer.

Audience: Okay, but you said there was no thermos there that we were looking for the thermos conventionally.

VTC: If, because I was saying, if we can, looking with a conventionally cognizer for a thermos there is a thermos, but if we are looking for an inherently existent thermos in this— because we are saying “I am looking for a conventionally existent thermos” but we are really holding onto an inherently existent one, we’re not going to find a thermos in this. It’s that same thing—Lama Zopa does this a lot—there is no thermos in this object, but there is a thermos on the table. There is no thermos on this object, but there is a thermos on the table.

Audience: And then that’s going ultimate analysis, just…

VTC: Right, there is no thermos in this object—you are looking with ultimate analysis. It’s weird. You are holding this thing and the same time the whole thing is disintegrating. It is like, “Wait, there is no thermos here,” but there is a thermos on the table. Is there a conventionally existent, findable, conventionally existent thermos in here?

Audience: No.

VTC: No. That’s what I was saying. There is no real conventionally existent thermos. That’s what we do. We say, “Oh yes, yes, yes, there is no inherently existent one, but there is a real conventional existent one”

Audience: Merely designated.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: But we can’t grock this.

VTC: No, we can’t grock merely designated, because if this is merely designated, what is it that’s in my hand?

Audience: Designation.

VTC: There is not just mere designation in my hand. I’m feeling weight, I’m seeing color, it’s hard, I can open it up and drink out of it. What do you mean this is mere designation?

Audience: That’s the part our perception. Thinking about it, it’s actually in our perception

VTC: Yes, it’s in both.

Audience: Yes, it’s in both, but for a long time I was thinking, “I can think my way out of this,” but my perception insists, like you just said, I see something white, I can feel something metallic, whatever. All of these things are saying, there is a real existing thing right here and it’s just like you are saying about the sunglasses. I never existed any other way in my memory. I don’t have a memory of not having those sunglasses on, so I can’t say oh just take them off.

VTC: Yes, because everything you look at, saying, “Oh, this is just the trees.” No, you are putting the sunglasses on.

Audience: I don’t have an experience of something. I have nothing to compare it to.

VTC: Right, and nothing to compare with no experience and, it’s a total opposite from what we always believed. It’s like we are little kids who are 100 percent sure the bogeyman exists. For sure the bogeyman exists. His Holiness is telling us, “There is no bogeyman. What are you talking about?” There is a bogeyman. Remember when you were a kid? Did you have any experience with the bogeyman?

Audience: So what is that continuum that carries forward?

VTC: The continuum…

Audience: In our mind that carries into a separate rebirth…

VTC: There is the mindstream, but ultimately it’s just the mere “I,” the merely labeled “I.” That’s the final thing that carries the karma, but that’s not something you can identify and find. The mindstream is the temporary basis.

Audience: That’s true, you can’t identify it, you can’t find it.

VTC: You can’t pinpoint it. You can talk about it, because all these conventional things exist when you talk about them. But when you try to pinpoint what they are, we can’t do it.

Audience: I’m checking out my experience…

VTC: Yes, the mere “I,” the mere “I” exist right now, we are experiencing the mere “I” right now. That’s the only “I” that exist, the mere “I,” but we can’t see it separate from all the junk we are putting on top of it. So, when we say the mere “I” carries the karma, it’s hard for us to just imagine what is this mere “I.” It’s got to be some thing.

Audience: Because the karma is something.

VTC: Yes, right. Because the karma is truly existent, so the “I” that carries the karma has to be truly existent.

Audience: How is my past I experienced my past versus Venerable Semkye’s past? My only answer is I that when I think of my past, I remember my past inner experience and I don’t remember Venerable Semkye’s inner experience. But that’s very, very flimsy. There is like nothing there, so when I think of the karma carrying forth, all I can think of is some being, some Buddha in the future is going to think of the past and have a memory of that inner experience and that’s it. There isn’t any solid thing that’s going to be there. It’s just that, and the memory is just what? A memory, right? It is not real, is not, you know, it’s not existent, self-existent.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: When Lama Tsongkhapa talks about the mind that’s not grasping at inherently existent, there is one that is more neutral. Can that one see the mere “I”?

VTC: Not separate from the inherently existent one.

Audience: Just the appearance still there, but you are not grasping it. So when we try to experience that kind of mind in our day, that’s when we are calm so??[Inaudible here 1:29:52] big “I” that’s the closest you can get from some kind of realization…

VTC: Right, the inherently existent “I” is still appearing to the mind, but we are not grasping at that time.

Audience: Can we say that the inherently existing “I,” inherently is not existent? Is it any such thing as non-existence?

VTC: No, inherent existence in any form does not exist.

Audience: Inherently non-existence.

VTC: No that doesn’t exist. This is going to require some thinking.

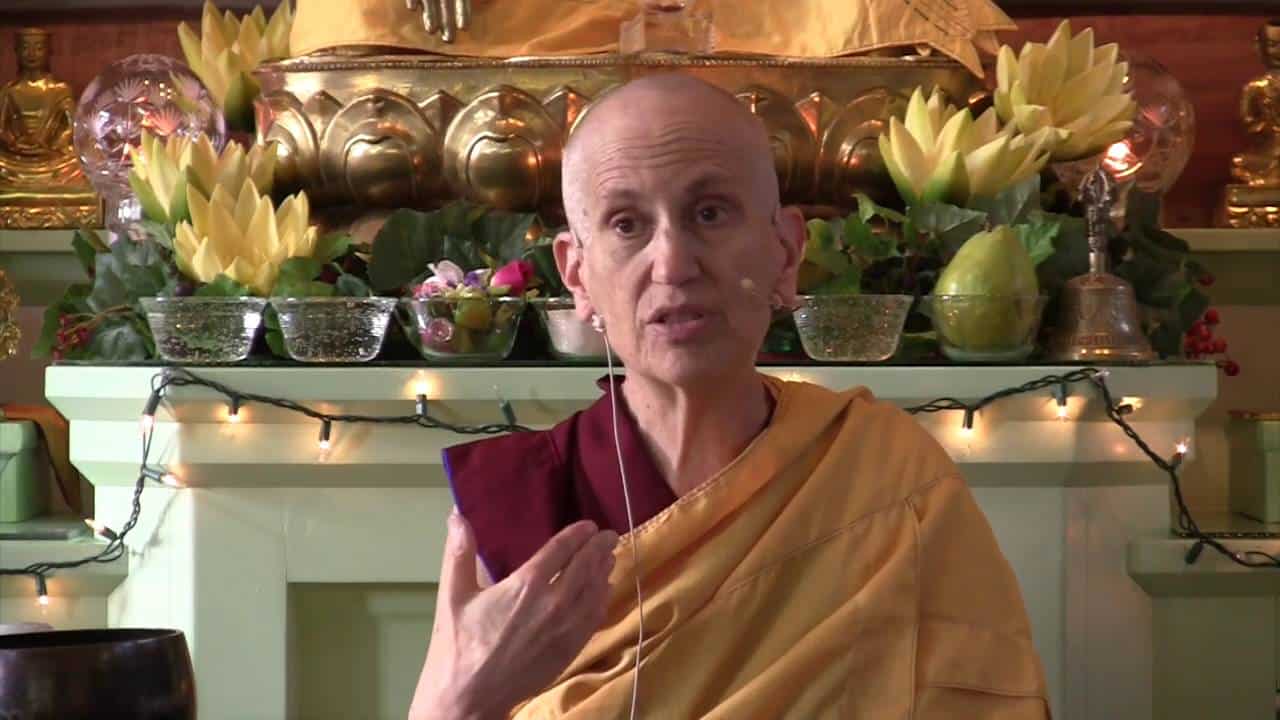

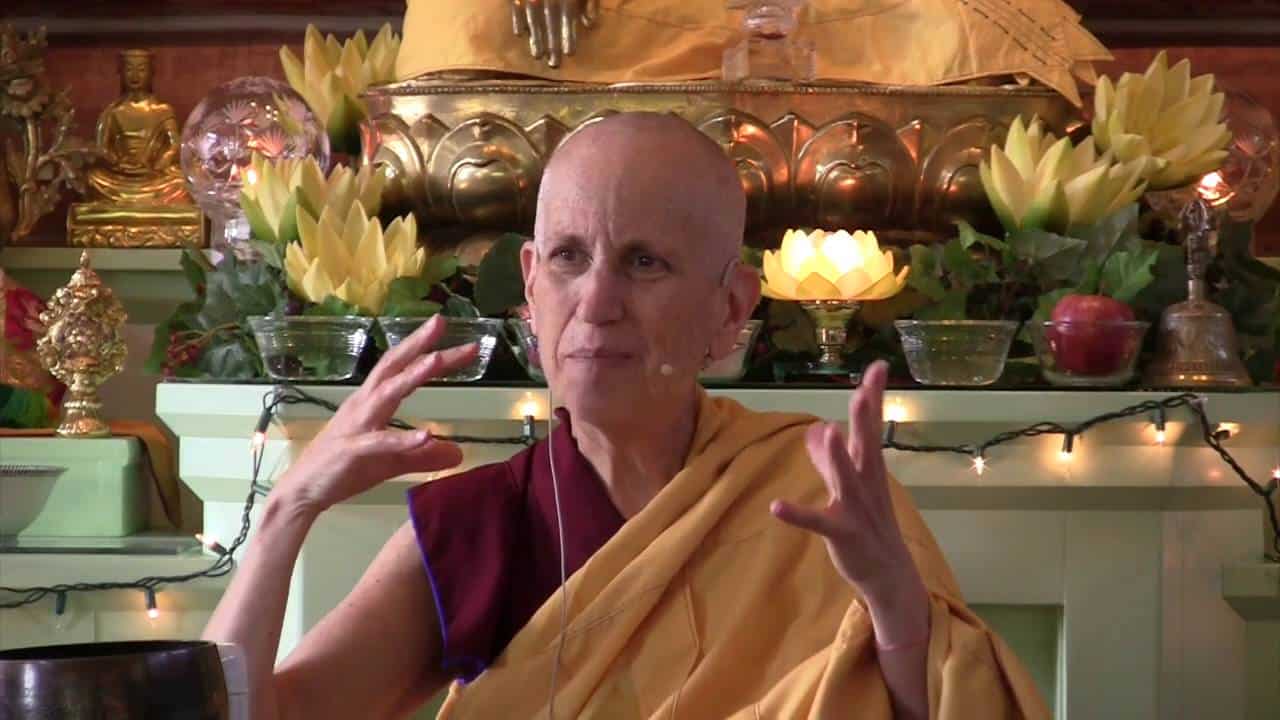

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.