Bodhisattva ethical restraints: Auxiliary vows 39-41

Part of a series of talks on the bodhisattva ethical restraints given at Sravasti Abbey in 2012.

- Auxiliary vows 35-46 are to eliminate obstacles to the morality of benefiting others. Abandon:

- 39. Not benefiting in return those who have benefited you.

- 40. Not relieving the sorrow of others.

- 41. Not giving material possessions to those in need.

Let’s cultivate our motivation and get in touch with the stillness in our own heart when the conceptual mind stops chattering away—that stillness that is there quite naturally without the clutter of so many distracting thoughts and emotions. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to connect with that stillness again and again and transform it into a wisdom mind that directly, non-conceptually, knows the nature of reality? And then wouldn’t it be great to be able to act out of that stillness, out of that wisdom, with a mind that’s totally uncluttered, knowing exactly what needs to be done to be of the greatest benefit to any sentient being at any particular time. We have the potential to actualize that state; let’s generate the motivation to do so and to listen to the teachings on the bodhisattva precepts, so that we can practice the path to that fully awakened state.

I believe that we left off with thirty-nine, we finished thirty-eight. Thirty-eight was “Not explaining what is proper conduct to those who are reckless.” Or another way of putting it, “Not showing those who are careless what is suitable.” So, this means really helping people who are going off in a wrong direction. Now we’re on the section called “Misdeeds related to specific objects to be helped.” There’s “Not helping others,” and there’s six points under “Not helping others.”

39. Not Repaying the Kindness Shown to You

The first point is “Behaving very badly in relationship to those who have been helpful to us.” This is precept thirty-nine, “Not repaying the kindness shown to you” or “Not benefiting in return those who have benefited oneself.” So, it’s not repaying the kindness of the people who specifically have been kind to us in this life.

This misdeed consists of disregarding people’s kindness towards us, showing no gratitude and not doing anything for them in return.

It sounds like the selfish teenager, doesn’t it? But sometimes that’s who we are.

When people have helped us by contributing towards our welfare in some way, ideally we should do something for them in return that is even kinder than what they have done for us. It not, we should do something equally helpful. Or failing that, at least make a small gesture. If we do not reciprocate out of anger or animosity, it is a misdeed associated with afflictions. Out of laziness, it is a misdeed dissociated from afflictions.

What are some examples of this, of people who have been kind to us? If we look at our present situation here, we have the whole lineage of teachers who have been kind to us—the Buddha who has been kind to us, our own spiritual teachers who have been kind to us. Then we have all the benefactors who have helped us so that the Abbey exists; we have all the volunteers who come up and help us with different events, and people who make offerings, material offerings, people who offer service, people who give us advice about one thing or another—all these kinds of people who directly benefit us in this life. We have our parents who gave us this body, sometimes our parents benefit us in a Dharma sense, sometimes they become a hindrance, it depends. In any case, they certainly benefited us by bringing us up, giving us this body and making sure we got an education. And all of our teachers, from kindergarten up through who knows what, all of our Dharma friends, all the different people who have actively benefited us. So, this means really having the mind to repay their kindness not taking what people have given us for granted.

When it comes to the whole tradition and to our spiritual teacher, it’s not just saying, “Oh well, they’re always there and I’ll come around when I feel like it. Anyway, they have enough. I don’t need to do anything. They’re the ones who are supposed to be kind and compassionate to me, not me repaying their kindness.” It’s that kind of attitude.

Similar to the benefactors and supporters and volunteers, it’s important that we really see that we couldn’t sit here and have this class today if it weren’t for all these people who were supporting the Abbey—people who believe in what we’re doing and who supported through the material that they’re earned by putting their time into their jobs and people who support us by their volunteer work. Really feel the sense of connection with those people and a sense of gratitude and try to repay their kindness. Then the question comes: how do we repay their kindness? First of all, it’s to have that feeling of gratitude—that in itself overcomes complacency, arrogance and all those kinds of nasty minds that expect people to be our servants.

It’s generating that mind and making dedications for those people, including them in our prayers and our dedications, including them in our motivations. Then when they come here, directly benefiting them and helping them, reaching out to them, being friendly and cordial, leading meditation groups, leading discussion groups, leading Q&A sessions, really sharing the Dharma with them. Also when they need, if somebody is sick, doing what we can to help them as well. So, it’s really feeling that connection with all the people on whom we depend to have this present opportunity. That’s a lot of people when you really think about it and many of them we don’t know. Venerable Chonyi and I have been speaking a lot about this the last few days, since we came back from Singapore. Just seeing people’s attitude, their wish to help and their wish to give, you really feel like, “Okay, I need to practice and develop myself to give back to them.” And in the meantime, it’s important to really dedicate for them.

An exception is made in relation to the basis when we want to return the kindness we have been shown, try to do so but fail because we are incapable.

That’s an exception, we try and repay the kindness, but we fall down and go “boom” in the process. That’s an exception. The important point here is that we tried.

An exception is made out of necessity, when it is better for the person involved not to be rewarded. In some cases in the long run it is more useful not to reciprocate people’s kindness even if it hurts or disappoints them slightly at first, for they have come to expect something in return for their services.

So, if it’s a case of somebody who is being kind to us but then expecting us to do things their way, or somebody who is expecting us to endorse them no matter what they do or to support them no matter what they do, or somebody who is trying to possess us as their private monastic or something like this, if we don’t reciprocate it could be for their benefit, in the sense of hopefully waking them up and helping them to see that their motivation had gotten off-base somewhat. Of course it risks the danger of making them quite angry, too, so you have to have a good relationship or some way of making sure that they understand and get the point.

This can be important. I’ve seen certain situations where people have been very generous to some monastics or to a monastery, and then they hope to control it—control the policy or whatever. You don’t want to go along with that because the policy of a monastery should be made by the monastics, not by lay donors. It doesn’t mean you’re hostile or anything, but you just don’t go along when somebody is wanting to have too much influence. That’s never happened to us, but I’ve seen it happen in other groups.

I have some Dharma friends whose families are so generous with them, support them so well, that it actually in some ways becomes burdensome for them because when there’s a family vacation their parents pressure them to go, and they have to miss teachings in order to do that. Because they feel so indebted to their family or because their family says, “Look, we’re supporting you all the rest of the year so you can do Dharma, the least you can do is go on a cruise with us when we ask you.” Maybe going on a cruise isn’t the best thing for your mind. These kinds of situations come up, so you have to really think of what’s beneficial and not beneficial in terms of repaying their kindness.

There’s an exception regarding the object—the people who have been helpful who sometimes have no desire for our kindness. If they do not want us to express our gratitude and repay their kindness, we should not impose it on them.

One person that we went to lunch with last week was telling us that she had made a contribution to one of the Buddhist centers in Singapore and one day they sent her one of these big things with flowers and fruits, these huge baskets with stuff. She called them and said, “What’s this?” and they said, “Oh, we want to show our appreciation for you.” And she said, “Why are you spending the money of the Dharma center to buy me flowers and fruits? I don’t want this, the money should be used for the purpose of the Dharma.” She had a very good mind; she wasn’t expecting flattery and so forth. It’s interesting because we went out to lunch with her and we had brought along a gift. I went to give her the gift, she said, “No, don’t give it to me,” and I said, “Don’t worry, I didn’t spend any of the Dharma center’s money on this.” When I said that she accepted it.

But it’s really important to appreciate the people and to thank them—not thank them in a sense of flattering them or anything like that, but just out of genuine gratitude and helping them to rejoice at their own virtue. I’m teaching this in terms of a monastic. For a lay person, it’s going to be a different relationship in how you repay the kindness of others. Because maybe with them, you help them move from one house to the other on a Saturday afternoon, you help them pack up their things in one apartment and move to another apartment. There may be different ways to reciprocate the kindness that others have shown you.

40. Not Easing Others’ Distress

The second of the six under this category of Not helping others, “is behaving very badly in relationship to those who are unhappy.” This is precept forty, which is “Not easing others’ distress” or “Not relieving the sorrow of others.” He says:

When people are suffering mentally, are very worried about something for example, and out of animosity towards them we do nothing to relieve their distress, it is a misdeed associated with afflictions. If we fail to help out of laziness or sloth, it is a misdeed dissociated from afflictions.

Before I go into this one any deeper and this is not easy thinking of others’ distress, I was thinking about our NVC session last week when one of the examples was somebody who says, “I was up all last night worrying about the presentation, so I drank too much coffee this morning. Now I have this horrible headache, and why in the world does this always happen to me?” During our whole discussion of that, I realized something very important about myself, which is I don’t like people who whine. I don’t like when people whine. That was a whining thing: “Why does it always happen to me—ooohhh.” If that person had said, “I worried all night and didn’t sleep, so I drank too much coffee and that was a really silly thing to do because now I have a big headache,” I would have said, “What can I do to help you?” Because that person is being honest and direct, and they’re owning their responsibility in it.

But when people whine—ooohh!—it’s so hard for me to help them when they’re in distress, when they whine, because when I see that people have created a situation themselves but won’t own their own responsibility, I don’t like that. Also, I think another reason I have difficulty when people whine is because I’ve found that sometimes I try and give them some advice to help and the answer is always, “Yes, but.” That’s how whiners usually respond—“Yes, but”—which also drives me crazy because I think, “Why are you asking me if you don’t really want to listen?” I’m just telling you what goes on in my mind. Whereas with somebody who just says, “I made a mistake,” I’m very willing to help.

Another thing about whiners is I run into a number of whiners who try to manipulate you by whining and getting you to feel sorry for them. I really do not like when people try and manipulate me. That I really do not like. It’s amazing to listen to our NVC discussion, when some of you were saying, “Oh, you must feel tired or exhausted because you need a better situation, how can I help?” I don’t want to say, “How can I help?” to somebody who whines because then they’re going to try and get me to rescue them, manipulate me into rescuing them, and I refuse to do that because it doesn’t benefit them, and it doesn’t benefit me. But I never realized until that NVC discussion.

Audience: That’s so funny because when I first moved here, like within the first month, it was said to me three things to do when you’re here. One was “Don’t complain about anything.”

Audience: Can you give an example of a sentence when you say manipulate, without coming out directly and saying, “I need some support,” to get you to rescue them.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Right. Like this lady in the made-up story: “How come this always happens to me?” And then you say, “How can I help you?” and she says, “Can you re-arrange the schedule so that somebody else gives their presentation today and I give my presentation tomorrow?”

Audience: And if you say, “No” and you go to these other things that you might help with.

VTC: But then she just continues on with: “But I have such a bad headache and I just can’t give the thing today, can you give your presentation instead?” or “Can you give my presentation, because I just can’t do it.” They try all these kinds of things. You may keep saying, “No,” but it’s not eliminating their distress, is it? It’s saying, “No, I can’t do that.” Because what they’re asking is not very helpful, but it’s certainly not eliminating their distress. Basically, because I think sometimes when people are in that whining mood, unless you do exactly what they want, their distress does not get eliminated. They’re not going to satisfy for anything less than you’re buying into their story of “Poor me,” which I do not like to buy into.

What do you people think, do you have that problem too? With whiners?

Audience: I’m a whiner so I don’t like them and I am one, but I think for me the whining happens when—it was a little bit of the teaching last night about not balancing and taking care, keeping mindful of the state of my mind, the state of my body, the state of my emotions to be able to ask from that place of needing support rather than not wanting to own to the fact that I’ve not paid attention very well, that’s where my mind comes from. I just push myself in the corner and then I want somebody else to take care of the corner.

VTC: So, the whining is coming from not wanting to own that in this case, you weren’t being mindful of the state of your body and mind and you got yourself all run down, so not wanting to own that you had something to do with it and wanting somebody to come in and rescue you.

Audience: But like you said, if it’s not done exactly the way that I wanted it doesn’t serve, and I’ll just continue to whine to somebody else and then somebody else until I get what I want.

VTC: Yes, that what’s what we do when we whine, isn’t it?

Audience: Two thoughts. One is that whining is evaluating a whole set of behaviors. They can be really bad, “Poor me,” right out there or just somebody drawing something out. Like in that example, I felt like that line, “Why does this happen to me?” wasn’t even the most important part of the whole thing. I make a try with someone doing that; one, two, or three things, then they “yes, but, yes, but” then I stop. But I make that first try because my experience is some people shift and they’re not only “It has to be my way.” So, it’s that word “whining” that’s evaluative.

VTC: Oh, it’s definitely an evaluative word, definitely. Whining is evaluative, but you say that you’ll reach out to them a couple of times and if they keep saying, “yes, but” then you just give up.

Audience: Well, I just do something else, like go a different way.

VTC: But you do see that sometimes they shift.

Audience: Yes, and sometimes not.

VTC: How about other people? You have a hard time removing the distress of whiners? I’m using it, it’s an evaluative word, but…

Audience: The part I resonate with is that the person isn’t taking responsibility. I also whine, in those moments I’m not taking responsibility, so it’s kind of a powerless situation in a way. The person who is in the situation isn’t using their power to do anything and the other person actually can’t change another person, so it’s a lose-lose if that’s a strong component of what’s going on here.

VTC: Yes, somebody’s feeling powerless, and you can’t make them get in touch with their power to change the situation—once in a while maybe.

Audience: I think sometimes if you point these things out—actually, this happened during this retreat. When I had this discussion with this man, I said to him twice that the way that he said something, wasn’t owning responsibility for it. I pointed that out to him twice and he seemed receptive. I’m not sure if it went in, but there are some ways where sometimes people are receptive and sometimes they aren’t. I guess if you can find a way to just be direct and still be caring, that would be nice.

VTC: A way to be direct and caring at the same time—maybe you’re saying to that person, “You’re not accepting responsibility.” It may not go in immediately, but maybe they’ll think about it later. When you were saying that it just came to my mind that sometimes with whiners I find the best thing to do is to have them sit in on a Dharma teaching and then you talk about how the self-centered thought works to the whole group. Because they don’t want to hear anything directed specifically towards them; usually they don’t want particular advice towards them. But if they’re in a group, you start talking about how the self-centered mind works, how it causes pain and distress and to see it as an enemy, sometimes they will see it in that kind of situation and apply it to what’s going on their lives.

Audience: One time some years ago, I think you said something to me once about the way I was interacting was like trying to cause some guilt. This is what comes out of that thing, when a person does not own their own behavior, you guilt-trip other people. I think we can point these things out to others and sometimes, at least in our situation, direct us. Sometimes I think we need it when we’re not getting it, but other times it’s quite helpful to hear it in a less direct way.

VTC: Right. So, it depends on your relationship. If you’re close to somebody and you know that they are really trying to work on themselves, pointing it out can be very helpful to them. But when it’s somebody who doesn’t have that same kind of self-awareness or willingness to work, sometimes better just in a group situation and hope they pick it up.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: It was funny—that was just like this light bulb going on. Because I’ve realized sometimes when I travel and teach, people come up to me afterwards. There might be a whole line of people who want to just come and make offering and that one person wants to stop, tell me their story and wants me to cure their problem. I find those situations very difficult because I try and say, “Would you mind waiting until the end and talking to me?” But even then, I’m so exhausted after giving a talk and talking to all these people that I’m not at top performance at that time. I’ve always found that a challenging situation when I’m traveling and there are large groups after a talk. Anyway that was just sharing something I observed about myself. So, if you’re ever whining and you wonder why I don’t sympathize, this is why, okay?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: I didn’t know it so clearly. I knew I didn’t like those situations, but I hadn’t hooked up what’s the common denominator in those situations. The common denominator is somebody who is unwilling to take responsibility for their own situation and is somehow wanting me to fix it within two or three minutes.

Audience: I think that’s where we have to find a way to show the person that…

VTC: Yes, without offending them.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: I would offer encouragement in that example. I would say, “Yes, you might have a headache but my experience is once I start talking I forget about that and I get involved in what I’m saying. I feel connected to the people and I find that, actually, I have the energy within me to do it without letting something like that distract me.” So, I would try and encourage them, but in NVC we weren’t allowed to do that.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: No, we were supposed to respond empathetically and not give advice.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, it’s encouragement, but it’s advice. And the idea was to respond empathetically which was, “How can I help you?” but for me that would be actually dishonest because…

Audience: I didn’t think “How can I help you?” was empathetic.

VTC: You didn’t think that was empathetic?

Audience: When people said, “How can I help you?” This to me is not empathy.

VTC: Oh, so what’s the empathy then?

Audience: Well, it’s the feeling in me. I think it’s just connecting. To me, it seemed like it was connecting with the person in a way that cared, but it didn’t mean “How can I help you?”

VTC: Um-hum. But what would be a way to express that verbally without saying, “How can I help you?”

Audience: Kind of reflect back their feelings to start with, “You’re feeling tired and you’ve got a headache” just reflecting back what they’re saying so they can hear it. And then saying, “What do you think you need? Do you need some kind of support to go ahead with the presentation?” Then you might get the “yes but.”

VTC: “I can’t give the presentation!”

Audience: You might get that but you try first, because one thing I just noticed is you said a person who is unwilling to be open. That’s why I try because I’m not sure they’re willing or not. Maybe you’re talking about the situation where you know the person pretty well, we’ve been through this, but especially with someone new to me whether they are unwilling, I’ll know it after a couple of sentences.

VTC: Right, yes. That’s true, and that’s why if I don’t know I usually try the advice and the encouragement in order to empower the other person, but I was talking about this in terms of people that I know, that I’ve been through the wringer with.

Audience: Yes, so different context.

VTC: Yes, but this is something I know I have to work on. I’m wrestling with that, how to do that in a skillful way. When I’m tired and I have needs because I’ve just given a two-hour Dharma talk and greeted a whole line of people, and it’s 10:30 at night, and I want to go to bed.

Audience: I think that for me, what I would do in that situation is I have to get rid of the evaluative thing on my side about them, and then number two, I have to find a way to let them know what I’m capable of in that moment.

VTC: So, get rid of the evaluative language and then you said let them know what you’re capable of, so just saying, “It’s really late and I’ve given a Dharma talk and I’m really sorry, I’m not going to be a very good listener right now.” That’s pretty honest.

Audience: Because when I have the evaluative language in my mind, I’m not going to be connected. That’s the first thing, because the whole judgmental or diagnosing or whatever it is, doesn’t lead to a connection. The other part is, I remember at work I came to a place where I realized I’m like a limited commodity, do you know what I mean? I only have so much capability in some moments, some days and some weeks and I have to preserve it so I can use it. I realized that and that helped me to be more assertive about what I was capable of doing in a moment, in a way that was easier, it was actually easier.

VTC: Yes, that could be quite good. Be direct with the person about what I’m capable of. It’s just interesting though, within some cultures they expect you to always be capable.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, but sometimes there’s really that expectation, that you don’t get tired, you don’t get sick.

Audience: But to be able to say “I’m really sorry,” genuinely, “at this moment I can’t help you.”

VTC: “I can’t help you,” yes. That’s true, because that’s honest, to say, “I’m really sorry you’re suffering and I can’t help you right now.”

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: And you know what’s interesting? It’s that this all comes down to being truthful and saying what’s true and how difficult it is for us sometimes to say what’s true—when it comes to saying, “I’m exhausted and need some rest,” where it’s just telling the truth. It’s not pushing anybody away or anything like that. That’s true.

Audience: I’m trying to think the labeling is important, because if we use these words, then I don’t think we’ll be as honest with ourselves. Because we’re putting it on them, they’re the whiners and the problem is they have their situation, we have our situation and they aren’t matching.

VTC: Right. The two situations aren’t matching. And calling them the whiner puts the blame on them.

Audience: Even if they’re doing that.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: Last night when you were talking “I need my space,” who needs the space?

VTC: Yes. When we were talking about space last night. I see that there’s knowing the difference between what you’re capable of doing at a particular moment and just being honest about it without any emotion versus “I need my space and you’re infringing upon it,” completely shoving the other person away. That’s the difference between just saying, “This is what I’m capable of,” and the other one which is saying, “You’re doing this, this, this and this and making me feel this, I need my space so get away.” One is just a clear statement and the other has so much negative emotion behind it. I see a big difference between those two.

Audience: One is compassion for self—“This is what I’m capable of”—and probably compassion for the other because you’re not trying to do things you can’t do. And the other one, it seems it’s not compassion; it’s quite different.

VTC: Yes, anger.

Audience: But the way I understood it last night, when you were talking that it’s about being able to stretch ourselves, I think my limit is there, my space, but I can stretch it, that’s how I was understanding it last night.

VTC: In some senses there is that situation where we have our cave and we decorate it.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: When we’re stuck in that we’re taking refuge in our own confusion. At that point our own narrow way of thinking about ourselves just gets us totally stuck. So, at that point, when we say, “I need space,” that isn’t the pushing-away, putting-a-wall-down-between-me-and-somebody-else statement. It’s the thing of, “I’m taking responsibility, looking inside and I need to make my own mind more spacious because right now my mind is too concrete, too narrow.” There’s a difference between saying, “I need space,” and “I need space!” There’s a difference between the two, isn’t there? It’s the same words, but that’s the difference I’m getting at. The first one is: “I need space, in my own mind. I need to create more space.” And the second one is: “This world is driving me crazy and impinging upon me, and I need to push it away and have space.”

Audience: There’s something in this, Venerable. I’m not sure I can articulate it, but I know that when I’m in that kind of situation the part of me that feels like I should fulfill their expectations is what gets me defensive, leading to labeling “whiner” and blaming them. That’s me trying to buying into some image I have of myself or something I want them to think about me.

VTC: Right. And in this situation I feel it’s very much the social situation that I’m put into because of other people’s expectations, so it’s very hard for me. I adopt that expectation of myself, too, yes? Also because there was something in my early training that was not necessarily so healthy but was in the background a lot which is, “If you only had more compassion, you would…” I would say that to myself a lot. And sometimes by pushing myself it worked. I must say not all the times I pushed myself have been bad. Some of them have been quite good because I’ve really been able to break through things and do things I didn’t think I could do. But it’s just when I do it too much like in this situation and think that I should be able to remedy their problem.

Audience: Or at least try. Or at least look like I’m trying.

VTC: Right. All I want to do is go to sleep.

Audience: With NVC, it seems statements like “I need my space” are a signal for unmet needs.

VTC: For what? Unmet needs, yes.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes. What is that space? What do you really need? Could you be more specific? But it’s difficult when somebody says, “I need space!” to go to them with NVC language. Because they’ve already put us up this wall and put you like that. It really takes special courage or compassion to approach somebody in that situation because what they basically said is, “Don’t come near.” Sometimes they really mean that, and sometimes it’s actually a cry for “Please come talk to me” but you don’t know which one it is.

Audience: That’s why I think the tapes with Marshall are so outstanding because he always gives a try. Some of the situations he described, I would never wade in and say, “How are you feeling?” but for him, it has worked because he brings that courage and that constant wanting to connect; somehow he’s just got that down. It’s quite a model. Like you say, it’s really hard.

VTC: Yes, to have that kind of courage to approach somebody who has just pushed away.

Audience: And who looks like they’ll blow up if you ask the other questions. It might be.

VTC: Yes, right.

“The anxiety in question here—[this is more of a commentary on this precept of ‘Not easing others’ distress,’—has two possible sources, the loss of loved ones and the loss of property.

I think the distress could probably have more sources than these two, but this is what the commentary is talking about.

The commentary describes various categories of loved ones from whom separation can be very painful. Somebody is in distress because they have been separated from parents and relatives, from a spouse or child, from servants and employees who are like old family retainers. They’re separated from kind and loving friends and companions, and they’re separated from helpful spiritual teachers who have contributed towards one’s spiritual development and with whom one shares the same values.

Those are situations of where people are in distress because they have been separated from those different categories of people.

In addition, separation from property can be painful. The commentary indicates that anxiety regarding property arises from either common or specific causes. Common causes of anxiety regarding property are thieves or authorities such as the government that may confiscate it. Others are fire and water which may damage or destroy it.

Those are common causes of anxiety regarding our property, losing our property.

Specific causes of concern about losing our property are our own mistakes or others’ errors. In the first case, it may be that one does not properly look after one’s property. One may choose a bad place to hide one’s cash or treasures so that someone else finds them or one may forget where one has hidden them. A more contemporary example would be to choose the wrong bank in which to open an account and losing one’s money when it goes bankrupt. One can also err in the way that one goes about making money by choosing the wrong company to invest in, for example. Losses caused by others may occur when someone else takes one’s shares of an inheritance or in another family situation, the parents may work hard to build up a certain capital only to see their children squander it in no time.

These are all situations in which the person we’re talking to may feel distress, and we should try and help them through their distress. It’s interesting. He doesn’t actually describe what easing others’ distress means or how to do it just what causes it. Isn’t that interesting? There’s no description about how to do it.

When people are distressed by the loss of a loved one or of their property and out of animosity we do nothing to alleviate it, thinking, for example, ‘it doesn’t concern me and they’re getting what they deserve anyway,’ it is a secondary misdeed associated with afflictions. When we are just too lazy or slothful to act, the misdeed is dissociated from afflictions.

The exceptions to this fault are the same as those for the thirty-fifth misdeed, Not going to help others when it is needed in the eight particular situations—[so the exceptions there are the same here]—if we don’t alleviate others’ distress because we’re ill, because we have another appointment, because we’re presently occupied in very positive and beneficial spiritual practices, because we’re not intelligent or lack the ability and skill to do it, when doing it would be harmful or contrary to the Dharma, when the people are quite capable of managing on their own or already have potential helpers whom they have yet to contact.

In the case of the whiners that I’m talking about, I’m continuing to label them, this is the one, because often I feel they are quite capable of managing on their own.

If for their spiritual development it’s better that you don’t alleviate their distress, if you don’t do it to avoid upsetting or irritating many people and giving them reason to criticize or reprove us, or if it’s to respect the monastic rules.

In those kinds of situations if you don’t ease others’ distress it’s not a transgression.

41. Not Giving Wealth to Those who Desire It

The third one, the sixth of “Not helping others,” is behaving badly towards the needy. So, this is precept forty-one, which is “Not giving wealth to those who desire it” or “Not giving material possessions to those in need.”

When someone wants food, drink or other goods and asks for them in a correct manner—

So, if they’re polite, timely, they’re not being rude and obnoxious.

—refusing to provide them out of anger or animosity is a misdeed associated with afflictions and refusing out of laziness, sloth or carelessness is a misdeed not associated with afflictions.

There are a number of exceptions for not giving wealth to those who desire it.

First, in relationship to the basis, or the subject, there is no misdeed when we do not have the things that are asked for.

That’s kind of obvious.

In relationship to the substance requested, there is no fault in declining to give someone something that would be harmful to the person in their present or future lives.

This is like somebody asks you for cigarettes or alcohol or pills that they don’t really need, weapons, poisons, these kinds of things.

Furthermore, we may legitimately refrain from giving out of necessity when providing what we are asked for would be injurious to the authorities, such as the government or to society at large.

What would be an example of that, not giving what somebody asks for because it would injure the authorities such as the government or society at large?

Audience: If somebody asked me for a gun.

VTC: Yes, if somebody asks you for a weapon.

Audience: If you work for the government and have some sort of confidential access to certain things that were important for the government security and they were asking for passwords.

VTC: So if you work for the government and somebody was asking you for confidential information.

Audience: Or somebody that you know, maybe a drug dealer who wanted a space to store things.

VTC: Okay, somebody who is a drug dealer, an arms dealer, wants to store their stuff in your house.

Audience: Or asks for your help in other ways.

VTC: Yes, maybe they need you to rent one of the storage spaces, a lot of drug dealers use those storage spaces. One guy wrote me and he was telling me his whole history of how he got arrested. He had put all of his drug paraphernalia in a storage locker.

The same is true when giving it would conflict with following monastic rules and when not giving favors the person’s progress.

If we would have to break our monastic precepts to give, we don’t give. Or if not giving would actually increase the person’s progress.

There could be a situation let’s say with a teenager, you’re a parent and your teenager asks you for money or your young adult child asks you for money and then you think, “Oh, if I give it to them, they’ll just always expect it to be here; if I don’t give it to them, they may think about getting some work or become more responsible themselves.” There could be that kind of thing happening. Parents have real difficulty saying no to their kids, they really do. Whatever their kids want, they want to give to their kids. But sometimes it could be actually better for the child not to.

Audience: We were teenagers who used to find certain adults who would go buy liquor for us. I had totally forgot that until you just said that. They would do it to be friendly. They felt, “This is friendly” when they were buying the beer for fifteen and sixteen year olds.

VTC: So adults who would go buy alcohol for underage kids, thinking that they’re being friendly, nice and kind to these kids.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, parents taking drugs with their kids and teaching their kids to take drugs. It happens, too.

These are very practical ones and there’s a lot to think about, isn’t there, when it comes to not giving material things when people ask? Sometimes somebody says, “Can I borrow a book?” And I’m too lazy to go get it for them. Maybe you can say, “Sure, here it is” and give them directions to go find it themselves. But there are lots of times when people do ask us, and we can help, but it’s just either we’re too lazy or out of resentment or animosity we don’t want to help them. That happens a lot, doesn’t it?

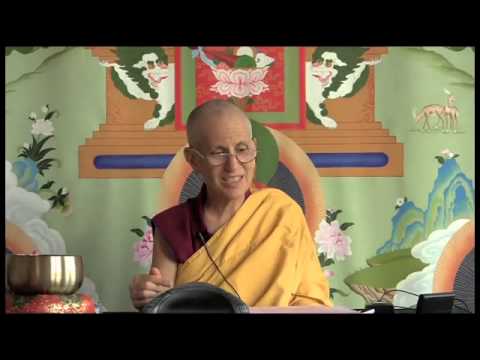

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.