Bodhisattva ethical restraints: Auxiliary vows 36-38

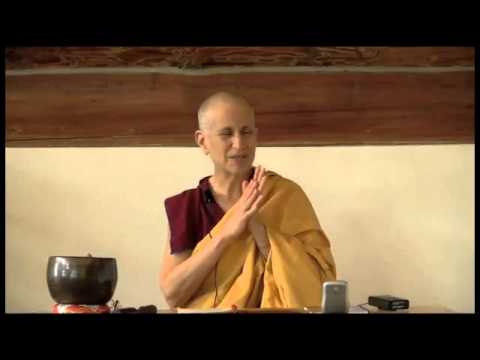

Part of a series of talks on the bodhisattva ethical restraints given at Sravasti Abbey in 2012.

- Auxiliary vows 35-46 are to eliminate obstacles to the morality of benefiting others. Abandon:

- 36. Avoiding taking care of the sick

- 37. Not alleviating the sufferings of others.

- 38. Not explaining what is proper conduct to those who are reckless.

Let’s generate our motivation. Realizing or trying to realize that there’s no findable self who is listening to the teachings, let’s listen to the teachings with an attitude of compassion for ourselves and all beings. Also knowing that all these beings are not findable when we search for them, and ourselves as the person having compassion for these unfindable sentient beings is also non-findable when searched for with analysis. So, even though we can’t isolate anything that is any of these objects, still they all arise and exist in dependence on each other, in dependence on their causes and conditions and on the mind that conceives and labels them.

It’s in this way that things are like a dream or like an illusion in that they appear one way but exist in another. Still, because sentient beings have feelings and want happiness and don’t want suffering, it’s important to do our best to bring that about. For that reason we’ll share the Dharma this afternoon.

Another way of understanding the precept

We had completed number thirty-six in this book. I was just noticing that in the book we got at His Holiness’ initiation the translation was “The Eight Groups of those in Need”, which is a little bit different, so I thought to go through it. It’s not that one’s right and one’s wrong, but it gives us more to think about in terms of helping sentient beings. They listed the eight groups; the precept is Not Going to Help those in Need. It’s specifically but not limited to persons needing help.

Making a decision about something positive corresponds with our first one here. Two was in travelling, so that actually skips the second one and goes to the third one. Then C, in learning a foreign language, that one is not on our list. It’s a funny one; I don’t understand how that got in there. Fourth is in carrying out some task that has no moral fault, like helping those who want to undertake a worthy enterprise. The next was in keeping watch over a house, temple, or their possessions—so protecting others’ possessions that we have. In stopping a fight or argument, that’s a little bit different, because what we have in this book is reconciling those who are at odds with each other, whereas this one seems more like they’re fighting or arguing at that moment and you intervene. The next one is in celebrating an occasion, so we have that one. And then the last one is in doing charity work which we don’t have. But we have instead the one on helping in festive occasions. It seems to me that helping somebody doing charity work would be more important than helping somebody in a festive occasion. So, I just thought to go through that because it gives us more situations to think of.

Of course the real thing to do is in our daily life when people ask us for help, look at our immediate response and see if there’s spite or anger or laziness, something that would cause a transgression of not wanting to do it. Or if when people ask for help we think, “Wow, this is so good, I can create some merit,” or “I can help somebody.”

37. Not Removing Others’ Suffering

Thirty-seven is “Not removing others’ suffering.” This one says:

Neglecting to serve the sick because of anger, spite, laziness, or indifference.

And this one says:

Avoiding taking care of the sick.

Not removing others’ suffering is much broader because it’s not limited to physical suffering. The explanation says the previous fault concerns not helping the sick in particular. I skipped one, let’s go back.

We’re in the section now that is “Not eliminating what harms others,” and this point has two sections. “Not eliminating suffering” and “Not eradicating its causes.” The first has two parts: “Failure to alleviate particular forms of suffering” and “Failing to alleviate suffering in general.”

36. Failing to Serve the Sick

[Thirty-six is] Failing to serve the sick. The misdeed consists of not helping sick people, whether we know them already or are meeting them for the first time. By nursing them, providing medicine, giving advice, encouragement and so on. When anger or animosity motivates our refusal, the misdeed is associated with afflictions. When we are too slothful or lazy to help, the misdeed is dissociated from afflictions.

The exceptions are similar to the previous. In terms of the subject—[us]—there is no misdeed when we do not help a sick person for the following reasons. First is we’re sick ourselves.

It’s clear that if you’re incapacitated, you can’t help somebody.

Second, we find someone else to help the sick person who, moreover, gets along with the patient very well.

So we find somebody else who can take care of them. But we have to make sure that the person we find is really willing to take care of the person and gets along with them, not that they’re just going to come in there and give them an aspirin and leave.

Three is we’re busy caring for another sick person. Four, we are not very intelligent or very good at looking after others. We have limited abilities to learn, reflect, and meditate and therefore, need to concentrate very hard on improving our understanding by study and meditation.

So, if we’re really slow in learning the Dharma or whatever, then we need to focus on our study and meditation. However, I think that—and this includes if we’re not very good at looking after others—if you’re not very good at doing it and you don’t know what to do, then you don’t want to intercede in that. But also you don’t want to use this thing of, “I’m kind of slow in my studies so I can’t help somebody” as an excuse. It’s not a very good excuse because if we’re slow we also need to create merit and helping somebody else is a way to create merit.

There are exceptions in terms of the object—[the people who are sick]. First, the patients are already receiving satisfactory assistance and have other protectors, so they aren’t in dire need of help. Second, it’s somebody who is capable of looking after themselves.

Again, it’s a situation of they don’t really need help that urgently.

Three, they have been ill for a long time and are well on the road to recovery. They can now do most things by themselves and will soon be completely cured.

Again, it’s not a great need.

An exception is made due to necessity, as when we are already involved in a very positive action, such as intense study and assisting a sick person would be a serious obstacle to it.

So, this is if you’re already doing retreat or intense study, you’re very involved in it, and taking care of somebody would really take you away from all of that for weeks or months or whatever. I’m thinking sometimes in the monasteries if a relative falls sick, they may call for the monk or nun, “Please come home and help your mother or father,” or somebody like that. The families are very close, so very often they do that. But there’s this kind of saying that if you’re involved in intense study and practice, it’s not necessary that you go home because that could take months by the time you get there and take care of somebody and come back. But try and get somebody else who is already there who is capable to take care of the family member.

I’m also thinking of situations where sometimes we may be in a public place and a total stranger is sick and what do we do? I was in a shopping mall with my parents one time in Hong Kong, and somebody had an epileptic fit. What do you do in that situation? There’s that kind of situation. Like if you’re traveling in India and you see other people who are traveling who are sick, you don’t know them—the Injis, the Westerners, really bond when you’re traveling together. Even if you don’t know people you bond together to help each other if somebody is sick.

Then it’s strange; you get off the train and if you see a very poor Indian beggar who is sick, you don’t stop to take care of the person—most people don’t. And it’s a hard situation; it’s really very complicated because do you take that person to a hospital even though you don’t speak the same language as them? Do you pay for everything that they’re doing? And what happens if their relatives are also beggars in the train station? They had a place at one of the Dharma centers in Bodhgaya where they wanted a clinic to bring people, like a hospital for them to stay. Many people didn’t want to go because a hospital is where you go to die and they would be separated from their family, so they would rather stay at home without treatment. You have all these different cultural things that you have to deal with and the language difficulties. What do you do? Here’s somebody with whom you don’t even share the language, so you can’t say, “I’m going to take you to the hospital and I’m going to do this and that.” They could be terrified if you just pick them up and put them in a taxi. You run across those situations. Then also, there’s twenty, thirty people like that in the train station, so it’s something to think about.

There’s a story in the vinaya about one monk who was sick and the other monks didn’t want to take care of him. I don’t know if he was too messy or dirty because he was sick and he smelled bad so they didn’t want to go near him. When the Buddha found this out he was really quite upset so he went and nursed that monk back to health. Then he really told the monastics, you have to take care of each other. When somebody is sick, you have to care for each other.

Audience: Is this also the case when there are monks and nuns together and there’s no one who could help them out, only nuns, for example?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): What’s a situation if there’s monks. A monk and a nun are in your proximity, do you help that monk? Are you talking like in a monastery situation?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Okay, so there’s monks and nuns all living in the Dharma center. Does a nun care for a monk or a monk care for a nun? It’s better to enlist the help of somebody who is the same sex as that person to help that person out because it involves going into their room, maybe handling their clothing or depending how sick they are and everything, it’s better to have somebody of the same sex do that. If there’s absolutely nobody, clearly you do that, but if there’s somebody else who can help. On the other hand, if there’s somebody who can provide a special service that other people can’t, if there’s a monk who does something to his back, Venerable Tarpa’s going to go help him. In that kind of situation that’s okay and you try and have somebody else in the room when you do that.

Have you ever been in situations where somebody has asked you to help them when they’re sick and you just don’t feel like doing it? Nobody has had that? What did you do?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: You ended up helping them and the others left. Did you ask the others to help you out?

Audience: No, it was a situation a long time ago. This person was dying of AIDS. He was a student of mine and he said, “When it comes to it, will you help?” I said, “Of course, I’ll support you.” And he said, “I have all these people lined up.” When it came down to it they really were gone and I didn’t know them. I was resistant because of the time it was going to take but in the end he really didn’t have anybody. So there I was.

VTC: So in a situation where somebody doesn’t have anybody, you help. In a situation where it’s possible to enlist others’ aid, you ask other people, “Please come and help.”

How about other people?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, right. I think it’s very clear to see what they expect you to do. If they’re expecting you to help them specifically or take care of other things that they can’t manage. What’s the time that they might need help for. Are there other people around who could help, neighbors or whatever, and to just be clear about it. But it’s also something to look sometimes at how we have some resistance.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Oh, because you didn’t feel that I was receptive to the help earlier.

Audience: No, it was a little more complicated than that. I actually don’t think I did as much as I could have from my side to resolve it.

VTC: But they’re healed.

So, especially in a community situation, it’s important to really try and take care of each other. And I’ve really seen that a lot in the community. Although I think in many ways we rely on Venerable Jigme to do it. We don’t go to see how somebody is or don’t bring them lunch because we expect her to do it. So, I think sometimes we should really check because maybe she needs a break and some relief.

The next section is not eliminating suffering but “Failing to alleviate suffering in general.”

Not removing others’ suffering: The previous fault concerns not helping the sick in particular. The present misdeed consists of not eliminating the suffering or problems with which beings are confronted in general. The same exceptions apply to both. As before, the misdeed is associated with kleshas—[with afflictions]—when it is motivated by anger and so forth and is dissociated from them when it is inspired by sloth or laziness.

And here it has specific groups of people:

Not alleviating the suffering the blind, the deaf, amputees and cripples, tired travelers, those suffering from any of the five obstacles preventing mental stability, those with ill-will and strong prejudice, and those who have fallen from positions of high status.

This brings up a whole lot of things, if you start thinking about it. Not helping the blind, the deaf, amputees, cripples, that makes sense, you know? If we’re out in public and we see somebody needing something, it makes sense to go and extend a hand if we can. But it also doesn’t specify how much suffering. Does it just help somebody open the door when they can’t get in? Or what happens if they’re also upset? And what happens if they need help doing whatever errand they’re doing? So the question becomes, how much do we change our plans and extend ourselves to help somebody else? That can sometimes be a hard one because we have something in our mind that we want to do and get done, and then something happens.

I know that they’ve done these studies sometimes where they check. There was a study where they tested people who were going to speak at a big hall, having something to do with benefiting others. On the way going there, they staged something where somebody was sick or fell or whatever, to stop and see if these people stopped to help them. And many of them didn’t. But it’s a tricky thing because at that point, do you feel that the needs of the whole group in the auditorium, maybe there’s a hundred people, are more pressing than helping one individual? You’re in a public place and maybe somebody else can come along and help them. But then, you think, well, maybe it’s worthwhile to stop a little and at least recruit somebody else to help that other person instead of just going on your way without saying anything. Same thing with traffic accidents. Sometimes you don’t know, do you stop and help? Or is what you’re going to do just going to be to get in the way and it’s better to wait for emergency services to come? I guess, there the best way to help is dial the emergency services.

But I was in a situation once, it’s kind of related to this. I was walking to DFF in Magnolia Village; there were two men outside arguing and one man just took the other man and slammed him into the wall. I was across the street and I thought there was going to be a big fight there. He might have slammed him in the wall twice. And I was thinking, “Oh my goodness, what do it do? As it happened, there were other people around and they called the police on the cell phone, but before the police could even get there, the man who slammed this guy had gone away. But you think in those kinds of situations, what do you do? Especially now when so many people have guns, do you even get involved if two people are quarrelling in public?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, those situations bring up a lot of questions. There was something in New York that happened earlier this year where somebody was robbing a pharmacy and an off-duty detective or somebody was there and went to help and he wound up getting killed. So, it’s really difficult nowadays to know how to help, when to help. Then like you were saying, in Germany they had the discussion on how to stop the young kids from getting the weapons, getting drunk and using them to start with. In America we don’t even consider that. Everybody has their right to carry arms, and their right to get drunk and…

Audience: Stand your ground.

VTC: Yes, it’s scary. I remember years ago, do you remember when there was some big public discussion because somebody was in New York calling for help outside of an apartment building and nobody went to help them? Do you remember that? And there was this huge public discussion and people were saying, “Look, we really need to go out when somebody’s crying for help, go help them. But I’m wondering if now because of all the guns, people are too afraid to do that and the way they help is to call the police.

Audience: Although part of being a good Samaritan is getting challenged or threatened, there are parts that want to do it but then there’s also the safety of one’s own life.

VTC: Right.

Audience: I also think about those stories where the good Samaritan gets killed gets in the paper. And, I’m sure there are many, many times still, where someone does help, and it doesn’t get in the paper because he doesn’t get killed and it works quite well. So, we don’t really know; it’s really so fear-based. I just was looking at the news before our internet went down and saw this very disturbing story about a line of clothing for carrying concealed weapons. Did you see that?

VTC: Yes, I read that.

Audience: You can get shirts and pants and very fancy with the hidden pocket so your knife and your gun won’t show. It was so extreme. But then I think this is not what most people are doing. It’s sad it’s out there and it’s bizarre in a way, it’s kind of the way this country, some parts of it, are going, but I don’t think the average person is going to run down and get a concealed weapon shirt. This is what gets in the news and what we’re drawn into listening to.

VTC: Yes, right.

Audience: I think what it does is we get used to it and the desensitization of how deplorable it is actually.

VTC: Right.

Audience: I have had had many experiences, even recently, of people stopping to help or I’ve had accidents and been a part of the people who helped in that situation. But not too many years ago, I had a flat tire. I’ve had many flat tires on the side of the road in my life and there was a time when people would just stop immediately, right then. On this particular one, I didn’t have a cell phone and so many cars went by in the middle of the afternoon before somebody finally stopped so I could ask to use their phone. It just triggered memories of how quickly aid can come earlier in your life, so I think people are not as quick to give because of the climate now—at least, that was my assumption. But I was surprised at how long it took. Because I was out there with a little white flag out…

VTC: It’s something to look at. What is the situation? How can we help? How can we help in a safe way? And so on. What does helping really mean? Even for the police—they hate domestic disputes because those are sometimes the most violent horrible things.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, more police get killed in a domestic dispute than in other ways, yes.

There’s a lot to think about in here, huh? Okay, then helping tired travelers, that makes sense. We should think about that here at the Abbey. That when people arrive we should offer them something to drink at least.

And those suffering from any of the five obstacles preventing mental stability—I think that’s like people who have a lot of grief, something that’s happened in their lives that there’s a lot of grief, they’re not so mentally stable, somebody’s facing a lot of loss. So, it’s saying to comfort people who are grieving, who are upset or angry about something. It’s very interesting because some people are more afraid of helping in situations of physical violence and other people are more afraid of helping when somebody’s emotionally upset. Then just the contrary, some people find helping others who are emotionally upset very easy, they don’t hesitate to do that. But to intervene, when there’s a physical confrontation, they really hesitate to do that. It’s interesting, isn’t it?

Audience: I was thinking how to deal with people and I was thinking this would be nice to learn how to deal with people who have difficulties, mental difficulties, for example, and physical difficulties.

VTC: Yes, in our situation we may very well find ourselves helping people with mental difficulties rather than physical difficulties and so to know how to do that would be helpful. This is something actually we can talk about. Sometimes I like bringing different situations that people write me about, discussing it at lunch and see what people would do. So, I can do that some more—share with you. That can be very very helpful.

And the first aid course that Venerable Jigme was doing. I know I need to hear it many more times so I get the confidence that if I’m in that situation, I know what to do besides say, “You in the plaid shirt, come,” and they come back here and help me. [laughter] Although they did make that point so we remember that one, yes? That’s good.

Those with ill-will and strong prejudice.

This one is for if somebody is really in a bad way, full of a lot of hatred and anger and spite and resentment, helping that person chill out a little bit.

Audience: Those are the situations where I don’t know whether I can help at all. When somebody’s really spouting off, especially in a prejudicial way, sometimes being in situations like that you just go, “My gosh.” Maybe with NVC now, after having watched what Marshal did in the story of the taxi cab. The taxi driver was really spouting off some racial remarks, so he talked about “I feel hurt.” I don’t even know what he was feeling but he was feeling and needing. Being able to address that person in that way really struck me because of having been in some situations where I didn’t know what to say, I didn’t know how to counter that person’s strong opinion but using NVC I can.

VTC: If somebody is saying something really mean and cruel, prejudiced or not, but they have so much emotion, especially if they’re angry, then sometimes you don’t know what to do. Sometimes actually it’s hard to communicate with that person. It depends how angry they are because they’re in this refractory period where they can’t take in any new information. But at other times maybe they’re just spouting off out of habit and they aren’t feeling it so strongly. Then using NVC, you could say, “When I hear words like that I feel very uncomfortable or I feel hurt,” or whatever it is.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes. When we’re not with people who are angry and especially people who are prejudiced, we always think, “Oh yes, when I run across those people I’m going to stand up and say something.” But when we run across them suddenly we go, “Oh, I don’t know what to say.” And they’re so angry, how can I even face that anger?

Audience: This is the one I have difficulty with. In that situation, I oftentimes don’t think the person is open, but I think this might be a way to make them open, to express your reaction, your feelings and needs and put a complete spin on it which they aren’t expecting.

VTC: Yes, right, because I think if you try and argue with those people about their ideas, they just often get more revved up. But if you talk about how they’re behavior is affecting you they have to switch a little bit and think of that.

Audience: Reverse the situations on them. My father was very prejudiced and he’d say things. I just say “when you say they should go back to Mexico or Africa, what if someone told you you had to go back to Ireland? It would be the same thing, Daddy.” And he said, “Oh, I guess.” When I finally put that out there in a compassionate, not a confrontational way, it was like “Oh, I hadn’t thought of that.”

VTC: Yes, good.

Those who have fallen from positions of high status.

So, it’s somebody who had a position of high status, maybe the stock market went down, maybe they got fired, maybe they were accused of something they didn’t do, who knows what? Then people are in mental turmoil and helping them. I think a lot nowadays that people we’re going to wind up helping is people who are getting divorced. Because so often people come and they’re just completely bound up because of a divorce situation, so it’s important to think about how to help them.

Audience: What this makes me think of, it’s a little different but one thing my father has said to me a lot recently is where he lives now, what he likes about it a lot is that you’re not losing your sense of identity. Because as people get old and they move into a nursing home, a lot of times they feel like they’ve lost dignity in the way they’re treated and this and that. I noticed that this is one really beautiful point about this place where they are, this thing of holding dignity and respect for people. It just happens a lot with elderly people who are losing their function in life.

VTC: You were talking about alleviating the suffering of others. It could mean with the elderly, giving them attention, respect and care because they so often feel like they’re pushed off and neglected. Last week when we were in the airport I was walking somewhere. There was one lady sitting in a wheelchair, she was just all alone and just sitting there like that. I walked past and I smiled at her and she didn’t know what to do. On the way back she was still there; I stopped and I said, “Do you need anything?” and she said, “No, I’m okay.” But I felt from my side “Boy, she looks so miserable and lonely in an airport.” So I don’t know. But treating the elderly with respect.

I think also treating inmates with respect, that’s one of the big things when we go into prisons. The thing that just touches the guys so much is that we treat them the way we normally treat people, they hardly are ever treated like that. Even when we write letters, just treating people in a respectful way. Not writing hateful, spiteful, blaming things.

The next one is in the section on “Not eradicating the causes of suffering, so it is not showing those who are careless what is suitable.” And here it says, “Not teaching the reckless in accordance with their character.” It’s similar but not exactly the same. And another way it’s said is, “Not explaining what is proper conduct to those who are reckless.” They are all slightly different wordings. It’s interesting, and it gives you a different perspective on it.

We see people who clearly do not know how to behave with regard to this life or future lives. They are apparently unable to determine what is in their best interests and what they should preferably avoid doing. When we see people who are on the brink of making a serious mistake, or who have already made one, it is our responsibility to do our best to point out their error and to give them good advice. We must show them what is right in a manner that corresponds to their abilities. If they are doing great harm to themselves or to others and we fail to say anything to them due to our feelings of anger or animosity towards them, the misdeed is associated with afflictions. It is not associated with afflictions when our inaction is due to sloth or laziness.

It’s interesting that he never mentions fear in any of these. Sometimes people are very afraid of helping the sick, they don’t even want to go into the hospital to visit Aunt Ethel, they’re afraid of the hospital or afraid of seeing anything ugly. It’s interesting that fear is never mentioned here. Yet I think in terms of helping the suffering, very often that’s one reason why people don’t help; they’re afraid. We were just talking of being afraid because of physical conditions, but also being afraid of somebody’s anger, being afraid of feeling intimidated ourselves. Some people really freak out when they see other people cry, they can’t handle it. They don’t know what do to, they’re afraid of it. It’s all sorts of things like this.

Audience: You may make a mistake and cause more harm than help.

VTC: Yes, being afraid to make a mistake and cause more harm.

Audience: I think there’s never going to be a solution. With addiction, mentally-ill people, it’s like they just suck you in more and more.

VTC: Yes, you’re trying to help somebody where you feel that there isn’t a lot that you can do or where you’re going to get sucked in and it’s going to be more than you can handle. Like you said, sometimes it might be helping somebody who has an addiction or somebody who is mentally ill. But then I think at those times we really need a lot of clarity about what is helping them. We may try a certain kind of help and if that doesn’t work, we know that those people need professional help. Then helping them means getting them to the place where they can get the professional help.

That’s something to really hold in mind. I remember I was living in one Dharma center when somebody came there who was on meds for some mental illness. The guy in the kitchen thought it would be so great to get her off the meds and have her just be happy without the meds. She stopped the meds and then she was running up and down the corridors naked. So, you really have to think, what does it mean to help somebody? In her case what happened is the center had to call her family and say, “Please come and help her.”

So, in all this thing about helping others, it’s important to really sit and think about what is help and what isn’t; when do we intervene and when don’t we? This is true especially in situations of addiction, let’s say, and it depends on the relationship with the person. If we know that they can be very manipulative and that we fall for it, it may be better that we don’t try and help them. On the other hand, maybe we should also try to improve ourselves so that we don’t fall for that kind of manipulation—so that we can remain strong and steady and clear. That’s the best thing to be able to do. But these things can really be quite challenging.

Here it’s talking about maybe somebody who is about to do some great negative karma, who has just committed negative karma and trying to talk to them in a way that they can understand it. When I walked around Green Lake, I used to see all these people fishing. Clearly I can’t go up and say, “Please don’t fish.” I could but I don’t think it would go over very well. There’s those situations, but maybe there’s another situation where it’s a relative who is going out fishing. Do you feel okay going to that relative and saying “Fish want to live,” and so on, or do you not even try because you’re afraid? You assume that they’re going to get mad at you so you don’t even try saying anything.

It’s hard sometimes. Or if when you’re with people, especially in families at a work situation, where one person is bad-mouthing another person and scapegoating another person, how do you deal with that skillfully? Because sometimes if you try and stick up for that person, the other people get even angrier, and if you tell them, “Don’t talk like that,” they also get angry. In this way I think NVC can be helpful because if you just state how that kind of speech affects you, then maybe there’s a chance that they can hear it, maybe not. But in so many of those situations, we don’t do anything because we’re afraid of what other people are going to think of us, aren’t we? Are they going dislike me? Are they going to turn and criticize me? So, we back away, and we don’t even try. Maybe we need to think creatively about how to handle these kinds of situations.

Audience: I think it’s very helpful in those situations to try and just change the subject. Like sometimes, if they’re really wound up, and it looks like they’re not going to back off or something, and we don’t really want to deal with all that, then we just change the subject or say, “No, I need to go now.” Because sometimes that’s the most skillful thing you can do.

VTC: Yes, if it’s a one-on-one conversation, sometimes the best thing is just to exit, say, “I have to go.” But sometimes when you’re with a group, you can protect your own mind by leaving, but it’s not stopping the others. In this one I think you have to have a special kind of relationship with somebody to be able to give them this kind of advice and to have them hear. Because people so often don’t like being corrected. But I’ve also had the experience where I think, “Oh, I don’t want to say something; they’re just going to get mad at me. They’re going to get defensive—blah, blah, blah.” But I make myself say something and afterwards the person says, “Thank you so much. I really appreciated that you said that and that you warned me.” Then I realize, “Oh, all my fear is really stupid.”

There’s some exceptions to this one.

The first exception concerns the subject—[which is us]. We do not know what is best for the other person or if we do, we feel incapable of communicating it properly. In those kind of situations, it’s not a fault not to help the reckless. Two, we leave the person in the hands of someone who is better at explaining these matters than we are.”

Sometimes that is a good solution. If we can’t help, introduce them to somebody who can or put them in the care of somebody who can.

There are four exceptions in relation to the object—[the people to be helped]. One, the people are perfectly capable and have sufficient knowledge to find the solutions or choose the right course of action themselves.

That would be assuming that you’re dealing with reasonable people who really aren’t so reckless.

Second, they have qualified spiritual masters or teachers to guide them.

You see somebody who is about to make a big ethical mistake, maybe breaking a precept or something, and you know they have teachers to guide them, but still, it really depends on the situation because sometimes that person is not near their teacher. Sometimes they are but the person doesn’t want to go their teacher to ask for help and often, at least with Tibetan teachers, they won’t say anything at all. Then the person just does whatever. So, sometimes we might have to speak up more but try and be as tactful as we possibly can.

Three, they are aggressive and hostile and would most likely take our suggestions badly or misinterpret them. And four, they are fundamentally disrespectful and unappreciative and would disregard our advice or react adversely to it.

But some of those are really assuming that we know how the other person is going to respond.

An exception is made out of necessity when it is better for the people in question not to receive our advice because it will force them to think, to question themselves and so on.

So, it’s saying to not intervene when we know the person is capable of figuring the situation out themselves and that they need to really exercise their mental muscles to do that.

Audience: I wonder what you think about the cultural aspects of our psychological character in the West versus in the Tibetan culture.

VTC: Your question is about helping people with mental illness, and the difference in psychological models between Tibetan culture and Western culture. Yes, there is a big difference. In a Tibetan culture when somebody has mental problems they take them to a lama to do puja because they think that they have spirit interference or something like that. They’ll do the puja and sometimes the person gets better. In our culture, that doesn’t always work so well. Some people might do that, but many people work on a very different psychological model and want psychological talk therapy. Then other people just want to take those people and give them meds. Much, I think, is involved in the culture.

I was reading once about women in, I think it was in Malaysia, many years ago. The culture was such that middle-aged women weren’t allowed to really express their feelings when they were unhappy about something. So, very often what they would do is they would just have some episode where it looks like they’re completely out of control emotionally, and they would be treated for having a spirit offense but in the process, they would say what it was that was bothering them. Other people could hear it and after they got the remedy for the spirit offense, they calmed down. It could be that that’s what they had to do because otherwise their needs and concerns wouldn’t be heard in the society.

Actually, when I was in Dharmsala one year, I was sharing a room with somebody who was doing anthropological research. She had a young Tibetan woman who was translating for her. This young Tibetan woman was in love with somebody at the TCV School but her parents wanted her to marry somebody else. She tried to say, “I don’t want to marry that guy. I don’t like him, and I want to marry this guy instead,” but the parents wouldn’t listen. And she had what my friend thought was a nervous breakdown. But in her parents’ mind, they took her to the lama. She was saying, “I don’t want to marry this other person; I want to marry this person.” She was acting like this, so the lama did a blessing or something, and she calmed down. The parents heard what it was that was freaking her out so much and then they said, “Okay, you can marry who you want to.” It’s interesting how things come out in different cultures when people don’t have avenues to express themselves. It’s the same with psychosomatic illness, which people have in this culture. When they can’t express things it often comes out in a physical thing. Then somehow what’s really bothering them can come out.

Audience: Before the women’s lib movement, women would have nervous breakdowns; that’s what they did. Even they got put on tranquilizers so they didn’t feel anything. They spent a lot of time in psychotherapy talking about what they didn’t like. I remember that in the 50’s and 60’s it was just real common.

VTC: Yes, when you aren’t given space to express something—when it’s not socially acceptable—then it comes out in other ways. It depends again, on which culture we’re in, what kind of person we’re going to help. Some people are brought up in cultures where there’s a lot of shamanism, and they feel their good energy got taken away or somebody did black magic on them or whatever, and we have to explain things according to their paradigm. This happens a lot in Singapore. The people there really talk about spirits and black magic. It’s a modern culture but there’s still very much that in their culture. And in certain pockets in our culture, too. And you have people in our culture who go to the other extreme and say there’s nothing psychological—just give them a pill and that’ll solve the problem.

When you’re thinking about this and you come up with situations in your life that apply to this, bring them up to the community. Because I think it can be really helpful if we discuss specific situations and how to act and help people in those specific situations. It helps us all learn new skills and become a bit more creative because we all have different backgrounds, so we know how to help in different situations.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.