Bodhisattva ethical restraints: Vow 18 and auxiliary vow 1

Part of a series of talks on the bodhisattva ethical restraints. The talks from January 3 through March 1, 2012, are concurrent with the 2011-2012 Vajrasattva Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey.

- Four binding factors which need to be present for a complete transgression to occur

- Vow 18 is to avoid:

- Abandoning the two bodhicittas (aspiring and engaging).

- Auxiliary vows 1-7 are to eliminate obstacles to the far-reaching practice of generosity and obstacles to the ethical discipline of gathering virtuous actions. Abandon:

- 1. Not making offerings to the Three Jewels every day with your body, speech, and mind.

- 1. Not making offerings to the Three Jewels every day with your body, speech, and mind.

NOTE: There is sound from beginning but talk starts at 3:00

Motivation

While we often say that we’re extremely fortunate for having this precious human life, simply rejoicing at having a precious human life isn’t sufficient. Now that we have it, we have to make use of it. We always say that the best way to make use of it is to generate the bodhicitta. But to do that, we also have to subdue our ignorance, anger, and attachment. In our day-to-day life we have to be very aware of what’s going on in our mind and how the intentions of our mind manifest in external actions. And when we see an affliction in our mind, we need to do something about it.

In other words, this means to not just say, “Oh well, there’s laziness, there’s attachment, there’s anger—my mind is so full of afflictions.” And that’s it. We have to notice it, but then also try to apply an antidote. And if we apply antidotes, at first it may seem like we’re not getting anywhere. But with time, as we practice, we are successful. We see a change in our mind, and the people around us also see that change. When we’re motivating for bodhicitta or with bodhicitta, for the benefit of all beings and to attain enlightenment, we’re also making a commitment to do something about that. So, it’s really trying to oppose our afflictions and cultivate our good qualities. To learn how to do that, we’ll talk about the bodhisattva ethical restraints.

18. Forsaking bodhicitta

We’re on the last of the 18 root precepts. This 18th one is from the Sutra for Skillful Means, and it says, “Forsaking bodhicitta.” You can see how, if this is the whole series of ethical restraints that we take, motivated by bodhicitta, if we forsake bodhicitta, something’s really wrong. You can see why this is a major downfall.

This major transgression consists of giving up aspirational bodhicitta.

Do you Remember? We talked about two kinds of bodhicitta: aspiring and engaging. Aspiring wants to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all beings, and engaging is committed to doing that, and is actively doing that.

We differentiate between the conventional or relative bodhichitta—the aspiration to become a Buddha for the benefit of all living beings—and the ultimate bodhicitta, which is the realization of emptiness.

We may talk about aspiring and engaging bodhicitta, but those are both sub-divisions of conventional bodhicitta. We also have the ultimate bodhicitta, which is the wisdom realizing emptiness. “This misdeed involves the conventional bodhicitta, which has two levels: aspirational bodhicitta and engaging bodhicitta.”

The Great Way explains that the fault is made in relation to aspiring bodhicitta and that the basis for forsaking [aspiring bodhicitta] must be someone who has the bodhisattva vows.

Clearly you can’t forsake it; you aren’t going to break this root vow if you don’t have it.

We forsake our aspiring bodhicitta when, for example, we make an exception for a certain person and think, ‘He is such a nuisance that I will never help him gain freedom from samsara. He will have to manage without me!’

It sounds kind of stupid, but sometimes we get really mad at people, don’t we? I mean, we get really mad. And besides saying, “He can go burn in hell,” and all the other sweet things we say when we’re really mad, if somebody came up and said to us at that time, “Are you going to lead him to enlightenment?” we would go, “Beep-beep-beep-beep-beep.” We’re certainly not in any mood to do anything for that person except cause him suffering, because of what anger is like. So, you may think, “Oh, giving up bodhicitta: I won’t do that.” But think about times when you’ve been really furious, really furious. And at that time, if somebody said, “If you want to attain enlightenment for this person, do you want to go to the lowest hell realms to benefit him?” what are you going to say?

Audience: He goes first.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Yes, exactly!

As regards the object, it makes no difference who we exclude. It can be any living being, human or otherwise. It can even be an evil spirit.

It doesn’t matter if the person is somebody who has been kind to us or mean to us. It doesn’t matter how they’ve treated us; it’s our forsaking them.

Bodhicitta is the aspiration to work towards the happiness of all living beings without exception and therefore abandoning just a single being is completely inconsistent with it.

That means, when you’re sitting in the house and there’s a stink bug crawling around, to look at that stink bug and say, “I’m depending on that stink bug to generate bodhicitta and become a Buddha.” It’s true, isn’t it? If we don’t include that stink bug in our bodhicitta, there’s no way we’re going to become Buddhas. So, all of our adorable hornets and wasps and bees and yellowjackets and ants—the stink bug is a cinch, but some of these other ones are tougher. Not to mention human beings, what they do. So, this means to really look at everybody and say, “My enlightenment depends on that sentient being.”

The action is thinking from the bottom of our heart that we will never help a certain being again, no matter what happens. As soon as we entertain such a thought—

I don’t think it’s just “entertain,” like it flashes through our mind, but rather, it’s that we’re having a good entertainment session where we’re very involved in the thought…

—the transgression is complete, and we immediately lose our bodhisattva ethical restraints. The presence of the four binding factors is not necessary. However, it is not a matter of making a casual remark like, ‘I can’t stand him,’—

Because we do that all the time. It is not very compassionate.

—we must be truly determined never to do anything to help a certain being again.

We have seen that two major transgressions alone do not require the presence of the four binding factors to constitute a major misdeed: the ninth, holding wrong views, and the eighteenth, forsaking bodhicitta. In these two cases, we lose the bodhisattva ethical restraints even when the four binding factors are absent.

It is very clear in this case, especially with the ninth and the eighteenth. We don’t have to say anything. We don’t have to do anything physically. The major downfall can happen in our mind, just by the way we are thinking.

The Four Binding Factors

Now we’re going to look at the four binding factors. The first one is:

Not considering the action to be wrong.

Second is:

Not wishing to abstain from the action in the future, but rather wanting to repeat it.

Third is:

Taking pleasure in the action and delighting in it.

Fourth is:

Feeling no sense of integrity or consideration for others.

Not regarding one’s action as negative or not caring that it is, even though one recognizes that the action is transgressing a vow.

This other text has a slightly different interpretation. Two is: “Not abandoning the thought to do it again.” Three is: “Being happy and rejoicing in the action.” And four is: “Not having personal integrity or consideration for others regarding what was done.”

We also find these four binding factors in the six-session guru yoga. They’re in there.

Sixteen of the eighteen root transgressions are major transgressions only when the four binding factors are present from the beginning to the end of the action. For example, when we make the mistake of praising ourselves or looking down on someone, the transgression occurs only when what we say is accompanied by the four binding factors from the moment we start talking until we stop.

So, we’re going to look at the four binding factors.

1. Not considering an action to be wrong.

Let us continue with the example of praising ourselves or denigrating someone else. We see someone being given a valuable gift, for example, and we are jealous. We don’t like the idea that this person is receiving it and we are not, because we want it for ourselves.

Maybe a donor is giving something nice to somebody else in the monastery, and you think, “That person already has that, and I really need it, and how come they’re not giving it to me? This person always gets the good stuff, not me.”

Motivated by greed and jealousy, we look for ways to prevent the person from obtaining it. So that we may be given it instead, we make disparaging comments about the person or extoll our imaginary good qualities.

“Oh, so-and-so, they already have that, and they don’t treat it very well, they don’t need it. They don’t take very good care of their stuff. Anyway, I’m a much better practitioner. You should really give it to me.” We’re not that blatant, are we? But we find our own little ways to let it be known how good we are.

We see no wrong in doing this and feel perfectly justified in what we do.

Because, after all: “That person already has something” and “They are not a very good practitioner. Why should they get it and not me?” So, we feel perfectly justified: “What I’m doing is not wrong. It’s actually kind of good, because I’m protecting this benefactor. Otherwise, they’re going to waste their money giving this offering to that person, when they could actually create some merit by giving it to me.” [laughter]

We might think that we deserve the present more than the other person does and, therefore, have every right to ensure that we get it.

Or maybe it happens with a sibling. We’re jealous of what a brother or sister is getting and think, “They don’t even practice the Dharma. Why should they get that and not us? We’re all part of the same family, and our parents, or whoever it is, should give it to me because I’m the one who practices the Dharma. All my brother or sister do is waste their good karma.”

It is possible, however, that as soon as such thoughts arise in our mind, we immediately become aware that they are blame-worthy. If we change our mind in time and consider what we are doing to be wrong, the first binding factor is absent.

So, you’re right there, the mouth is open, the words are about to come out, and then you go, “Hmm, maybe I need to reconsider this.” And you close the mouth. Then, if you completely abstain from the action, there’s not going to be a break whatsoever. But let’s keep going here.

Imagine that we have already said what we intended to say, we didn’t close our mouth fast enough, and it is only a moment later that we realize that we have done something wrong. In this case, there are several possibilities: The person does not immediately understand what we say and asks us to repeat ourselves. If we abstain, an element is missing.

So, we say, “Oh, nothing. I didn’t mean it anyway.”

Since the first binding factor is lacking, the misdeed is incomplete. If the other person understood what we said the first time, the action is already complete with the first binding factor. Realizing that what we have done was wrong after the fact is too late to prevent the transgression. We see that it sometimes is an advantage not to speak a language well, for our comments may not be immediately understood by others! In these circumstances, if we realize our mistake in time, we can avoid a major transgression.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): This is one of the reasons we keep silence during retreat. Because when we keep silent, those things don’t come out of the mouth. Also, when we keep silence, we notice all the urges we have to speak. So much of it just comes into the mind, “I want to say something.” It usually comes out of our mouth without thinking. When we have times in our life when we keep silent, it makes us much more aware of those urges to speak. We get some time to really consider, “Oh, is what I’m saying necessary? Is it necessary? Is it advantageous? Or is it just blah-blah. Or even worse, is it transgressing my precepts or damaging someone else?”

2. Not wishing to abstain from the action in the future, but rather wanting to repeat it.

Since we do not see anything wrong with what we do—

That’s the first binding factor.

—we do not have the slightest intention to try and avoid doing it again. On the contrary, we plan to repeat in the future what we have done in the past.

So, there’s no wish to abstain from doing it at all.

We can see why the first one is the first one. If we don’t think what we’re doing is wrong, then we’re not going to want to abstain from it. We will rejoice in having it, and we won’t have any integrity or consideration for others, because we don’t think that we’ve even committed a fault. What is very tricky about this is that the times we transgress these precepts are the times that we have no idea in our mind that we’re transgressing them. It may only be well after the fact that we look back on what we said, or what we did, or what we thought, and we think “uh-oh.” But at the time, to have the four binding factors complete, we have no idea that we’ve even broken a precept, because we don’t consider what we’re doing to have any fault.

Part of that way of thinking could come from ignorance, because we don’t know what the precepts are. Part of it could come simply because our mind is so obscured. Part could come because we’re so overwhelmed by afflictions. We just see, “Oh, if I say this, I’m going to get some benefit,” that the thought doesn’t even enter our mind. Maybe we’re reckless. Maybe we’re just out to lunch. We are overwhelmed by afflictions. We don’t know what the precepts are. You can see how this happens.

3. Taking pleasure in the action and delighting in it.

This factor has two aspects: a feeling of joy and a feeling of delight. The first term, joy, refers to the pleasure we experience at the prospect of doing the action and in its preparation.

“I’m going to get this offering. I’m just telling the person the nice thing, the good qualities that I have. I’m not lying or anything. It’s not a major downfall of my monastic vows. I’m not lying about my attainments. I’m not even saying I have attainments; I’m just telling them how well I practice. There’s nothing wrong with that; it’s true.”

The second aspect designates a feeling of delight regarding the activity in general. For example, we may love to talk about our supposed talents or accomplishments. We like the idea of it. We enjoy it when we’re doing it. We’re glad of having done it.

Even taking something that belongs to the Three Jewels: “Oh, there’s crackers on the altar. They’re going bad, so I might as well take them. It will save the person who has to take the altar down at night from having to do it. And I’m hungry. So, it fulfills two purposes. And they won’t get stale overnight.” It all seems very good: “The monastery has lots of these things. They’re not going to miss it if I take something that I need.” Or whatever we feel like, you know—rummaging through those office drawers.

4. Feeling no sense of personal integrity or consideration for others regarding what we’ve done.

Personal integrity in Buddhism relates to oneself and is based on a feeling of self-respect. We have scruples about an action because we feel deep in ourselves that it is not right and not worthy of us who have taken the bodhisattva vows. The sense of integrity has a restraining effect and prevents us from engaging in wrongdoing.

Consideration for others is similar, except that it is others’ feelings that we take into consideration. It is in relation to others that we feel shy about the action we were contemplating and uncomfortable at the thought of what good and decent people would think if they knew about what we were planning to do.

He translates that as “shame” and “embarrassment.” I don’t translate it as shame, because shame is a really loaded word in English, and often connotes this sense of deep personal unworthiness, like being defective goods. That’s not the meaning of it. It’s more the kind of shame of when you know what you’re supposed to do, and you don’t do it. Because that word shame is so loaded, I don’t use it. I think personal integrity gives us a much better feeling for what it means. With “personal integrity,” we have a sense of ourselves as a person who is worthwhile, trying to keep good ethical conduct, and trying to keep our precepts. We respect ourselves. We don’t want to do anything antithetical to our own internal values and principles, because we have a sense of integrity, a sense of self-respect.

It’s similar to the term “embarrassment”; I prefer “consideration for others.” With embarrassment, I usually think of when you drop something all over the floor and you feel embarrassed—that kind of feeling of embarrassment. This is a little bit different. It’s a feeling, but with integrity. It is based on our own self, how we feel about ourselves. We want to be a person with good ethical conduct. Consideration for others is considering first how our behavior is going to influence somebody else. It may make them lose faith in the Dharma. It may make them lose faith in humanity, or who knows what. Also, we feel like “These are people who are wise. I don’t want to behave like that in front of them.” I don’t even want to behave like that behind their back. If they find out then I just won’t feel good about myself for what I’m doing.

So, we refrain from negativity as a result of considering the effect of our actions on others—whether they are ordinary sentient beings or wise beings who we certainly don’t want to offend. This isn’t attachment to reputation. It’s not like “Oh, they’re going to think I’m a bad person and talk behind my back”; it’s not that. It’s like “Wow! What I do has an effect! If I harm other sentient beings and make them lose faith, that’s not good. If I do something that wise people are going to look at and say, ‘What’s going on with her?’ I don’t feel good about that either.”

These two mental factors are very important ones to cultivate, because they’re the ones that keep us from not only breaking precepts but doing any kind of negativity. It’s quite important to cultivate these two.

As we are committing the transgression or immediately afterwards, if we feel just slightly a sense of personal integrity or consideration for others, although it may not be enough to stop us from doing the action, it is sufficient to prevent the transgression’s completion.

If while you’re doing it you feel like “Yikes, what am I saying? This is not good,” then the transgression isn’t complete.

If it takes an hour or so to realize what we have done is wrong and to feel embarrassed by it, it is too late. It is not necessary to feel both integrity and consideration for others; one of the two is enough.

The fourth binding factor implies, therefore, a total lack of integrity or consideration for others about what we are doing or have just done: “I don’t care!”

You look perplexed.

Audience: Well, I don’t understand the first example—if you get it out of your mouth and then you realize you shouldn’t have said it, he says that’s too late. But already all four are not present there. Right? Because even if it’s already out of your mouth, and you say it’s not too late…

(VTC): No. He’s saying if it’s out of your mouth, unless you have some awareness of it being wrong, or some wish of not wanting to do it again, or some lack of delight, or some consideration or integrity, if you don’t have that before the action is finished, or up to a couple of minutes, a minute or so afterwards, then the action is complete.

Audience: So, regretting it afterwards or anything like that doesn’t…

(VTC): Yes, if you regret it later on, it’s good, because then you’ll do some purification, but you still broke the precept.

Audience: Well, see, that’s the part I don’t get. If I said what I didn’t want to say, and then I heard it and went, “Oh, my goodness,” then I don’t rejoice, but this is afterward. Now it’s out of my mouth, but I’m not rejoicing that I said it.

(VTC): Right. If it happens immediately, and part of your regret is going on while you’re saying it, then it’s not complete.

Audience: Okay.

(VTC): Because he said that from beginning to end, these four must be there. If before you finish saying it you have this feeling of “Oh, what am I doing? This is not good,” then one of the factors isn’t there. But if you get done saying it, and you feel very satisfied, and then you go, “Oh!” immediately afterward, then maybe it’s not a full transgression. But if it takes you some time to realize it then the transgression has been completed with the four binding factors.

Depending on which binding factors are present, we commit a complete transgression, a medium fault or a lesser misdeed. If the four binding factors are present and all other aspects of the action as well, then the deed is complete, which means that we lose our bodhisattva vow. If the first factor, not considering the action to be wrong, is present and the other three are lacking, it is a medium fault. If the first factor is absent—if we are unaware what we are doing is wrong—and the other three are present, we commit a lesser fault.

As soon as you have the first one, it’s going to be hard not to have the other ones. You might have a situation where you know what you’re doing is wrong, but your afflictions are so strong. That could be an example of one. You know what you’re doing is breaking a precept, but the afflictions are so strong, you wish to abstain from doing it again. You don’t take joy in what you’re saying. You feel kind of bad about what you’re doing. But the affliction is so strong that it pushes you through. In that case, that would be an example of the first factor being there, but not the others.

As long as we are aware that our action is wrong, even if we still do it, we avoid a complete transgression. The first binding factor, the impression that what we do is not wrong, is the worst. Based on the awareness that the action is negative, integrity and other positive mental states can arise.

Audience: I find it difficult. It seems like sometimes I have so much foggy mindedness that sometimes I don’t even realize. It’s like when I took the highest tantra in Vancouver; I didn’t know what I was doing, and then I was not breaking the vows. Maybe I don’t explain it properly. But I had difficulty with that, how come? Not being stupid but…

(VTC): When we have obscuration in our mind, we’re not realizing what we’re doing. When you gave that example of taking a highest class tantra initiation and not realizing what you were getting into, I don’t think that’s simply through your obscuration. It could also be because people did not explain it well enough to the audience, and they did not know what they were doing. It happens a lot. Or you get pressured to take an initiation. You don’t understand what’s going on, and what the other person is saying to you sounds good. That kind of thing is a lack of adequate information. There are other times when we just have so much obscuration in our mind. That is when somebody says to us with kindness, “Oh, please take care of this behavior. Look more closely at what you’re doing.” We go, “What in the world are you talking about? What I’m doing is perfectly alright.” There is no awareness. Our mind is too obscured to even see that what we’re doing is damaging.

Audience: But I still break the vow, right?

(VTC): You mean in the case of taking an initiation without knowing what you’re doing?

Audience: Like the other day, I picked up a plate with a lot of anger: “You’re late!” My mind went, “You are late!” It was done.

(VTC): Okay, when you pick up a plate with anger, you’re not breaking a bodhisattva vow.

Audience: I’m not?

(VTC): Anger is not virtuous. You have to look at exactly the instances of anger and so on that are being discussed when we talk about these different vows. There’s a section in here about the ones that we do out of anger. Let me read it to you. You can see if any of them fall into that.

Here are the ones that you do primarily with anger:

Returning insults, anger, beating, or criticism with insults and the like; neglecting those who are angry with you by not trying to pacify their anger; refusing to accept the apologies of others; and acting out thoughts of anger.

So, you might be really angry and think, “Oh, I’m so late! ” and you pick up the plate.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes. It’s a non-virtuous thought, but you’re not breaking a bodhisattva precept. I think that’s what it is talking about here.

Acting out thoughts of anger is, I think, much more. For example, you’re angry at someone, and you really want to do something to harm them. Don’t get too hard on yourself and think that everything you do is breaking a precept.

Audience: You don’t see me all day, Venerable.

(VTC): Yes, but the Abbey is still standing, and everybody else is still talking to you. So, I don’t think you could be that bad. If you were as bad as you think you are, none of these people would be your friends. They are all your friends. I hope. Your anger hasn’t burnt down the Abbey yet.

Audience: No, not yet.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Yes, I think in that kind of context—even if it’s not another person, but you’re so angry that you’re violent and start smashing things then I think in that case you would break it. But it’s not just a thought of anger flashing through the mind.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): In these precepts, there are some precepts that involve us saying something to someone, like teaching emptiness to somebody who is not prepared. There has to be somebody there who is listening. If you are just in your own room, or you’re talking to the squirrel or the cat, then you’re not breaking the precept. So, you can teach emptiness to Karuna and Maitri all you want.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): You have to look at which ones. Breaking them requires somebody to hear and understand what you’re saying. Not all of them require that. Some of them do.

We can see that, in general, thinking something doesn’t take as much energy as when it comes out of our mouth. When it comes out of our mouth, the mind has already moved—plus there’s the energy of it coming out. We do it physically. It takes even more effort. That’s why we start out with the Pratimoksha precepts; they’re helping us to refrain from physical and verbal misdeeds. Those are much easier to stop than the mind. We really work with not letting this stuff come out—that’s a step in the right direction.

Consider that before we met the Dharma, the anger entered our mind and came out of our mouth a nanosecond later, didn’t it? That’s true for most of us, before we met the Dharma. It was complete, like this—flash! It was in our mind, out the mouth. Now, at least, it’s like, in the mind but not out the mouth. That’s progress, isn’t it? That’s progress! Even if the steam is coming out your ears, you’re still making progress. As we do that, after a while we begin to be able to catch the anger sooner and sooner. As we do more of the bodhicitta meditations, the cause for anger becomes less and less, because our mind becomes more flexible. We become more open-minded. It dawns on us that, “Gee, not everybody is going to do what I want them to do, duh!” When we have that thought in our mind, then it really helps us not get angry. So, we’re definitely making progress.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): Right. Let’s say there are these angry thoughts. One of them is retaliating when somebody insults us. Somebody insults us, and it’s like, “Who does this guy think he is? I’m going to insult him right back!” And at that moment we think, “Oh, but I’m a Dharma practitioner, I don’t really want to act this way.” That’s personal integrity. That keeps us from doing it. Or maybe we’re about to insult the other person, but some guest is here, and we think, “Wow! If I talk like this to another member of the Abbey and the guest hears it, they’re going to wonder what in the world is going on in this place. I’m going to disturb this person’s mind and disturb their faith in the Dharma. So, I think I’d better be quiet right now.” That’s consideration for others.

Let us assume that knowingly we are about to commit a transgression. We start doing it nevertheless, but in the course of the action, before it’s completion, we feel integrity and stop. This illustrates the very function of integrity, allowing for the abstention from misbehavior, the absence of which constitutes the fourth binding factor.

That was actually the answer to your question.

The ‘Great Way’ mentions further factors that may cause exceptions. For people to commit major transgressions of the bodhisattva vows, they must have taken the vows—

So, they must have the precepts.

—and not let them degenerate.

Because if they degenerated their precepts before by breaking one of the eighteen major ones, they no longer have them, so they can’t break them.

You cannot break a precept that you do not have. Furthermore, they must be in a normal state of mind, not mentally ill.

If somebody is completely in a psychotic state or entirely flipped-out, then they didn’t do it. It’s the same with the precepts of individual liberation: if you’re temporarily insane, then it’s not a full break.

They must not be in severe physical pain or in a state of great mental distress.

You can see there’s some compassion working here. If somebody is in incredible physical pain, they’re not able to control what’s going on with their body, speech, and mind. In the same way, if they’re just totally crazy with grief or some kind of mental distress, they really can’t work with their mind. Now, that doesn’t mean that as soon as I get angry I can think, “Oh, I’m in a state of great mental distress, so I’m not doing anything wrong. That didn’t break the precepts. My mind is just distressed with anger. That’s all.” No! That’s not what’s meant.

Audience: [Inaudible]

(VTC): You’re asking if with the other kinds of precepts there’s also this thing. Yes. If somebody is insane, or in a situation where somebody’s holding a gun to your head and saying if you don’t do this, I’m going to kill you, or you’re in great mental distress, incredible physical pain, or something like that, then it’s not a transgression of the precepts. The Buddha is compassionate.

Among the three bodhisattva ethics, refraining from the eighteen transgressions just described constitutes an essential part of the ethical conduct of abstention from wrongdoing. What are the other two types of ethical conduct? One is collecting virtue and benefitting others. So, there’s abstaining from non-virtue, collecting virtue, and benefitting others.

The 46 Secondary Misdeeds of the Bodhisattva Vows

The 46 secondary misdeeds of the bodhisattva vows are classified according to which of the six far-reaching practices they violate, with a final category of faults contrary to the ethical conduct of helping others.

That means there are seven categories: ones that are opposite to generosity, ethical conduct, fortitude, joyous effort, meditative stability, wisdom, and, as the seventh one of benefiting others. So, these are the seven categories of the secondary or auxiliary vows.

Another way to classify them is according to the three bodhisattva ethical conducts: the ethical conduct of abstention from wrongdoing, the ethical conduct of collecting virtue, and the ethical conduct of helping living beings.

So, you can also break them into those three.

In this case, 34 of the 46 misdeeds relate to the first two types of ethical conduct and 12 to the third. We will follow the first system, which is the most common.

In Pearl of Wisdom, that’s the system that’s being followed there, too.

Seven secondary misdeeds conflict with the first of the six far-reaching practices, generosity. Nine conflict with far-reaching ethical conduct. Four with far-reaching fortitude. Three with far-reaching joyous effort. Three with meditative stability. Eight with far-reaching wisdom. The remaining twelve conflict with the ethical conduct of helping others.

What is the main difference between the 18 major transgressions and the 46 secondary misdeeds? The 18 major transgressions or downfalls are so called because they discontinue the bodhisattva vows. Committing any one of them implies losing our bodhisattva ethical restraint, while performing a secondary misdeed, although contrary to the bodhisattva ethical conduct, does not make us lose the bodhisattva ethical restraint.

As with the eighteen transgressions, only a person who has taken the bodhisattva ethical restraint and keeps it, who is sane and not deathly ill or suffering from severe mental distress, can commit the secondary misdeeds.

So, those same exceptions hold for these, too.

The Seven Misdeeds Contrary to Far-Reaching Generosity

In Buddhism, generosity is described as the intention to give, and it can be of three kinds: one, the intention to give material goods; two, the intention to give protection or fearlessness; and three, the intention to give the Dharma.

Sometimes, they also include the intention to give love.

Practicing generosity means developing in our mind the intention to give, and it serves to reduce our miserliness—the unwillingness to give that comes from attachment. Each of the seven misdeeds incompatible with far-reaching generosity is relative to one or the other of the three kinds of giving.

Misdeeds Incompatible with Far-reaching Generosity

1. Inconsistent with the giving of material goods.

Chandragomin says, “Not making the three offerings to the Three Jewels.”

When we use Buddhism as a means for our spiritual growth, we put our trust in the Three Jewels—the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha; in other words, we take refuge in them. As followers of the great vehicle within Buddha’s teachings, we also generate the intention to attain Buddhahood for the benefit of all living beings. Having taken refuge and developed bodhicitta, we are advised to honor the Three Jewels by making offerings to them daily. If we neglect to do so, we commit the first secondary misdeed.

When we take refuge in the Three Jewels, it makes sense that if there is something we treasure, that we rely on, that we depend upon, it is a natural human instinct to give gifts, so it makes sense. Being miserly and not giving, you can see how that is counterproductive. Now, although here we’ve also generated bodhicitta and we’re not taking refuge in sentient beings—certainly not—but we’re working for their benefit, it would be contrary to the bodhisattva spirit to not give gifts to sentient beings. But that’s not this particular precept. That one is going to come later. We actually had it in the second root one of not giving the Dharma and material aid to somebody.

According to the analysis of this misdeed found in ‘The Great Way,’ the object of the offerings is any one of the Three Jewels. As explained in the context of the major transgressions, the Buddha Jewel refers to either a living Buddha, like Buddha Shakyamuni or another buddha who is physically present, or to a representation of a buddha such as a statue, painting, photograph, or stupa.

“To Buddha Shakyamuni or some other buddha that’s present”: here the Buddha Jewel includes representations of the statue, thangkas, and so on.

The actual Dharma Jewel is the true cessation of suffering and true paths leading toward this cessation.

The last two of the four noble truths—that’s the actual Dharma Jewel.

Moreover, all the holy texts that contain the Buddha’s words and especially the Mahayana sutras and their commentaries are considered to be the Dharma Jewel.

Actually, they’re representing the Dharma Jewel because those texts and commentaries, and I would also include tapes and videos and things like that in with this, are all showing us how to actualize true paths and true cessations, which are the real Dharma Jewel.

The third object of offerings, the Sangha Jewel, is a minimum of one arya bodhisattva.

So, that’s a bodhisattva who has directly realized emptiness.

Or, in the case of ordinary beings, or non aryas, it is a group of at least four fully ordained monastics, particularly members of the Mahayana Sangha.

So, we have that here now—yay!

As for the nature of the offerings, they may be physical, verbal, or mental.

So, when it says “Not making the three kinds of offerings to the Three Jewels,” we just talked about what the Three Jewels are, and the three kinds of offerings are physical, verbal, and mental offerings.

Physical offerings consist of acts of homage made with our body by doing prostrations.

That’s either the long ones or the short ones.

Or, simply bowing with our hands in prayer position.

So, this means putting our palms together at the heart.

Furthermore, all material substances such as flowers, candles, incense, and so on that we present to the Three Jewels serve as physical offerings.

That’s “physical offerings”—the first one: offerings made by our body. It could be making material offerings on the altar, it could be bowing to the Buddha, it could be just putting our hands together, but it’s some physical something. Unless you’re really, really sick and can’t even move your arms to put them together at your heart. Normally, in the course of a day, hopefully, we make some kind of physical offering.

Verbal offerings are acts of homage presented in the form of a minimum of four lines of praise to the Three Jewels.

It’s four lines of praise: thinking of their qualities and saying something aloud.

Finally, we make offerings mentally by contemplating the Three Jewels’ extraordinary qualities and generating faith in them

This is mentally thinking about them.

This isn’t always so easy to do, is it? Sometimes, even though we’re supposed to make three prostrations in the morning when we get up and before we go to bed, we think, “My back hurts. I’m late. I’m too tired and I forgot.” And we might think, “Somebody else is setting up the altar this morning,” so we don’t do anything.

If we offer our food, that’s something. But maybe I’m on my own. I don’t need to offer my food. Forget it. So, it’s possible that a day goes by without making physical offerings. This is one of the benefits of being in a community: all day long, your whole day is structured so that you’re making offerings.

It’s the same with verbal offerings. It could be easy, and he says a little bit later that we should at least say something that is audible to ourselves. I know sometimes I’m on a plane and can’t start talking. I guess I can go in the bathroom and say the Homage to the Buddha in the bathroom; I usually don’t think of that. I do my practices while I’m on these long plane rides. I do my practices, and I might put my palms together at my heart, but I don’t prostrate down the aisle—although I would like to, and I could use the exercise on these long flights. I think in a situation like that, maybe if you’re verbally saying it to yourself, maybe that’s okay; it doesn’t have to come out of your mouth.

Audience: [Inaudible]

Time is an important element in this misdeed. Neglecting to make offerings to the Three Jewels at least once every 24 hours is a secondary misdeed.

(VTC): I wonder what happens if you’re really, really sick and you sleep, or you’re in a coma for 24 hours. That must be one of these situations when you’re in incredible physical distress.

However, it is not absolutely necessary to present them to all Three Jewels—one is sufficient.

So, just making offerings to one of the Three Jewels is okay.

On the other hand, we must make all three kinds of offerings: physical, verbal, and mental within the 24-hour period. When we have a daily meditation practice, we most likely fulfill this precept, for most practices include praise and moments where we at least join our hands to pay homage. It is at the mental level that we have to be most careful, for when we make a regular habit of reciting our prayers, we may come to say them mechanically and mindlessly. When faith is lacking, recitation of meditation no longer constitutes offerings.

Uh-oh. Let’s get a little bit of faith in here, a little bit of awareness.

There is some discussion as to whether silent meditation is sufficient or if it needs to be accompanied by recitation and physical gestures. After all, it is said that the offerings must be made by means of the body, speech, and mind. It would seem therefore, that a minimum of physical and verbal activity is necessary. We must utter some praise loud enough for us to hear, if not those around us, and at least bow our heads respectfully.

I know when I was training in Nepal, the walls between our rooms were paper-thin, and if you ever did your practices out-loud—wow! Your neighbors really complained because they could hear the whole thing. So, I got in the habit of doing everything silently. That’s my habit. Even if nobody is around, I don’t say it out-loud. Sometimes I think it could be good to say it out loud.

Once bodhisattvas have reached the first of the ten levels, it is no longer possible for them to commit this misdeed for they are making offerings continually.

Isn’t that beautiful? I heard this great story about Rinpoche once. He had cancer and was in the hospital somewhere on the east coast. He was sleeping or in a coma or something, and at one point he woke up and said to his attendant, “There are buddhas all around. Please get something. Let’s make offerings to them.” Isn’t that amazing? His first thought, even though he was in so much physical distress, was seeing all these buddhas. That’s a well-trained mind.

We commit this misdeed, therefore, when we fail to make daily offerings with our body, speech, and mind to any of the Three Jewels. It is more serious if this negligence stems from a lack of respect for the bodhisattva precepts. An example would be the thought, ‘It’s not really important—after all, it’s only a secondary precept.’

That constitutes lack of respect for the bodhisattva precepts.

The transgression may also be prompted by a lack of faith in the Three Jewels.

That’s like thinking, “Three Jewels—yeah, so what?”

Thirdly, laziness in the form of attraction to wrongdoing can induce it.

So, that’s the laziness of being so busy doing other things that we have no time to think about the Three Jewels.

In these cases, the misdeed is said to be associated with afflictions.

You can see, if there’s disrespect, if we’re so attracted to wrongdoings, if we lack faith, there’s affliction in our mind. If we simply forget to make offerings, perhaps because we are very busy, not that we’re attracted to wrongdoing, but maybe you’re working really hard in the temple or something, given that neither lack of respect or lack of faith or laziness in the form of attraction to wrongdoing are involved, the misdeed is said to be disassociated from afflictions.

What’s interesting here is that usually laziness is one of the afflictions, but here if you don’t do something with laziness it’s not considered a transgression associated with afflictions; it’s still considered one without afflictions. It’s not without but not associated with afflictions.

The misdeed is incompatible with one aspect of the bodhisattva ethic of collecting virtue.

When we were talking about the three ethical conducts, this is one that doesn’t go along with the second one, the ethical conduct of collecting virtue, which is to collect merit in relation to superior objects or fields of merit. You can see that not making offerings to the Three Jewels isn’t one of not helping others, and it’s not one of abstaining from negativity. It’s one of not collecting virtue.

So, when you make offerings every morning, or when you bow or anything, you can say, “Oh, I’m fulfilling the first auxiliary bodhisattva precept,” and pat yourself on the back. It’s important that we rejoice in our own merit; it’s important.

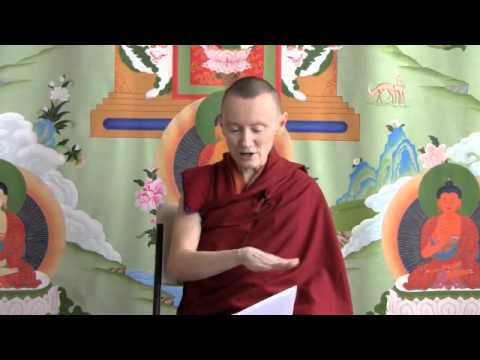

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.